What should educators understand about students who have trouble accessing standard print?

Page 2: Accessible Educational Materials

As you just learned, providing educational materials exclusively in text-based formats can create learning barriers for students with print disabilities. Educators can help eliminate these barriers by using accessible educational materials (AEM), which are designed or enhanced to effectively address the widest range of learner needs.

AEM can be made available in a variety of formats that provide the same information in different ways. Below are some of the most common formats used for AEM.

Accessibility is when:

acquire the same information

engage in the same interactions

enjoy the same services

© 2023 CAST, Inc. Used with permission. All rights reserved.

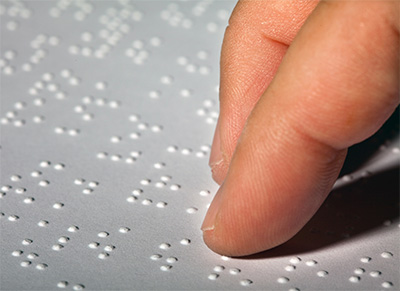

Braille—Braille is a tactile form of written language used by people with visual impairments (e.g., blindness, low vision). Patterns of raised dots are used to represent letters, numbers, and punctuation marks. Braille can be embossed on physical paper or reproduced on a refreshable braille display.

refreshable braille display

An electronic device that, when connected to another device such as a computer or tablet, displays text as braille, usually by raising and lowering different combinations of small pins.

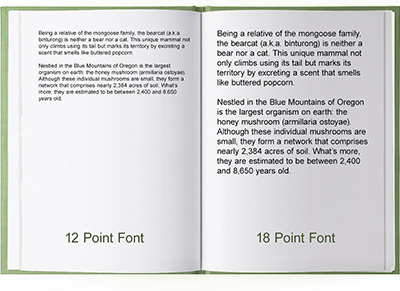

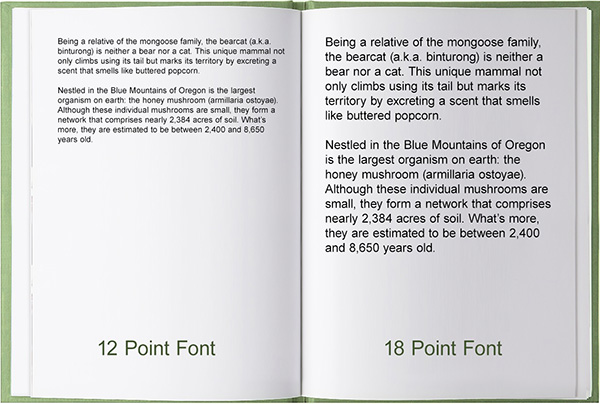

Large print—Materials in large print are typically used by people with visual impairments and are printed in text sizes larger than those used by the general population. A common guideline for large print is 18-point font or larger.

(View enlarged image)

Audio—Audio formats present content using either a recorded human voice or synthesized electronic speech, allowing readers to listen to texts. Customizable features may allow for adjustments to speed, volume, and voice (e.g., gender, age).

Digital text—Digital text formats present content on a computer, tablet, or other device. Readers can view and listen to text simultaneously as well as customize features (e.g., text size, color contrast, speed, volume).

Did You Know?

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Name given in 1990 to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) and used for all reauthorizations of the law, which guarantees students with disabilities the right to a free appropriate public education in the least restrictive environment.

In the past, accessible materials were typically developed on a case-by-case basis and were time- and labor-intensive to create. The 2004 reauthorization of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) introduced provisions to help schools provide students with disabilities timely access to AEM. Specifically, it established the National Instructional Materials Accessibility Standard (NIMAS) to guide publishers in meeting digital accessibility requirements. Publishers now use this technical standard to produce digital files of textbooks and other educational materials that can be easily converted into a range of accessible formats (e.g., braille, large print, audio, digital text). These formats are then made available to schools and students through various repositories such as Bookshare, the National Instructional Materials Access Center (NIMAC), and the American Printing House for the Blind Louis Database.

Students may use more than one format depending on their needs, the type of content, and the reading environment. For instance, a student with a visual impairment might prefer to see complex mathematical equations using a large-print textbook but opt for a digital text format of their history textbook. Another student who accesses digital text materials on a computer in the classroom might prefer listening to an audio format at home. Therefore, educators should not assume a single format will work for a particular student all the time. Rather, they must collaborate with students and families to consider individualized needs and contexts when making decisions about AEM formats.

