How can educators determine why students are engaging in these behaviors?

Page 6: Descriptive Assessments

In addition to gathering information from indirect assessments, FBA teams should collect real-time data to gain insight into the circumstances surrounding the target behavior. Descriptive assessments involve observing the student in the natural educational environment and systematically recording information when the target behavior occurs. Ideally, an objective person (e.g., school psychologist, another educator, behavior analyst) will conduct these observations while the teacher goes about their usual instruction. This helps ensure that the data reflect the natural environment and the ways educators and peers typically respond to the behavior.

In addition to gathering information from indirect assessments, FBA teams should collect real-time data to gain insight into the circumstances surrounding the target behavior. Descriptive assessments involve observing the student in the natural educational environment and systematically recording information when the target behavior occurs. Ideally, an objective person (e.g., school psychologist, another educator, behavior analyst) will conduct these observations while the teacher goes about their usual instruction. This helps ensure that the data reflect the natural environment and the ways educators and peers typically respond to the behavior.

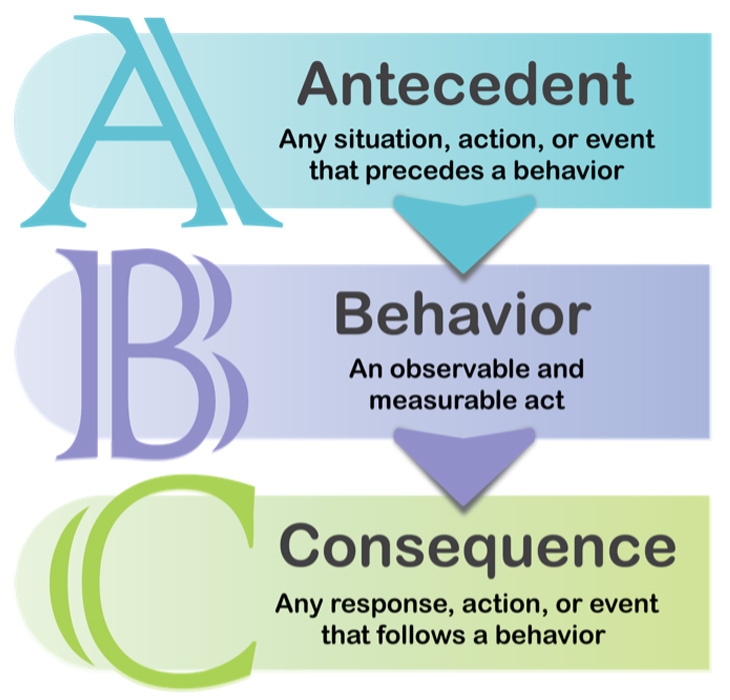

Most often, the descriptive assessment used for an FBA is antecedent-behavior-consequence (ABC) data collection. When collecting ABC data, the observer records the time, location, and a brief narrative for each observed instance of the target behavior as it occurs. This narrative is divided into three sections:

For Your Information

In addition to antecedents that occur just before the behavior, observers should also make note of any known setting events that are further removed from the behavior (e.g., confrontation with an adult outside of the classroom, not sleeping well the night before).

setting event

in glossary

- Antecedents: Any situations, actions, or events that happen before the behavior, including elements of the environment (e.g., instructional configuration, subject area) and any immediate triggers (e.g., an interaction with a peer, a loud noise, a transition).

- Behavior: Any observable and measurable act that aligns with the operational definition of the student’s target behavior.

- Consequences: Any responses, actions, or events that follow the behavior (e.g., teacher reprimands, peer reactions, incomplete work).

