How can school personnel intensify and individualize instruction?

Page 8: Implementation Considerations

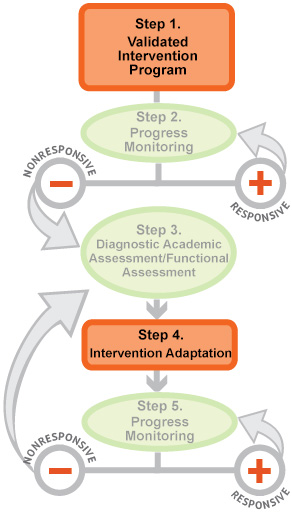

Now that we have reviewed the four types of instructional adaptations, we are ready to examine when and where they can be implemented in the DBI process to intensify and individualize instructional interventions. Recall, there are two steps in the process when teachers are expected to adapt the intervention.

- Step 1: Validated Intervention Program—Teachers should intensify the secondary intervention by making quantitative changes (e.g., increase amount of instructional time, decrease group size).

- Step 2: Progress Monitoring

- Step 3: Diagnostic Assessment

- Step 4: Intervention Adaptation—Following progress monitoring and a diagnostic assessment, teachers can adapt the intervention by making quantitative and/or qualitative changes (e.g., the way in which content is delivered).

- Step 5: Progress Monitoring

This graphic illustrates both the steps of data-based individualization, as well as they ways in which those steps interact. Step 1, “Validated Intervention Program,” is represented by an orange rectangle. This box connects via a vertical grey line to Step 2, “Progress Monitoring,” which is illustrated as a green oval. Both steps, in turn, are connected to a horizontal line with labeled circles at each of its ends. The circle on the left, “Nonresponsive,” has a red minus sign at its center, while the circle on the right, “Responsive,” has a red plus sign. A grey arrow connected to the “Nonresponsive” circle points toward Step 3 of the DBI process, “Diagnostic Academic Assessment/Functional Assessment,” which is represented as a green oval, similar to Step 2. The “Responsive” circle also has a grey arrow, this one pointing back up toward Step 2, “Progress Monitoring.”

Step 3 is connected via a vertical grey arrow to Step 4, “Intervention Adaptation,” represented as an orange rectangle. Another grey arrow connects Step 4 to Step 5, “Progress Monitoring,” another green oval. As above, these latter steps are connected to a horizontal line with labeled circles at each of its ends. The circle on the left, “Nonresponsive,” has a red minus sign at its center, while the circle on the right, “Responsive,” has a red plus sign. A large grey arrow connected to the “Nonresponsive” circle points back to Step 3, “Diagnostic Academic Assessment/Functional Assessment,” while the “Responsive” circle directs instructors back to Step 5, “Progress Monitoring.”

This module page focuses on Steps 1 and 4, so those orange boxes are highlighted whereas the rest of the graphic is slightly faded out.

It is recommended that teachers make quantitative changes in Step 1 because they are easy to implement and, sometimes, simple adaptations such as increased intervention time or a smaller group size is all a student needs to succeed. However, if the data clearly indicate that the student needs even more intensive instruction in Step 1, the teacher can begin intensifying the validated intervention by making qualitative adaptations. If the data indicate that the student is not responding adequately to the adaptation(s) made during Step 1, the team can decide whether to make additional adaptations to the intervention. During Step 4, these adaptations can be quantitative and/or qualitative.

Who Delivers Intensive Intervention?

Depending on a school’s available resources, a variety of qualified individuals—for example, an intervention provider, a special education teacher, or others—can provide the intensive intervention. Regardless of who provides the intervention, a team of school professionals should be involved in making instructional decisions for individual students based on their data.

Regardless of whether a teacher is implementing Step 1 or Step 4, there are several factors critical for successfully implementing the DBI process. First, the teacher should try to align the intervention with the core curriculum. Next, the teacher should implement the adaptations systematically and with fidelity.

Align Intervention with the Core Curriculum

Russell Gersten, the Executive Director of the Instructional Research Group, explains that intensive intervention should build on foundational skills and the core curriculum as opposed to introducing unrelated curriculum (time: 2:11).

Transcript: Russell Gersten

Narrator: What is the relationship between foundational skills and the core curriculum within intensive or Tier 3 interventions?

