How can faculty deliver and refine their online courses?

Page 6: Building the Course

Information on this page was adapted from:

- the Online Course Development Institute from Vanderbilt University’s Center for Teaching (CFT); similar public-facing content from CFT can be on its Online Course Development Resources site

- Identifying an Effective Mechanism for Presenting New Content, Vanderbilt University, Center for Teaching, BOLD Fellows

Keep in Mind

Developing an online course is an iterative process. Just as with face-to-face courses, you will most likely need to continue to make improvements and to adjust elements to meet the needs of your students. Learn more on Page 7.

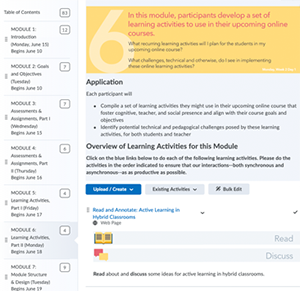

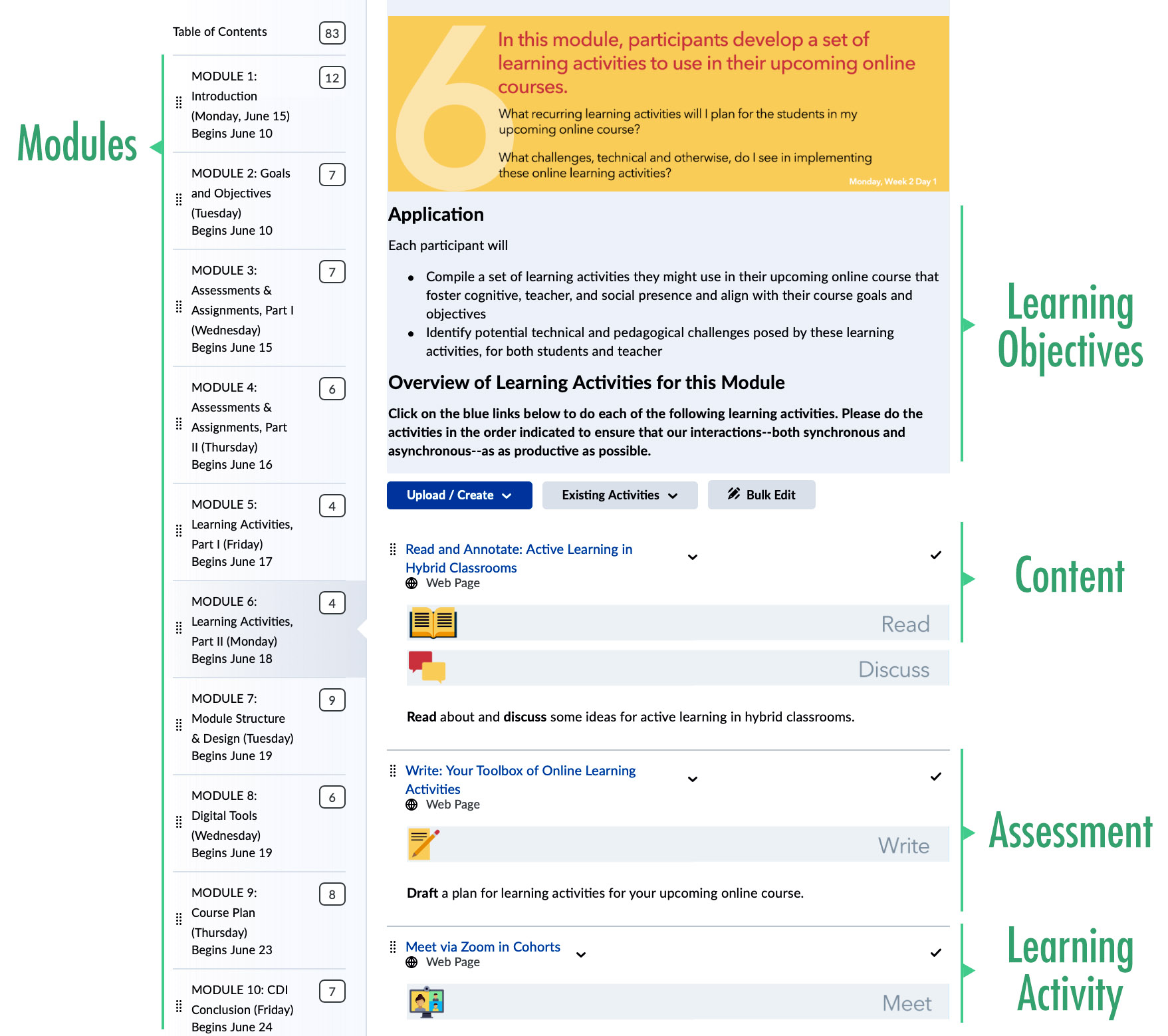

Every online course is built around a series of sequentially ordered modules (also called lessons or units) that organize class materials by topics. Each module contains the core features discussed in this resource: course goals and learning objectives, assessments, learning activities, and content. On this page, we’ll explain how to incorporate these elements into an online course structure using your LMS. Although every LMS is different, they typically have the same key features for presenting modules and their core elements. For example, the image below illustrates one module within Vanderbilt University’s Online Course Development Institute (the content from which this IRIS Module was created). The institute uses Brightspace, Vanderbilt University’s LMS of choice. Note that the module’s key features are labeled.

Source: Adapted from the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching Online Course Design Institute.

Module Structure and Design

Structuring your online learning modules requires the same sort of thoughtfulness that you apply to face-to-face lesson planning. Keep in mind that there is no one perfect module structure. Even when two different courses are designed and taught by the same person, they will typically use a somewhat different structure based on the learning goals and activities of each course.

Keep in Mind

- Ideally, your online learning environment will foster student engagement.

- Using the same series of activities with no variation day after day, module after module, will inevitably lead to boredom for you and your students.

