What specific strategies can improve outcomes for these children?

Page 4: Early Childhood: Focused Interventions

In addition to the foundational strategies that have been shown to be effective for all students with ASD (i.e., reinforcement, modeling, prompting, time delay), a number of other focused strategies targeting discrete skills or behaviors have also proven effective among young children. Due to advancements in the area of diagnostics, it is now possible to reliably identify children with ASD as early as 24 months. The early childhood years, especially birth to age five, are critical in terms of cognitive and social communication development, and therefore strategies that are appropriate for children with autism should be implemented as soon as the team suspects that the child has ASD.

In addition to the foundational strategies that have been shown to be effective for all students with ASD (i.e., reinforcement, modeling, prompting, time delay), a number of other focused strategies targeting discrete skills or behaviors have also proven effective among young children. Due to advancements in the area of diagnostics, it is now possible to reliably identify children with ASD as early as 24 months. The early childhood years, especially birth to age five, are critical in terms of cognitive and social communication development, and therefore strategies that are appropriate for children with autism should be implemented as soon as the team suspects that the child has ASD.

Listen as Wendy Stone discusses this in more depth.

Wendy Stone, PhD

Professor, Educational Psychology

Director of the Research in Early Autism Detection and Intervention Lab

University of Washington

(time: 2:09)

Transcript: Wendy Stone, PhD

Early diagnosis is critical for children with autism for lots of reasons. We know from developmental neuroscience and other cognitive sciences that there’s rapid brain development that goes on in the early years, and during that time what we want to do is to form connections that are going to be useful for the child’s learning and that are going to prepare that brain for the incoming information that they’re going to get in the next lifetime of experiences. What we think happens when we intervene early is that we’re actually changing the architecture of the brain, and we’re changing those connections into more productive alignment with future learning. In autism, there is a great deal of research now indicating that early intervention can increase skills and abilities in all areas: in language, in social interaction, in behavior, in cognitive and developmental skills. The outcomes are very diverse, and we’ve learned that the core deficit areas, skills, or impairments of autism actually seem to be malleable, and that’s very exciting, and it’s very hopeful and encouraging. So we want as many children as possible to begin receiving early autism specialized services at very young ages.

The most unfortunate aspect of that is in many places until the child has a formal diagnosis of autism, they can’t receive the autism specialized services. Teachers should know that because there can be a very long wait between screening or between concerns and diagnosis, they should definitely consider using strategies that are appropriate for children with autism in the meantime. You don’t really need to wait for a definitive diagnosis when you’re working with a child who has severe social communicative impairment. The strategies that are used with children with autism would be very appropriate during this waiting period.

Many young children with ASD have delays in acquiring receptive and expressive language skills, as well as the non-verbal forms of communication that emerge in infancy. These are precursors to language and are important for expressing needs and desires. When children and students are unable to express themselves, they can often become frustrated, which might result in inappropriate behaviors such as throwing a tantrum or becoming aggressive. To avoid this, these skills often need to be taught explicitly so that young children can understand the world around them and express their wants, needs, and desires. This page will explore two communication strategies: visual supports and Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS).

Visual Supports

Visual supports refer to any type of visual item (e.g., photographs, picture symbols, written words, clipart, line drawings, physical objects) that helps a student understand behavioral expectations and independently perform a skill or behavior. These supports are often used in early childhood settings with typically developing children. For example, the rules poster is illustrated with pictures of children engaging in appropriate behaviors, and as illustrated in the photos below, common objects are labeled with words (e.g., chair, table) and toy bins or shelves contain a picture of what belongs in that space.

For Your Information

We all use visual supports, such as sticky notes on desks or refrigerators, to remind us to complete certain tasks. Therefore, it should come as no surprise that visual supports are not just effective for typically developing young children or those with ASD. Research indicates that they are effective for children and youth with ASD from 3–22 years of age. Although described on this page, visual supports should be considered for use across all age groups.

