Accediendo al currículo de educación general: Consideraciones para la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidad (Archivado)

Nota: Este recurso ya no se actualizará.

A partir del 16 de mayo de 2025, todos los recursos en español se eliminarán del sitio web debido a la disponibilidad de traductores del navegador web.

Trabaje las secciones de este módulo en el orden en que se presentan en la gráfica de estrella.

Relacionado a este módulo

Derechos de autor 2025 Universidad de Vanderbilt. Todos los derechos reservados.

Reto

Ver el video abajo y después proceda a la sección de Pensamientos iniciales (tiempo: 2:48).

Transcripción: Reto

Principal Flores: As educators, it always seems like we have new issues to deal with, but one thing always remains the same—or should—and that is providing the best education possible for all students. Only, some of our students are in danger of falling through the cracks. Hi there. I’m Yolanda Flores. I’m the principal at Wilbur Valley Middle School. You see, our students with disabilities didn’t perform very well on the standardized tests the past couple of years. In fact, last year we were 4% lower than the previous school year at the Basic level. Only 1 or 2% of students with disabilities scored at the Proficient level, and no one scored at the Advanced levels, even though we’ve made accommodations. Everyone at our school agrees that students with disabilities should be a part of our accountability system. And these students are entitled to accommodations so they can show what they’ve really learned. But it can be so confusing—all these different rules and exceptions! After getting together with my School Improvement Team and hearing what they had to say on the matter, I decided that it was time to sit down with my assistant principal, Jim Ericson, and come up with a plan of action.

Directora Flores: Como educadores, nos parece que siempre tenemos que enfrentar situaciones nuevas, pero siempre hay algo que no varía—o no debería de variar—y eso es proveerles la mejor educación posible a todos los estudiantes. Sólo unos pocos de nuestros estudiantes sienten el peligro de perderse en el sistema educativo. ¡Saludos! Yo soy Yolanda Flores. Soy la directora del colegio Wilbur Valley.

Pues, en los últimos dos años, nuestros estudiantes con discapacidades no han salido bien en las pruebas estandarizadas. De hecho, en el nivel básico los resultados estuvieron 4% por debajo de los que obtuvimos el año pasado. Sólo el 1 ó 2% de nuestros estudiantes con discapacidades logró una puntuación a nivel competente y ninguno alcanzó los niveles avanzados … aunque hemos hecho acomodaciones. Todos en nuestra escuela estamos de acuerdo de que los estudiantes con discapacidades deben pertenecer a nuestro sistema de evaluación. Y estos estudiantes tienen derecho a acomodaciones que les permita demostrar lo que realmente han aprendido. ¡Sin embargo, todo esto puede ser tan confuso! ¡Todos estos reglamentos y excepciones! Después de reunirme con el equipo de trabajo encargado del mejoramiento de la escuela y de escuchar todo lo que tenía que comentar concerniente a este asunto, decidí que ya era hora de reunirme con mi subdirector, Jim Ericson para establecer un plan de acción.

Directora Flores: Jim, creo que lo que tenemos que hacer ahora es concentrarnos en buscar soluciones. Necesitamos crear un plan de acción, uno que pueda aumentar las puntuaciones de los estudiantes.

Señor Ericson: Bueno, podemos comenzar con contratar a más maestros de educación especial.

Directora Flores: ¡Qué más quisiera yo! Los que tenemos están sobrecargados de trabajo. ¿Qué es lo que realmente considera que se necesite para que las puntuaciones aumenten?

Señor Ericson: En este momento, no sé. Hemos incluido a los estudiantes de educación especial en las clases de educación general. Pienso que esto es importante—pero me cuestiono si hemos llevado a cabo el proceso de inclusión de forma eficiente.

Directora Flores: Sabes, es posible que estos estudiantes sepan más de lo que demuestran sus puntuaciones. Creo que debemos reunirnos con los maestros de educación general y con los de educación especial.

Señor Ericson: Buena idea. Nuestros maestros son muy dedicados. Y sé que se han concentrado últimamente en las disciplinas básicas—han dedicado tiempo adicional a la matemática y a la lectura.

Directora Flores: Desafortunadamente, lo que están haciendo no es una buena solución. Será un reto determinar nuestro próximo curso de acción, ¿no crees?

Narrador: La señora Flores y el Señor Ericson están revisando los resultados obtenidos en las evaluaciones de todos los grados con el propósito de entender como las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades pueden mejorar. ¿Qué problemas piensa usted que ellos pudieran descubrir?

¿Cómo pueden la señora Flores y el Señor Ericson utilizar el resumen de los resultados de las evaluaciones de la escuela para concentrar sus esfuerzos en mejorar las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades?

¿Qué preguntas deben hacerles la señora Flores y el Señor Ericson a los maestros de educación general y a los de educación especial?

Pensamientos iniciales

Escriba sus Pensamientos iniciales sobre el Reto:

La señora Flores y el señor Ericson están revisando los resultados obtenidos en las evaluaciones de todos los grados con el propósito de ver como las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades podrían aumentar. ¿Qué problemas piensa usted que ellos pudieran descubrir?

¿Cómo pueden la señora Flores y el señor Ericson utilizar el resumen de los resultados de las evaluaciones de la escuela para concentrar sus esfuerzos en mejorar las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades?

¿Qué preguntas deben hacerles la señora Flores y el señor Ericson a los maestros de educación general y a los de educación especial?

Cuando esté listo, proceda a la sección de Perspectivas y recursos.

Perspectivas y recursos

Objetivo

El participante de este módulo comprenderá que tener acceso al currículo de educación general influye directamente en los resultados de las pruebas para los estudiantes con discapacidades.

Cuando esté listo, proceda a la página 1

Página 1: Un breve repaso

Las evaluaciones de los estados o de los distritos se conocen por el título de “alto riesgo” porque las escuelas, los administradores, los maestros—y a veces los estudiantes—son recompensados o sancionados por su rendimiento en éstas. Existe en la actualidad una fuerte influidez política relacionada con el uso de los resultados de evaluaciones como sistema de asignar responsabilidad a la escuela o al sistema educativo por el rendimiento de los estudiantes en estas pruebas. De acuerdo con las leyes, las Agencias Estatales de Educación deben: incluir a los estudiantes con discapacidades en todas las evaluaciones, con acomodaciones cuando sean apropiadas e informar el nivel de rendimiento de estos estudiantes de la misma manera en que se presentan los informes de los estudiantes sin discapacidades.

