How can the Rosa Parks teachers effectively implement the RTI components in each tier?

Page 4: Universal Screening

As he begins Tier 1 instruction, Mr. Brewster will administer the universal screening measure. He will then use the data to:

- Verify whether students should remain in the existing small groups or determine whether the groups need to be restructured

- Identify students who are potentially struggling with reading and who need to be monitored frequently to determine if intervention would be beneficial

Administering the Universal Screening Assessment

Teachers should schedule the administration of the universal screening assessment to fit their schedules and their classrooms’ needs. The S-Team and the principal at Rosa Parks have decided that all universal screenings should be completed by mid-September (i.e., two weeks after school begins), so Mr. Brewster chooses to conduct the screenings during the last 10 minutes of reading class while his students are engaged in independent practice. By screening four to five students a day, he anticipates that he can easily assess all 24 by the end of the second week, if not earlier.

Teachers should schedule the administration of the universal screening assessment to fit their schedules and their classrooms’ needs. The S-Team and the principal at Rosa Parks have decided that all universal screenings should be completed by mid-September (i.e., two weeks after school begins), so Mr. Brewster chooses to conduct the screenings during the last 10 minutes of reading class while his students are engaged in independent practice. By screening four to five students a day, he anticipates that he can easily assess all 24 by the end of the second week, if not earlier.

Although the first-grade teachers at Rosa Parks are using a Dolch sight word list for the universal screening, the second-grade teachers are using a one-minute reading (curriculum-based measurement) probe. They have chosen to use a different measure for two primary reasons. First, research indicates that while the Dolch sight word list may be sufficient and even superior to other assessments for identifying potentially struggling first-grade students, the data also indicate that an assessment using curriculum-based measurement (CBM) is better at identifying struggling second-grade students. In addition, the second-grade teachers had planned to use CBM Passage Reading Fluency (PRF) probes for their weekly progress monitoring data collection and thought it would be easier and more convenient to use the same materials for both assessments (i.e., universal screening and progress monitoring).

Although the first-grade teachers at Rosa Parks are using a Dolch sight word list for the universal screening, the second-grade teachers are using a one-minute reading (curriculum-based measurement) probe. They have chosen to use a different measure for two primary reasons. First, research indicates that while the Dolch sight word list may be sufficient and even superior to other assessments for identifying potentially struggling first-grade students, the data also indicate that an assessment using curriculum-based measurement (CBM) is better at identifying struggling second-grade students. In addition, the second-grade teachers had planned to use CBM Passage Reading Fluency (PRF) probes for their weekly progress monitoring data collection and thought it would be easier and more convenient to use the same materials for both assessments (i.e., universal screening and progress monitoring).

curriculum-based measurement (CBM)

A type of progress monitoring conducted on a regular basis to assess student performance throughout an entire year’s curriculum; teachers can use CBM to evaluate not only student progress but also the effectiveness of their instructional methods.

passage reading fluency probe

A form of curriculum-based measurement (CBM) in which the student reads a passage for one minute; the student’s score is the number of words read correctly per minute; this probe is appropriate for students in second through sixth grade and should be administered to each student individually.

For a demonstration of how to administer PRF as the universal screening assessment, click on the portrait of Louisa to the left.

How To Administer PRF

A demonstration of how to administer PRF as the universal screening assessment.

(time: 3:01)

Ms. Begay: Louisa, I want you to read this story to me. You’ll have one minute to read. When I say “begin,” start reading aloud at the top of the page. Do your best reading. If you have trouble with a word, I’ll tell it to you. Do you have any questions?

Narrator: Before we watch Ms. Begay administer and score the Passage Reading Fluency test, let’s go over the scoring rules:

- Words read correctly are scored as correct.

- Words that are mispronounced, omitted, substituted, or reversed are counted as errors.

- Repetitions and insertions are ignored.

- If the student self-corrects within three seconds, the word is counted correct.

- If the student hesitates for more than three seconds, the word is provided by the teacher and it is counted as an error.

Ms. Begay: Begin.

Louisa: [Reads passage.]

Ms. Begay: Stop.

Narrator: Here is Louisa’s scored passage.

She made a total of five errors. Two were words she struggled with and was provided. Two were mispronunciations, and one was omitted. Louisa also repeated one phrase, but this is ignored according to the scoring rules for Passage Reading Fluency. Louisa also replaced the word “was” with “were” but changed it back within three seconds, so it was counted correct.

To score this passage, Ms. Begay figures out the number of words Louisa read in one minute. She uses the numbers at the end of each line in the passage to help. Louisa finished with the word “am.” Ms. Begay looks at the line before the last word. There are 56 words. She then counts the number of words in the next line, 57, 58, 59, 60, 61. So Louisa read a total of 61 words. She made five mistakes, so five is subtracted from the total number of 61, which is a score of 56 correct words read in one minute.

