How do you develop an effective behavior management plan?

Page 8: Crisis Plan

Once teachers have developed a statement of purpose, rules, procedures, and consequences, they should consider how they will address severe behavioral situations, such as when a student is out of control, potentially self-injurious, or possibly harmful to others. Although such behaviors are relatively infrequent, their physical and emotional by-products can be intense and exhausting. To more effectively address these types of situations when they do occur, teachers should develop a crisis plan—a preplanned and well-thought-out set of strategies for obtaining immediate assistance in the event of severe behavioral situations. When teachers have such a plan in place, they are more likely to:

Once teachers have developed a statement of purpose, rules, procedures, and consequences, they should consider how they will address severe behavioral situations, such as when a student is out of control, potentially self-injurious, or possibly harmful to others. Although such behaviors are relatively infrequent, their physical and emotional by-products can be intense and exhausting. To more effectively address these types of situations when they do occur, teachers should develop a crisis plan—a preplanned and well-thought-out set of strategies for obtaining immediate assistance in the event of severe behavioral situations. When teachers have such a plan in place, they are more likely to:

- Respond effectively to the situation

- Gain control of the situation

- Take charge of their emotions and avoid escalating the situation

- Experience less anxiety, fear, or frustration related to handling the crisis

Mr. Medina’s Behavior Crisis Plan

- Call the office. If not possible, send a student to the office with a crisis behavior card.

x

crisis behavior card

glossary

- Send the rest of the class to Mrs. Simpson’s room.

- If possible, help the student in crisis to reestablish self-control.

- Bring the rest of the students back to class once the crisis has been addressed.

- Notify parents of incident.*

* Depending on school policy, this step might be completed by a school administrator.

To be effective, a crisis plan should address the four questions listed below. As you examine Mr. Medina’s behavior crisis plan to the right, take particular note of how it addresses each of these questions.

- Who will seek assistance?

- Who will be notified?

- What do you want the rest of the students to do during the crisis?

- What will you do once the crisis is over?

Note: Be sure to check whether your school has established procedures for addressing such a crisis (e.g., who to notify in a crisis situation, where the other students should go, teacher guidelines for physical intervention).

It is important that teachers understand that a student in a crisis situation may have little to no control over her behavior, as well as that the precursors to a crisis do not always occur in the classroom. Still, it is critical that teachers recognize what a student is experiencing during a crisis, what specific steps can deescalate crisis situations, how to access immediate assistance from colleagues, and how to manage crisis events when they occur. For more information on how teachers can prevent a student’s behavior from escalating and can avoid a behavior crisis altogether, view the following IRIS Modules:

- Addressing Challenging Behaviors (Part 1, Secondary): Understanding the Acting-Out Cycle

- Addressing Challenging Behaviors (Part 2, Secondary): Behavioral Strategies

Listen as Michael Rosenberg, a researcher and expert in behavioral interventions, explains why teachers should develop a behavior crisis plan to address out-of-control behavior. Next, KaMalcris Cottrell further discusses the need to do so.

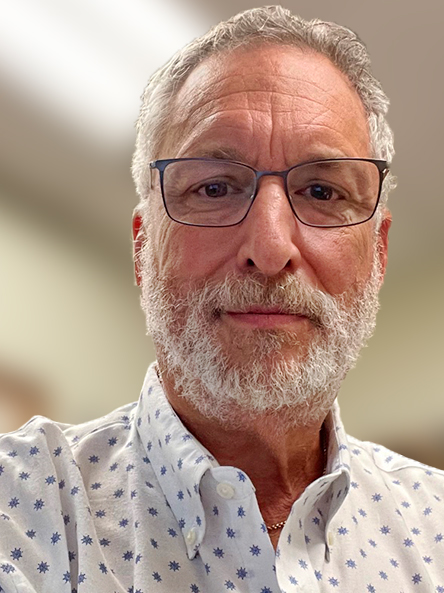

Michael Rosenberg, PhD

Professor, Special Education, SUNY New Paltz

Professor Emeritus, Johns Hopkins University

(time: 1:06)

Transcript: Michael Rosenberg, PhD

For the most part, students, when they do engage in disruptive behaviors, tend to engage in minor attention-seeking types of actions. When a student may engage in a pretty severe acting-out behavior, one that threatens themselves or other students, it is very useful to have a behavior crisis plan. In many cases, these behavior crisis plans involve having a preselected series of actions of what you’re going to do if a student engages in a crisis type of action, such as throwing a dangerous object, jumping on desks, things like that. One might be a signal that one would have to go and get support from other people in the building. Another action might be a room-clear, where all of the other students know to clear the room to maintain safety for everyone involved.

