What do teachers need to know about students who are learning to speak English?

Page 2: Second Language Acquisition

Because English learners are expected to acquire English proficiency—and simultaneously learn all of the content knowledge required at their respective grade level—it is crucial that teachers understand the basic tenets of second language acquisition. Teachers and administrators who do not understand second language acquisition may have inappropriate expectations that result in:

Because English learners are expected to acquire English proficiency—and simultaneously learn all of the content knowledge required at their respective grade level—it is crucial that teachers understand the basic tenets of second language acquisition. Teachers and administrators who do not understand second language acquisition may have inappropriate expectations that result in:

- Inappropriate referrals to special education

- Attempts to share information in a language that English learners may not comprehend

- A failure to provide students with the supports necessary to acquire new content knowledge in English

Second language proficiency develops incrementally and varies from learner to learner. When a teacher is able to identify a student’s stage of English language proficiency, they can plan instruction to meet the language needs of that student. Click on the tabs below for more about these stages.

- Students typically maintain a silent period.

- Students observe others having conversations and listen to the ways in which words are pronounced and put together in phrases.

- Students choose to interact by pointing, gesturing, nodding, or using yes or no responses.

- Students typically are able to understand 500 receptive words but are not comfortable using them expressively.

- Students are able to understand new words taught in an understandable and meaningful way.

- Students are allowed to remain silent until they are ready to speak.

- Students are able to speak using one- or two-word phrases.

- Students are able to comprehend and use expressively a vocabulary of some 1,000 words.

- Students are capable of indicating their understanding of novel information by responding to simple questions (e.g., “Who?” or “What?”).

- Students are able to use short phrases and simple sentences.

- Students can ask questions, (e.g., “Where is the office?”) and respond to simple questions (e.g., “My dream is to become a doctor.”).

- Students have a word bank of approximately 3,000 words.

- Students often have difficulty communicating their ideas because their sentences, though longer, generally include grammar errors.

- Students have a repertoire of approximately 6,000 words.

- Students are beginning to formulate longer and more complex statements and as a result offer their thoughts and opinions more confidently.

- Students are able to request clarification.

- Students have acquired and continue to acquire content-area vocabulary.

- Students are able to fully participate in grade-level activities, with additional support as needed.

- Students are able to use English much the same as their native English-speaking peers.

Regardless of the stage of second language acquisition, a student’s oral language skills continue to develop. Oral language proficiency refers to knowledge of or use of vocabulary, grammar, and sentence structure, as well as strong comprehension skills. Research has shown that students with poor oral language proficiency struggle with academic skills such as reading fluency and reading comprehension.

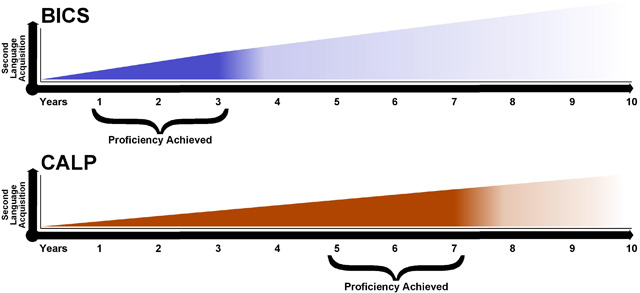

Despite this, in each of the stages of language acquisition, the student’s receptive language (i.e., understanding) is generally better than his or her expressive language (i.e., speaking). As students progress through the stages, they develop two types of language proficiency: social and academic, often referred to as BICS and CALP.

Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) refers to a student’s ability to understand basic conversational English, sometimes called social language. At this level of proficiency, students are able to understand face-to-face social interactions and can converse in everyday social contexts. These social language skills—generally acquired in approximately two years—are sufficient for early educational experiences but are inadequate for the linguistic demands of upper elementary school and beyond. Students acquire this social language by interacting with their peers, family members, and playmates. For example, Maria, who has lived in the United States for only a few months, is already able to understand her peers when they ask her in the cafeteria, “Maria, do you want to sit with us?” Maria has learned this so quickly because her peers ask her the same question every day and use physical gestures to help her to understand.

Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS) refers to a student’s ability to understand basic conversational English, sometimes called social language. At this level of proficiency, students are able to understand face-to-face social interactions and can converse in everyday social contexts. These social language skills—generally acquired in approximately two years—are sufficient for early educational experiences but are inadequate for the linguistic demands of upper elementary school and beyond. Students acquire this social language by interacting with their peers, family members, and playmates. For example, Maria, who has lived in the United States for only a few months, is already able to understand her peers when they ask her in the cafeteria, “Maria, do you want to sit with us?” Maria has learned this so quickly because her peers ask her the same question every day and use physical gestures to help her to understand.

