How can educators determine why students are engaging in these behaviors?

Page 2: Functional Behavioral Assessment

As you’ve learned, low-intensity strategies can address most interfering behaviors, but some will require a more intensive, individualized approach. In these cases, understanding a behavior’s function is the first step toward addressing it. Without this understanding, an educator might use their entire bag of tricks in an effort to stop the behavior, only to find that nothing works.

As you’ve learned, low-intensity strategies can address most interfering behaviors, but some will require a more intensive, individualized approach. In these cases, understanding a behavior’s function is the first step toward addressing it. Without this understanding, an educator might use their entire bag of tricks in an effort to stop the behavior, only to find that nothing works.

Luckily, there is a better way. Recall that an FBA is a systematic process through which educators seek the “why” behind an interfering behavior. More specifically, an FBA is a diagnostic assessment that helps identify the environmental factors influencing an interfering behavior in order to hypothesize the behavior’s function and help identify ways to address it. As a systematic approach to deeply understanding an interfering behavior, the FBA process benefits students and educators by:

diagnostic assessment

in glossary

- Respecting student dignity: By assuming that interfering behavior is meeting a need, FBA teams avoid placing blame on the student. Instead, they use FBA results to identify the function of the behavior and to help determine strategies for meeting the student’s needs.

- Guiding instruction: Because FBAs can help identify underlying skill deficits that might contribute to interfering behavior, their results can aid teams in determining what skills (e.g., academic, social, communication) the student needs to be taught.

- Informing more effective interventions: Information gathered through an FBA helps teams design interventions that address the root cause of the interfering behavior. Such interventions are more likely to result in meaningful and lasting behavior change than those developed without an understanding of the behavior’s function.

In this interview, Mary-Austin Modic discusses how the FBA process can benefit both students and educators. Next, Johanna Staubitz explains how teams can determine if conducting an FBA is appropriate.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Associate Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

(time: 1:20)

Transcript: Mary-Austin Modic, BCBA, LBA

Conducting an FBA does help us determine why the student is engaging in the behavior. And when we know why or we know different components of why, then it can help us tailor a plan to meet their needs. It can help them realize they can be more part of the process: “This is why I’m doing this. How can I do this more appropriately?”

We have a student that is engaging in maladaptive behaviors. Maladaptive behaviors include tantruming, physical aggression, anything that’s disruptive to the learning environment. We know that escape is the function of the behavior, so that can help us first teach this student how to escape appropriately from the task. And then once we get that consistent, we can start to build their tolerance for the task.

Asking for an escape in an appropriate way might be using a break card, it might be asking a teacher to take a short walk with them, it might be sitting in the classroom’s peace corner for a certain amount of time before they return back to the task.

So just building that consistently, the student being able to ask for escape, and then we can start to push the academics slowly once we consistently teach the student how to appropriately ask for that escape.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

When a student’s behavior is not unsafe and it’s not impeding their educational progress, an FBA is not appropriate. Likewise, if their behavior is doing one of those things and is responsive to intervention, an FBA would not be needed. For example, if a student is calling out a lot in class (it’s not an unsafe behavior) and they’re performing adequately on their assessments (so it’s not impeding educational progress), an FBA would not be appropriate. If they were struggling in class but then responded to an intervention like check-in/check-out, for example, an FBA would still not be needed.

An FBA may be appropriate if the student were calling out so much that they were missing instruction and falling behind. However, other interventions need to be attempted and documented as ineffective before an FBA would be appropriate. For example, after reteaching expectations to the students, communicating with parents, and so on and so forth prove insufficient, the teacher should revisit and increase their use of other low-intensity strategies, such as behavior-specific praise, proximity, or precorrection. If those strategies are ineffective, especially after some problem solving and adjustment, an FBA may be warranted to identify functional reinforcers for calling out and to aid in identifying a placement behavior.