Note: Consequences refer to any change in the environment regardless of intent. It is important to record natural consequences as well as more deliberate actions taken to address the behavior.

natural consequence

in glossary

By recording specific details of what happened before and after the behavior, FBA teams can better distinguish what tends to trigger the target behavior in the moment and what reinforces it over time. Consider the descriptive data recorded for a single instance of a target behavior:

| Time | Setting | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

| 10:04 a.m. | Small-group reading | The teacher says, “Evan, your turn,” to signal him to read the next page aloud. | Evan yells, “No, I don’t want to.” | Other students ask him to stop while covering their ears. The teacher says, “Evan, it’s your turn to read.” |

Each occurrence of the target behavior should be recorded in its own row of the ABC data chart. Sometimes, behavior occurs in a sequence, with the consequence of one behavior acting as the antecedent for another. In the ABC chart below, notice how the teacher’s response (i.e., consequence) to Evan’s initial behavior becomes the antecedent that triggers a second instance of the target behavior. Recording the ABCs of each incident separately helps to capture key details about how the behavior escalated.

| Time | Setting | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

| 10:04 a.m. | Small-group reading | The teacher says, “Evan, your turn,” to signal him to read the next page aloud. | Evan yells, “No, I don’t want to.” | Other students ask him to stop while covering their ears. The teacher says, “Evan, it’s your turn to read.” |

| 10:05 a.m. | Small-group reading | The teacher says, “Evan, it’s your turn to read.” | Evan continues yelling and bangs his hands on the desk. | The teacher says “Let’s skip Evan today.” and moves on to the next student. |

Although a single behavioral instance might provide clues to its function, consistent data is needed to reveal trends. For this reason, multiple observations should be conducted so that ABC data are collected across different days and contexts until one or more patterns emerge. Such patterns are easier to recognize when ABC data are both thorough and precise. For example, narratives should specify any other people involved (e.g., educators, peers) and fully describe antecedents and consequences, even if they do not seem related to the behavior at first glance. Similarly, the narrative should detail exactly what the behavior looked or sounded like for each particular occurrence. When possible, it is also helpful to describe the duration and intensity of the behavior. It is far better to err on the side of including too much detail rather than too little, while taking care to prevent assumptions or implicit biases from impacting narrative descriptions.

In this interview, Bettie Ray Butler provides some considerations for educators when collecting ABC data (time: 2:40).

Bettie Ray Butler, PhD

Professor of Urban Education

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

Transcript: Bettie Ray Butler, PhD

Teachers and FBA teams should consider a few things when they are recording ABC data, the antecedent, the behavior, and the consequence. And critical self-reflection, introspection, is what I like to start with. And I know it seems out of place because we’re talking about the student’s behavior, but sometimes the antecedent behind the student’s behavior is the educator’s behavior. And so it’s always important to start with self first, to do a deep introspection of our own behaviors.

Secondly, observing classroom contexts and even desk arrangements. I know these are very simple things, but I think that they’re important when we’re talking about looking at these processes through a cultural lens because how desks are arranged could either indicate individualism or collaboration. And what they’re sitting on, and how long they’re sitting, and what is the front of the classroom versus the back of the classroom. How we design the classroom space to make it more comfortable and for it to be a space of collaboration and to encourage community I think it’s also important for FBA teams to consider. And knowing these things and being open to revising them and revising your ways of doing things, I think, will also show whether or not behaviors are more pronounced in this environment versus a separate environment.

And lastly, when you’re collecting this data, while pattern identification is critical in this process, but it’s not necessarily solely on the individual student, what is the teacher’s pattern of identifying these behaviors? What types of students are they identifying? Is there a disparity in the identification process and the subsequent consequences that immediately follow that process? Are they more punitive for certain students? Again, going back to that introspection, why do the teachers believe that this behavior exists in the first place? And then asking those very critical questions of, Is there data to support the reasoning why the teacher believes that this behavior exists? What outside of the teacher’s assumptions alone explain this behavior? Has the teacher done their due diligence and spoke with the families and spoke with the student to determine what may be happening in this situation?

Did You Know?