Transcript: KaMalcris Cottrell

It is imperative to have a crisis plan in place, because it’s going to happen. So if we have it in place, everyone’s going to be on the same page during the crisis, because there’s usually not much time to communicate in the crisis. The most important thing is the safety of the student, the safety of the staff that will be interacting with the student. It’s important to know who’s going to be in the lead when dealing with this crisis. Many times, if you have multiple adults talking to one student who’s already escalated, it doesn’t go well. They don’t receive it well. They’re at a point where even one adult speaking to them is not always received well. So I think it’s important to know who will lead, who will be the speaker. I think it’s also important to have a place where the student can go to de-escalate, a safe space within the school that the person can be walked to. Usually if a student is in a heightened state, use short, direct statements—”Please follow me. Can we go down this hall?”—and then give time to process. I mean, of course, it all always depends on the level of the escalation, but usually they’re willing to get out of the situation to go somewhere else, and that’s what you’re affording them to do.

So as long as you have that safe space for the de-escalation is great. The teacher should have a chance to say what happened, but not in front of that student and hopefully not in front of her classroom either. That debriefing should happen away from the student. So within that response team, if there’s someone who can stay with her class, if it’s that important that that message needs to be delivered right away, that would be great. If it can wait until the end of the day, also wonderful. But that information should not be given in front of the classroom or in front of the student who was in the crisis mode. Within that classroom for the de-escalation, it’s important to allow the child to go through the entire cycle. You can’t explain to them when they’re at the top of their crisis mode. It’s important to let them come back down so that emotional and that physical intensity has released. And that may be them crying. It could be them being super lethargic now, even to the point of falling asleep. But I think it’s important to let that process take place and then go back to revisit before we do our restorative practices so you can touch on what happened, why it happened, what to do next time, and how do we do that, and who do we need to apologize to? So within the construct of the cycle of escalation/de-escalation, we let that happen and then we can speak with the student. And, again, it should be a one-on-one or small-group setting just so you’re not overwhelming the student.

Activity

![]() As you have already learned, a well-thought-out behavior crisis plan is crucial to the safety of your students.

As you have already learned, a well-thought-out behavior crisis plan is crucial to the safety of your students.

Click here to develop your own crisis plan. Keep in mind that your school may have guidelines in place for developing behavior crisis plans. If so, make sure your crisis plan aligns accordingly.

Supporting Students Who Experience Trauma

Trauma, which might impact a student’s self-regulation, arousal, social skills, learning, and focus, can lead to everything from academic difficulties to behavioral crisis situations. Teachers should understand how trauma negatively impacts learning and behavior and should recognize the signs of trauma in their students. Below are some practices teachers can use to support students who are experiencing trauma.

- Collaborate with students and families — Collaborating with the family can help the teacher understand what the student is going through; create a safe, supportive environment; and prevent crisis situations from developing.

- Build relationships — A secure, positive relationship with a teacher can safeguard a student from the effects of trauma.

- Have a consistent routine — Such a routine creates a sense of safety and predictability. If changes in the routine do become necessary, take care to prepare students for them in advance. When students know what to expect, they are more likely to relax and focus on instruction.

- Help students learn to identify and regulate their emotions — Teach students strategies like deep breathing, stretching, mindfulness, and movement to help better manage their emotions and behaviors.

- Promote empowerment of students — Whenever possible, offer students choices to help them feel in control of their situation. Highlight their skills and talents to combat self-doubt and negative feelings about themselves.

- Interrupt negative thinking — Help students break a negative cycle of thinking with a distracting activity (e.g., assisting a peer, running an errand, reading a book).

- Don’t take negative behavior personally — Remain calm and objective and recognize that inappropriate behavior may stem from trauma. Let students know that you are always there for them.

Unfortunately, childhood trauma is quite prevalent. Data from 2016 indicate that 45% of children have had at least one experience that can lead to trauma and have harmful aftereffects on multiple domains of a child’s life. For more information on identifying and addressing childhood trauma, view the following resources.