How can faculty design their online courses?

Page 1: Planning an Online Course

The information on this page was adapted from How to be a Better Online Teacher, Understanding by Design, and Course Planning with Backward Design.

Let’s be honest, the past few months have been bracketed by uncertainty, exhaustion, frustration, and stress. Each of us has been inundated with well-meaning sentiments of cooperation, mutual purpose, and support. We’ve heard “We’re all in this together” and “the new normal” so often the words have started to lose meaning.

Let’s be honest, the past few months have been bracketed by uncertainty, exhaustion, frustration, and stress. Each of us has been inundated with well-meaning sentiments of cooperation, mutual purpose, and support. We’ve heard “We’re all in this together” and “the new normal” so often the words have started to lose meaning.

That said, we all have work to do ahead of the coming academic year. In this IRIS Module, we’re going to break down steps to help prepare and maintain your course for and during a variety of circumstances. We will also offer some practical tips and strategies to make this process easier. Many of these might apply to you immediately; others may become relevant if or when conditions at your institution change.

And another thing before we begin: It’s okay to be frustrated. It’s okay to go slow. Not everything can or will happen at once. Maybe most importantly, just start with one thing.

Say that with us again: Just start with one thing.

You can do this. You will do this. We’re going to show you how.

Key Terms

A number of terms will be used repeatedly throughout this module. Here are the most important. Click on each for a definition.

| asynchronous | hybrid course | module | |

| blended course | learning management system (LMS) | synchronous |

asynchronous

Term used to describe a course structure that allows students to complete prescribed activities and tasks at such a time as their individual schedules allow; should not be confused with “self-paced courses,” in that asynchronous courses require intermittent student interaction and collaboration.

blended course

A type of instruction that involves face-to-face class sessions that are accompanied by online materials and activities–essentially a “blend” of learning that occurs in both brick-and-mortar and online environments. A fundamental component of a blended course is that online learning does not replace face-to-face class time. Rather, it is meant to supplement and build on content discussed in the classroom. Although this term is often used interchangeably with “hybrid learning,” hybrid learning involves more online interaction.

hybrid course

A type of instruction that involves a mixture of face-to-face and online learning in which the online components replace a portion of face-to-face class time. This allows students to complete some class activities at such a time as is most convenient for them. Although this term is often used interchangeably with “blended learning,” blended learning involves more face-to-face interaction.

learning management system (LMS)

Any of a wide variety of proprietary online platforms through which virtual courses can be conducted. Common tools include content-delivery systems, assessments, and communication options that offer students a number of ways to keep in touch with their instructors or one another.

module

A unit of organized information common to online courses; modules allow instructors to deliver sequenced learning materials and activities to their students via their institutions learning management system.

synchronous

Term used to describe an online course or other activity in which students are together in class at the same time, or a class activity that takes place in real time. All students participate in the task at the same time.

Course Delivery Options

As you well know, the worldwide coronavirus pandemic has changed how colleges and universities are able to provide instruction this year. Many are offering a range of course options, including face-to-face, online, and hybrid (sometimes referred to as blended). It’s one version of hybrid courses that is of particular concern to many instructors: One involving some mix of asynchronous and synchronous class sessions with a combination of in-person and virtual attendance. This is especially the case when circumstances necessitate a scheduled rotation of in-person groups due to classroom capacity and social distancing requirements. Further complicating matters, more than a few institutions have instructed their faculty to plan for a combination of face-to-face, hybrid, or online instruction at the beginning of the semester but also to prepare to transition to fully online should health and safety conditions on campus or in the community so necessitate.

As with anything, online instruction has both benefits and drawbacks. Foremost among its benefits, it helps safeguard the health and safety of students and faculty, as well as that of anyone with whom they might subsequently come into contact. Online learning also enables increased access for students not otherwise able to attend in-person classes. The major drawback to online instruction is that many faculty have little or no experience with it and, therefore, are not confident in planning or delivering a course based around it.

The good news is this: Just because online teaching is different than the in-person variety does not mean you can’t build on your own strengths and usual ways of doing things. Think about what you do well during face-to-face instruction. Maybe you excel at leading engaging discussions, or maybe you create wonderfully inventive group activities. As we will discuss, there are all kinds of ways to translate these strengths to a virtual setting.

Another important thing to think about: implicit practices. Just as we all have strengths that we are aware of, think about, and plan, so, too, do we have strengths that we just do naturally. This might be something like making your students feel welcome and valued, using especially vivid and incisive examples, or creating an atmosphere of cooperation and teamwork. These are strengths—sometimes hidden strengths—that you might need to spend some time reflecting on, explicitly planning, and reimagining how they might play out in an online environment.