Las evaluaciones de los estados o de los distritos se conocen por el título de “alto riesgo” porque las escuelas, los administradores, los maestros—y a veces los estudiantes—son recompensados o sancionados por su rendimiento en éstas. Existe en la actualidad una fuerte influidez política relacionada con el uso de los resultados de evaluaciones como sistema de asignar responsabilidad a la escuela o al sistema educativo por el rendimiento de los estudiantes en estas pruebas. De acuerdo con las leyes, las Agencias Estatales de Educación deben: incluir a los estudiantes con discapacidades en todas las evaluaciones, con acomodaciones cuando sean apropiadas e informar el nivel de rendimiento de estos estudiantes de la misma manera en que se presentan los informes de los estudiantes sin discapacidades.

Para tener en mente

Los estudiantes con discapacidades deben de tener acceso al currículo de Educación General y deben esforzarse por mantener los mismos estándares que otros estudiantes con la ayuda de:

- Asistencia adecuada para la instrucción

- Acomodaciones y modificaciones apropiadas.

Página 2: Entender los datos

Naturalmente, algunos sistemas de datos son capaces de producir datos más útiles que otros sistemas. Los sistemas que son limitados en cuanto a la cantidad de información que contienen (por ejemplo, el tipo de discapacidad) hará el proceso de analizar el éxito de cierta escuela mucho más difícil. Los datos de las evaluaciones deben interpretarse cuidadosamente, y los directores deben recordar a

- Buscar información sobre el sistema de datos utilizado por las oficinas de evaluación a nivel estatal o de distrito.

- Determinar qué información adicional se necesita para entender el rendimiento de los estudiantes.

- Saber qué información se reporta

- Los directores necesitan entender algunos factores clave acerca de los estudiantes con discapacidades que participan en las pruebas de evaluación, incluyendo:

- Qué acomodaciones se están utilizando

- El número de estudiantes que utilizan evaluaciones alternativas

- Qué puntuaciones no se incluyen en el índice de mejoramiento de la escuela. (Unos distritos no incluyen puntuaciones de pruebas administradas con acomodaciones o las de evaluaciones alternativas en sus informes de datos.)

Para tener en mente

Si la información necesaria ha sido obtenida pero no informada, los directores deben solicitar esos datos adicionales en las oficinas de evaluación estatal o de distrito. Si la información necesaria no se ha recopilado, es común que los directores implementen procedimientos para procurar información para su propia escuela.

Página 3: Una primera vista de los datos

Primero:

- Busque los resultados esperados.

- Busque los resultados inesperados.

- Examine los errores cometidos por un grupo considerable de estudiantes.

Segundo:

- Reconozca que la mayoría de los estados y los distritos informan solamente dos de los elementos requeridos por la ley.

- Identifique el número de estudiantes con discapacidades que tomaron las pruebas estandarizadas.

- Examine las puntuaciones obtenidas por los estudiantes con discapacidades.

Tercero:

- Busque otra información más a fondo como:

- Los porcentajes de estudiantes con categorías distintas de discapacidades; y/o

- El número de estudiantes que reciben acomodaciones, por categoría de discapacidad.

Página 4: Comparar los datos

Una parte importante de interpretar los datos es determinar la eficacia relativa de los esfuerzos del mejoramiento de la escuela al comparar los resultados. Una escuela que intenta elevar los resultados en matemáticas entre los estudiantes con discapacidades descubrirá que hay varios métodos de comparar esos resultados al nivel básico de rendimiento.

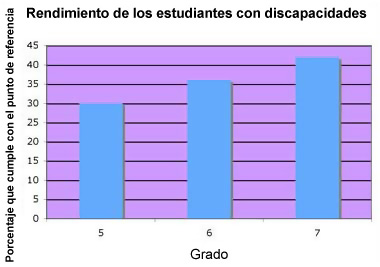

Varios grados en un solo año

Varios grados en un solo año

Puede que un director de escuela quiera medir qué porcentaje de estudiantes con discapacidades de cada nivel de grado tiene un rendimiento que corresponde con el punto de referencia. En la gráfica que se encuentra a la derecha, 30% de los estudiantes del quinto grado, 36% de los estudiantes del sexto grado y 42% de los estudiantes del séptimo grado están cumpliendo con el punto de referencia.

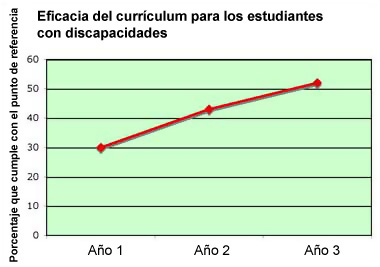

Sólo un grado a través de varios años

Sólo un grado a través de varios años

Puede que un director de escuela quiera determinar si un currículum del sexto grado que recién se adoptó es eficaz. En la gráfica que se encuentra a la izquierda, 30% de los estudiantes del sexto grado cumplió con el punto de referencia para el Año 1, 43% para el Año 2 y 52% para el Año 3.

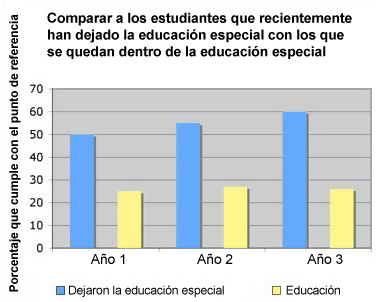

Múltiples grupos en múltiples años

Múltiples grupos en múltiples años

Puede que un director de escuela quiera comparar a los estudiantes que han dejado la educación especial dentro del último año escolar con los estudiantes que continúan recibiendo los servicios de la educación especial. El gráfico que se encuentra a la derecha ilustra que, durante tres años, los estudiantes que han dejado la educación especial tienen resultados más altos que los que se han quedado dentro de la educación especial.

Actividad

Recopile los datos de una evaluación reciente de un distrito que no sea el de usted. (Esta información debe estar disponible en Internet.)

- Observe el informe de las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades. ¿Qué datos son informados? ¿Qué porcentaje de estudiantes con discapacidades en el distrito está a un nivel aceptable de rendimiento?

- Ahora observe los datos de la misma evaluación en el distrito de usted. De los estudiantes con discapacidades, ¿qué datos fueron informados? ¿Qué porcentaje de estudiantes con discapacidades en su distrito está a un nivel aceptable de rendimiento?