Let’s take a closer look at three questions to consider when determining whether an FBA might be appropriate.

| Question | Consideration |

| For whom? |

FBAs take considerable time and effort and are neither appropriate nor necessary for most students. The FBA process is typically reserved for students who display the most severe interfering behaviors or chronic patterns of interfering behavior that have not been effectively addressed by previous behavioral strategies and supports. Note: FBAs are not exclusive to students with disabilities. An individualized education program (IEP) or 504 plan is not a requirement for conducting an FBA. x

individualized education program (IEP) in glossary x

504 plan in glossary |

| For which behaviors? | FBAs are most appropriate for addressing behaviors that have a significantly adverse impact on the student’s progress or the classroom environment. Usually, these behaviors happen more frequently or with a greater intensity than most classroom behaviors. They could substantially hinder the student’s or classmates’ learning or might be dangerous in nature. |

| When? |

FBAs should be conducted when comprehensive classroom behavior management and low-intensity strategies (e.g., behavior-specific praise, precorrection, choice making) have not adequately addressed a student’s interfering behavior. Note: The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) also requires that an FBA be completed when a student with a disability is removed from school for more than 10 days due to behavior resulting from their disability. x

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) in glossary |

Once a team has considered these questions and determined that an FBA is appropriate, the next question to consider is whether parental consent is required. According to IDEA, there are some circumstances in which parental consent must be obtained before beginning the FBA process. Parental consent is required if an FBA is being:

- Used as part of an initial evaluation or reevaluation to determine a student’s eligibility for special education services

- Conducted in response to a disciplinary change in placement of a student with a disability

Alternatively, when an FBA is being used to identify a student’s needs and to select strategies to address their behavior in an educational context, formal consent is not required by IDEA. Of course, teams should always include parents as collaborative partners throughout the FBA process. Additionally, because individual states and districts might go beyond federal guidance and require parental consent in other situations, educators should always ensure they are following local policies and procedures.

Multi-Tiered System of Supports

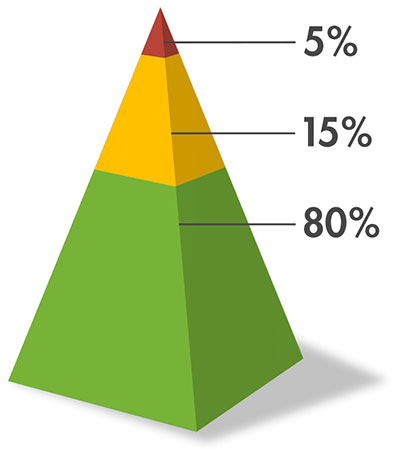

Many schools implement a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS), such as Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS), for school-wide behavior management. PBIS consists of three tiers—Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3—through which educators can provide a continuum of supports and services to promote appropriate behaviors and to prevent and address interfering behaviors. In schools that use the PBIS framework, FBAs are used to inform the most intensive interventions (Tier 3) for students with the most significant behaviors.

multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS)

in glossary

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

in glossary

|

Tier 3 (also referred to as tertiary intervention or intensive, individualized prevention) offers an individualized support plan based on assessment data (e.g., FBA). |

|

Tier 2 (also referred to as targeted or secondary prevention) offers targeted supports to groups of students with similar needs. |

|

Tier 1 (also referred to as primary or universal prevention) is effective schoolwide or classroom behavior management, which includes teaching students appropriate behavior. |

Note: A student who engages in behavior that poses a threat to the safety of themselves or others should immediately be referred for an FBA and receive Tier 3 supports.

High-Leverage Practices for Students with Disabilities

High-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education are foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. The information in this module aligns with:

High-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education are foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. The information in this module aligns with:

HLP 4: Use student assessment data, analyze instructional practices, and make necessary adjustments that improve student outcomes.

HLP 10: Conduct functional behavioral assessments to develop individual student behavior support plans.

For more information about HLPs, visit High-Leverage Practices for Students with Disabilities.

Returning to the Challenge

DJ’s and Presley’s school teams have both decided that an FBA is an appropriate next step to understanding and addressing their interfering behaviors based on the following information.

- DJ is now exhibiting a chronic pattern of off-task behavior frequently and consistently within the classroom.

- Attempts to address DJ’s behavior (e.g., redirecting him, moving his seat in the classroom, implementing a classwide reward system) have not been effective.

- DJ’s frequent verbalizations are causing significant disruption to the classroom environment, impacting both his own ability to learn and that of his peers.

- The standard consequences for Presley’s behavior (e.g., phone calls home, visits to the principal’s office) have not been effective.

- Attempts to prevent Presley from interacting with her peers are hindering her academic and social progress.

- Presley’s interfering behavior is dangerous due to its severity and the potential for physical harm.