As a new teacher, what do you need to know about managing student behavior?

Page 2: Cultural Considerations and Behavior

Culture is a word we use to describe any of the practices, beliefs and norms characteristic of a particular society, group, or place. When cultural practices involve easily observable characteristics such as the clothing people wear, the food they eat, the languages they speak, and the holidays and traditions they celebrate, we often refer to these practices as visible. However, many cultural practices are more subtle: people’s interpersonal relationships, family values, familial roles and obligations, interactions between peers and community members, and beliefs about power and authority. It’s important for teachers to understand that culture can:

Culture is a word we use to describe any of the practices, beliefs and norms characteristic of a particular society, group, or place. When cultural practices involve easily observable characteristics such as the clothing people wear, the food they eat, the languages they speak, and the holidays and traditions they celebrate, we often refer to these practices as visible. However, many cultural practices are more subtle: people’s interpersonal relationships, family values, familial roles and obligations, interactions between peers and community members, and beliefs about power and authority. It’s important for teachers to understand that culture can:

- Influence the behavior of teachers and students alike

- Influence the behaviors and actions that occur daily in the classroom setting

- Affect teacher-student interactions

- Impact the extent to which teachers are able to manage behavior

For Your Information

Race is not synonymous with culture. However, racial identity is the product of social, historical, and political contexts, and thus students’ racial and cultural identities often share many commonalities.

It is also important for teachers to recognize that their students’ cultural practices and beliefs might well be different from their own. These differences, or cultural gaps, frequently lead to disparities in the ways teachers respond to behavior. Click here to review examples that illustrate certain specific perspectives and approaches that might result in cultural gaps.

cultural gap

glossary

| Differing Cultural Perspectives | |

| Respect for authority figures | |

|

Teachers are automatically regarded as an authority figure (based on role/position or age). |

As a new member of the community, teachers must earn respect. |

| Relationships with community | |

|

Teachers are expected to collaborate with family members or community elders. |

Students and families expect teachers to act independently. |

| Interpersonal space | |

|

Standing very close to someone when speaking is seen as violating personal space. |

Standing very close to someone when speaking indicates a close relationship. |

| Eye contact | |

|

Eye contact conveys listening. |

A lack of eye contact indicates deference or respect. |

| Verbal interactions | |

|

Verbally conveying information in a direct and assertive manner is valued. |

Verbally conveying information in an indirect and passive manner is valued. |

| Providing directions | |

|

Providing directions in the form of a question (e.g., “Can you join us for group time?”) implies an expectation to comply. |

Providing directions in the form of a question implies an expectation of choice or an option to decline. |

| Student engagement | |

|

Students who listen and remain quiet are respectfully engaged. |

Students who actively participate are engaged. |

| Family engagement | |

|

Families who participate in school events are considered to be interested and involved in their child’s education. |

There is a clear distinction between the role of the teacher and that of the family: Academics is the sole responsibility of the teachers while families provide instruction on skills and knowledge needed at home and in the community. |

Teachers should identify and anticipate potential cultural gaps that may influence their behaviors and interactions with students. To more effectively do so, teachers should have an understanding of their own culture and their students’ cultures. Click on the tabs below to learn more.

Before teachers can begin to navigate the complexities of the diverse student backgrounds in their classrooms, it is crucial that they take time to examine their own beliefs and cultural practices. Teachers may not realize how much of their daily routines and practices are influenced by their cultural practices and upbringing. From the holidays and traditions they celebrate, to the way they interact with others and show respect to those in positions of authority, many of the choices and actions teachers make each and every day are influenced by culture. These beliefs and actions can affect the way they operate their classrooms, including how they go about creating rules, procedures, and consequences, and execute their classroom behavior management plan.

Listen as Lori Delale O’Connor discusses why it’s important to understand one’s own culture, as well as how the culture in classrooms and schools impacts students.

Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Assistant Professor of Education

University of Pittsburgh School of Education

(time: 2:34)

