Why do so many adolescents struggle with content-area reading?

Page 2: Text Complexity

Adding to middle school students’ difficulty with word identification is the increased complexity of content-area textbooks. Reading experts have defined text complexity in different ways, and there are many factors that influence it. For example, college and career readiness standards (i.e., Common Core State Standards) view three interrelated components as integral to text complexity: quantitative dimensions, qualitative dimensions, and reader and task considerations.

Quantitative Dimensions

Many teachers are familiar with quantitative dimensions of text complexity. These factors include readability aspects such as:

- Word length (e.g., simple versus multisyllabic words)

- Frequency of unfamiliar or new vocabulary terms

- Sentence length and complexity

- Text cohesion

text cohesion

The explicitness with which meanings and relationships between and among words and concepts are conveyed.

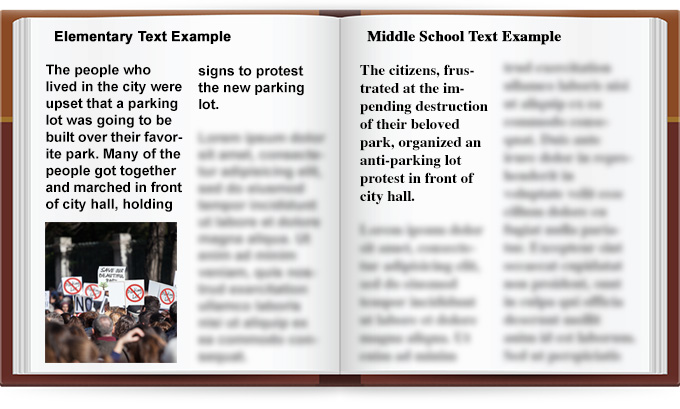

Consider the following two text excerpts, one from an elementary level text (left) and another from a middle school text (right).

This graphic shows an open textbook, with the left leaf representing an example of typical elementary school content-area text, and the right leaf representing an example of how that same content might appear in a middle school text. The left side is titled “Elementary Text Example” and continues with a two-column text format that reads as follows: “The people who lived in the city were upset that a parking lot was going to be built over their favorite park. Many of the people got together and marched in front of city hall, holding signs to protest the new parking lot.” At the bottom of the first column is a photograph to illustrate the passage’s content. The picture shows a protest in progress with people holding signs announcing their opposition to the proposed development. The right side of the textbook is titled “Middle School Text Example.” The text reads “The citizens, frustrated at the impending destruction of their beloved park, organized an anti-parking lot protest in front of city hall.” There is no accompanying photograph or illustration.

Both examples convey the same information. However, note that the elementary level text does so using 43 short, easy-to-understand words in two sentences and is accompanied by a photo to illustrate the content. The text in the middle school example is condensed, using only 21 words and one sentence. This sentence—which contains more multisyllabic and potentially unfamiliar words—would be more difficult for some students to read and understand. Further, though the fact that the park is to be replaced by a parking lot is directly stated in the elementary example, this information is only implied in the middle school text. This would place extra pressure on students to make connections across information presented in different sources or in different places of a given text. The more inferences the reader needs to make, the more difficult the text can be to comprehend. Given the text complexity issues that this one sentence presents, it is understandable that an entire page—or chapter or unit—of text could overwhelm students.

Qualitative Dimensions

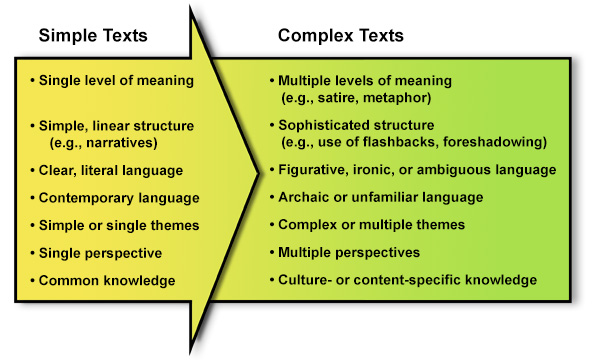

Various qualitative aspects can affect a text’s complexity and, consequently, a reader’s comprehension. The graphic below highlights some of the differences between simple and complex texts.

