Why should students with significant cognitive disabilities be included in general education classrooms?

Page 2: Inclusion in Policy and Practice

Although it is important for students with disabilities to be physically present in the general education classroom, the concept of meaningful inclusion goes much deeper. In broad terms, inclusion encompasses the fundamental belief that everyone has a right to equal opportunities and resources. In education, this means that students with any and all disabilities are valued and viewed as contributing members of their schools and general education classrooms. For the purpose of this module, inclusion is framed as the ongoing commitment to work for the valued membership, active participation, and learning of each student with their age- or grade-level peers, utilizing a wide array of school and community structures, practices, and supports. Further, inclusion affords the opportunity for every student to achieve high expectations while building meaningful relationships in the school community. Inclusive educators embrace the following core values.

Although it is important for students with disabilities to be physically present in the general education classroom, the concept of meaningful inclusion goes much deeper. In broad terms, inclusion encompasses the fundamental belief that everyone has a right to equal opportunities and resources. In education, this means that students with any and all disabilities are valued and viewed as contributing members of their schools and general education classrooms. For the purpose of this module, inclusion is framed as the ongoing commitment to work for the valued membership, active participation, and learning of each student with their age- or grade-level peers, utilizing a wide array of school and community structures, practices, and supports. Further, inclusion affords the opportunity for every student to achieve high expectations while building meaningful relationships in the school community. Inclusive educators embrace the following core values.

| Core Value | Definition |

|

Each and every student is valued and contributes to their school community and general education classrooms. |

|

Each and every student deserves meaningful and sustained access to the academic and social environment of general education classrooms. |

|

Each and every student is a capable learner deserving of instruction that reflects high expectations and assures learning. |

|

Inclusive education requires the shared engagement and combined skills of many people. |

Source: Adapted from TIES Center Core Values.

What the Law Says

Federal law in special education upholds the values of inclusion. IDEA guarantees students with disabilities the right to a free appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE). Both of these principles reflect a strong preference for inclusion and an emphasis on setting high expectations.

free appropriate public education (FAPE)

One of IDEA’s six guiding principles; ensures that each eligible student with a disability receives an individualized education that meets his or her unique needs and is provided in conformity with the student’s IEP at no cost to the child or family.

least restrictive environment (LRE)

One of IDEA’s six guiding principles; requires that students with disabilities be educated with their non-disabled peers to the greatest appropriate extent.

Under IDEA’s provisions, FAPE guarantees services and supports designed to meet a student’s individualized needs. Additionally, FAPE ensures that students have access to the general education curriculum—the same curriculum that is used with students who do not have disabilities—alongside their same-age peers in the school they would attend if they did not have a disability. FAPE is delivered through the development and implementation of an individualized education program (IEP). This written plan is developed by the IEP team—a team of professionals, the student’s family, and the student (when applicable)— and must be designed to enable the student to:

- Make progress toward individualized academic and/or functional goals (e.g., social skills, communication, daily living skills)

- Access and make progress in the general education curriculum, as well as to participate in extracurricular and other nonacademic activities

- Take part in these activities with other students, both with and without disabilities

general education curriculum

A sequence of instruction or program of study that is aligned with grade-level content standards and is provided to all students.

individualized education program (IEP)

A written plan, required by IDEA and used to delineate an individual student’s current level of development and his or her learning goals, as well as to specify any accommodations, modifications, and related services that a student might need to attend school and maximize his or her learning.

For Your Information

An IEP team consists of a group of family members (including the student, when appropriate), educators, and other professionals who possess knowledge and expertise relevant to an individual student’s needs. Every team member should be an active participant in the decision-making process. By advocating for the student, sharing their perspectives, and collaborating effectively, the team can develop meaningful and inclusive programs where students are adequately supported to experience success in the general education classroom. For more information about the IEP team’s required members, view the following IRIS handout:

Did You Know?

The IEP team is responsible for determining a student’s LRE. When making decisions about settings and services, the IEP team can consider factors such as individual needs, family preferences, expected benefits to the student, effect on peers, and necessary supports in each setting.