- Ahora compare los dos distritos. ¿Es diferente el método para informar los datos de los estudiantes con discapacidades? ¿Le parece a usted un método mejor que el otro? Si es así, ¿por qué?

Página 5: Entender los desafíos al comparar los datos

Es crucial para los directores saber de qué datos se informan y entender los datos que están interpretando. Puesto que las leyes estatales requieran que los estados y distritos informen del número de estudiantes que se evalúan pero no les requiere informar de los números de matrícula, a menudo es imposible determinar si todos o algunos de los estudiantes con discapacidades participaron en las pruebas. Es común para los estados:

- No diferenciar claramente los resultados de los estudiantes con discapacidades

- No diferenciar los resultados de los estudiantes que dan la prueba de los resultados de los estudiantes que dan una evaluación alternativa

- Agregar – o incluir – los resultados de pruebas dadas con acomodaciones “no aprobadas” con los resultados de la prueba estándar

- No informar de los resultados de pruebas dadas con acomodaciones no estándar y no indicar que no están informando de ellos

Hay que tener cuidado al interpretar los datos de grupos. Cuando los estudiantes con el rendimiento más alto de la educación especial van a la educación general y los estudiantes con el rendimiento más bajo de la educación general van a la educación especial, el rendimiento de los estudiantes de la educación especial parece no mejorar a través del tiempo. Es importante seguir la movilidad hacia la educación especial y alejándose de ella y mirar los datos de varias maneras.

Escuche ahora mientras Victor Nolet explica el reto de la interpretación de los datos de un grupo pequeño de estudiantes (tiempo: 1:07).

Victor Nolet, Ph.D.,

Profesor Asociado

Departamento de Educación Especial

Universidad de Western Washington

Transcripción: Victor Nolet, Ph.D.

Una de las cosas por las cuales usted debe preocuparse al tomar decisiones es el efecto de tener pocos estudiantes en el grupo, un cambio pequeño puede hacer una gran diferencia. Y si un director de escuela está pensando en el rendimiento de los estudiantes con discapacidades en sus evaluaciones a gran escala, puede observar el rendimiento de un grupo de estudiantes y pensar, bueno, nuestro rendimiento no parece ser tan bueno este año como el del año pasado. ¿Estamos progresando como escuela? ¿O estamos progresando como programa? Cuando nada más de media docena o una docena de estudiantes comprimen un grupo, puede haber sólo diez o quince estudiantes con discapacidades en su evaluación a gran escala. Cualquiera de estos estudiantes podría mejorar grandemente o no mejorar nada este año. Un estudiante podría unirse al grupo, otro mudarse, y entonces tendríamos un cambio grande en nuestros datos a causa de lo que nosotros llamamos un tamaño-n pequeño. Por eso siempre nos preocupamos por examinar los efectos de nuestros programas, particularmente en lo que se refiere a los estudiantes con discapacidades, en esos grupos pequeños.

El problema de interpretar los datos de un grupo pequeño de estudiantes puede ser algo aliviado al llevar a cabo evaluaciones adicionales, incluyendo a métodos relacionados al contexto como portafolios de los trabajos de estudiantes o pruebas de progreso a través del año.

Página 6: Realizar mejoras

Después de interpretar los datos, los directores deben formar equipos de trabajo compuestos de maestros de varias disciplinas para ayudar a desarrollar estrategias para el mejoramiento de las puntuaciones.

Los planes de mejoramiento deben utilizar los datos aislados al rendimiento de los exámenes—separados por grupos—para trabajar con las necesidades específicas de los estudiantes con discapacidades.

Los planes de mejoramiento deben utilizar los datos aislados al rendimiento de los exámenes—separados por grupos—para trabajar con las necesidades específicas de los estudiantes con discapacidades.- Los planes de mejoramiento no deben incluir medidas que puedan afectar negativamente la instrucción de los estudiantes, como limitar el currículo, los repasos, los ejercicios de práctica u otro enfoque a corto plazo, con el fin de mejorar el aprendizaje de los estudiantes a largo plazo.

- Recuerde que el director de escuela es un modelo de la instrucción, el currículo y la evaluación para la escuela. Las actitudes y las creencias del director afectarán la evaluación y la instrucción de toda la escuela. Usted debe mantener una actitud positiva; enfocarse en lo que los estudiantes necesiten para tener éxito; y entender que los cambios requieren tiempo para realizarse.

Actividad

Recopile datos del estado y del distrito de los pasados últimos años de dos de los distritos escolares locales. En muchas ocasiones, los periódicos locales proveen esta información. Compare el rendimiento de los estudiantes con discapacidades en dos niveles de grado de un distrito de alto rendimiento con el rendimiento de estudiantes de educación general en niveles de grado comparables de un distrito de un rendimiento menor. Escriba una descripción que indique como los estudiantes de educación especial comparan con los estudiantes de educación general. Usted podría discutir las tendencias de distintos grupos de edad a través de los años.

Página 7: ¿Qué se está enseñando?

Escuche mientras Margaret McLaughlin explica la importancia de mantener los mismos estándares altos de funcionamiento para estudiantes con discapacidades cognitivas que existen para todos los demás estudiantes (tiempo: 2:47).

Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Profesora, Departamento de Educación Especial

Universidad de Maryland, College Park

Transcripción: Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Una de las primeras suposiciones en las que se basa el requisito de que los estudiantes con discapacidades tengan acceso al currículo de educación general es la que indica que el currículo de educación general esté en armonía con los estándares de materia y contenido—es la noción de que los estudiantes con discapacidades tienen el derecho y deben de tener la oportunidad de tener acceso a estos estándares. Y, particularmente, porque ahora consideramos que los estándares de contenido son los que representan—o hacen más explícitas—las enseñanzas y las destrezas esenciales y duraderas que deseamos que todos los estudiantes aprendan—y todos los estudiantes también quiere decir los estudiantes con discapacidades. Entonces nosotros pensamos que es muy importante que los estudiantes con discapacidades tengan acceso a los estándares, y la forma en que ellos deben hacer esto es a través de un currículo que esté en armonía con esos estándares.