When teachers work with students with ASD, visual supports can be used to improve a number of outcomes, including social, communication, behavior, school readiness, play, and cognitive. Visual supports also help students with poor receptive language skills understand what is expected of them, where to go, what to do, how long activities will last, and so forth. The types of visual support teacher use will depend on the behavior or target skill being addressed. Once determined, the teacher can provide one or more of the types of visual supports described below.

This type of visual support designates special areas in the classroom where given activities occur (e.g., home living, circle time). This helps children learn which activities/behavioral expectations are expected in different areas, as well as where they are expected to be/remain for the duration. Teachers can create boundaries in a number of ways: rugs, furniture arrangement, and tape on the floor.

This type of visual support designates special areas in the classroom where given activities occur (e.g., home living, circle time). This helps children learn which activities/behavioral expectations are expected in different areas, as well as where they are expected to be/remain for the duration. Teachers can create boundaries in a number of ways: rugs, furniture arrangement, and tape on the floor.

Because children with ASD often have difficulty understanding the language and non-verbal cues of others, they frequently benefit from visual cues. These supports can include a graphic organizer, a communication board, picture or text labels, and picture instructions. They can be created with multiple media, such as photos, illustrations, symbols, text, and objects, but it is important to know that some children with autism might respond better to simple illustrations (e.g., line drawings), which contain fewer visual distractions than do photographs or complex illustrations.

Because children with ASD often have difficulty understanding the language and non-verbal cues of others, they frequently benefit from visual cues. These supports can include a graphic organizer, a communication board, picture or text labels, and picture instructions. They can be created with multiple media, such as photos, illustrations, symbols, text, and objects, but it is important to know that some children with autism might respond better to simple illustrations (e.g., line drawings), which contain fewer visual distractions than do photographs or complex illustrations.

graphic organizer

glossary

communication board

glossary

Source: The Picture Communications Symbols ⓒ1981-2014 by Mayer-Johnson LLC. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Used with permission.

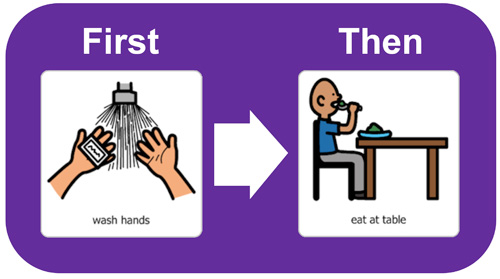

These supports, which can include any of the visual cues above, help children predict what activity will come next. An example of a simple visual schedule is a first-then board, which visually presents what the child or student needs to do now (first) and what he or she will do next (then). First-then boards are used to illustrate a short sequence for performing a task. Often, the sequence consists of a less desired task followed by a preferred one. A more detailed schedule can indicate the day’s activities, which helps children understand when to expect different events, or the steps in a multi-step activity (e.g., getting ready for school) to help them stay on task. Typically, children and students with ASD prefer predictability, and these supports can help alleviate the stress and anxiety that results from not knowing what will occur in the future or what to do next.

These supports, which can include any of the visual cues above, help children predict what activity will come next. An example of a simple visual schedule is a first-then board, which visually presents what the child or student needs to do now (first) and what he or she will do next (then). First-then boards are used to illustrate a short sequence for performing a task. Often, the sequence consists of a less desired task followed by a preferred one. A more detailed schedule can indicate the day’s activities, which helps children understand when to expect different events, or the steps in a multi-step activity (e.g., getting ready for school) to help them stay on task. Typically, children and students with ASD prefer predictability, and these supports can help alleviate the stress and anxiety that results from not knowing what will occur in the future or what to do next.

Source: The Picture Communication Symbols © 1981-2015 by Mayer-Johnson LLC. All Rights Reserved Worldwide. Used with permission.

