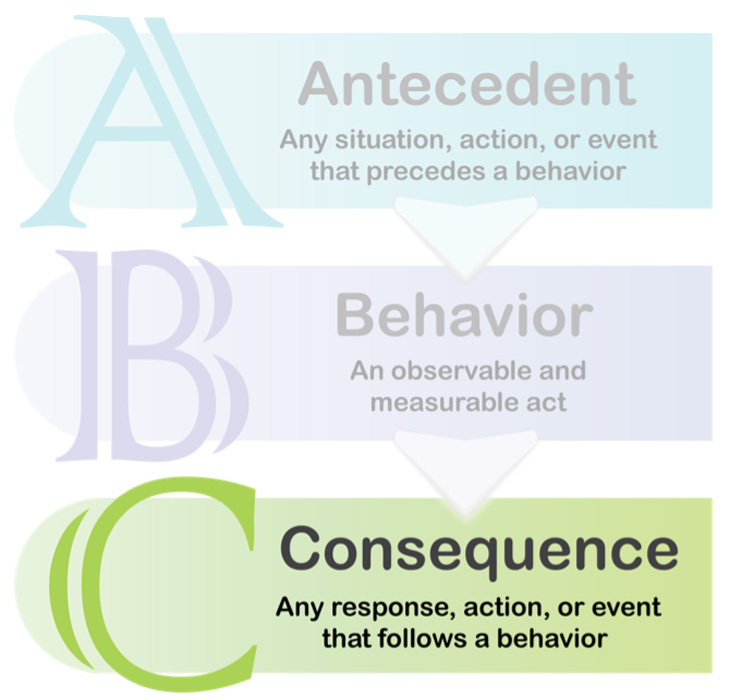

What behavioral principles should educators be familiar with to understand student behavior?

Page 4: Consequences

Now that you have learned about antecedents, let’s focus on consequences—or what students experience as a result of their behavior. A behavior and a consequence represent an “if-then” relationship: if the behavior happens, then a consequence results. Like antecedents, consequences can make it more or less likely that behaviors will occur. An important distinction is that antecedents influence the likelihood of the behavior occurring in the present while consequences influence the likelihood of behaviors occurring in the future. Consequences can involve something being either:

- Provided (e.g., earning a gold star, being given extra homework, gaining attention)

- Removed (e.g., an assignment is taken away, a privilege is revoked, attention is withheld)

For Your Information

Typically, consequences do not change behavior overnight. And experiencing a one-time consequence is not likely to increase or decrease the likelihood of a behavior occurring in the future. Instead, educators should consistently apply consequences to desirable behaviors to strengthen students’ skills over time and help students learn better ways to effectively communicate their needs.

For instance, an educator may provide attention (e.g., give a verbal reprimand) or remove attention (e.g., walk away from the student) when a student is being disruptive. In both cases, the disruptive behavior influences the amount of attention that the student receives from the educator. This change in the environment—the consequence—can increase or decrease the likelihood that a certain behavior will occur in the future.

When educators understand how consequences affect student behavior, they can adjust those consequences to help students learn expected behaviors that can replace undesired or challenging ones. Three types of consequences change student behavior: reinforcement, punishment, and extinction. As you will learn, using reinforcement to increase desired behaviors is generally more productive than using punishment or extinction to decrease undesirable ones.

Reinforcement is a consequence that increases the likelihood of a behavior occurring in the future. As a student consistently experiences a reinforcing consequence across time, they become more likely to engage in the behavior. In effect, reinforcement is the “payoff” of behavior and can occur due to:

- A natural consequence that is neither planned nor administered by an educator

x

natural consequence

An outcome of a student’s behavior that is neither planned nor administered by a teacher (e.g., after John throws food in the cafeteria, his classmates refuse to sit with him).

