Why should students with significant cognitive disabilities be included in general education classrooms?

Page 1: Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities

Students identified with significant cognitive disabilities have one or more disabilities that significantly affect their intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior (e.g., social skills, activities of daily living). These students require intensive, individualized instruction and supports. You may also hear these students referred to as having extensive support needs or low incidence disabilities—that is, those disabilities that occur in low numbers.

Students identified with significant cognitive disabilities have one or more disabilities that significantly affect their intellectual functioning and adaptive behavior (e.g., social skills, activities of daily living). These students require intensive, individualized instruction and supports. You may also hear these students referred to as having extensive support needs or low incidence disabilities—that is, those disabilities that occur in low numbers.

intellectual functioning

The actual performance of tasks believed to represent intelligence, such as observing, problem solving, and communicating.

adaptive behavior

The performance of the everyday life skills expected of adults, including communication, self-care, social skills, home living, leisure, and self-direction.

The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) includes 13 disability categories under which students can qualify for special education services. Although significant cognitive disability is not one of the 13 IDEA categories, students most often qualify under the categories of intellectual disability, autism, multiple disabilities, or deaf-blindness.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Name given in 1990 to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) and used for all reauthorizations of the law that guarantees students with disabilities the right to a free appropriate education in the least-restrictive environment.

13 disability categories

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act lists 13 different disability categories under which three- through 21-year-olds are eligible for services. These categories are:

- autism

- deaf-blindness

- deafness

- emotional disturbance

- hearing impairment

- intellectual disability

- multiple disabilities

- orthopedic impairment

- other health impairment

- specific learning disability

- speech or language impairment

- traumatic brain injury

- visual impairment (including blindness)

It is sometimes difficult to identify a student’s specific disability, particularly in the case of young children. In such instances, federal law allows states to serve these children under the category of developmental delay—a term used to encompass a variety of disabilities in infants and young children, indicating that they are significantly behind the norm for development in one or more areas, including motor development, socialization, independent functioning, cognitive development, or communication.

(Close this panel)

Did You Know?

Just like any other group of students, those with significant cognitive disabilities display a range of characteristics and needs. Many have complex communication needs or co-occurring motor or sensory disabilities. It is estimated that:

- 25-37% do not use oral speech

- 7-12% use a wheelchair or other mobility device

- 7-10% are blind or have low vision

- 4-8% are deaf or hard of hearing

(Erickson & Geist, 2016)

Students with all kinds of disabilities are often educated for at least part of the school day in general education settings. The decisions regarding how much time they spend and what they learn in the general education classroom occur through an intensive process and involve an entire team of professionals and the student’s family. To meet these students’ needs in the general education classroom, the general education teacher collaborates with many individuals, including the special educator.

For Your Information

Students with disabilities might receive services and supports across a combination of settings (e.g., general education classroom, special education classroom). Further, the setting in which a student receives services can change over time based on a student’s progress or needs.

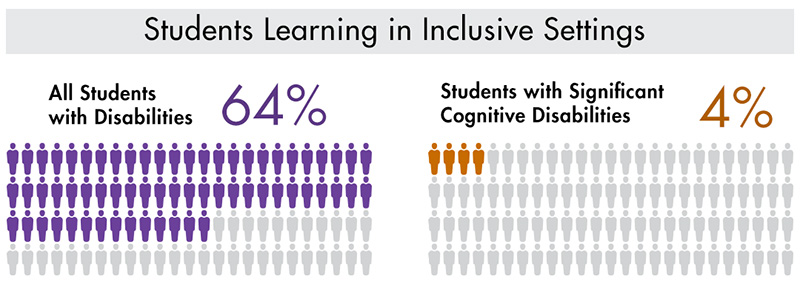

When compared to peers with other disabilities such as learning disabilities or ADHD, students with significant cognitive disabilities are far less likely to be educated in classrooms alongside grade-level peers without disabilities. Instead, the majority of these students receive most or all of their instruction in separate special education classrooms or in schools serving only students with disabilities. As of the 2018-19 school year, 64% of all students with disabilities were educated in general education settings (i.e., spending 80% or more of the school day in a general education classroom). However, in that same year, only 4% of students with significant cognitive disabilities received the majority of their instruction in general education classrooms. That means that 96% of these students spent most of their school day in a separate special education classroom, a separate school, or a home, hospital, or residential setting.

Sources: Burnes & Clark, 2021; U.S. Department of Education, 2021

However, we know that inclusion—the practice of educating students with disabilities in the general education classroom using a variety of individualized services and supports—can benefit all learners. Students with disabilities who are educated in general education environments not only have greater access to the grade-level content and curriculum, but they also have more opportunities to build relationships with their classmates both with and without disabilities. At the same time, students without disabilities may show reduction in negative perceptions (e.g., fear, hostility, prejudice) and develop understanding and acceptance of others different from themselves. Additionally, they may experience greater academic engagement and achievement due to the use of effective instructional practices (e.g., differentiated instruction, peer tutoring).

differentiated instruction

An approach whereby teachers adjust their curriculum and instruction to maximize the learning of all students: average learners, English learners, struggling students, students with learning disabilities, and gifted and talented students; not a single strategy but rather a framework that teachers can use to implement a variety of strategies, many of which are evidence-based.

peer tutoring

In special education, a cooperative learning strategy that pairs a student with disabilities with a non-disabled student; either student may adopt the role of teacher or learner.

Research Shows

Students with significant cognitive disabilities who are educated in general education settings achieve greater success in the areas of:

- Academic outcomes (Bowman et al., 2020; Jimenez & Kamei, 2015; Hudson et al., 2013)

- Social skills (Asmus et al., 2017; Fisher & Meyer, 2002)

- Communication (Kleinert et al., 2019; Buckley et al., 2006)

- Peer engagement (Brock et al., 2017; Carter et al., 2016)

- Positive behavior (Loman et al., 2018)

- Post-secondary outcomes (Mazzotti et al., 2021; Test et al., 2009)

In this interview, Diane Ryndak explains why it is important for students with significant cognitive disabilities to receive their education in general education settings.

Diane Ryndak, PhD

TIES, Principal Investigator

University of North Carolina, Greensboro

Transcript: Diane Ryndak, PhD

For decades, our field has been committed to improving the quality of life for individuals with significant cognitive disabilities, both when they are students and when they become adults. With this goal in mind, we focus on increasing their opportunities to learn and ability to be engaged in all activities in their current and future communities. For students, this means age and grade level communities, and for adults, this means society at-large. To increase their capacity to engage in activities we focus educational services on two areas: First, we focus on increasing their knowledge and skills in academics, social interactions and relationships, and post school life in their community. Second, we focus on assisting in the development of relationships that can lead to a strong and extensive natural support network. If you think about it, these are the same two areas on which we all rely every day — our knowledge base and our relationships and natural support networks. When we think about this further, we realize that our own relationships and natural support networks were developed through our interactions with people and our engagement in activities with them. These mutual experiences during our school years allowed us not only to develop knowledge and skills, but also to develop relationships that over time sustain us as contributing and valued members of our school and home communities. Research has shown us that students with significant cognitive disabilities have improved outcomes in both of these areas when they receive instruction with their age and grade level classmates in general education classes. While this requires us, the adults, to rethink our roles and commit to collaborating with each other, research tells us that this leads to the outcomes to which we all aspire for all general education students—both with and without IEPs.

The remainder of this module will help you prepare for including students with significant cognitive disabilities in general education classrooms. Specifically, you will explore the following topics:

- Inclusion in policy and practice

- General education curriculum access

- Goals, services, and supports

- Collaborative practices

- Addressing instructional needs

- Addressing communication needs