Transcript: Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

It’s really important to understand one’s own culture and think about the ways that impacts students. I think one of the most important aspects of that is, without the recognition of one’s own culture, we start to see that the practices that we’re engaged in, our ways of being, our ways of knowing as sort of normal. And we may as a result demean ways of being and knowing that are different than ours as abnormal as sub-standard. So understanding one’s own culture allows us to see that culture itself isn’t neutral, that everybody has their own culture and their own ways of understanding, not just people we deem as different than us. And so that supports recognizing the culture of everybody in the classroom, including the teacher. It’s important to recognize that schools themselves have cultures, and classrooms themselves have cultures. Again, it goes back to this idea that when we don’t recognize that there is a culture of a place that has been developed over time and within a specific context, we start to see that as normal or neutral and everything that deviates from that as abnormal, instead of just seeing like, oh, hey, this developed over time and is the product of our expectations, of our ways of being, of our goals and ideas for the purpose of schools and the purpose of education. And those vary across time and space. And I think the culture of schools and classrooms, particularly within the context of the United States, there’s a very strong historical component that often we overlook, that we just sort of accept it as this is the way it is, rather than questioning how did it get this way and does it serve the needs of the teacher, of the building staff, of the students, of their families? Recognizing that every school in every classroom has a culture and that culture arises from the development of school itself within the United States, but also of that particular location is really helpful to recognizing the ways we can change or keep the different practices and policies that serve us well, and we can discard or change the things that aren’t serving us well to reflect the changing culture of the classroom and in the school.

Activity

To gain a better understanding of your own knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as to identify areas of strength and growth, complete the Double-Check Self-Assessment. When you are done, click the “Finish” button to get some feedback.

Note: If you have worked through Classroom Behavior Management (Part 1): Key Concepts and Foundational Practices, you may have completed this assessment.

Adapted from “Double-Check: A Framework of Cultural Responsiveness Applied to Classroom Behavior,” by P. A. Hershfeldt, R. Sechrest, K. L. Pell, M. S. Rosenberg, C. P. Bradshaw, and P. J. Leaf, 2009, Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 6(2).

Students and teachers may have similar cultural backgrounds and experiences, share only certain cultural experiences, or be altogether different from one another. When cultural gaps are present, students may not understand what is expected of them or how to interact with others. Learning about students’ cultures can help teachers:

- Identify areas in which students may need more support and explicit teaching of behavior rules and procedures

- Create rules and consequences that align with students’ cultural beliefs and practices

Following are some examples of how teachers can learn more about their students and their cultural backgrounds, experiences, and practices.

- Instruct students to write an autobiography.

- Have students interview each other about their family’s culture and practices then provide them with an opportunity to share what they learned about their peers with the class. Alternatively, instruct students to interview one or more family member(s) about culture and practices and ask them to share what they have learned with the class.

- Ask students or families for recommendations of books that represent their cultures and languages. Read these books together as a class.

- Encourage students to discuss how their cultural practices or beliefs may differ from how they are depicted in literature and other media.

- Invite family members to teach a lesson or to share something about their culture, traditions, holidays, or cuisine.

Listen as Andrew Kwok discusses the importance of teachers understanding their students’ cultures. Next, KaMalcris Cottrell highlights how her school creates a safe space where students are able to share their beliefs and values.

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of

Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

(time: 1:15)

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

It’s important to understand your students’ culture. Being a good teacher means that you need to understand who you’re going to teach. If you consider many other professions, those who succeed tend to really understand their constituents, and teaching is no different. Teachers need to recognize what makes their students tick and what motivates them and what expectations they may have of themselves and how those expectations can be transferred over into the classroom. And so the more that teachers can invest towards getting to know their students and their cultures, the more that they’ll be able to bring that information into the classroom and be able to apply it in meaningful ways so that their students can engage and participate and feel like a part of that classroom community and feel like they are being integrated and part of the learning process, as opposed to being individuals who are being spoken at and having to do learning one specific way. This opportunity to get to learn about their students opens up a variety of options for expanding their education.

Transcript: KaMalcris Cottrell

A few lessons that I’ve learned instructing or interacting with students from different cultures is to be as open-minded as possible to create a safe space for them to feel like it’s OK to share their different views and culture or their background or activities that their families may participate in that are foreign to me. But, again, if you’re open-minded, I’m always going to learn. And I think our school does an excellent job of providing this safe space. In the mornings, we have a caring community circle, and the teachers invite the students to join this circle and share on certain topics or even just something that the students would like to share that’s important to them. But I believe without this safe space, that sharing can’t take place. We talk about our behavior. What’s the expectation while we’re in the circle. We have the one person speaking. We do have non-verbal signals that the students can show that they agree or that they’ve done the same thing or they’ve had the same experience. We have a quiet hand raised if you would like to ask a question at the end. So I think with these parameters in place for this circle, this structure, this sharing time, it allows students to feel comfortable enough to share their different cultures and backgrounds. In 15 minutes every child has a chance to share, and you can always choose to pass and then at the end we’ll come back around if now you’re comfortable with sharing, you may do that at the end. So it’s very relaxed and nonjudgmental. You can share what you would like to share.