Russell Gersten: This one we began discussing when I was actually with Lynn Fuchs on a panel talking about access to the general curriculum—this was probably about a dozen years ago—and the importance of foundational skills was something we in particular noted, and it’s critical for intensive interventions. What I would not like to see is intensive interventions that are standalone, so the school says for Tier 3 we put our students in “Read for X” or “Reading Made Easy” or something like that, and it’s a program that’s totally isolated from what’s going on in the core.

What I’d like to see is something that systematically builds skills in these foundational areas, which would include, certainly for reading, language comprehension, listening comprehension, vocabulary, as well as how to read, fluent decoding. I’d like to see that, and then what is ideal, what is critical for Tier 2 but ideal for intensive interventions, is that there are linkages. For example, with students in a middle school you’d be really working intensively on concepts, ideas related to fractions, adding fractions, multiplying fractions, and there was some clear linkage to what’s happening in pre-Algebra for these kids.

Implement Adaptations Systematically

When making instructional adaptations, it is critical that teachers do so systematically. Teachers should implement a few changes at a time and collect data so that they can isolate and identify which changes (if any) result in improved student performance. Listen as Devin Kearns, a research scientist at the Center for Behavioral Education and Research, discusses why it is important to make systematic changes when adapting an intervention (time: 1:36).

Transcript: Devin Kearns

Narrator: Why is it important to make changes in a systematic way when adapting interventions for students with intensive needs?

Devin Kearns: One really important aspect of data based individualization is that you make decisions and make changes in a systematic way. So, if you begin an intervention that you thought through with a team and you begin to feel like it’s not exactly what you wanted, it’s not getting the effect achieved, you should probably stick with it for about four weeks to see whether or not it is improving a student’s academic performance at the rate you anticipated. If it isn’t, you should change it. But it’s important not to move things around too quickly, because if you do that then you aren’t certain whether or not the changes you are getting are due to which part of it you have changed. You want to make these changes in a systematic way, and changing things in a systematic way means you need to make a decision and stick with it for at least four weeks to see whether or not the student is at the aim line, above it, or below it. And if they are below it then you should make the change that you have. Now of course, if the student is sort of dive-bombing in their performance where they were doing ok and we are seeing this huge problem as a result of the intervention then you should stop it. But it’s pretty rare that that would occur, and so it’s important to sort of stick with your decision and see how it plays out.

Next, listen as Sarah Arden discusses considerations related to determining how many adaptations to make at once (time: 1:13).

Sarah Arden, PhD

Technical Assistance Team,

National Center on Intensive Intervention

Transcript: Sarah Arden, PhD

That’s a really delicate balance to strike. You want to be able to, when you make a change, understand what change is it that worked. So you don’t want to make so many slow changes at once that you’re just adding one kid, or removing one kid and adding five minutes, or adding ten minutes, and now you’re slowly making these changes. I think that with the right kind of diagnostic assessment, you can start to understand is this student that needs some of these, what I call first-line quantitative assessments, like more time or a smaller group? And usually you can you can tell pretty quickly is that really the issue here? Or is the issue that the intervention needed to be changed inherently? Did we need to change the kind of instruction or the kind of feedback or the type of teaching that’s happening? I think those kind of changes can happen at the same time. It’s possible to change the amount of students and increase the kind of feedback or the amount of feedback that happens together. What you don’t want to do is change the intervention, change the interventionist, change the amount of time, change the amount of kids, and then maybe change the skill, because then it’s really hard to tell what change helped the student or maybe didn’t help the student.

Implement Adaptations with Fidelity

In addition to implementing interventions systematically, it is also critical that teachers implement them with fidelity, that is implement them in the way the instructional decision-making team intended. For example, the team decides that a student would benefit from explicit instruction. To determine to what extent the teacher is delivering the adaptation with fidelity, an experienced or trained individual should be responsible for monitoring the teacher’s instruction. By doing so, the team can determine whether or not the adaptation was delivered as planned. If the intervention is delivered with fidelity and the student shows improvement, the team can conclude that the adaptation(s) was effective for this student. The National Center on Intensive Intervention has developed resources that teachers can use to monitor their fidelity of implementation.

Student-Level Data-Based Individualization Implementation Checklists

Data-Based Individualization Implementation Log: Daily and Weekly Intervention Review

For Your Information

In many cases, students who struggle academically also display behavioral problems. The advantage of the DBI process is that it can be used to address both academic and behavioral problems. Although this module focuses on the provision of intensive intervention to students struggling academically, the DBI process can also be used to provide intensive behavioral intervention for students with severe and persistent behavioral difficulties.