Es muy importante tanto para las necesidades de estos niños como para la equidad social, que si alguien—el estado, por ejemplo, o el distrito local—ha determinado que ese contenido es información importante que los estudiantes deben de aprender, que sea igual de importante que los estudiantes con discapacidades aprendan ese mismo material. Sin embargo, un concepto erróneo que muchos comparten, cuando se comienza a hablar de los estándares del contenido educativo o del currículo de educación general, es que los estudiantes con discapacidades nunca serán capaces de aprender ese material: es demasiado difícil cognitivamente; requiere demasiadas destrezas; es demasiado complejo. Y de muchas maneras esto representa un concepto erróneo o evidencia poco conocimiento del currículo y también demuestra una falta de conocimiento de la historia de la educación especial en la enseñanza de individuos con discapacidades.

Yo sólo les solicito a las personas que piensen en los ejemplos más clásicos de nuestra historia. Y hace nada más de unas cuantas décadas que pensábamos que los individuos que padecían del síndrome de Down eran incapaces de ser educados. Los internaban en instituciones; no les ofrecían ningún tipo específico de educación. Ahora sabemos por nuestras propias vidas y experiencias diarias que estos individuos no sólo aprenden, sino que aprenden muy bien. Se gradúan de la escuela secundaria, tienen una variedad de destrezas literarias, tienen empleos, viven independiente en la comunidad. Y esto no simplemente sucedió, esto sucedió a través de la educación. Ahora, para que nosotros logremos en realidad estos estándares altos y expectativas altas para los estudiantes con discapacidades, debemos hacer una revisión de lo que es el currículo de educación general y cómo repensarlo para los estudiantes con discapacidades.

Créditos

Fotografías

- La corporación de New Horizons:

- Foto de una joven organizando cuadernos en un cajón

- Foto de un empleado poniendo inserciones en un libro

- Foto de un joven marcando las horas de trabajo

- Foto de un empleado haciendo cajas

- Foto de un grupo de pie en frente de una camioneta

Para tener en mente

Los maestros deben considerar el nivel de complicación del material que enseñan. ¿Se basa esencialmente en hechos y conceptos o en principios y procedimientos? El tipo de pensamiento que los estudiantes realizan es influido en gran manera por la variedad de información que aprenden. Información más complicada, como se manifiesta en la enseñanza de los principios y los procedimientos, resulta en procesos cognitivos de un nivel más alto.

Página 8: Base legal

En 1997 se hicieron cambios importantes a IDEA (Ley de la Educación de Individuales con Discapacidades) de manera que la práctica de la educación especial se incluyera en una reforma basada en estándares. Para especificar como un estudiante tendría acceso al currículo de educación general, el PEI (Plan Educativo Individualizado) debe ahora incluir:

- Una declaración sobre los niveles de rendimiento educativo del estudiante al presente, incluyendo información sobre como la discapacidad del estudiante afecta su grado de inclusión en el currículo general

- Metas anuales medibles, incluyendo objetivos a corto plazo, encaminados a cubrir las necesidades del estudiante

- Descripciones de las modificaciones o la asistencia que el estudiante necesitará para:

- Progresar hacia obtener las metas anuales

- Progresar en el currículo general

- Participar en eventos extracurriculares u otras actividades no académicas

- Participar en actividades con otros estudiantes con o sin discapacidades

Estos requisitos se aplican a todos los estudiantes con discapacidades, independiente de su ambiente educativo.

Para su información

En el pasado, los estudiantes con discapacidades eran distanciados de la educación general. Las evaluaciones para estos estudiantes medían deficiencias en destrezas discretas e imediatas. Los PEI eran una colección de objetivos de destrezas aisladas que entonces conducían a una instrucción aislada. El PEI se convertía a menudo en el currículo para el estudiante, en lugar de una herramienta para definir como poner en práctica el currículo de educación general. El mandato de 1997 de armonizar el PEI con el currículo y los estándares de la educación general propone una manera enteramente nueva de pensar sobre la educación especial.

Página 9: Utilizando el currículo

|

|||||||||

| (Nolet & McLaughlin, 2000) |

Página 10: Requisitos legales

Recuerde que la Ley establece que:

Los individuos con discapacidades deben de ser incluidos en programas de evaluación con acomodaciones, según sus necesidades.

Los individuos con discapacidades deben de ser incluidos en programas de evaluación con acomodaciones, según sus necesidades.- Los estados y los distritos escolares deben establecer pautas para las evaluaciones alternativas de los estudiantes con discapacidades que no puedan participar en las evaluaciones generales. Presione aquí para ver la política estatal de acomodaciones para los estudiantes con discapacidades.

- El rendimiento de los estudiantes con discapacidades en las evaluaciones debe de ser informado conjuntamente con el de sus pares.

Página 11: Acomodaciones

Una acomodación es un servicio o respaldo que provee asistencia al estudiante para que tenga acceso de forma completa a la materia de estudio y a la instrucción, y para que demuestre de forma completa lo que él o ella sabe relacionado a la discapacidad del niño a través de todo el currículo de educación general. Por ejemplo, para un estudiante con una discapacidad en lectura, los maestros deben de proveerle al estudiante una acomodación que envuelva todas las áreas de contenido (ej., matemáticas, ciencias) que requieren lectura de manera que el contenido no le resulte desconocido en el día del examen. Una acomodación no es:

Una acomodación es un servicio o respaldo que provee asistencia al estudiante para que tenga acceso de forma completa a la materia de estudio y a la instrucción, y para que demuestre de forma completa lo que él o ella sabe relacionado a la discapacidad del niño a través de todo el currículo de educación general. Por ejemplo, para un estudiante con una discapacidad en lectura, los maestros deben de proveerle al estudiante una acomodación que envuelva todas las áreas de contenido (ej., matemáticas, ciencias) que requieren lectura de manera que el contenido no le resulte desconocido en el día del examen. Una acomodación no es:

- Un cambio en el contenido de instrucción o en las expectativas que se tienen para el rendimiento de los estudiantes

- Una interrupción o un cambio significativo en los estándares especificados para los estudiantes

- Una alteración a la visión global o los resultados educativos principales que se esperan de la enseñanza

Hay muchas instancias en las cuales los estudiantes se beneficiarían de las acomodaciones. Estas incluyen a:

- Los estudiantes con deficiencias motoras, sensoriales o de procesamiento de información se benefician de herramientas alternativas de adquisición, tales como los intérpretes de lenguaje de señas, materiales en Braille y grabaciones de libros