I believe the importance of understanding an individual’s culture is just to continue to give them validity. It’s hard to feel valid if you feel that you’re not understood. So if they are willing to share, I’m willing to learn. And I would hope people feel the same way about my culture. I’m willing to share. And I think if we can see other cultures through their view or from different points of view, it makes us that much stronger of a community.

To learn more about student diversity, view the following IRIS Modules:

Although many different cultures are represented in schools across the country, what is commonly perceived as “appropriate behavior” typically reflects white, middle-class cultural norms and values. These norms are reflected in classroom rules and procedures around behavior, communication, and student participation. Some students (or groups of students) may thrive within a particular school setting because their norms and practices align with these rules and procedures. In other words, they have the cultural capital—the acquired skills and behaviors that are accepted within a group and which give that group an advantage in a given environment. On the other hand, students with different cultural backgrounds may not innately grasp or understand traditional classroom rules and procedures because they do not align with what is considered appropriate or standard behavior in their home or community.

cultural norm

glossary

As noted above, when a student’s culture does not align with that of the classroom, this can result in cultural gaps. Cultural gaps can cause teachers to misinterpret students’ behavior—especially more subjective behaviors (e.g., disrespect, noncompliance)—which can lead to conflict. These conflicts can have a range of effects:

- Students feeling misunderstood or marginalized

- Escalation of misbehavior and aggression

- Higher rates of discipline referrals

- Students leaving school altogether

Let’s explore the effects of teachers misinterpreting student behavior in more depth. Black and Latino students, in particular, are subject to more frequent and harsher discipline compared to their white peers. This holds true starting as young as preschool and continues through high school. Oftentimes, this discipline is the result of subjective understandings of student behavior such as interpreting an action as “rude” or “disrespectful” rather than understanding that the behavior may stem from cultural differences. These subjective interpretations lead to negative outcomes for students that further exclude them from learning opportunities, including higher rates of suspensions, expulsions, and even students leaving school.

Checking in with Ms. Amry

Ms. Amry considers it respectful for her students to make eye contact when she is speaking to them. Jordan, on the other hand, has been taught that making eye contact is disrespectful to adults, and so he looks at the ground when Ms. Amry speaks to him. Ms. Amry’s understanding of culturally based responses is critical to deciphering Jordan’s intent. If the teacher does not understand Jordan’s culture, a seemingly insignificant action like looking at the ground could be misinterpreted as defiance, apathy, or lack of respect and could result in the teacher administering a negative consequence.

Ms. Amry considers it respectful for her students to make eye contact when she is speaking to them. Jordan, on the other hand, has been taught that making eye contact is disrespectful to adults, and so he looks at the ground when Ms. Amry speaks to him. Ms. Amry’s understanding of culturally based responses is critical to deciphering Jordan’s intent. If the teacher does not understand Jordan’s culture, a seemingly insignificant action like looking at the ground could be misinterpreted as defiance, apathy, or lack of respect and could result in the teacher administering a negative consequence.

Research Shows

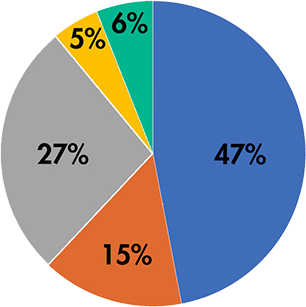

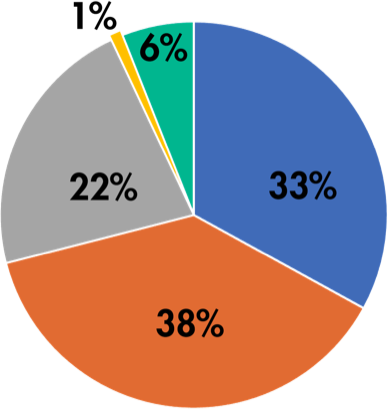

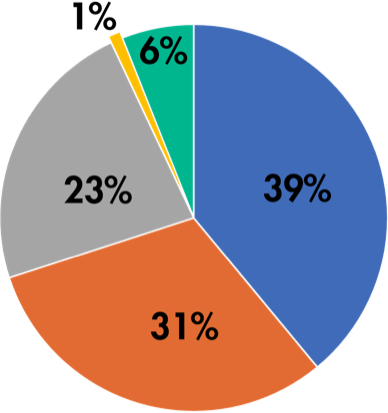

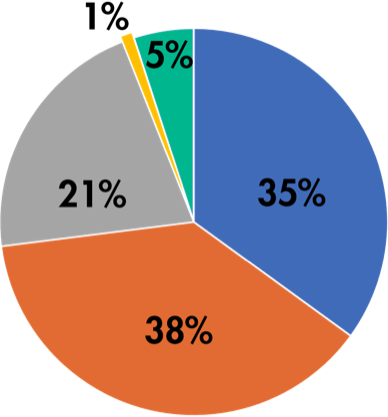

During the 2017–2018 school year, Black students in grades K-12 accounted for approximately 15 percent of total student enrollment. However, Black students were overrepresented in disciplinary actions. They accounted for approximately:

- 31 percent of in-school suspensions (one or more instances)

- 38 percent of one or more out-of-school suspensions (one or more instances)

- 38 percent of all expulsions (with and without educational services)

Students

In-School

Suspensions

Out-of-School Suspensions

Expulsions

Description: Cultural data graphs

The first chart is labeled ‘Students’ and is divided as follows: 47% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 27% Hispanic (gray), 15% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 6% other (green), and 5% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The second chart is labeled ‘In-School Suspensions’ and is divided as follows: 38% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 33% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 22% Hispanic (gray), 6% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The third chart is labeled ‘Out-of-School Suspensions’ and is divided as follows: 39% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 31% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 23% Hispanic (gray), 6% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The fourth chart is labeled ‘Expulsions’ and is divided as follows: 38% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 35% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 21% Hispanic (gray), 5% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

Additionally, data from the 2018–2019 school year indicate that Black students with disabilities ages 3–21 were overrepresented in disciplinary removals—incidences involving a student being taken out of an educational setting for disciplinary purposes (e.g., in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, expulsion, removal to an alternative educational setting, removal by a hearing officer). In the table below, note how the number of disciplinary removals for Black students is twice the average among all racial/ethnic groups and nearly three times the average for White students.

Average Number of Disciplinary Removals Among Students with Disabilities

|

||

| All | White | Black |

| 29 | 24 | 64 |

(Sources: National Center for Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs)

When teachers understand how cultural gaps negatively impact some students, they can more effectively develop a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan (e.g., rules, procedures, and consequences). Although the plan should be developed before the school year begins, it is important to be flexible and allow for changes throughout the school year as teachers learn more about their students. Some ways to make the plan more culturally sustaining are to:

culturally sustaining practices

glossary

- Ask for student input — Discuss components of the classroom behavior management plan (e.g., rules, procedures, consequences) with students. This discussion can include:

- Acceptable behavior at home or in their culture

- Fair or appropriate behavior in the classroom that allows everyone to be successful

- Compromises needed to address discrepancies in cultural norms. For example, some cultures prioritize the sharing of resources (e.g., pencils, paper) while others value independent ownership. A good compromise might be to allow both but with criteria for when each is appropriate.

- Seek family input — Learn more about the cultural practices of the student and family and what promotes the student’s success. This information can be gathered formally or informally through:

- Meetings (Meet the Teacher night, parent-teacher conferences)

- Frequent two-way communication (emails, phone calls)

- Build relationships with students — When teachers and students learn more about and develop a mutual respect for each other:

- Teachers gain a better understanding of what students need to engage in class and to succeed

- Students gain a better understanding of why particular rules and procedures are necessary to help the class run smoothly and to help the class succeed

- Encourage relationships among students — When students get to know each other, they are more likely to:

- Understand and respect each others’ differences

- Help one another to learn and grow

Listen as Lori Delale O’Connor discusses cultural capital and what it means for students in the classroom. Next Andrew Kwok discusses the discrepancies that may exist between the school and classroom culture and students’ cultures. Finally, he talks about developing a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan.

Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Assistant Professor of Education