However, a student may not be placed into a separate special education setting based solely on:

- The category of his disability

- The severity of his disability

- Availability of space

- Availability of personnel

- Administrative convenience

FAPE is meant to be provided alongside peers without disabilities in the general education setting to the greatest extent possible (i.e., in the LRE). When deciding where a student will receive special education services and supports, the IEP team should first make an effort to place—and maintain—the student in the general education setting. The law makes it clear that students should only be removed from the general education classroom if the IEP team determines that learning cannot be achieved, even with the use of supplementary aids and services (e.g., specialized equipment or materials, modified assignments, staff training).

For more information on least restrictive environment, including a sample process for determining a student’s LRE, view the following IRIS resource:

High Expectations

Setting and upholding high expectations for all students is frequently emphasized as a key part of providing FAPE in the LRE. The law states:

Almost 30 years of research and experience has demonstrated that the education of children with disabilities can be made more effective by having high expectations for such children and ensuring their access to the general education curriculum in the regular classroom, to the maximum extent possible.

When students with disabilities are held to high expectations, they are more likely to make progress and, ultimately, to succeed. In contrast, low expectations can lead to less-challenging instruction that limits the ability of students to reach their full potential. Teachers can use the principles and practices outlined below to maintain high expectations for all students.

Presuming competence means assuming that every student—regardless of disability label, IQ score, or perceived limitations—has the capacity to understand, learn, and make progress. Rather than focusing on what a student cannot do, educators who presume competence emphasize how the student can be successful when given appropriate supports.

All students must be able to access the same rigorous grade-level content and instruction. A flexible approach to teaching can ensure that all students are able to engage in instruction, access information, and show what they’ve learned. Individualized supports, including accommodations and modifications, will be needed for some students, but the content and materials should be as similar as possible to that of other students in the class.

accommodation

An adaptation or change to educational environments, materials, or practices designed to help students overcome the challenges presented by their disabilities and to allow them to access the same instructional opportunities as students without disabilities. An accommodation does not change the expectations for learning or reduce the requirements of the task.

modification

Any of a number of services or supports that allow a student to access the general education curriculum in a way that fundamentally alters the content or curricular expectations in question .

Equity vs. Equality

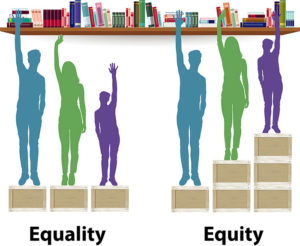

It is a common misconception that accommodations create an unfair advantage for students with disabilities. In truth, the supports offered by accommodations allow students with disabilities to access the same instructional opportunities as students without disabilities, thereby leveling the playing field. When educators use accommodations appropriately, they provide equity—that is, they give each student what he or she needs to successfully complete a given learning task or assignment. By promoting equity, teachers can break down the barriers that interfere with students’ opportunities to access learning. With the best of intentions, educators often strive to promote equality—giving every student precisely the same thing. However, by doing so, educators inadvertently limit the opportunities of students with disabilities to access learning. In other words, giving every student precisely the same thing does not ensure fairness or equal opportunity. To better understand the concepts of equality versus equity, view the illustration to the right.

It is a common misconception that accommodations create an unfair advantage for students with disabilities. In truth, the supports offered by accommodations allow students with disabilities to access the same instructional opportunities as students without disabilities, thereby leveling the playing field. When educators use accommodations appropriately, they provide equity—that is, they give each student what he or she needs to successfully complete a given learning task or assignment. By promoting equity, teachers can break down the barriers that interfere with students’ opportunities to access learning. With the best of intentions, educators often strive to promote equality—giving every student precisely the same thing. However, by doing so, educators inadvertently limit the opportunities of students with disabilities to access learning. In other words, giving every student precisely the same thing does not ensure fairness or equal opportunity. To better understand the concepts of equality versus equity, view the illustration to the right.

Instruction should be based on a student’s age- and grade-level expectations and curriculum, even if his instructional level is determined to be on a lower grade level. For example, in an eighth-grade science class, the teacher should not have a student with a significant cognitive disability read a children’s picture book in place of the textbook chapter. Instead, she should use the eighth-grade materials and curriculum with appropriate accommodations, such as providing an audio version of the chapter and a pictorial glossary of key vocabulary.

Teachers should communicate with students with disabilities the same way they communicate with others. For instance, avoid “baby talk” or otherwise talking down to a student. If he has difficulty communicating, resist the temptation to speak for him or to pretend you understood something if you didn’t. Instead, repeat or expand on what you heard and check that you have interpreted correctly.