Digital Accessibility

Compared to other accessible formats, digital text is the most flexible and adaptable. Consider a student with a visual impairment. Although they could be provided with a large-print book in 18-point font, this static material may still present a barrier for the student. However, digital text would allow them to further enlarge the font or adjust other settings to meet their needs. Another student with a reading disability could listen to a book in audio format, but the text-to-speech features of digital text would enable additional personalization like changing the voice of the speaker, adjusting the reading speed, and highlighting each word in the text as it is spoken.

Educators must understand that just because materials are digital does not always mean they are accessible. Digital materials that are not accessible include:

- A website featuring images that are not tagged with descriptive alt text for people who cannot view them

x

alt text

A written description of a digital image that is read aloud by screen reader software and displays on the page if the image fails to load.

- An e-book that is incompatible with assistive technology and therefore cannot be read aloud

- An improperly formatted document (e.g., heading structures, table formats) that cannot be navigated by a screen reader

Digital accessibility refers to the inclusive practice of removing barriers that prevent access to or interaction with websites, documents, and digital tools. To be accessible, features (e.g., adjustable font size and color, text-to-speech, alt text) must be built into digital text to allow for customization and flexibility. In this interview, Charles LaPierre discusses potential barriers to digital content and the importance of digital accessibility. He also offers tips on how to make resources, specifically PDFs, accessible.

Charles LaPierre

Principal Accessibility and Content Quality Architect

Benetech

Transcript: Charles LaPierre

Schools across the country rely on digital materials to deliver content, curriculum, and information necessary to learn. While many teachers assume that digital materials are accessible for all students, the reality is that digital does not automatically mean accessible. Students with disabilities face additional barriers when presented with digital content that is not accessible. Digital accessibility means that websites, educational materials, and tools are designed in a way that allows people with disabilities to use them effectively. It is a focus on making digital content accessible to everyone, regardless of their abilities. For example, when teachers use PDFs to provide information to their students, they may not understand that a standard PDF is an image, so the text is locked. In other words, a student is not able to adjust font size, color, or access text-to-speech, which may be the student’s primary way to best consume information.

Why is digital accessibility important? Digital accessibility is important for teachers to understand because it promotes inclusivity in the classroom; provides equal access to content; is aligned with global standards from the W3C, or the World Wide Web Consortium; and it benefits all students, not just students with disabilities; and, finally, fosters independence. So what can a teacher do? If you must use a PDF, check if it is accessible using a simple checker, such as check.axes4.com.

If you must make your own PDF, start with Microsoft Word and run its built-in accessibility checker to ensure there are no accessibility errors, such as missing alt text for images. Make sure to use proper headings using the built-in styled heading levels (one, two, three, etc.). Also, if you export to PDF, make sure you select either the PDF-A or PDF-UA option depending on your version of Microsoft Word. There might also be a checkbox “Documents structure tags for accessibility.” Make sure that is also selected. Consider using the free Microsoft tool from DAISY called WordToEPUB, which will export your Word document into an accessible EPUB. Again, making sure the original Word document is fully accessible using the built-in accessibility checker and ensuring proper styling of headings.

Benefits of AEM

Students with disabilities are entitled to timely access to AEM under IDEA and Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. However, accessibility is far more than a legal requirement. Educators are responsible for ensuring that all students have access to needed instructional materials so they can reach their learning goals. Below, explore some primary benefits of providing AEM in the classroom.

Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973

Federal law that set the stage for both the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, passed in 1975, and the Americans with Disabilities Act, passed in 1990, by outlining basic civil rights for people with disabilities.

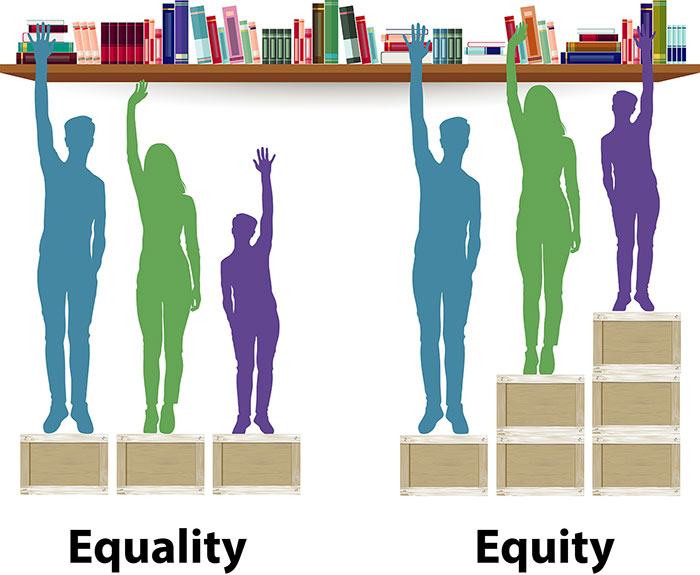

AEM promotes equity in the classroom by giving each student what they need to access the curriculum, rather than giving every student the same thing (i.e., equality). It is a common misconception that accommodations, including accessible educational materials, create an unfair advantage for students with disabilities. In truth, when educators provide students with materials that best suit their needs, they ensure that all students can access the same information at the same time. AEM levels the playing field and empowers students with print disabilities to develop the same knowledge and skills as their peers even when they require different formats to do so.