- Los estudiantes con problemas de aprendizaje pueden ser ayudados por contenidos enriquecidos tales como organizadores de antemano, diagramas, guías de estudio, aparatos mnemotécnicos o enseñanza mediada por los pares

- Los estudiantes que tienen problemas con expresarse a causa de deficiencias motoras o sensoriales o diferencias en el lenguaje, pueden beneficiarse de un escribano o de recibir tiempo adicional para completar sus trabajos

Es de beneficio para los maestros usar una lista de control (ej. Lista de control para la evaluación de acomodaciones (PDF) para ayudarle a desarrollar las acomodaciones necesarias para los estudiantes que requieran este tipo de intervención. Las acomodaciones pueden incluir asistencia con las instrucciones de los exámenes, la programación, los formatos de los examenes y otras sugerencias mostradas en las tablas que siguen a continuación.

| Ejemplos de acomodaciones instructivas | ||

| Agarres especiales para lápices | Tiempo adicional para completar asignaciones o exámenes | Práctica adicional en destrezas específicas o conceptos |

| Libros con letra grande | Calculadoras y correctores ortográficos | Más oportunidades para aplicar destrezas o conceptos |

| Un ambiente más silencioso | Software del procesamiento de textos | Instrucción directa para utilizar conocimiento específico en una variedad de contextos |

En adición a las acomodaciones para la enseñanza, existen muchos tipos de acomodaciones para los exámenes (Centro nacional de los resultados educativos, sin fecha). Lo ideal sería que primero los estudiantes se familiarizaran con las acomodaciones durante la enseñanza.

| Ejemplos de acomodaciones para los exámenes | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| Localización | Tiempo | Programación | Presentación | Respuesta |

| Cambie el lugar de examen. Por ejemplo, permita al estudiante tomar el examen con un grupo pequeño de estudiantes o individualmente. | Permita tiempo adicional o descansos frecuentes. | Permita tomar los exámenes durante varios días o adminístrelos solamente en un horario específico. | Cambie el formato del examen utilizando aparatos de asistencia, tales como lectores personales o computadoras | Cambie la manera en que el estudiante conteste, tal como permitirle utilizar un escribano, una grabadora o una computadora. |

Escuche ahora mientras Margaret McLaughlin discute las acomodaciones para los exámenes y proporciona varios ejemplos de estudiantes que podrían utilizar las acomodaciones para los exámenes.

Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Profesora, Departamento de la Educación Especial

Universidad de Maryland, College Park

Transcripción: Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D. – Acomodaciones para los exámenes

Hay muchos aspectos principales, básicamente, que los directores, e inclusive los maestros y los padres, deben de saber acerca de las evaluaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades. Una de las áreas más discutidas son las acomodaciones para los exámenes. Y claro, los estudiantes con discapacidades tienen derecho a una acomodación al momento de una prueba, en cualquier tipo de evaluación en realidad. Y este tipo de acomodación ha causado muchos malentendidos, y hay mucha confusión, creo, en cuanto a qué acomodaciones se permiten, qué no se considera una acomodación, y si debiéramos de ofrecerle una acomodación a cualquier estudiante con una discapacidad, etc. Una acomodación, o una acomodación para la evaluación, puede ser muchas cosas. Quiero decir que puede ser tan sencillo como extender el tiempo que se le proporciona a un estudiante para completar una sección de la evaluación, pero también pueden existir acomodaciónes más complejas. Por ejemplo, se puede utilizar la asistencia de tecnología, o tener un escribano u otro individuo que ayude al estudiante. Sin embargo, al momento en que pronuncio la palabra “ayuda”, quiero destacar la importancia de reconocer que una acomodación no está diseñada para que el estudiante rinda mayores resultados, está diseñada para contrarrestar el impacto que pueda tener la discapacidad sobre el estudiante. En otras palabras, la interpretación legal de una acomodación es que debe ofrecerles a todos los estudiantes la misma oportunidad de lograr éxito. Ahora, ya sabemos algo del impacto de las acomodaciones en los resultados de los exámenes, pero nada todavía en absoluto. Las acomodaciones pueden tener un efecto diferente para cada estudiante, dependiendo de su discapacidad, dependiendo de lo que se requiere en una evaluación en particular. Así que, una acomodación debe de ser diseñada, seleccionada y utilizada durante una evaluación con mucho cuidado, con consideración de las necesidades educativas particulares del estudiante, y ciertamente la acomodación debe de aplicarse durante la instrucción en la clase también. Y también requiere la supervisión.

Transcripción: Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D., PhD – Ejemplos de acomodaciones para los exámenes

Vamos a tomar un ejemplo sencillo. Un estudiante que tiene un impedimento visual obviamente necesitará algún tipo de acomodación para poder leer el material en un examen a lápiz y papel. Sin embargo, si ese estudiante tiene un impedimento auditivo, no sería particularmente beneficioso e inclusive podría perjudicar el rendimiento del estudiante darle un examen con letra grande, o ciertamente una versión en Braille, porque es obvio que esto no es algo que el estudiante utiliza durante la enseñanza, y no le serviría de ayuda. Entonces, necesitamos pensar en todas las acomodaciones, aunque sean los ejemplos anteriores bastante obvios, debemos de tener en mente los principios que exponen. También necesitamos considerar las acomodaciones por sub-pruebas o las exigencias de los exámenes, las exigencias de las evaluaciones. Obviamente, en el caso de exámenes tales como los de comprensión de lectura, o de lectura en general, si usted utiliza un lector, alguien que le lea el examen al estudiante, esta evaluación será inútil. Ese resultado será un resultado no estándar porque la acomodación en realidad comprometió la validez de la información obtenida por ese medio. No se aprende nada sobre la capacidad del estudiante de leer. Se aprende lo bien que el estudiante puede escuchar a un lector y responder a ciertas preguntas. Así que estas decisiones no se pueden tomar ligera o aisladamente. Requiere que el equipo del PEI entienda bastante sobre la evaluación y sobre qué tipo de decisiones e inferencias se debe esperar de estos resultados de esa evaluación, y desde luego, deben de conocer al estudiante.

Página 12: Modificaciones

Una modificación es:

- Un cambio en la enseñanza o el currículo de un estudiante en el que el contenido de la instrucción o la expectativa del rendimiento están alterados.

¿Por que se utilizan las modificaciones?