Even if you are teaching a hybrid course, you should probably begin your planning process by developing a fully online version first then work from that to plan for the hybrid option. Joe Bandy, Assistant Director of Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching, is one of the instructors for the Online Course Development Institute upon which this IRIS Module was developed. Here, he offers some reasons why you might want to develop a fully online version of your course prior to planning the hybrid version.

Joe Bandy, PhD

Assistant Director, Center for Teaching

Vanderbilt University

Joe Bandy, PhD

Two advantages to planning a fully online version of your course

Moving from a face-to-face class to an online class is a much more difficult transition, as many educators encountered in the spring when we shifted online. It takes time and planning to move synchronous activities into asynchronous activities the students can complete on their own time apart from a common videoconference or class time. It takes time also to learn the tools that you may want to use, from course management systems to videoconferencing to common note-taking platforms. It takes time to understand how to also create social and teaching presence through those platforms with students when you’re not in the same socially proximate space every class period. So if you believe you might have to move your course online at any time, it’s probably best to go ahead and spend the time necessary to make it engaging and productive for your students.

A second reason that designing an online course makes you a more intentional and thoughtful teacher generally—whether you’re teaching online or face-to-face, since it asks you to think more explicitly about how you will scaffold activities and assignments, whether that’s asynchronous or synchronous so that you can move students in a scaffolded way towards the course learning goals—we find that those who are designing online courses are often thinking more carefully and intentionally about that than sometimes face-to-face instruction requires, since many feel comfortable just improvising once they get into the classroom. In online courses, you have to think things out a bit more clearly and can therefore hopefully add a bit more clarity and detail and structure to your courses and make it more purposeful and meaningful for your students.

Joe Bandy, PhD

Two disadvantages to planning only the hybrid version of your course

I think you might be setting yourself up for a lot more challenges later. We may be moving fully online, given how the pandemic changes and what kinds of policies, what kinds of infection rates we see and what kind of health-and-safety precautions schools might try to implement later. So if we move to an online environment then it’s probably best to go ahead and make sure your course is prepared for that. We also find it’s just easier to move from online to face-to-face than it is from face-to-face to online. So if you have an online course and you’re ready to go online, if you have an online course and you’re teaching hybrid then those students who will be online will have a full set of resources. And you can add components that are face-to-face for those students who will be face-to-face with you in the classroom. The more you can do that, setting up your online course to be fully accessible to all students, the more access, the more equity, the more clarity and structure it’s going to have for your students, no matter who they are and how they’re learning.

Key Considerations for Online or Hybrid Courses

Whether you’re converting a face-to-face class to an online one, creating an entirely new online course, or developing a hybrid course, there are practices we think will be helpful to you. Some of these might be things you incorporate more-or-less “automatically” in a face-to-face course but might find that you need to address more intentionally in an online or hybrid course. Click on each of the items below for a brief overview. We’ll offer further explanation and examples on subsequent pages.

A good rule of thumb is to invest at least as much time planning and teaching your online course as you would a typical face-to-face course. Let’s say you average between 8 to 12 hours a week on a given face-to-face course. This includes lesson prep, actual teaching time in the classroom, and grading. For your online course, you should schedule the same amount of time to be engaged and available to your students, to respond promptly to their emails, and to provide feedback, among other tasks. Keeping students engaged and focused in a typical class can sometimes be difficult. In an online environment—with its host of distractions—doing so can require more finesse and planning.

By its very nature, online instruction can make it difficult for students (who typically are working alone) to ask for or receive clarification when they review instructions for an assignment. It’s up to you to explain up front and as clearly as possible what they will need to show or do to satisfy the assignment’s requirements. This will help you avoid spending time later answering questions from students who for whatever reason didn’t initially understand what you wanted them to accomplish.

During face-to-face instruction, you typically scaffold information—that is, you begin with foundational knowledge or skills and then gradually, systematically build on that with more complex concepts. Likewise, you most likely model your thought processes for your students—offering examples and analogies or asking critical questions to help make sense of different theories and approaches—to connect ideas and create deeper understanding. You might even do this more-or-less automatically, without planning to do so in advance, something more difficult in an online, virtual environment.

Solution: Plan ahead. Plan to scaffold information. Plan to model. Think through your learning activities and assessments. By doing so, you will increase the likelihood that your students have the opportunity to build—step-by-step, as they would in a face-to-face course—the knowledge and skills you expect them to learn.

Because online teaching changes the way we conduct in-person discussion, the use of examples for clarification is even more crucial than usual. Consider a face-to-face course. It’s a simple thing for students to request further explanation. In response, you offer examples or suggest new and different contexts. When you teach online, you should expand this tendency. Screens and cameras create a distance in which meaning can become blurred or muddied. Recognize this limitation and be active in creating clarification, context, and deeper understanding.