Students can and should be allowed to make their own choices and to exercise a level of age-appropriate control over their own lives. Teachers and other adults often make decisions for people with disabilities without their input. Providing opportunities for students to make choices and learn from their mistakes increases their independence in school and life.

In the two brief videos below, a parent and a general education teacher describe how they hold high expectations for students with significant cognitive disabilities.

Transcript: Parent

Parent: … like a barrier is just educating society and educators to present confidence because Down syndrome is worn on the face. Expectations are immediately lowered, and every child is different. And you know, my son realizes when expectations are not expected of him and they’re lowered of him and the behavior shows, his mood shows.

Interviewer: Get some learned helplessness in.

Parent: Exactly! (laughs)

Interviewer: So, tell us about, a little bit about the expectations and how you guys have had high expectations for him. And what … how do you think that has impacted his educational career?

Parent: We have high expectations of him in school and life, and he knows that and he’s proud of himself when he succeeds and you know, our past experience, he would come home saying, “Not okay, Tris.” You know? “Not okay, we don’t do that. We don’t hit.” And now he comes home and saying, “I’m so proud of you, I’m so proud of you.” So, he’s happy to go to school, he’s happy when he comes home and he’s singing the songs he learned that day. And he’s asking me how old I am and –

Interviewer: He’s making good progress.

Parent: He’s making great progress because he knows now his team and his support at school have high expectations of him. We’ve always had high expectations of him at home, and we want that reciprocated at school. So, he does – when he does succeed that he’s proud of himself.

Transcript: Teacher

Interviewer: … your experiences with educational expectations, specifically for your student with intellectual disabilities in your classroom.

Teacher: For this young man, honestly, it’s the same as any other student in my classroom. I’m trying to move them forward to the next level. I’m trying to also move him forward to the next level. It’s going to look different than maybe the student that he’s sitting next to, but as long as he’s growing and he’s learning, that’s the expectation that I have for him.

Research Shows

- When educated in inclusive classrooms, students with significant cognitive disabilities can make progress on the same academic content as their grade-level peers without disabilities.

(Ruppar et al., 2017; Heinrich et al., 2016) - High teacher and family expectations directly impact students’ post-high school outcomes in employment and independent living.

(McConnell et al., 2021; Woodman et al., 2016)

Returning to the Challenge

As you’ll recall from the Challenge, Ethan is identified as a student with a significant cognitive disability. Like many of these students, Ethan has more than one disability diagnosis—in his case, intellectual disability as well as speech and language impairments. For the last three years, Ethan has been part of the 81% of students with significant cognitive disabilities who are excluded from general education classrooms. To change this trajectory for Ethan, the educational team is ready to work together to make his inclusion a priority.

As you’ll recall from the Challenge, Ethan is identified as a student with a significant cognitive disability. Like many of these students, Ethan has more than one disability diagnosis—in his case, intellectual disability as well as speech and language impairments. For the last three years, Ethan has been part of the 81% of students with significant cognitive disabilities who are excluded from general education classrooms. To change this trajectory for Ethan, the educational team is ready to work together to make his inclusion a priority.

As you progress through this module, you will find an Inclusion Toolbox at the bottom of each page that provides additional resources from the TIES Center and the IRIS Center related to the information on the page.

This information brief examines and counters six of the most common myths about students with significant cognitive disabilities.

Creating Communities of Belonging for Students with Significant Cognitive Disabilities This series of mini-guides unpacks the 10 dimensions of belonging and provides practical examples of what it might look like when students experience each aspect of belonging. School-based teams can download a Belonging Reflection Tool to structure a collaborative conversation about their current inclusive practices and plans for improvement.

Using the Least Dangerous Assumption in Educational Decisions The theory of the “least dangerous assumption” holds that educational decisions should be based on assumptions that, if incorrect, will have the least harmful effect on student outcomes and learning. This article from the TIES Inclusive Practice Series explains the concept and presents a case study and learning activities to demonstrate high expectations based on the least dangerous assumption in practice.

This handout describes both the required and additional IEP team members and their responsibilities.

Least Restrictive Environment Information Brief This information brief summarizes the principle of least restrictive environment (LRE). It also includes a sample process for determining LRE as well as examples of how the LRE might be designated for two students. |