Why do so many adolescents struggle with content-area reading?

Page 1: Middle School Literacy

Content-area teachers are often frustrated by the poor reading abilities of many of their students. Learning the material in subjects such as science, social studies, and English/language arts largely depends on grade-appropriate reading skills. Because of this, it is important for content-area teachers to understand where reading breakdowns occur and how they can effectively and efficiently teach the skills necessary for students to read and understand complex, content-area text (e.g., textbook chapters, articles, historical documents, website content, novels). These are prerequisites to accomplishing more advanced literacy activities.

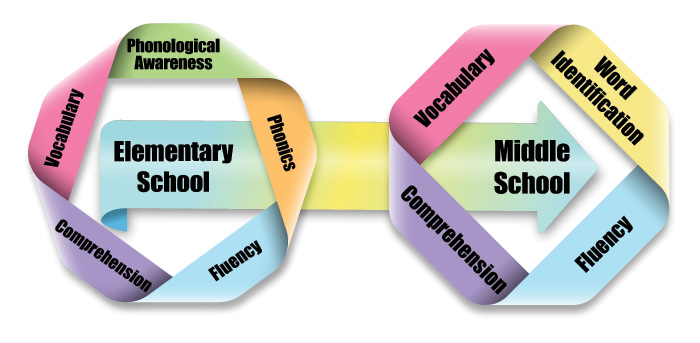

Many teachers—especially those at the elementary level—are familiar with the five essential reading skills: phonological awareness, phonics, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Although these building blocks of skilled reading apply to all ages or grade levels, most students will have mastered phonological awareness and the basics of phonics by the end of third grade. Once students reach middle school, however, the reading skills required for success shift slightly: Word identification replaces both phonological awareness and phonics.

Middle school students are particularly heterogeneous. That is, they tend to exhibit different patterns of reading strengths and weaknesses. Even so, about half of those who struggle with reading will benefit from instructional support in word identification and nearly all need help with grade-level comprehension.

Listen as Don Deshler discusses some of the reasons that a class of middle school students can display a wide range of reading abilities. (time: 2:56).

Don Deshler, PhD

Professor, Special Education

Director, Center for Research on Learning

The University of Kansas

Transcript: Don Deshler, PhD

A common assumption is that by the time students reach middle school, they should have well in tow some basic reading skills that would enable them to respond to the demands of the curriculum. Unfortunately, reality tells us that’s not the case, but rather students’ abilities and skill levels are distributed quite broadly. Among the possible reasons are first of all some students who reach middle school simply did not have the kind of instruction that they needed during the elementary grades. It may have been that they were moving quite a bit as a family or perhaps the nature of the instruction they received was not solid and then as they moved into the middle schools they weren’t prepared.

Secondly, we know that there are some students who perform quite well in elementary school. However, when they move into middle school or upper elementary, the demands of the curriculum tend to change. That is, the things that students are expected to read, the complexity of the text, the abstractness, and so forth is often dramatically different than what they have encountered and experienced in the elementary years. And so, whereas before they were evidencing no difficulties, now with this new instructional dynamic some difficulties may emerge.

Another explanation is that some students seem to need more basic skill instruction beyond grade three than most students. But curriculum-wise, in-depth, intense reading instruction is not offered as we move into upper elementary. And so students who hadn’t quite become solid in the core-reading skills in the early elementary grades, now they’re in upper elementary moving into middle school. They’re struggling. These struggles start to manifest themselves in the students’ feelings about themselves. And now they start to push back and avoid reading. And the thing that they need practice on is more reading, but now they start avoiding it.

On the other hand, some of their peers who have acquired these basic skills and are very fluent at reading are now very much into reading, and so they read because it’s reinforcing. And so this gap between those who are struggling and those who are doing well starts to broaden

Research Shows

- A study of middle school struggling readers reveals that:

- 47% have difficulty with word identification.

- Of the 47%, nearly all of them also struggle with fluency and/or comprehension.

- 84% struggle with comprehension either in isolation or in combination with other reading skills.

(Cirino et al., 2013)

- The gap between those with lower and higher reading ability seems to widen through the middle grades. Researchers found that:

- 37% of third grade classes have students spanning five or more grade levels in comprehension and fluency ability.

- 65–67% of the fourth- and fifth-grade classes demonstrate the 5+ grade-level range in students’ abilities.