Welcoming students to a new class is a familiar process for most faculty. Keep in mind, however, that what might work perfectly well in-person may not be as successful or effortless in a virtual environment. You might have to work harder to make students feel welcome and comfortable, just as you might need to work harder to get them engaged and maintain their participation and interactions with you, their fellow students, and the information you expect them to learn.

Difficult moments and uncertainty neither diminish nor dispel our obligation to student accessibility and equity. Quite the contrary. More so even than during in-person courses, you should make certain that content, learning activities, and assessments are accessible to all students regardless of ability (e.g., visual impairments, learning disabilities) or technology capabilities. You should also keep in mind your students’ cultural and linguistic backgrounds, among other factors.

Developing Your Course

Adapted from Center for Teaching, Vanderbilt University; and McTighe & Wiggins, 2012.

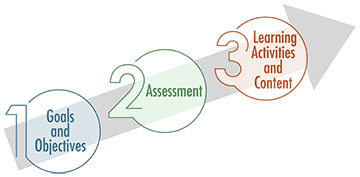

We recommend you develop your course using the principles of backward design. You can use this approach to guide your instruction and to effectively design lessons, units, and courses. With this method, you begin by developing your learning goals—what you want your students to achieve by the end of the course—and work backward from there to develop assessments, learning activities, and content, in that order.

Once you have identified the learning goals, it will be far simpler to develop assessments and instruction that fit your course goals and learning objectives. In other words, you will ensure that these instructional tasks are intentional and purposeful and eliminate those that do not support the intended learning goals. Following are the stages of backward design.

- Identify course goals and learning objectives. Determine what students should know and be able to do at the end of the course. Also determine what students should know and be able to demonstrate at the end of each unit or module. What do you want your students to learn?

- Develop assessments. Determine acceptable evidence to show whether students have achieved these learning goals. How will students demonstrate what they know and can do?

- Plan learning activities and content. Identify learning experiences, instruction, and resources that will help students gain the knowledge and skills they need to achieve the learning goals. What will you teach and how will you teach it?

Digging Deeper: Backward Design

Each page in this module provides an overview of key topics in the online course design process. Each Digging Deeper box provides links to more in-depth coverage of those key topics.

The links below take you to information from two of our favorite expert sources of information about online course design:

- Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching

- Indiana University’s Teaching Online self-paced course, hosted on the UC Davis Canvas system

![]()

- Understanding by Design Vanderbilt University, Center for Teaching

- Course Planning with Backward Design Indiana University/UC Davis

Adriane Seiffert, recipient of the 2018 Harriet S. Gilliam Award for Excellence in Teaching by a Lecturer or Senior Lecturer, learned the principles of backward design during Vanderbilt University’s Online Course Development Institute (OCDI) early in the summer. She then applied those principles to a course she taught during a summer session. You’ll hear more about that process later in this IRIS Module. Below, she discusses her overall impression of the differences in the planning process (time: 1:24).

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Senior Lecturer and Research Assistant Professor of Psychology

Vanderbilt University

Adriane Seiffert, PhD

Well, like many faculty, my only online experience was spring 2020, where suddenly I went from an in-class experience to an online experience. I had never done anything online before then, and I admit I didn’t have much of a plan in the spring either. I didn’t really put together much other than record videos and try to get as much online as possible and meet with my students over Zoom.

The thing that I took away most out of this spring term was that this is a whole different way of teaching. It’s entirely new. And you really have to start really thinking about it as starting teaching all over again and learning some of the same skills in a whole new way. I think the biggest difference is that you want to change things up a lot. So when you approach a face-to-face class, you have a plan of things that you’re going to do, but you may not have planned out every moment before you get there. You know, you have that ability to kind of play things out as they come along, to follow discussion if it needs to be, or move to some other part of the lecture if you want to cover that some more. But with an all online class, it’s a lot more difficult to do that. There isn’t as much feedback from the students and there’s not as much interaction that you can use. So you really have to plan a lot more in advance.

Getting Started

Tips

Tips for navigating the rest of this IRIS Module:

- Each page in this IRIS Module includes a range of information from basic to advanced.

- If you already have a basic knowledge of the page content and want more information, click on the

resources in the Digging Deeper boxes (denoted by the icon on the right), all of which go into greater depth on the topic at hand.

resources in the Digging Deeper boxes (denoted by the icon on the right), all of which go into greater depth on the topic at hand. - Access the content that is relevant to your needs. Feel free to skip anything that is not.

On the following pages of this IRIS Module, we’ll look more closely at this concept of backward design. You can use this process to convert a face-to-face class to an online one, develop an entirely new online course, or create a hybrid course. The stages of this process, plus information on online course design, are indicated below and will be discussed in more detail on subsequent pages.

- Course goals and learning objectives

- Assessment

- Learning activities

- Content

- Modular structure

- Final adjustments and ongoing revisions