Think about your module’s structure as the way in which the goals and objectives, assessments, learning activities, and content are laid out and organized for your students. In online teaching, a module structure that is clear and intuitive creates a similarly identifiable format for every module. Even though the content and activities change from module to module, the structure itself remains relatively consistent. This gives your students a predictable learning path. The more predictable and intuitive your module structure, the easier it is for students to navigate and to understand clearly what they are expected to do.

This predictability serves another important purpose: It helps save you time in the long run, inasmuch as students are less likely to need support. Moreover, consider making modules available only when you’re ready for students to work through them (see the open dates listed in the table of contents in the example above). This will allow you to control the pacing and keep students learning as a group, without some moving ahead and others lagging behind. Following are a few ways to provide clarity and consistency in your modules. Notice how the structure of the sample module above incorporates many of these features.

| Consistency in Structure for Online Courses | |

|

Labeling and Terminology |

|

|

Layout, Location, Navigation, and Ordering |

|

|

Scheduling |

|

|

Text, Icons, Color, and Formats |

|

Source: Adapted from the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching Online Course Design Institute.

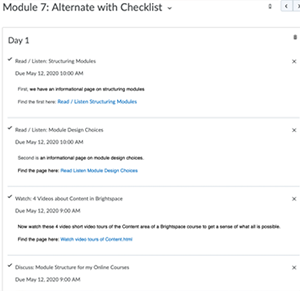

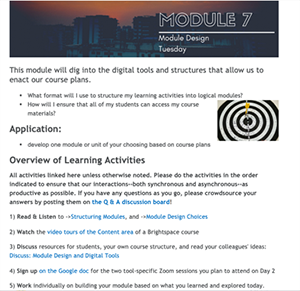

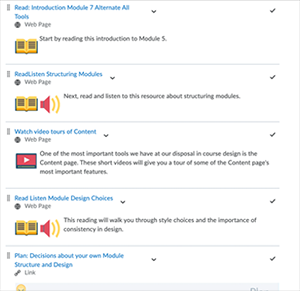

Your LMS might include the option to use a number of different module formats. If this is the case, select the one that meets your specific needs and preferred approach. Just be sure that it also offers a clear learning path for your students. For Brightspace users, some examples of other types of formats and layouts are shown below.

|

Module with Tools and Descriptions Icons, labels (e.g., Read/Listen; Watch) and descriptions or annotations provide different types of cues to learning activities.

|

Module with a Checklist Course content, learning activities, and assessments are linked within a checklist. Students check off items when completed. |

|

Module with In-Text Links All course content, activities, and assessments are linked within the text on a single page. Clicking and scrolling are reduced, though there is less room for explanations. |

Module with All Tools, No Description This design puts all of the content in the linked tools, which allows for less scrolling. However, students have to click on every link to access module information.

|

Examples courtesy of the Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching Online Course Design Institute.

