What strategies can educators implement to prevent or address challenging behaviors?

Page 1: Strategies to Address Challenging Behaviors

It’s not unusual for educators to feel overwhelmed when faced with challenging behaviors in their classrooms. In fact, both new and experienced educators report that managing challenging student behaviors is one of the most common difficulties they encounter. Challenging or acting-out behaviors are often described as inappropriate, aggressive, or even destructive and can range from minor behaviors (e.g., avoiding tasks, refusing to work, arguing) to more serious behaviors (e.g., threatening others, damaging property of others, damaging school property).

It’s not unusual for educators to feel overwhelmed when faced with challenging behaviors in their classrooms. In fact, both new and experienced educators report that managing challenging student behaviors is one of the most common difficulties they encounter. Challenging or acting-out behaviors are often described as inappropriate, aggressive, or even destructive and can range from minor behaviors (e.g., avoiding tasks, refusing to work, arguing) to more serious behaviors (e.g., threatening others, damaging property of others, damaging school property).

When these behaviors are not properly addressed, students, educators, and the classroom environment are negatively impacted. Effects can range from lost instructional time and lowered academic achievement to increased educator stress, frustration, and burnout. The good news is that managing these behaviors is something every educator can learn to do.

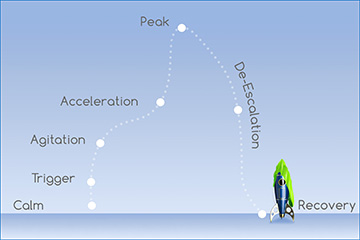

Before they can begin to address challenging behaviors, educators must first understand that most students who consistently exhibit challenging behaviors typically progress through a seven-stage process known as the acting-out cycle. As students progress through the acting-out cycle, minor behaviors that may have been overlooked in a busy classroom can quickly escalate to more serious behaviors. To address these types of behaviors, educators can use low-intensity strategies—easy-to-implement practices that require minimal time and preparation. By implementing these strategies, educators can:

Before they can begin to address challenging behaviors, educators must first understand that most students who consistently exhibit challenging behaviors typically progress through a seven-stage process known as the acting-out cycle. As students progress through the acting-out cycle, minor behaviors that may have been overlooked in a busy classroom can quickly escalate to more serious behaviors. To address these types of behaviors, educators can use low-intensity strategies—easy-to-implement practices that require minimal time and preparation. By implementing these strategies, educators can:

- Intervene early in the acting-out cycle

- Prevent challenging behaviors from escalating

- Successfully manage challenging behaviors in the future

Research Shows

- Many educators believe they lack the skills to manage a classroom and feel unprepared to address challenging behavior in a productive, evidence-based manner.

(Flower et al., 2017; Griffith & Tyner, 2019; Oliver & Reschly, 2007) - Students’ challenging behavior, as reported by teachers, has been shown to be related to emotional exhaustion (a key component of burnout) and reduced work enthusiasm.

(Aldrup, Klusmann, Lüdtke, Göllner, & Trautwein, 2018) - Teachers can implement low-intensity strategies to effectively address challenging behaviors and to facilitate academic engagement.

(Wehby & Lane, 2019)

When implemented effectively, these low-intensity strategies not only limit challenging behavior but also create a productive, safe learning environment where students are able to succeed academically, socially, and emotionally. This module will focus on the six low-intensity strategies highlighted in the table below. It also overviews differential reinforcement of alternative behavior (DRA) that can be used to manage challenging behaviors. These strategies can be easily implemented by educators (e.g., general and special education teachers, paraeducators, physical educators, music educators).

| Low-Intensity Strategies | Definition |

| Behavior-Specific Praise | Directing a positive statement toward a student or group of students that acknowledges a desired behavior in specific, observable, and measurable terms. |

| Precorrection | Determining when challenging behaviors tend to occur and then making changes to the classroom environment or providing supports for students both to prevent those behaviors from happening and to facilitate appropriate behavior. |

| Active Supervision | Frequently and intentionally monitoring students, during instructional and non-instructional periods, to reinforce behavior expectations and anticipate or prevent undesired behaviors. |

| High-Probability (High-p) Requests | Making a series of requests to which a student is highly likely to respond (high-p requests) before providing a request to which a student infrequently or never responds (low-p request) to increase the student’s ability to meet expectations. |

| Opportunities to Respond (OTR) | Giving students frequent chances to answer questions or prompts in a set amount of time to promote and reinforce student participation and engagement. |

| Choice Making | Providing structured options to facilitate a student’s ability to follow an instructional or behavioral request. |

| Differential Reinforcement | Definition |

| Differential Reinforcement of Alternative Behavior (DRA) | Reinforcing a positive alternative behavior that is a replacement for the undesired or challenging behavior. |

![]() More information on many of these strategies can be found on the Ci3T website: https://www.ci3t.org/PL

More information on many of these strategies can be found on the Ci3T website: https://www.ci3t.org/PL

All of the strategies listed in the table above have a similar goal—decreasing challenging behaviors and promoting desired ones. For this reason, many of these strategies can be used to target the same challenging behavior. Often, it’s a matter of what the teacher finds easy to implement in a given situation and what works best to address the student’s behavior.