Picture Exchange Communication System (PECS)TM

For Your Information

Research indicates that PECS is effective for children and youth with ASD from 3–14 years of age.PECS is a type of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) in which children and youth with limited verbal skills learn to communicate and interact with others through the exchange or presentation of visual cues (i.e., a picture or symbol). Recall that David from the Challenge is non-verbal and cannot effectively express his wants and needs. He has recently been introduced to PECS. Teaching children to use PECS involves a six-phase process.

augmentative and alternative communication (AAC)

glossary

| PECS: Six-Phase Process | |

|---|---|

| Phase 1: How To Communicate |

The child learns how to pick up a picture symbol and exchange it for a desired item or activity. |

| Phase 2: Distance and Persistence |

The child learns to generalize and maintain his actions in a variety of natural settings and with different communication partners (e.g., parents, siblings, teachers, peers). |

| Phase 3: Picture Discrimination |

The child learns to choose from two or more picture symbols to request a desired item or activity. |

| Phase 4: Sentence Structure |

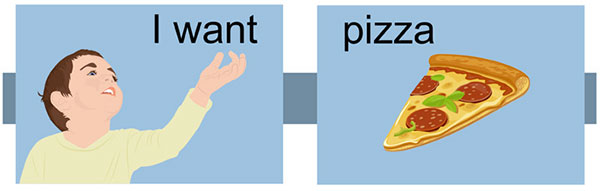

The child learns how to ask for an item or activity by constructing a simple sentence out of picture symbols—often referred to as a sentence strip. For example, the child could use the “I want” and “pizza” symbols to request a slice of pizza. The child will later learn to build more complex sentences using picture symbol cards that represent adjectives, verbs, and prepositions.

|

| Phase 5: Answering Questions |

The child learns to respond to the question “What do you want?” by creating a sentence using a picture symbol for “I want” combined with a picture of the desired item or activity. |

| Phase 6: Commenting |

The child learns to answer questions such as “What do you see?” by creating a sentence strip with symbols representing “I see” and an item. Later, the child is encouraged to initiate conversations using the sentence strips. |

Because of the highly structured nature in which this strategy should be taught, it is recommended that teachers interested in this strategy receive training. For more information, visit Pyramid Educational Consultants, Inc., at https://pecsusa.com/.

Ilene Schwartz discusses the importance of teaching children effective communication skills.

Ilene Schwartz, PhD

Professor Emeritus, Special Education

Director, Haring Center for Research and Training in Inclusive Education

University of Washington

(time: 1:18)

Transcript: Ilene Schwartz, PhD

One of the most important skills that we teach any child, but especially children with autism, is to communicate, because communication is power, and communication gives you the ability to control your environment. When you teach a child to communicate, all of a sudden they can ask for anything they want, and their world opens up. For students in our program who are non-verbal, we very often use the Picture Exchange Communication System. One of the reasons our children have had so much success with it is that, from the very beginning of the system, you teach children how to request their very favorite things.

The kind of items you want to teach children to ask for at first are the items that children will climb over the table to get, and all of a sudden they’re learning that if they give you this card then you give them their very favorite item. And what that does is it really teaches children the function of communication, that you give me this and I give you that. And when you see children learn that function of communication, often you see their communicative skills just take off.

TIPS: Engaging and Supporting Young Children

Young children with autism are often more difficult to engage and need more support than do typically developing children. Teachers can embed the following concepts into the natural environment and daily routines to help these children be socially and academically successful.

- Engage the child in play to encourage social interactions and communication. One way to do this is to use the child’s preferred objects and play routines.

- Incorporate the child’s interests into activities to help engage the child or transition the child to a non-preferred activity.

- Use visual cues to offer choices (e.g., a cookie or cracker during snack time) so that the child can express preferences.

- Provide visual cues when it is time to transition to another activity to help the child understand what is coming next (e.g., a picture of the block area).

- Create clearly defined and predictable spaces in the classroom for given activities to provide consistency and to cue the student to what activity is about to occur (e.g., art corner, reading center).

- Create predictable routines that are displayed visually to help the child transition throughout the day.