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) refers to a student’s ability to effectively understand and use the more advanced and complex language necessary for success in academic endeavors, sometimes referred to as academic language. Students typically acquire CALP in five to seven years, a period during which they spend a significant amount of time struggling with academic concepts in the classroom. A student like Maria, who has only been in the United States for a few months, may find it difficult to understand the content-related terms (such as “photosynthesis”) discussed during science. She may also struggle with instruction-related terms such as “compare and contrast.” Finally, her difficulty might be compounded by the fact that she may not have learned these concepts in her first language.

Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP) refers to a student’s ability to effectively understand and use the more advanced and complex language necessary for success in academic endeavors, sometimes referred to as academic language. Students typically acquire CALP in five to seven years, a period during which they spend a significant amount of time struggling with academic concepts in the classroom. A student like Maria, who has only been in the United States for a few months, may find it difficult to understand the content-related terms (such as “photosynthesis”) discussed during science. She may also struggle with instruction-related terms such as “compare and contrast.” Finally, her difficulty might be compounded by the fact that she may not have learned these concepts in her first language.

Many teachers mistakenly believe that students can’t learn academic language until they have become proficient in social English. It is important to understand that BICS and CALP develop simultaneously, but the acquisition of academic language takes longer. Therefore, teachers should begin instruction in academic language as soon as possible.

For Your Information

Below are two examples of how the lack of knowledge about BICS and CALP can be detrimental to EL students:

- Some teachers inappropriately refer EL students who are performing poorly to special education.

- On the other hand, some school districts’ policies prohibit special education referrals for EL students for five to seven years, based on CALP development.

In the first instance, students struggling because of a language issue need to receive appropriate language support services (e.g., ESL, bilingual education), not special education services. Conversely, in the second example, delaying special education referrals for EL students who qualify could prove detrimental to their academic success. School personnel should be knowledgeable about second language acquisition and special education and should provide services accordingly.

Below, Janette Klingner suggests that some social conversations can be just as cognitively demanding as academic ones (time: 1:29).

Janette Klingner, PhD

School of Education

University of Colorado, Boulder

Transcript: Janette Klingner, PhD

There are those who challenge the idea of social language being undemanding, that social situations where we are talking with others are cognitively undemanding. I think, rightfully so, that some social situations are actually very challenging and can be cognitively demanding when students don’t have the pragmatic skills they need in order to make sense of social cues. So I think we have to be careful not to think of all social language as being cognitively undemanding and academic conversations or language being cognitively demanding. That would be too simplistic of a way to think about it. Some social language situations—you can imagine a meeting or a situation where you’re sitting around a table with a group of people grappling with a difficult problem where the social cues that you pick up on are actually very important for enabling you to participate and make sense of the conversation. And you actually have to use higher-level thinking skills. It’s not just a matter of distinguishing between what Cummins refers to as BICS, or basic interpersonal communication skills, which he would consider a little easier to acquire, or CALP, what we call Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency, which is more demanding. Really, both can be.

Activity

Watch the video of an EL student and her teacher and determine whether the student is demonstrating BICS (social language) or CALP (academic language) (time: 2:23).

Transcript: BICS or CALP?

Teacher: Where are you from?

Student: Honduras. Where are you from?

Teacher: I’m from California. How long have you lived here?

Student: Two years.

Teacher: Yeah?

Student: And you?

Teacher: Um, I’ve lived here for four years. Almost four years, yeah. You like it here?

Student: Yes.

Teacher: Yeah? What do you like about it?

Student: People are nice, and I have a lot a lot of friends here. I especially like the food here.

Teacher: Oh, yeah? What kind of food?

Student: Hamburgers and pizza.

Teacher: Oh, pizza. I like pizza, too. What kind of food do you eat in Honduras?

Student: We eat a lot of food, but mostly I like the eggs and the beans and the cheese.

Teacher: Ah, do you eat that food here, too?

Student: Yeah. Sometimes my mom makes them.

Teacher: Ah, what’s the your favorite food that your mom makes?

Student: Spaghetti.

Teacher: Oh, yeah, I love spaghetti. Do you like to cook? Do you help your mom in the kitchen?

Student: Yes.

Teacher: Yeah? What do you do when you help her?

Student: I just sometimes…she goes to the store with me and buys some of the things that she’s going to do for the food.

Teacher: Oh, so you help her with the groceries?

Student: Yes.

Teacher: We’ve been learning about where plants get their energy from, so how are the roots important to a plant?

Student: The roots are where a plant takes in the water of the plant. They help the plants grow more if they’re from the sun.

Teacher: Okay, and how are stems important to a plant?

Student: They’re important to plants so they can get sun, water, and some other things.

Teacher: How do the green leaves of the plant make sugar?

Student: When the water falls into the leaves, in the…what’s it called? When the water falls into the leaves, in the…in the leaves.

Which of the below best describes the student’s language proficiency?

- Participate in social conversations on familiar topics with her teacher.

- Ask and answer questions with her teacher.

- Make herself understood by using consistent standard English grammatical forms.

- Provide complete information about grade-level content previously presented (e.g., how green leaves make sugar).

- Recall the content-related vocabulary that she has been taught.

- Demonstrate an advanced level of language development.