- An educator’s intentional actions

- A specific intervention designed to change a behavior

The table below shows examples of reinforcement in a classroom setting. In every case, notice how reinforcement increases the likelihood of the behavior.

| Behavior | Reinforcement | Change in Behavior |

| A student raises their hand. | The teacher calls on the student. | The student is more likely to raise their hand in the future. |

| A student completes a given task. | The paraeducator allows the student to take a brief break with a preferred activity. | The student is more likely to complete tasks in the future. |

| A student calls out silly answers. | Peers laugh. | The student is more likely to call out in the future. |

| A student plays a game on their phone during independent work. | The teacher sends the student to the office for the rest of the class period. | The student is more likely to play on their phone in the future. |

Caution: Because learning occurs through consequences, educators must consider how their responses may inadvertently reinforce challenging behaviors. In the last example above, the teacher may have sent the student to the office believing this consequence would decrease the undesired behavior. However, leaving the classroom may have allowed the student to avoid its demands, therefore making them more likely to play on their phone again. Although the consequence was intended to decrease the behavior, the opposite happened.

For Your Information

Behavior-specific praise is a simple yet highly effective form of reinforcement in the classroom. Using this strategy, an educator positively and explicitly acknowledges a desired behavior immediately after it occurs (e.g., “Johanna, thank you for cleaning up immediately when I rang the science bell.”).

To learn how to implement this practice, visit the IRIS Fundamental Skill Sheets below.

Punishment is a consequence that decreases the likelihood of a behavior occurring in the future. Although many people think of punishment as a disciplinary action in response to inappropriate behavior, punishment refers to any consequence that ultimately decreases the chances that a behavior will reoccur over time.

Like reinforcement, punishment can occur due to:

- A natural consequence that is neither planned nor administered by an educator

- An educator’s intentional actions

- A specific intervention component designed to change a behavior

The table below shows examples of punishment in a classroom setting. In every case, notice how punishment decreases the likelihood of the behavior.

| Behavior | Punishment | Change in Behavior |

| A student draws on a desk with markers. | The paraeducator removes the markers. | The student is less likely to draw on desks in the future. |

| A student approaches the teacher to show off their homework. | The teacher says, “Not right now” and waves the student away. | The student is less likely to show the teacher their homework in the future. |

| A student runs out of the classroom. | The principal reprimands the student. | The student is less likely to run from the classroom in the future. |

| A student answers a question correctly. | The teacher asks the student a difficult follow-up question. | The student is less likely to answer questions in the future. |

Caution: Occasionally, educators may find that their actions inadvertently punish desired behaviors. For example, note how the student who correctly answered a question considered the difficult follow-up question to be a punishment. Although the teacher likely did not intend to discourage the student from responding to questions in the future, the teacher’s action unintentionally decreased the likelihood of this behavior. In addition, when an educator repeatedly administers punishment, their presence alone can function as a punisher. When this happens, both desired and challenging student behavior can be suppressed and students can experience increases in uncomfortable internal behavior (e.g., thinking, feeling).

Extinction is a process in which reinforcement of a behavior stops, decreasing the likelihood of the behavior occurring in the future or eliminating it completely. For example, a student makes inappropriate comments during class to gain peer and educator attention (i.e., reinforcement). The educator directs students to ignore the classmate’s disruptive behavior and, over time, the student makes fewer inappropriate comments.

For Your Information

Educators sometimes inadvertently reduce or eliminate positive behaviors through extinction. Consider a student who helps an educator clean up a mess. An educator initially praises the student for this behavior, and the student begins to help regularly. When the educator unintentionally stops praising the student for helping, the student stops due to the discontinued reinforcement.

Caution: Educators should never use extinction with dangerous behaviors. Moreover, extinction can be difficult to implement because it:

Did You Know?

If educators choose to use extinction, they should always pair it with reinforcement of positive behaviors. This is more effective than completely withholding reinforcement.

- Depends on an educator’s ability to control all sources of reinforcement (e.g., peer laughter)

- Does not immediately reduce the target behavior

- Often results in an extinction burst—a situation in which the behavior initially increases, often suddenly or dramatically, before it decreases. For example, when an educator stops responding to a student who calls out answers in class, the student may initially increase the rate of calling out as they try harder to gain attention. The calling out may escalate to yelling or other extreme behaviors.