Tips

- Time Requirements: Consider how long each activity will take.

- If your face-to-face course is set up for students to spend 3–5 hours a week reading and preparing and three hours per week in class, make sure you don’t inadvertently create a much higher or lower workload for an online course.

- It’s common for faculty to err on the side of creating too heavy a workload when they first move their courses online. Thoughtful planning can help prevent that.

- Text: Present text in chunks or easy-to-digest pieces that students can easily read and comprehend.

- Break text into short paragraphs.

- Make use of formatting options such as headings, bullets, and graphics.

- Incorporate roughly seven pieces of information for each module. Use the “7 plus or minus 2” instructional design rule of thumb so that you end up with between 5–9 items. Source: Identifying an Effective Mechanism for Presenting New Information

- Audio or video: Write a brief description or annotation that includes the viewing/listening time. To help maintain student attention and maximize retention:

- Limit most curated audio or video files to six minutes or less.

- Develop asynchronous video lectures in 7- to 10-minute chunks.

- Images: Whether creating design elements or using stock images or those created by others, be sure to:

- Avoid using copyrighted images or graphics.

- Add alt-text into the description area so that screen readers can appropriately describe what your images contain for students with print disabilities (e.g., dyslexia, visual impairments).

- Tools: When selecting tools to use in your course:

- Identify what you want to do first then find a tool that helps you to do it.

- Use only a few tools for each course.

- Practice using the tools before introducing them to the students.

- Provide instructions or links to “how-to” videos for each tool for students.

- Make sure tools are accessible. Source: Identifying an Effective Mechanism for Presenting New Information

A Welcoming and Supportive Environment

Once you’ve incorporated the key elements into your online course structure, you should think about how to make your students feel welcome and supported. This is especially important when students are transitioning from all face-to-face courses to all online or hybrid courses. Students may have anxiety about how they will perform in multiple online courses—each perhaps with a different structure and using different tools. To allay their fears and to let them know they can be successful in your course, there are a number of steps you can take throughout the semester.

The way that you welcome your students at the beginning of the semester is critical and sets the tone for the remainder of the course. This can reflect your own style and personality, whether via a clever or witty announcement or a warm and welcoming email. Alternately, you can include a welcome video in your LMS, whether as part of the first module or in another prominent place in the course.

Throughout the semester, maintain a welcoming environment and promote a sense of community by:

- Communicating clearly to students that you are available to address their questions or concerns

- Creating opportunities for students to connect with others in the course, especially those who have similar interests or goals

- Incorporating images, videos, and text that represent student heterogeneity

Students who are engaged are more likely to feel as though they belong to your online course community. A few examples of ways to support student engagement are included below.

At the beginning of the semester:

For Your Information

Social presence and teacher presence are the two areas of engagement that have the most significant effect on classroom climate.

- Provide an orientation to the course (print or video) to familiarize students with the course features (e.g., LMS layout, course structure, types of learning activities and assessments).

- Find creative ways for students to introduce themselves (e.g., ask students to create a personal video; post a picture of where they’re from and another of where they’d like to be; use icebreaker activities).

- In your syllabus, explicitly communicate policies and expectations (e.g., appropriate discussion board rules and etiquette, attendance).

- Describe expectations for student engagement and reflection (e.g., post to discussion board at least once per week).

Throughout the semester:

- Use a variety of learning activities and assessments to engage students with the course content in meaningful ways.

- Use discussion boards as a way for students to reflect on their own learning and expose them to the viewpoints and perspectives of others through peer-to-peer and peer-to-instructor interactions. Additionally, make sure to monitor the posts to ensure adherence to the established guidelines to maintain a safe online community and correct any misperceptions.

- Continue including both small- and large-group activities throughout the semester to maintain social presence and a sense of community.