AEM promotes equity in the classroom by giving each student what they need to access the curriculum, rather than giving every student the same thing (i.e., equality). It is a common misconception that accommodations, including accessible educational materials, create an unfair advantage for students with disabilities. In truth, when educators provide students with materials that best suit their needs, they ensure that all students can access the same information at the same time. AEM levels the playing field and empowers students with print disabilities to develop the same knowledge and skills as their peers even when they require different formats to do so.

accommodation

An adaptation or change to educational environments and practices designed to help students overcome the challenges presented by their disabilities and to allow them to access the same instructional opportunities as students without disabilities. An accommodation does not change the expectations for learning or reduce the requirements of the task.

For Your Information

Universal Design for Learning (UDL) is a framework that supports equitable learning experiences for all students. Accessibility is foundational to UDL, and providing AEM is one way educators can ensure that their instructional materials are designed to be accessible from the start. To learn more about UDL, please visit the following IRIS Module cocreated with CAST.

AEM facilitates inclusion for students with print disabilities by ensuring that they have access to general education content. The use of AEM allows students with differing needs to learn together. Furthermore, it normalizes the idea that all students, including those who have difficulty accessing standard print, can learn and achieve the same goals.

inclusion

The practice of educating students with disabilities in the general education classroom using a variety of individualized services and supports.

AEM reduces cognitive load by easing the demands related to seeing, decoding, or physically manipulating print materials. When content is inaccessible, students with print disabilities must expend a great deal of effort trying to simply obtain necessary information. For instance, a student with a reading disability may struggle with word recognition, requiring them to dedicate significant energy to decoding individual words. This demand leaves the student with limited cognitive resources for comprehending the content. Providing AEM to students with print disabilities helps minimize unnecessary cognitive demands presented by printed text, thus enabling them to focus on the learning goals.

cognitive load

The amount of working memory resources being used for a task.

AEM increases learner agency by promoting student choice and self-advocacy. For example, students can determine which formats best suit their needs when educators offer them a choice of materials. In addition, students who understand how they best learn will be better prepared to voice their needs and advocate for accommodations in the future.

learner agency

The power a learner has to direct and make decisions about their own learning.

Research Shows

- Students with reading disabilities demonstrated improved reading comprehension when given access to text-to-speech tools to listen to text being read aloud.

(Keelor et al., 2020; Silvestri et al., 2022; Wood et al., 2018) - Access to digital text with customizable font size, color, and contrast increased reading fluency and comprehension among students with low vision.

(McLaughlin & Kamei-Hannan, 2018)

Activity

Remember the students with print disabilities you met in the Challenge? They all need AEM to access academic content. For each student below, select the accessible format(s) that would best meet their needs. Remember, a student may require different formats for different purposes.

Gema is a ninth grader with low vision. Although she can see printed text with the assistance of an electronic magnifier, this takes a great deal of effort and often causes headaches. Therefore, Gema often prefers to read content in braille.

|

✅

|

||

|

❌

|

||

|

✅

|

||

|

✅

|

Based on her preferences, Gema is most likely to access materials in braille format. However, there may be times when Gema would benefit from listening to text read aloud using audio or digital text formats. Although Gema may use large print for certain tasks, it might not be the best option due to her reported eye strain.

Thomas is a fifth grader who has cerebral palsy and uses a power wheelchair with a joystick. Thomas has difficulty interacting with physical books on his own, so he relies on someone to hold his book open and turn the pages. Alternatively, Thomas can access and control a computer or tablet using assistive technology.

|

❌

|

||

|

❌

|

||

|

✅

|

||

|

✅

|

Thomas would probably benefit most from reading digital text on a computer or tablet. Sometimes, he may prefer to use audio formats to listen to text without additional digital customizations. Braille and large print would not be useful for Thomas because he does not have a visual disability.

Liza, a third grader with a learning disability, has difficulty decoding printed words. After reading a passage independently, Liza typically struggles to answer basic comprehension questions. However, after listening to a story read aloud, she can accurately retell the events with many details.

|

❌

|

||

|

❌

|

||

|

✅

|

||

|

✅

|

Because reading printed words is a barrier for Liza, it would be best for her to listen to text read aloud in either audio or digital text formats. Braille and large print would not be useful for Liza because she does not have a visual disability.