- Is associated with spontaneous recovery—the unexpected recurrence of behavior after it has stopped. For instance, a student who no longer tattles after an educator discontinues reinforcement might begin tattling again several weeks later.

- Can be confusing, and even traumatic, for students. Educators can offset these effects by building meaningful, supportive relationships with students and by being transparent with students about their behavior and the options that are being considered to address it.

For Your Information

Consequences can take many forms (e.g., tangible, social, activity). Their effectiveness can vary based on a student’s personal characteristics (e.g., age, cultural background, preferences) and can change over time. Furthermore, the same consequence may function as reinforcement for one student but as punishment for another.

Because the effectiveness of a consequence depends on the individual, educators should consider how different consequences may impact different students’ behavior. Educators may find it helpful to ask students about their preferences and incorporate this feedback into their instruction.

Although educators can use all three types of consequences, reinforcement is more likely to lead to meaningful change in student behavior than punishment or extinction. It is also the only type of consequence that increases behavior. Although punishment and extinction are inevitable inside and outside the classroom, neither teaches expected behavior. Furthermore, both have unpleasant collateral effects that can negatively impact students as well as student-educator relationships. Teaching new expected behavior using reinforcement should be an educator’s primary strategy for changing behavior in the classroom.

In this interview, Johanna Staubitz explains how educators can use reinforcement to facilitate behavior change and, at the same time, empower students and strengthen educator-student relationships. Next, she offers more information on the unintended outcomes of punishment.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Associate Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

Reinforcement

(time: 1:45)

Punishment

(time: 1:44)

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Reinforcement

Reinforcement is a very powerful way to change behavior because there are things that all humans need, like connection, play, rest, and others. We need these things to varying degrees and at varying times. Reinforcement is the way we can make it super clear this is what’s going to work and also, in using it, actually increase the probability of that behavior. We focus on reinforcement most when we want a student to learn new behavior or change an existing one because reinforcement is more likely to extend their skill repertoires in a healthy way. We can identify and explicitly teach behavior that will be more effective and more efficient in more scenarios, and it’s more consistent with age-appropriate or other social norms. Using reinforcement instead to empower the student may look like offering one or more appropriate ways to request a change to the assignment. And then, here’s the reinforcement part, making that change or negotiating some change with the student contingent on the appropriate request. So identifying and explicitly teaching a behavior to meet a given need, like accessing a certain type of attention or activity or getting a break from a certain task demand, we empower the student to consider their own needs and consider what socially appropriate actions they can take to get those needs met. So reinforcement is a step toward establishing a repertoire in which the student can take care of their needs and can have a better self-awareness of what those are. So relying on reinforcement helps us to extend students’ skills repertoire without some of those downsides and in a way that is going to grow skills while helping to develop or grow the relationship we have with the student.

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Punishment

Punishment can reduce behavior that isn’t as effective or efficient or socially appropriate, but only the behavior that is punished changes or decreases. Others are going to show up in its place because there’s still a need that has to be met. And if we leave what that behavior is that gets the need met to guesswork, chances are that what a student identifies or uses as an alternative means to get attention from adults or peers, for example—or a break from a task or access to a preferred activity—isn’t going to be the most socially appropriate, even if it is effective or efficient. Not only that, using punishment can actually worsen behavior because other behaviors will emerge that serve the same need as the behavior that’s being punished. Furthermore, individuals like educators who are using punishment procedures can start to function as punishers themselves. That is, their presence can suppress behavior or even evoke other inappropriate behavior that’s popped up in the place of a behavior that’s being punished. Consider a student who in the past has been written up for speaking rudely to a teacher, maybe in the context of asking for a change in an assignment requirement. Being written up may stop the student using that rude tone, but the teacher may then see an increase in eye rolling, pushing or slamming materials around, and general disengagement. None of these behaviors were issues before for the student. But if that rude tone related to some need, those other behaviors developed in its place. And they’re all more likely now in the presence of the teacher, just through the teacher’s association with giving the write-up or sending the student to the office.