University of Pittsburgh

School of Education

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

Transcript: Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Cultural Capital

Cultural capital is this idea that students and their families are familiar or are unfamiliar with what is deemed the “legitimate” culture within a society and in particular within a school. So it’s do you know how to engage the way the school expects you to? And if you do you’re rewarded and rewarded in the sense of you might get better grades. You are going to get opportunities because your teachers are going to say, oh, wow, what a great behaved student, what a high-achieving student. And a lot of that stems from not necessarily a student’s ability to do something but their understanding of how school works essentially, and their families understanding of how school works. When I think about families, some great examples are do you know how to contact a teacher in the way that the teacher expects and is deemed appropriate? And you’ll see cultural differences in that. In some cultures, it’s really believed that education is meant to be left to teachers, and there’s a high amount of respect. And so, as a parent, I’m going to trust that you know your job. You’re really good at it. And it would be an insult to you if I came in advocating for my student. Or, similarly, that actually the education is meant to happen between young people and the teacher. And so if there needs to be any intervention or if there needs to be conversation about it, it’s the role of the young person. In white, middle- and upper-class schools, there is a strong expectation that parents know how to intervene on behalf of their children. And the outcome of that often is that families might get what they want. And that might be an intervention in terms of my child needs something else. Perhaps reconsider my child’s grade. And similarly for young people there is an expectation of how you might advocate for yourself. And so they learn to argue in a polite and respectful way for what they want, and they learn to advocate for themselves from a very, very young age. And these sort of things are unstated. And if you are a young person coming from a family where you’re told to be deferent to the educator or to adults in general, and you’re really told not to speak unless you’re asked a question then you’re not going to know to advocate for yourself. And so basically with cultural capital, the idea is that it’s passed through families, and it helps them do better in school. If the ways that families know and value education aligns with the ways that the schools, their young people grow to also know and value education.

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Discrepancies between classroom and students’ cultures

The culture of schools and classrooms is really important for teachers to consider, particularly in thinking about the structures that make up education and schooling. What we already know about the cultural gap within the classrooms between teachers and students, we need to think about ways to alleviate that gap and allow primarily minority students to learn within a predominantly white and female school. The discrepancy means that the faculty and the teachers need to actively consider the environment that students are placed in and then think that it comes from mostly one or two traditional ways of understanding learning but more specifically as it relates to classroom management. One or two specific ways of how to behave and how to act within a classroom or a school environment, those sort of ways of acting and behaving does not necessarily always align with how other cultures think about or process appropriate behavior. The idea of misbehavior has multiple different definitions, and the way it can look in one certain classroom or within one certain school can differ, and without specifically aligning that or coming to an understanding of what that can look like there’s going to be discrepancies. And for teachers to be more culturally responsive, they need to understand that there are traditional structures within the school and within the classroom that need to be addressed, whether it needs to be changed directly or incorporate students’ voices and their opinions and perspectives so that the students can succeed within that environment.

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Developing a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan

Many teachers are often wanting to establish a certain type of classroom without any sort of flexibility. They have an idea of the classroom, and they want to stick to that and make all students within that classroom abide by that particular structure. Beginning teachers in particular, they’re often focused on maintaining authority and being able to essentially control the kids, be able to have them listen and do what they want to do in order to follow through on their lesson plan. But that’s not necessarily culturally responsive in the sense that it’s not necessarily considering what the students need in order to succeed within the classroom. So in order to consider a culture within these behavior management plans, often the easiest way to integrate that is through student input, being able to allow for opportunities for students to help create some of the structures, whether it’s the rules or procedures, and thinking about what it is that not only allows the teacher to succeed in the classroom but also what it takes for those individual students to engage with the material and be able to be as successful as they want in the classroom.

Other ways that behavior management plans can be more culturally sustaining would be to have the teacher build relationships with the students or to have the students have positive interactions with one another. In order to incorporate student input, the teachers really need to know their students and be able to understand what helps them to learn. And so, in order to do that, teachers often just rely on a beginning-of-the-year get-to-know-you paper, but students’ needs are individual and they are evolving and developing over the course of the year, and so the teacher constantly needs to check in and to get to know them and even share bits about themselves with the students so that they can build a strong bond that can then allow the teacher to understand what allows those students to engage with the material. And the same goes for allowing opportunities for the students to build relationships with each other, to get to know one another so that they can collectively learn, as well. It’s difficult for the teacher to be able to differentiate one lesson 20, 30 different ways for each individual within the classroom, but if they can think about collective similarities across students and see how they interact with one another and how they can help one another to learn and grow, that will allow for opportunities to change and adapt these structures within the system. Then the last bit would be to also consider families and community and peer teachers in considering additional factors that can help teachers succeed in building an effective classroom management plan.

Keep in Mind

Many classrooms include English learners (ELs) who are in the early stages of learning English or are still acquiring academic English language skills. What may appear as noncompliance to a verbal/written instruction or rule may in fact be a language misunderstanding. To support ELLs in understanding classroom rules and procedures, teachers should:

English learner (EL)

glossary

- Model appropriate behaviors and expectations

- Use pictures or other graphics to support language comprehension

- Use positive statements (e.g., “You can sit down.”) instead of negative statements (e.g., “Don’t get up from your seat.”)

- Use peers/school staff who speak the student’s home language to help explain rules and procedures

- Provide the rules and procedures in the student’s home language (when possible)

To learn more about English learners, visit the following IRIS Module:

For more information on cultural influences on behavior, view the following IRIS Module: