What behavioral principles should educators be familiar with to understand student behavior?

Page 3: Antecedents

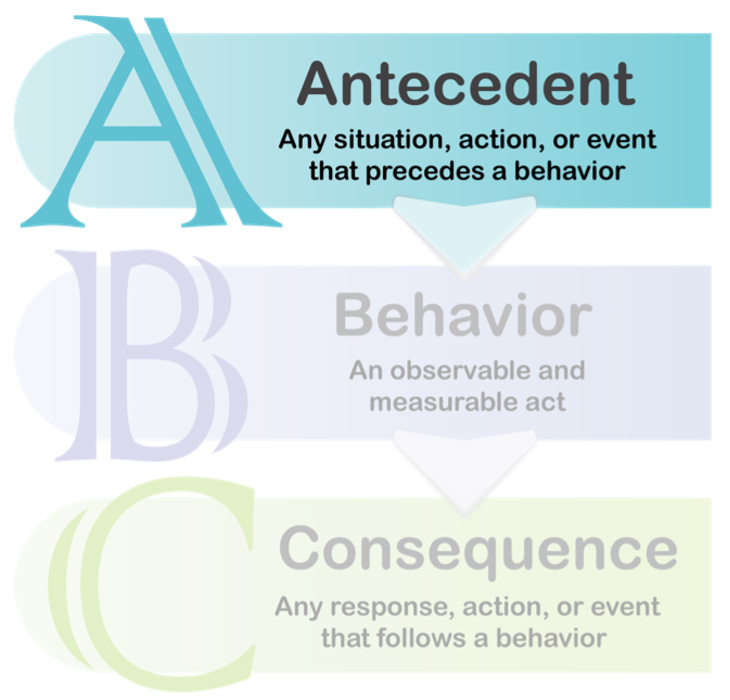

Now that you have learned about the ABC model, let’s take a closer look at antecedents. Recall that antecedents are events that happen prior to a given behavior and can make it more or less likely that a behavior will occur.

Antecedents—which involve what students see, hear, or experience in the environment prior to exhibiting behavior—can be viewed as clues to understanding students’ behavior. When educators understand how antecedents relate to behaviors and consequences, they can better predict individual behavior patterns and better support behavioral learning. Specifically, educators must understand that antecedents can influence student behavior by:

- Signaling the availability of consequences

- Changing the value of consequences

Signal Availability of Consequences

Did You Know?

Typically, multiple antecedents are influencing a behavior at any given time. For example, behavior can be influenced not only by antecedents that occur just before the behavior but also by setting events that have occurred hours if not days earlier. Setting events can include interactions on the school bus, at home, or in a previous class. These can also include educators’ actions (e.g., how they organize the classroom, structure lessons, communicate with students).

Antecedents signaling the availability of consequences let students know that given behaviors will result in reinforcing consequences (i.e., “payoffs”), as seen in the examples below.

Example 1: When the class bell rings (antecedent), students know they will be dismissed (consequence) once they have packed up their materials.

Example 2: When a teacher reminds students to raise their hands before asking a question (antecedent), students know they are more likely to be called on (consequence) when they raise their hand.

In this interview, Johanna Staubitz discusses and provides examples of both verbal and non-verbal antecedent signals. Next, Barbara Allen discusses antecedents that occur outside of the classroom, in addition to providing two examples.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Assistant Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

(time: 2:35)

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Antecedent signaling comes up all the time in classroom teaching, even if we don’t realize it. We use both verbal and non-verbal signals and, sometimes, verbal and non-verbal signals exist—even if we didn’t intend them to be such. When we do intend it, we might tell students what we want them to do. That alone influences their behavior. We’ve clarified the consequences for their cooperation, whether that’s with a behavioral routine or expectation or transition procedure, or even during academic instruction explaining how to use a new problem-solving process in math like solving for X in an algebraic equation. As we describe to students what the rules are for problem-solving, such as, “Find out what operation is happening between a number and X, and do the opposite on both sides of the equation” signals to them what behavior is going to produce reinforcement (the correct answer to the problem). And so we’re using signals through verbal interaction to clarify for students what they need to do, what behavior is necessary to produce reinforcement. This is also true when we explicitly teach rules and expectations as part of our Tier I supports in the classroom. We are literally telling students what behaviors will produce reinforcement or other consequences.

Other ways we use verbal signals include describing steps for a transition: “I’m going to transition you by groups. I’m going to call a group’s number. I want every other group to stay still, but I want that group to stand up, put their chairs on the table, and quietly line up at the door. [Check for understanding.] Okay, go.” non-verbal signals show up all the time as well, whether we intend them to or don’t intend them to. A good example of an intended non-verbal signal is that traffic light in the cafeteria. When it’s red, students should be silent. When it’s yellow, they should be talking very quietly, maybe whisper. When it’s green, they can talk at a conversational volume or numbered levels. If we hold up a Level 1 with our finger in the hallway, we expect our students—if this is their procedure and we’ve taught it to them—to speak at a Level 1 volume. But unintentional signals exist as well. The bell may ring to indicate a class period has ended, but a teacher may say, “Hey, my signal for you to pack up your bags is me saying, ‘It’s time to pack up your bags.’” But one or the other may actually signal that it’s time to move on. And then finally, regarding the intentionality of signaling, you might notice that if you put a writing prompt on the screen, students groan. Or if you get out the science textbook, you see students start to get out their science materials. Those things are all unprogrammed, unintentional non-verbal signals of what behaviors are going to pay off in that circumstance.

Transcript: Barbara M. Allen

An antecedent is something that occurs before the situation, and it’s an action or an event. It doesn’t just mean that it’s something that happened immediately before. It could have been something that occurred several days before. It could have occurred in the home. It could have occurred on the way to school. So going back and looking at the various antecedents helps me to say, “Okay, this didn’t just happen here at school. This came from somewhere else. And as a result, we need to address that in our plan to address the behavior.”

I have a couple of examples that I can share with you. I have a student that came to school, and every day around 9:00, he would go to sleep. And initially the school thought, “Oh, well it’s the class.” It wasn’t. He was not sleeping at night, so the antecedent actually was something that occurred the night before. By 9:00, he was tired, so he would go to sleep because the room was calm, it was quiet, it was peaceful. So what I had to do is talk with the parent and say, “This is a problem.” And she said, “I can get him to bed earlier and try to make sure he sleeps through the night.” That resolved the issue. We could have gone down the road of looking at, “Oh, it’s the class, and it’s this lesson.” And we would have been off track. A second example would be one where a student came in the morning and he had missed breakfast. When he got to class, he would get agitated because he didn’t have breakfast, and it had nothing to do with the class setting. It had to do with something that happened earlier, which was failing to have a meal. We provided a snack for him in the morning, and he always knew that snack was there. He could get it when he needed it, and that resolved that issue. So something occurring outside of the school’s control actually does affect the behavior of the student.

For Your Information

Educators can use proactive classroom management strategies as antecedents to promote desirable behaviors. Precorrection is one such strategy that allows educators to signal the availability of positive consequences through explicit instructions and prompts. For example, a paraeducator might gesture to a poster showing line behavior expectations before asking students to line up at the door. Because the class has learned expectations for lining up, this gesture serves as precorrection and signals that lining up appropriately will result in a positive consequence (i.e., earning a point in the classroom behavior system).

precorrection

Behavior strategy that entails reminding a student of appropriate behavior before the student can make an error; can be given either to groups of students or to an individual student.

For more information on this practice, view the IRIS Fundamental Skill Sheet below.

Change the Value of Consequences

Antecedents can also impact the value of consequences, making them more or less desirable to a student. Notice below how two different antecedents change a student’s motivation to engage in an academic task (behavior) that results in computer time (consequence).

Scenario A

Change in value of reinforcer—After a normal morning at school, a student missed lunchtime and recess for a dentist appointment. Diminished opportunities to interact with friends may temporarily increase the value of interactions with friends.

Effect on behavior—The student may be more likely to behave in ways that typically result in access to friends (e.g., whispering, passing notes).

Scenario B

Change in value of reinforcer—A student worked on an in-class assignment with their best friend prior to lunch and recess. Increased opportunities to interact with friends may temporarily decrease the value of interactions with friends.

Effect on behavior—The student may be less likely to behave in ways that typically produce access to friends (e.g., whispering, passing notes).

In this interview, Johanna Staubitz offers more examples of how antecedents can impact the value of consequences.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Assistant Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

(time: 1:33)

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Changes in the value of consequences also impact classroom teaching, and vice versa. For example, the value of peer or teacher attention at any given moment can impact how likely a student is to engage in behavior that produces peer or teacher attention or has in the past. So, for example, if they’ve had lots of access to peer attention that day, the value of it is relatively low. On a day where they’ve had a lot of access to it, they may be more likely to engage with instruction. But on days when students have been particularly deprived of peer attention, the value is very high. And it may be that no matter how engaging you try to make your instruction, you’re going to be dealing with more bids for peer attention through note passing or calling out or making crazy jokes. So think of a day when there’s been a long period of time where students take an exam and can’t talk to anyone. You might expect for the value of peer attention to be a little higher afterward than usual. The value of escape from work can change based on how hard the work is that’s been presented or for how long. So think about the extent to which a task is challenging or frustrating for a student. The higher the challenge or frustration, the higher the value of a break. So students may be more likely to act out in ways that get them sent out of the classroom, for example, if something really threatening in an academic sense is what’s about to happen because it’s going to impact the value of escape.