Digging Deeper

![]()

UDL

- Ten Steps Toward Universal Design of Online Courses University of Arkansas, Little Rock

- UDL on Campus The Center for Applied Special Technology (CAST)

Note: CAST has developed a collection of resources for those working in post-secondary institutions. This site includes sections on UDL in higher education, course design, media and materials, and accessibility and policy.

Accessibility

- 20 Tips for Teaching an Accessible Online Course University of Washington

- Accessible Teaching in the Time of COVID-19 Vanderbilt University, Critical Design Lab, Mapping Access Project

- Designing an Accessible Online Course University of Arkansas, Partners for Inclusive Communities

- Accessibility for Online Courses Indiana University/UC Davis

Students in your course will reflect a many backgrounds and academic abilities. There are some considerations and steps that you can take in your planning and course design to support an equitable experience for all your students.

As we discussed previously, you are required to provide accommodations for students with disabilities in your course(s). However, it is possible to reduce the need in general for accommodations in your classroom by making design choices that are more inclusive from the beginning.

Good course design reduces barriers to learning so that ALL students can access your online courses. As you build your modules and make design choices, try to approach that work from the perspective of Universal Design for Learning (UDL), which addresses engagement, representation, and action and expression. When you incorporate UDL, try to anticipate the learning differences and preferences that your students will bring to the course and then provide options to address those differences. Employing the UDL guidelines can lead to better access to and connection with the course content. You might:

- Present information in a variety of ways (representation).

- Allow students options for learning and demonstrating their knowledge (action and expression).

- Incorporate practices that maximize student interaction and involvement (engagement).

Example

Here’s how this might look across the span of a unit or module:

- Provide multiple means for representation: Present content in multiple ways: articles, a textbook chapter, a video documentary, and audio interviews with experts. Ensure that accessibility features (e.g., captions for the video, transcripts for the audios) are included.

- Provide multiple methods for action and expression: Use a variety of methods—like discussion boards and small-group discussions and activities—to allow students to explore their own and others’ viewpoints. Offer summative assessment options for the unit that include a paper, a video project, or a traditional online test.

- Provide multiple options for engagement: Allow discussion board entries to be posted using students’ preferred method (e.g., writing, audio, video).

As you design your course, also consider whether all students will have the resources they need to participate fully in the class (e.g., access to the Internet, technology). Also, consider whether they will likely have difficulty using unfamiliar technology or tools. Encourage your students to share any issues they may encounter. As you think about these issues, try to find alternate ways for your students to participate or to access the resources they need. For example, if students do not have reliable Internet access, provide the content they need in an alternate format (e.g., reducing the size of files for videos).

Listen as Joe Bandy and Adriane Seiffert discuss technology access challenges and suggestions for ways that faculty can provide support.

Joe Bandy, PhD

Assistant Director, Center for Teaching

Vanderbilt University

Factors that create access challenges (time: 1:20)

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Senior Lecturer and Research Assistant

Professor of Psychology, Vanderbilt University

Examples of access challenges (time: 1:46)

Joe Bandy, PhD

Factors that create access challenges

It’s one of the largest challenges of teaching online since it reveals many of the inequalities our students experience in their homes, in their communities, which we often don’t see in face-to-face learning environments. Some students have great connectivity, technology, and access, while others simply do not. In the spring, I had students who were engaging fully in the course, face-to-face. But when they went home, a couple of them were in rural areas with really bad connectivity and were having to use cell phones with very spotty connections to try to do all the writing for the course and connect with discussion boards, much less the synchronous zoom sessions that we were holding. Because of structural disadvantages in our society, there is a whole other category of student who haven’t developed the self-confidence or self-regulation or self-efficacy to guide themselves through an online course without a significant amount of support. They just haven’t learned in this way before. They just need a lot more guidance, a lot more communication, a lot more sense of expectations, maybe even a personal connection to their peers or to instructors. So, it presents a wide array of challenges and to address that, I think schools have to do a lot of work to equip students with the technology they need, if they can, and to support faculty development that emphasizes inclusive and equitable teaching so that instructors can do the best that they can.