Behavior can be measured both qualitatively (using words) and quantitatively (using numbers). ABC data relies on qualitative notes about what happens before, during, and after an interfering behavior. Conversely, target behaviors can be measured quantitatively using systematic direct observations. Such data can take the form of:

systematic direct observation

in glossary

- Frequency recording—counting how many times the behavior happens in a given period

- Interval recording—documenting whether the behavior occurred during brief time intervals (e.g., 30 seconds)

- Duration recording—timing how long the behavior lasts

- Latency recording—documenting the time that elapses between when an instruction is provided and when the behavior begins or ends

Although systematic direct observation data can demonstrate how prevalent or severe a behavior is, they do not capture the context around the behavior (i.e., antecedents, consequences) that helps inform an understanding of its function. Therefore, qualitative ABC data are much more valuable for the purposes of an FBA. On the other hand, quantitative data from systematic direct observations are more beneficial for establishing a baseline and monitoring behavioral change once a BIP is implemented.

baseline

in glossary

Returning to the Challenge

Tasha’s FBA team creates a plan for the FBA team leader (the school psychologist) to conduct regular observations and record ABC data. The video below depicts one such observation period. During the video, Johanna Staubitz records the ABCs of each instance of the target behavior, explaining each step and demonstrating how to fill out the recording form.

Tasha’s FBA team creates a plan for the FBA team leader (the school psychologist) to conduct regular observations and record ABC data. The video below depicts one such observation period. During the video, Johanna Staubitz records the ABCs of each instance of the target behavior, explaining each step and demonstrating how to fill out the recording form.

(This VIDEO is coming soon.)

Activity

Now, let’s practice. First, review Isaiah’s target behavior.

Now, let’s practice. First, review Isaiah’s target behavior.

Target behavior: Isaiah initiates forceful physical contact with inanimate objects.

Examples

- Isaiah pushes papers and objects off his desk.

- Isaiah forcefully slams his hands or fists on a table.

- Isaiah clenches his fists.

- Isaiah crumples a piece of paper.

Non-Examples

- Isaiah kicks a backpack on the floor.

- Isaiah throws a book.

- Isaiah rearranges objects on his desk.

- Isaiah bumps into a piece of furniture.

View the videos below to observe Isaiah’s behavior during two separate observational periods, in science and social studies class.

Transcript: Science

TBA

Transcript: Social Studies

TBA

In the tables below, record each instance of Isaiah’s target behavior.

Note: These fields are provided for practice purposes only; your answers will not be available for downloading or printing.

Setting: Science class

| Time | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

Setting: Social Studies class

| Time | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

Setting: Science class

| Time | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

| Teacher says, “Okay, class, time to put your tablets away. We’re going to get started.” | Isaiah grunts, throws his head back while shaking his tablet, and continues working on tablet. | Paraeducator places hand on Isaiah’s table and says, “Isaiah, please find a stopping point so you can join us for the lesson.” | |

| Paraeducator places hand on Isaiah’s table and says, “Isaiah, please find a stopping point so you can join us for the lesson.” | Isaiah continues on his tablet for two minutes. | Isaiah puts the tablet down, opens notebook, and begins writing. |

Setting: Social Studies class

| Time | Antecedent | Behavior | Consequence |

| Teacher tells students to stop what they’re doing because it’s time to discuss with partners. | Isaiah throws pencil on floor. | Teacher ignores Isaiah and instructs class to turn to their partners to discuss. | |

| Teacher ignores Isaiah and instructs class to turn to their partners to discuss. | Isaiah pounds his fist on desk and groans. | Paraeducator comes to Isaiah’s side and says, “Isaiah, please pick up your pencil and put it back on your desk.” | |

| Paraeducator comes to Isaiah’s table and says, “Isaiah, please pick up your pencil and put it back on your desk.” | Isaiah pushes companion guide off desk to the floor. | Paraeducator says, “Hey, do you need to take a break?” | |

| Paraeducator says, “Hey, do you need to take a break?” | Isaiah does not respond but continues silently writing in his notebook. | Teacher and paraeducator allow Isaiah to continue writing in his notebook and not participate in the partner chat. |

For additional information about content discussed on this page, view the following IRIS resources. Please note that these resources are not required readings to complete this module. Links to these resources can be found in the Additional Resources tab on the References, Additional Resources, and Credits page.

Behavioral Intervention Plans (Secondary): Developing a Plan to Address Student Behavior (page 8) This module explores the steps for developing a behavioral intervention plan. It includes identifying appropriate behaviors to replace the interfering behavior, selecting and implementing interventions that address the function of the behavior, monitoring students’ responses to the interventions, and making adjustments based on the data (est. completion time: 2 hours). |