Now that Mr. Brewster has completed the universal screening with all of his students, he is ready to restructure his small groups. Because his original grouping was based on last year’s assessment data, Mr. Brewster only has to make a few changes to his original group assignments. In addition, he will begin collecting progress monitoring data for those students who scored in the bottom 25 percent of the class on the screening—the criteria determined by Rosa Parks school personnel to identify students as potential struggling readers.

Grouping

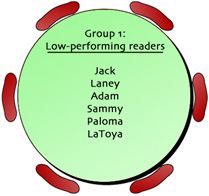

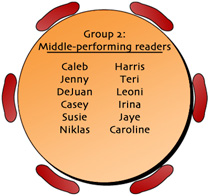

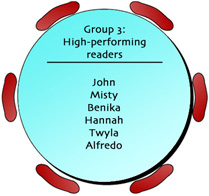

Once Mr. Brewster has collected the universal screening data for each of his students, he rank-orders the scores so that he can determine how best to group his students. Mr. Brewster can go about this in a variety of ways, including same-ability grouping and mixed-ability grouping. Mr. Brewster decides that by grouping the students according to ability level (same-ability grouping), he can more effectively differentiate instruction and, as a result, better address each student’s instructional needs. After carefully reviewing the scores, he divides the students into three groups based on performance level: low, middle, and high.

Once Mr. Brewster has collected the universal screening data for each of his students, he rank-orders the scores so that he can determine how best to group his students. Mr. Brewster can go about this in a variety of ways, including same-ability grouping and mixed-ability grouping. Mr. Brewster decides that by grouping the students according to ability level (same-ability grouping), he can more effectively differentiate instruction and, as a result, better address each student’s instructional needs. After carefully reviewing the scores, he divides the students into three groups based on performance level: low, middle, and high.

Below are the universal screening results for the students in Mr. Brewster’s class. The color-coding differentiates the three groups and will be used to represent the three performance levels for the remainder of this page and on the next.

* Students who scored in the bottom 25 percent of the class on the universal screening measure must have their progress monitored. |

|

|

As depicted in the table above, Mr. Brewster’s middle-performing group is the largest, with 12 students, whereas each of the other two groups contain six students. It is usually a good idea to limit the number of students in the low-performing group to five or six. The three groups are represented by the tables above.

Maintaining flexible grouping techniques

Instruction for a group of 12 students may look a lot like whole-group instruction. If this is the case and the teacher cannot effectively differentiate instruction to meet the needs of all the students within the group, then the teacher may want to consider one of the following options:

- Assign more students to the above–average-ability group.

- Split the average-ability group into two.

When employing small-group instruction, it is important to remember that the groups should be flexible. Throughout the year, teachers should reorganize small groups as students’ reading abilities improve or as students begin to struggle with certain skills.

Activity

Review your initial groupings for Mr. Brewster’s class on Perspectives and Resources Page 3. Compare how you grouped Mr. Brewster’s students to how Mr. Brewster grouped them following the universal screening. Discuss the similarities and differences of your initial student grouping and Mr. Brewster’s.

Keep in Mind

During the school year, Mr. Brewster can continually reorganize these small groups as students’ reading skills improve or as students begin to struggle. For example, Caroline’s scores on the universal screening initially led Mr. Brewster to place her in the middle-performing group; however, after several weeks of observing Caroline during small-group instruction, it becomes apparent that she would benefit more from the instruction provided in the high-performing group.

Identifying Potential Struggling Students

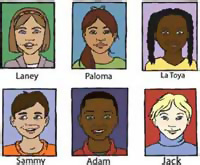

Those students who scored in the bottom 25 percent of the class on the universal screening assessment (the criteria determined by Rosa Parks school personnel to identify students as potential struggling readers) are noted by asterisks in the table above. They are Jack, Laney, Paloma, Sammy, Adam, and LaToya. Mr. Brewster will monitor all of these students, except for Jack (see box below for more information), for the next eight weeks.

Jack’s Story

As Mr. Brewster learns from viewing the students’ files from previous years, Jack was identified as having a learning disability in first grade and his individualized education program (IEP) was developed at this time. He has been receiving special education (Tier 3) services ever since. Because he has an existing IEP, Jack has already begun Tier 3 intervention this year with the special education teacher, Ms. Jacobs. She will collect progress monitoring data on him and will discuss the results with Mr. Brewster on a regular basis. For this reason, Mr. Brewster will not collect progress monitoring data on Jack during Tier 1 instruction.

As Mr. Brewster learns from viewing the students’ files from previous years, Jack was identified as having a learning disability in first grade and his individualized education program (IEP) was developed at this time. He has been receiving special education (Tier 3) services ever since. Because he has an existing IEP, Jack has already begun Tier 3 intervention this year with the special education teacher, Ms. Jacobs. She will collect progress monitoring data on him and will discuss the results with Mr. Brewster on a regular basis. For this reason, Mr. Brewster will not collect progress monitoring data on Jack during Tier 1 instruction.

individualized education program (IEP)

A written plan used to delineate an individual student’s current level of development and his or her learning goals, as well as to specify any accommodations, modifications, and related services that a student might need to attend school and maximize his or her learning.