Deficiencias en las destrezas de lectura o de matemática pueden hacer que los estudiantes encuentren dificultades en alcanzar las metas del currículo para todos los otros estudiantes. Unas modificaciones bien preparadas pueden ayudar al estudiante con este tipo de déficit en destrezas a progresar en un currículo general de acuerdo con su nivel.

¿Quiénes utilizan las modificaciones?

Las modificaciones ayudan a aquellos estudiantes que han sido considerados para todos los tipos de acomodaciones posibles y aún requieren que se tomen medidas adicionales para ayudarlos a progresar en un currículo de educación general.

Ejemplos de modificaciones

| Reducir las asignaciones | Asigne menos problemas o requiera que el estudiante escriba uno o dos párrafos en lugar de varias páginas. |

| Variar los niveles del material de lectura | Los estudiantes en una clase pueden leer literatura de diferentes niveles, mientras todos aprenden a identificar el desarrollo de los personajes, la trama y “la voz”. |

| Diseñar nuevos materiales | La tareas pueden reflejar el currículo de educación general, pero variar en dificultad. Por ejemplo, todos los estudiantes pueden recibir la enseñanza de matemáticas, pero algunos pueden estudiar el algebra básico, mientras que otros resuelven problemas de palabras sencillos. |

| Utilizar exámenes de niveles más bajos | Utilice un libro de texto, o un examen que, aún cuando es de la misma materia, es de un grado menor al de la clase. |

Precauciones al utilizar las modificaciones

- Pueden afectar el nivel del currículo, eliminando tareas difíciles y alterando lo que los estudiantes deben de aprender.

- Pueden limitar las oportunidades del estudiante de obtener conocimientos esenciales, las destrezas y los conceptos de una materia específica.

- Materia de grados menores puede interrumpir la secuencia estratégica del currículo, que últimamente puede causar mayores deficiencias relacionadas con conocimiento anterior que las que podrían habérsele creado por el déficit del aprendizaje original.

- Puede poner al estudiante en desventaja en las evaluaciones que puede resultar en consecuencias significativas tanto para los estudiantes como para las escuelas.

Página 13: Evaluaciones alternativas

Una evaluación alternativa es:

Como usted aprendió anteriormente, para los estudiantes con discapacidades que no pueden participar en las evaluaciones del estado o de los distritos, el estado y los distritos locales tienen que desarrollar unas guías para la participación de ellos en evaluaciones alternativas; además, deben de informar el rendimiento de estos estudiantes conjuntamente con el de sus compañeros que no tienen discapacidades. Las agencias de educación de los estados tienen una variedad de políticas relacionadas con definir las evaluaciones alternativas y con determinar qué estudiantes deben de ser evaluados.

¿Por qué se utilizan las evaluaciones alternativas?

El rendimiento y el progreso de cada estudiante tienen que ser informados, y las evaluaciones alternativas proveen los medios para evaluar el aprendizaje de aquellos estudiantes que no pueden participar en las evaluaciones generales.

¿Quiénes utilizan las evaluaciones alternativas?

En general, los administradores federales y estatales concurren en que sólo los estudiantes con mayores dificultades cognitivas deben usar las evaluaciones alternativas, alrededor del 1–2% de todos los estudiantes. Estos estudiantes generalmente tienen un currículo más orientado a desarrollar las destrezas de vida. Usted tendrá que contactar su administrador de educación especial de su distrito local y/o con el departamento estatal de educación para determinar cuáles son las evaluaciones alternativas que se están utilizando. (Nolet & McLaughlin, 2000)

Ejemplos de evaluaciones alternativas

El Departamento de Educación de Iowa ha desarrollado una evaluación alternativa para los estudiantes con discapacidades. Esta evaluación alternativa está basada principalmente en los trabajos de los estudiantes que han sido recopilados por los maestros, tales como:

|

|

Escuche ahora mientras Margaret McLaughlin informa de la efectividad de los esfuerzos recientes para lograr una reforma basada en estándares; se enfoca particularmente en la eficacia con que se les provee assistencia a los estudiantes con discapacidades para que logren éxitos académicos más altos (tiempo: 1:25).

Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Profesora, Departamento de la Educación Especial

Universidad de Maryland, College Park

Transcripción: Margaret J. McLaughlin, Ph.D.

Una evaluación alternativa, como se ha empleado en IDEA y de acuerdo con otras leyes, se refiere a cualquier evaluación que no sea la evaluación estándar que ha sido diseñada o que se ha diseminado o administrado a la población general. Y típicamente una de estas evaluaciones se concibe de muchas otras maneras. Puede ser un portafolio; puede ser algún tipo de examen de respuesta múltiple; puede ser una combinación de tareas de evaluación—un portafolio del trabajo de un estudiante y otra forma de evaluación más tradicional—pero típicamente se consideran, o por lo menos en referencia a estos asuntos, aplicables sólo a un porcentaje o una proporción mínima de estudiantes con discapacidades, usualmente a los que presenten las discapacidades cognitivas más severas. Y, en esta función, la evaluación alternativa típicamente se establece en base de otros estándares, algunas personas dirían estándares más funcionales, orientados a destrezas de la vida, tal vez vocacional, de una ocupación. Pero no es el mismo conocimiento o contenido educativo que se están midiendo las evaluaciones del estado o del distrito.

Actividad

Determine el porcentaje de estudiantes con discapacidades en su estado que participaron en evaluaciones alternativas el año pasado.

Página 14: Resumen

A pesar de que la cantidad de cambios que se pueden hacer a la enseñanza y a las evaluaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades puede causar confusión, es beneficioso pensar en estos cambios como un continuo:

- Es claro que para algunos estudiantes, como los que reciben servicios de lenguaje y del habla exclusivamente, es posible que cambios al contenido o a la enseñanza del currículo general no sean necesarios:

- Para otros estudiantes, se hacen acomodaciones para la enseñanza, pero se espera que el estudiante aprenda todo el contenido del currículo al igual que sus compañeros de la clase.

- Cuando se aumentan en su intensidad, las modificaciones del currículo empiezan a cambiar las expectativas relacionadas al contenido así como los logros y los resultados del aprendizaje del estudiante.

- Finalmente, para algunos estudiantes, una serie de metas totalmente individuales se debe definir. Estos estudiantes generalmente no participan en las evaluaciones generales sino que se les proporciona evaluaciones alternativas.