If you have not already done so, we recommend that you visit the first IRIS Module in this series to learn more about the acting-out cycle:

Keep in Mind

When learning to implement these low-intensity strategies and differential reinforcement, you are not alone. You can seek support from others, such as:

- Mentor educators

- Special educators

- Behavior support team

- Behavior specialists

- Administrators

- School counselors

- School psychologists

multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS)

A preventive framework that integrates high-quality instruction, assessment (i.e., universal screening, progress monitoring), increasingly intensive and individualized levels of instructional or behavioral intervention, and data-based decision making to address the needs of all students, including struggling learners and students with disabilities. Two examples of MTSS are response to intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS).

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

A three-tiered framework (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary) that provides a continuum of supports and services designed to promote appropriate behaviors and to prevent and address challenging behaviors.

evidence-based practice (EBP)

Any of a wide number of discrete skills, techniques, or strategies which have been demonstrated through experimental research or large-scale field studies to be effective. Not to be confused with an evidence-based program.

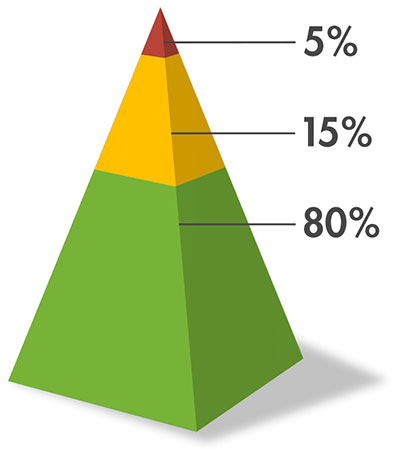

Tiered Systems

Schools that implement a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) are better equipped to support educators who may be struggling to address challenging behaviors in their classroom. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) is a multi-tiered system of supports designed to support students behavioral, academic, social, emotional, and mental health. PBIS provides clarity and guidance on what educators need to know and what evidence-based practices (EBPs) they can use to support students at Tier 1 (for all), Tier 2 (for some), and Tier 3 (for a few) levels of prevention.

Schools that implement a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) are better equipped to support educators who may be struggling to address challenging behaviors in their classroom. Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS) is a multi-tiered system of supports designed to support students behavioral, academic, social, emotional, and mental health. PBIS provides clarity and guidance on what educators need to know and what evidence-based practices (EBPs) they can use to support students at Tier 1 (for all), Tier 2 (for some), and Tier 3 (for a few) levels of prevention.

The six low-intensity strategies listed in the table above can be used as Tier 1 supports to increase engagement and minimize challenging behaviors for all students. However, as you will learn in this module, they can also be used as targeted support (Tier 2) for students with challenging behaviors by increasing their intensity or frequency. Additionally, this module will cover differential reinforcement of alternative behavior, which is often used as part of Tier 2 support for individual students.

For students who need more intensive individualized supports (Tier 3) visit the following IRIS Module:

For secondary students, PBIS provides additional resources to address circumstances unique to high school students and settings. Review the following resources to learn more about implementing PBIS in high school, incorporating student voice, and supporting students as they transition from middle to high school.

- High School PBIS

- High School PBIS Implementation: Student Voice

- Promising Practices For Improving the Middle to High School Transition For Students With Emotional And Behavioral Disorders

To learn about two models of tiered systems of support, visit the following centers.

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS)—As mentioned above, PBIS is a framework that provides foundational systems and identifies key practices of Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3. When PBIS is implemented correctly, students, teachers, and the school climate are all positively impacted. Outcomes range from improved social and emotional competence as well as academic success for students to improved health and well-being for teachers.

The Comprehensive, Integrated Three-Tiered Model of Prevention (Ci3T) is an integrative model that incorporates academic and behavioral supports, with the addition of supports to address social and emotional well-being.

High-Leverage Practices

The practices highlighted in this module align with high-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education—foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities.

The practices highlighted in this module align with high-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education—foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities.

More specifically, these practices align with:

HLP7: Establish a consistent, organized, and respectful learning environment.

HLP8: Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students’ learning and behavior.

HLP18: Use Strategies to promote active student engagement.

HLPs, which all special education teachers should implement, are divided into four areas: collaboration, assessment, social/emotional/behavioral practices, and instruction. For more information about HLPs, visit High-Leverage Practices in Special Education.