(Firmender et al., 2012)

Problems with any of the reading skills—word identification, fluency, comprehension, or vocabulary—can contribute to reading difficulties in middle school. When students cannot quickly and accurately recognize long and difficult words (word identification), it affects their reading rate (fluency). Not knowing the meanings of words as they are used in a given text (vocabulary) and a lack of fluency contribute to difficulties in reading comprehension. In other words, to be skilled readers, students must integrate all their word identification, fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension skills.

Content-area teachers are often surprised when their students lack one of the most basic reading skills: word identification. Middle school students commonly struggle to pronounce the longer, more difficult words prevalent in content-area textbooks. These words represent a marked shift from the short, decodable words that make up the bulk of early elementary reading. Whereas a second grader who could not read the word cat would be identified as struggling, a student in the eighth grade would be considered to have a word identification problem if he could not read the word catastrophic.

Did You Know?

College and career readiness standards, such as the Common Core State Standards (CCSS), place increased importance on reading grade-level texts from a variety of genres, with greater focus on higher-order skills such as analyzing the texts and the ideas contained therein. Some argue that these expectations are too challenging because students have not been exposed to or provided sufficient opportunities to learn from complex texts.

Some of these students struggle because they have not had instruction about how to break down the word into pronounceable chunks (e.g., cat-a-stroph-ic). Others may know how to break the word apart but are self-conscious about doing it in front of their peers or are overwhelmed by the number of words they would have to identify. Regardless of the reason, these students are likely to skip over such words entirely, unless the teacher or another more capable reader identifies the word for them. Mastery of any skill—athletic, academic, artistic, technical—requires effective instruction and lots of practice. Reading is no exception. Students need instruction and practice in the essential reading skills to become more proficient. Further complicating matters is that many content-area teachers try to circumvent students’ reading difficulties by reading the texts to them or summarizing the information, which has the effect of eliminating the practice needed to become better readers.

In the interviews below, Deborah Reed discusses challenges and potential solutions to teaching adolescents with a wide range of literacy skills while Don Deshler offers insight into the skills that these students need to be college and career ready.

Deborah K. Reed, PhD

College of Education, University of Iowa

Director, Iowa Reading Research Center

(time: 1:22)

Don Deshler, PhD

Professor, Special Education

Director, Center for Research on Learning

The University of Kansas

(time: 2:20)

Transcript: Deborah Reed, PhD

One of the things that makes it difficult for teachers to integrate literacy strategies into the content-area classrooms is if they feel as though they have to stop everything that they are doing and only address the students who are really struggling with reading and with the literate activities in the class. And you have such a broad range of student abilities in middle and high school classes that there are also those students who are at the higher end of the spectrum who are really excelling. And so things get very inappropriate for both the lower-achieving students and the higher-achieving students if we have to stop and do very distinct activities or provide very distinct kinds of instructional supports for both ends of the spectrum that don’t make any sense across that full range of student abilities. And so the things that we’ve incorporated in this module—like Possible Sentences and the Anticipation-Reaction Guides—are nice in that they can be accommodated to serve both the students who are struggling as well as students who are more advanced. They have built-in mechanisms for differentiating the activities for students at different ability levels.

Transcript: Don Deshler, PhD

As students move into the middle school years and early high school, it becomes very clear that in order to be successful they need to have in their toolbox a broad array of literacy skills. When we look at it just from the core reading components, they need a solid grasp of word identification so that they can very quickly, as they encounter new words, have strategies for decoding those words or reading within context to figure out what the words are.

Secondly, they need to be fluent readers. They need to have a rich vocabulary and/or an ability to acquire vocabulary as they move along because they’ll certainly acquire or encounter new vocabulary, and so they need to have some strategies that enable them to explore those new words. And then finally they need to, of course, have an array of comprehension strategies. The reason I say an array is because the text demands change. For example, a novel and the way it is structured and laid out and organized is quite different than the way a science book is organized and structured and the language patterns and so forth. And so the kinds of strategies that a student needs to successfully navigate narrative text—as opposed to expository text—are different.

So there’s a broad array of skills and dispositions that are needed in order for students to successfully navigate the materials that are immediately before them. But the big picture is: Are we putting kids in a position to be ready for college, ready for careers, and in some instances, of course, responding to state standards?