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Examples of access challenges

So there are lots of issues. The student is accessing the whole class through her phone. She doesn’t have a computer, so she does everything through her phone, including writing all of her assignments. I have another student, she is a receptionist, and she does the class while she’s at work. So, we have Zoom discussions and she contributes the best she can but there’s noises going on behind her because she’s in a work environment. I had a student who had separate audio and visual channels, because the video camera worked on his laptop, but the sound didn’t work so he has to use his phone for the sound and the computer for the visual. I’ve had students who had difficulty downloading the lectures, and so I put them all on a VU Box, taking out the video component with me and just left voiceover on the slides so it’s easier for them to download. I did have a student who expressed difficulty with accessing class material because he didn’t have a safe place to be. He was accessing the course through his computer at hot spots, at different places in the country. I didn’t have a solution for him other than posting materials in a way that was easier for him to download, allowing him more flexibility with when to upload assignments and meeting with him when he could meet to work through a plan. When he got really behind, we met and talked about it and said, “Ok, well, here are the things you absolutely have to do. Here’s how you can do that with the time that you have. And here’s the likely grade you would get if you complete these.” And talking through a plan for how to do it really made a difference for him.

Joe Bandy, PhD

Four suggestions to reduce technology access challenges

The first practical bit of advice for instructors is that they focus on asynchronous activities more than they used to so that students with limited connectivity will still be able to access any number of discussion board posts or lecture content that they can download slowly in their own time and engage in a course at their own pace. That will help students with low bandwidth or lower technology resources.

Second, the core structures and communication strategies must be really clear and supportive so that students have full and multiple directions and support whenever they want to engage with tools or activities and assessments. So just throwing a syllabus online and hoping students follow it may not be sufficient for some students with lower self-regulation. They need instructions about how to use the tool. They need instructions about what the goals are and what they’re supposed to achieve, any rubrics that might help them to give guidance about the criteria by which they will be assessed. That means more e-mailing, more clear and intuitive course structures online or office hours, potentially one-on-one student conferences and reaching out to those students who might fall behind.

A third bit of advice would be to scaffold assignments so as to make sure the students are progressing in their development of autonomy and self-efficacy towards the learning goals.

Lastly, I would try to develop a culture of inclusion and equity that allows students to feel fully engaged. That can mean making course content and assignments more culturally and personally relevant to them, but also creating cultures with your students about how you all wish to help everyone in your class to thrive. That might mean opening conversation with students about what collaborative learning looks like and what type of voice that they wish to have in in their learning process. And that can actually make all students, regardless of backgrounds, feel more socially and intellectually engaged in the work of learning in the course.

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Ask questions

I haven’t really been able to help a lot of these students other than be commiserate and be supportive and try to help them solve their problems. They have to find a way to ask me the right kind of question, like, “Could you post on another website?” or “Could you describe things in a different way so I could read it rather than listening to it?” All of those sorts of things have been really helpful so I hope students continue to reach out with suggestions about what can help them.

In general, what I tried to do is to meet every student from where they are. I think that’s one of the things that faculty do already, but now we’re going to need to do it in terms of the technology as well as in terms of their ability to learn. So, asking questions like: What device are you using? How is your Internet connection? Is it reliable or not? What other factors are going to keep you from working on class now? Are you going to need to travel sometime in the coming future and how are you going to schedule that in with your other responsibilities? All of those are going to be things that I’m going to start talking to my students about in the fall and I expect will be important for everybody to consider.

You also need to take time to think about potential learning barriers in your course design. Some of the course design features that you already use for accessibility purposes will also support this. For example, captions on videos are not only helpful for students with hearing impairments (accommodations) and those who like to have text that reinforces auditory information (learning preference, engagement) but also improve access for students who are English learners. Finally, explore your own preferences and consider how these might be reflected in your teaching behaviors. For example, make sure that your course materials reflect a variety of viewpoints and perspectives, and not just those from the dominant culture. This should be reflected in everything from the readings (and their authors) to the images that enhance your presentation slides. Your preferences for certain students might be indicated in your actions: which students you call on, the way you pose questions, discrepancies in the amount of “wait time” you provide, the quality and quantity of feedback you give, among other similar considerations.

Joe Bandy discusses these considerations in more detail (time: 2:45).