Aunque usted acaba de aprender que los cambios en la enseñanza y en los exámenes son esenciales para la educación de los estudiantes con discapacidades, no es poco común que otros estudiantes o padres se quejen de que estos cambios les parecen injustos.

Escuche ahora mientras Virginia Richardson describe como ella responde cuando escucha quejas de que las acomodaciones y las modificaciones recibidas por estudiantes con discapacidades sean “injustas” (tiempo: 1:29).

Virginia Richardson

El Centro PACER (Coalición de Padres por los Derechos Educativos)

Directora de la Capacitación de Padres

Minneapolis, MN

Transcripción: Virginia Richardson

Creo con certeza que es un problema para los niños que no parecen tener una discapacidad. Si vemos a un niño en una silla de ruedas, de ninguna manera esperamos que este individuo se levante para caminar en el salón de clases. ¿Comprendes? A veces los niños vienen con discapacidades—requiriendo que ellos se sienten tranquilos por una hora para completar un examen es una expectativa tan irreal como la del niño en la silla de ruedas. Y siempre les explico a los padres que las acomodaciones para las evaluaciones no se emplean para darles a estos estudiantes una ventaja injusta, sino que se dan para contrarrestar los efectos de la discapacidad, porque los niños son todos diferentes. Y los niños en la educación especial han sido examinados para determinar cuales son sus necesidades, y no son conclusiones ligeras, tienen problemas reales. Y me digo, ninguno de estos niños continuarán para obtener títulos universitarios—tengo una niña con retardación mental, entonces puedo usar este ejemplo—no pueden ser estudiantes en la universidad o hacer todas las cosas de una vida típica. Las personas sin discapacidades no cambiarían lugares con estos niños, como Debbie, para recibir las acomodaciones que hacen la vida un poco más justa. Ellos no considerarían la vida justa si estuvieran en el lugar de ella…

La siguiente tabla define un continuo de cambios que se puede realizar en la enseñanza y la evaluación de los estudiantes con discapacidades:

| Sin acomodaciones o modificaciones | Acomodaciones | Modificaciones | Evaluaciones alternativas |

|

Individualizar toda la enseñanza (metas y objetivos del PEI)

Enseñanza dentro de la educación general

Participación completa en evaluaciones del estado/distrito |

Enumerar los estándares y las acomodaciones especiales

Enseñanza con acomodaciones en la educación general

Enseñanza en destrezas individualizadas (metas y objetivos del PEI)

Participación en evaluaciones del estado/distrito con acomodaciones |

Metas del currículo diferentes o modificadas

Describir los servicios y las ayudas complementarias

Enseñanza individualizada de destrezas

Documentar las razones por las evaluaciones alternativas

Participación en evaluaciones del estado/distrito y/o evaluaciones alternativas |

Diseñar instrucción individualizada

Documentar de forma convincente las razones por exenciones de las evaluaciones del estado/distrito

Describir las evaluaciones alternativas |

(Nolet & McLaughlin, 2000)

Página 15: Referencias

Para citar este módulo, favor de usar el siguiente formato:

The IRIS Center. (2004). Accediendo al currículo de

educación general: Consideraciones para la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidades. Accedido de https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/agc_spanish/

Recursos del módulo (en inglés) Información sobre recursos adicionales (en inglés)

Libros

National Center on Educational Outcomes. (n.d.). Accommodations for Students

with Disabilities. Accedido el 10 de mayo, 2004, de http://www.cehd.umn.edu/NCEO/TopicAreas/Accommodations/Accomtopic.htm

Iowa Department of Education. (2004) Children, family, and community services.

Accedido el 28 de enero, 2008, de http://www.iowaccess.org/educate/ecese/cfcs/index.html Ya no está disponible.

Nolet, V., & McLaughlin, M.J. (2000). Accessing the general curriculum.

Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Thurlow, M. (2001). Students with disabilities in standards-based reform.

Framing paper for The National Summit on the Shared Implementation of IDEA.

Thurlow, M. L., Elliott, J. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E. (2003). Testing students with

disabilities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Use multiple measures to assess students with disabilities. (2004, febrero).

Inclusive Education Programs, 11 (2), págs. 1, 8.

McLaughlin, M. J. & Nolet, V. (2004). What every principal needs to know

about special education. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc.

Thompson, S. J., Quenemoen, R. F., Thurlow, M. L., & Ysseldyke, J. E.

(2001). Alternate assessments for students with disabilities. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press, Inc. and Council for Exceptional Children.

Página 16: Créditos

Para citar este módulo, favor de usar el siguiente formato:

The IRIS Center. (2004). Accediendo al currículo de

educación general: Consideraciones para la inclusión de estudiantes con discapacidades. Accedido de https://iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu/module/agc_spanish/

Expertos de Contenido:

Margaret McLaughlin

Victor Nolet

Desarrolladores del Módulo:

Zina Yzquierdo

Alicia Stark

Equipo de Producción del Módulo:

Editor:

Jason Miller

Revisores:

Janice Brown

Susan Flippin

Jason Phelan

Kim Skow

Deb Smith

Naomi Tyler

Debbie Whelan

Traductores:

Anna-Lisa Halling

David Wiseman

Equipo de Apoyo a la Producción del Módulo:

Permisos:

Susan Flippin

Kim Skow

Transcripciones:

Pamela Dismuke

Equipo de Producción de los Medios de Comunicación:

Ingeniero de audio:

Tim Altman

Especialista de los medios de comunicación/apoyo técnico:

Erik Dunton

Administrador de web:

John Harwood

Transcripciones:

Pamela Dismuke

Narraciones:

Little Planet (Reto)

Tim Altman (Reto, Resumen)

Técnico de audio:

Tim Altman

Gráficas:

Clipart

Fotografías:

Little Planet Learning

Microsoft Clipart

“Victor Nolet” por atención de the IRIS Center

Carolyn Stalcup

iStockPhoto

New Horizon

“Margaret McLaughlin” por atención de the IRIS Center

ReelVision Media

“Virginia Richardson” por atención de the Pacer Center

Entrevistas con Expertos:

Victor Nolet (págs. 5, Resumen)

Margaret McLaughlin (págs. 7, 11, 13, Resumen)

Virginia Richardson (pág. 14)

Resumen

En este módulo usted ha aprendido acerca de algunos asuntos complicados y ahora está preparado para enfrentar el reto de ayudar a los estudiantes con discapacidades a obtener un rendimiento a nivel alto en las evaluaciones del estado y del distrito. Presione el enlace que aparece abajo para escuchar un resumen de lo que ha aprendido en este módulo. Escuchará nuevamente las voces de los Drs. Margaret McLaughlin y Victor Nolet mientras ellos resaltan algunos de los puntos clave del módulo (tiempo: 4:14).