Joe Bandy, PhD

I think a first step for any instructor is to really start to examine how they approach the content of their course and their students, and to examine any biases or limitations that they might impose on how they interact with the content or with students. If we don’t do that, then we can sometimes erect barriers and have difficulty connecting with our students and where they are. Second, I think it’s really important to get to know our students, learn what makes them motivated, and help them to thrive in our courses. You can do that in the form of background knowledge surveys, or one-on-one meetings earlier in the semester, or assignments that might be more, say, autobiographical. If you have the opportunity to do that in a social science or history class or something like that, that can allow you to personalize assignments and help students select, you know, a relevant paper, discussion contents that are motivating and engaging for them. Certainly when it comes to content and how and who can access it, I would suggest all video conferencing and lecture capture have closed captioning, and make sure that all of the posting that one does in a learning management system be intuitively well-structured so that there is good guidance throughout. All of that can be good not only just for those who might have various disabilities, but also English language learners and any number of others who just might not be familiar with the course structure or content. When it comes to the readings, assignments, and activities, I would really try to ensure that all of them have diverse voices included, not merely the voices who are already well-represented in our society. If students aren’t able to see people like themselves in the course readings or examples or case studies that are used in a course, then it can be difficult for them to see the course or the subject matter as relevant or even meant for them. So, using examples, for instance, in a science class or statistics class that focus on sports—that’s going to be exclusive to women students potentially, or anybody who is less of a sports fan. Citing scientists who are exclusively white men may subtly teach women students, and students of color that they really have no place in science, potentially. And maybe they are distracted, and stereotype threat grows where they believe they can’t perform in the class. The cognitive load thus goes up and their performance actually diminishes. These kinds of things are common in the research on difference and education. But we, as instructors, can do a lot to mitigate them by being attentive to differences, trying to address them and our own biases, and coming up with assignments, whether it’s online or face-to -face, that are all inclusive.

We have discussed the importance of building a community of learners. Listen as Adriane Seiffert shares her thoughts on this topic, how she was able to do this during her summer course, and her thoughts for doing so with a class of 90 students in the fall.

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Senior Lecturer and Research

Assistant Professor of Psychology

Vanderbilt University

Creating a class versus designing a course (time: 1:52)

Creating a class with 90 students (time: 1:23)

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Creating a class versus designing a course

I think my biggest “aha” moment came when I thought, “A class is not a course.” A class is a group of people that all get together to learn together. A class is that social facilitation you get from knowing someone else is doing what you’re doing and going through what you’re going through. That you are moving along the path, watching each other as you get experience with this new material, this new device, this new way of thinking. And learning as much from the changes in your experiences, you learn from observing other people. And the class component is so much what education is that I wanted it a part of how I was teaching, even if I was teaching online. So while I could spend many hours designing my course in terms of the content and the types of activities, I also needed to make that class. I needed to make that group of people who was going to go through this together and forge those relationships and make sure that social facilitation happened.

Well, one way was to set up this near synchronous course design so that students know that when they log into the Zoom, everybody else is going to be there and they’re all gonna go watch the videos together. They’re all going to do the activities together. And so there is that social pressure to get it done because everyone else is doing it at the same time and that they can come back and talk about it and really experience it unfolding together. Another thing is to meet with the students individually and make sure that they have access and have resolved their problems or their concerns about the course in terms of getting the content and using the tools that we were using.

Adriane E. Seiffert, PhD

Creating a class with 90 students

A class of over 90 students is a lot of students. And for those of us who are used to teaching large courses, there is a rhythm to it that you get used to in a large room. And I expect that all of that is going to disappear when I’m delivering lectures as recorded or over Zoom. So I’m going to have to find another way of making that community that isn’t going to be available in that physical space. One of the things that encourages me is that these young students are really great at that. You know, when I was their age, we watched television and played outside. We didn’t have nearly the number of tools that they have already for connecting with each other online, right? They all are used to making social connections online. So this is not going to be as hard for them as maybe it is hard for me. So I’m going to see what we can do together. I’m going to see where they can find niches to build their own communities. I’ll put them into groups and I’ll give them tasks. But I’m going to see what they can come up with to make that sense of people working together and having that class experience that I’ve talked about.

Tools for Designing a Course

The table below includes links to informational guides and videos for several common learning management systems to help you design your course.

| LMS | Links to Informational Guides and Videos |

|

Brightspace |

|

|

Canvas |

|

|

Blackboard |

|

|

Moodle |