Transcripción: Resumen

Narrador: Ahora que usted ha completado el módulo, está preparado/a para comenzar la tarea de mejorar las puntuaciones de las evaluaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades. Pero antes de comenzar, debemos repasar rápidamente lo que ha aprendido en este módulo. Primero, es extremadamente importante saber qué datos se incluyen en los informes de evaluación del estado o del distrito. También es útil solicitar o recopilar datos adicionales para obtener una idea clara del aprendizaje que se realiza en una escuela.

Dr. Nolet: Los directores y los equipos de las escuelas necesitan verse a si mismos como detectives que recopilarán evidencia para tratar de tomar algunas decisiones. Y siempre estamos interesados en la validez de esas decisiones. ¿Habremos recopilado la evidencia correcta? ¿Habremos recopilado una cantidad suficiente de evidencia? ¿Y habremos tomado las decisiones apropiadas con respeto a la evidencia recopilada?

Narrador: También ha aprendido a examinar los datos cuidadosamente, considerando grupos específicos, inclusive grupos de estudiantes con discapacidades. Para que los estudiantes con discapacidades rindan bien en las evaluaciones de alto riesgo, es importante que tengan acceso al currículo de educación general. Para trabajar hacia el mejoramiento de la enseñanza y la evaluación dentro de la escuela, los directores deben formar equipos de maestros para desarrollar y implementar estos planes de mejoramiento.

Dr. McLaughlin: Debe de ser obvio que esto no es algo que los maestros de educación especial pueden realizar solos. Éste no es un asunto de la educación especial; es un asunto que afecta toda la escuela. Cuando comenzamos a discutir sobre proveer acceso al currículo de educación general, tenemos que también hablar de cómo los maestros de educación general y los de educación especial pueden trabajar juntos para encontrar nuevas formas de ayudarles a todos los estudiantes a aprender esta información tan importante.

Narrador: Hay varios asuntos clave relacionados con el mejoramiento de los resultados de las evaluaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades. Los estudiantes tienen mayor acceso al currículo de educación general cuando el currículo propuesto, el que se enseña y el que se aprende están íntimamente alineados.

Dr. Nolet: Los maestros necesitan conocer a fondo los estándares porque su comprensión de los estándares de contenido se convierte en el currículo que se enseña de muchas maneras. Ésta es una de las razones por la cual es tan importante que los estudiantes con discapacidades tengan acceso a un currículo que sea enseñado por maestros que tengan una comprensión del contenido. Estamos convencidos de que los mejores maestros del contenido son aquellos que tienen una comprensión detallada del contenido y su trasfondo.

Narrador: La instrucción y la evaluación de los estudiantes con discapacidades también pueden reforzarse a través de acomodaciones y modificaciones. A veces es difícil distinguir entre estas dos herramientas.

Dr. McLaughlin: Lo importante no es determinar si una estrategia en particular es una acomodación, sino el propósito de esa acomodación. Es algo que intenta limitar el impacto de la discapacidad sin comprometer los estándares del contenido o las expectativas del rendimiento del estudiante. En contraste, una modificación es, no importa cual sea, y puede ser exactamente el tipo de estrategia o equipo que mencioné cuando hablamos de acomodaciones, pero en este caso, cuando se utiliza, en realidad cambia o altera el estándar de contenido o las expectativas del rendimiento.

Narrador: Para asumir la responsabilidad para la instrucción de todos los estudiantes, un grupo pequeño de estos estudiantes puede recibir evaluaciones alternativas.

Dr. McLaughlin: Una evaluación alternativa, como se ha empleado en IDEA y de acuerdo con otras leyes, se refiere a cualquier evaluación que no sea la evaluación estándar que ha sido diseñada o que se ha diseminado o administrado a la población general. …pero típicamente se consideren, o por lo menos en referencia a estos asuntos, aplicables sólo a un porcentaje o una proporción mínima de estudiantes con discapacidades, usualmente a los que presenten las discapacidades cognitivas más severas.

Narrador: No es fácil, pero el labor de mejorar la instrucción y la evaluación de los estudiantes con discapacidades es una meta importante. Con su nueva comprensión de como recopilar e interpretar los datos, así como los factores clave para el mejoramiento de la instrucción de los estudiantes con discapacidades, usted está preparado/a para dar inicios a esta tarea. !Adelante!

Revisitando los Pensamientos Iniciales

Piense usted en sus respuestas iniciales a las preguntas que se repiten a continuación. Después de trabajar con los recursos de este módulo, ¿todavía concuerda con sus Pensamientos iniciales? Si ha cambiado de opinión, ¿qué aspectos de sus respuestas modificaría?

La señora Flores y el señor Ericson están revisando los resultados obtenidos en las evaluaciones de todos los grados con el propósito de entender como las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades pueden mejorar. ¿Qué problemas piensa usted que ellos pudieran descubrir?

¿Cómo pueden la señora Flores y el señor Ericson utilizar el resumen de los resultados de las evaluaciones de la escuela para concentrar sus esfuerzos en mejorar las puntuaciones de los estudiantes con discapacidades?

¿Qué preguntas deben hacerles la señora Flores y el señor Ericson a los maestros de educación general y a los de educación especial?

Cuando esté listo, proceda a la sección de Evaluación.

Evaluación

Favor de contestar las preguntas que aparecen a continuación. Si tiene dificultad contestándolas, regrese y repase las páginas de Recursos y perspectivas de este módulo.

- ¿Cuáles son algunos pasos importantes en la interpretación de los datos de las evaluaciones de alto riesgo?

- ¿Qué es lo que establece la ley sobre la instrucción y la evaluación de estudiantes con discapacidades?

- ¿Por qué es importante que los estudiantes con discapacidades tengan acceso al currículo de la educación general? ¿Cuáles son algunas maneras de ayudar a estos estudiantes a tener acceso al currículo de educación general?

- ¿Qué son acomodaciones? ¿Evaluaciones alternativas? ¿Cuándo debemos utilizar cada una de ellas?