This graphic shows the characteristics of a simple text and how those develop into and differ from the characteristics of a complex text. On the left side of the graphic titled “Simple Texts” is a large yellow arrow pointing to the right. Characteristics of simple texts are bulleted in the arrow as follows: simple linear structure (e.g., narratives); clear, literal language; contemporary language; simple or single themes; single perspective; common knowledge. The arrow leads to a large green rectangle titled “Complex Texts.” Characteristics of complex texts are bulleted in the rectangle as follows: multiple levels of meaning (e.g., satire, metaphor); sophisticated structure (e.g., use of flashbacks, foreshadowing); figurative, ironic, or ambiguous language; archaic or unfamiliar language; complex or multiple themes; multiple perspectives; culture- or content-specific knowledge.

academic language

The language used in academic settings to communicate information orally and in writing about discipline-specific content.

In contrast to conversational language, content-area texts use academic language, which contains sophisticated, specialized, subject-specific terminology. Academic language is often used to convey abstract concepts that are harder for students to grasp or that require students to engage in more in-depth informational processing than they are used to in casual or pleasure reading. Finally, content-area texts often have high knowledge demands—assumptions that the readers have a prerequisite level of background or content knowledge. All of these facets contribute to the difficulties that students have reading and comprehending content-area texts. In the interviews below, Paola Uccelli, discusses five key ideas related to academic language and learning and the implications for classroom teachers. In the interviews below, Paola Uccelli, discusses five key ideas related to academic language and learning and the implications for classroom teachers.

Paola Uccelli, EdD

Associate Professor of Education

Harvard Graduate School of Education

How does language affect learning?

(time: 2:27)

What are the implications for educators?

(time: 2:53)

Transcript: Paola Uccelli, EdD

How does language affect learning?

When we think about academic language we are thinking about the language of school, which refers broadly to the language we use at school for learning purposes. And this language is most typically found in written text, such as textbooks, and scientific or historical, or literary essays. However academic language is not exclusively written. For instance students and teachers are also expected to use language that is less colloquial and more academic when giving formal presentations on a school topic or when participating in oral examinations. So what happens is that starting around the middle school years, academic text across content areas, history, science, convey abstract ideas using precise, concise, and more impersonal language. That tends to be very different from the colloquial language used by children and adults in more informal everyday conversations.

I would like to highlight maybe five key ideas that reveal why language learning is so important for school. And the first idea is that language learning is not complete by age five or six. In fact key language skills which are involved in understanding and writing school text grow precisely during the middle and high school years. But the second idea is that language learning does not unfold naturally and independently from context. In fact a growth in these language skills is highly dependent on opportunities to learn. And so that brings us to the third idea which is language learning more effectively through participation in meaningful interactions. Not an interaction focused necessarily on language learning but on interactions in which language is used to achieve meaningful communication, meaningful connection with someone, meaningful learning. So the fourth idea, and it’s very important for education, is that language learning does not progress homogeneously across kids. There is immense individual variability in language skills throughout middle school and high school. And that finally the fifth idea is that we know that language skills are associated with reading comprehension and learning at school.

Transcript: Paola Uccelli, EdD

What are the implications for educators?

Because teachers and researchers are so expert in using academic language, the challenges of academic text and academic language are so transparent to them and yet they are obscure to children. And so we need to think about how to identify those challenges and those difficult pieces of language to pay attention to them through instruction. We will not be asking teachers to shift their core teaching goals, and not asking them to teach language instead of history or science but just offering them some key support to better communicate and co-construct learning with their students by paying attention to language in promoting a deep understanding.

First we need to understand that as learners grow they need to navigate more social context and use language for an increasing variety of purposes. So they need to continue to learn new ways of using language. And the point that is even more important for education is that we know from research that some learners might be highly skilled in some social contexts. They might be skilled at telling sophisticated narratives or elaborated jokes or reporting sportscasts, but yet they might be less skilled in other contexts such as using language to construct arguments at school. So we need to remember then that language use and language learning vary by context, and that we learn language by participating in specific contexts. We learn to narrate by telling stories, we learn to argue by participating in debates, we learn to use language to explain abstract concepts by doing so. And so not all students have had opportunities to participate in ways of using language that are close to the ways in which language is used at school. And so they might be skilled in many other ways of using language, but not in the ones we particularly expect at school. So as a consequence we need to understand that without addressing the immense variability in students’ language development, schools actually run the risk of maintaining the inequalities that exist in the larger society. That is students who learned the language and literacy practices valued at school as part of their regular life outside of school will continue to have much higher chances of achieving academic success than those who do not have access to such practices outside of school if we don’t address these particular needs.

Reader and Task Considerations

This third dimension of text complexity allows teachers to consider factors related to the individual student as well as to aspects of the reading task at hand. Individual student factors can include things like:

- Motivation

- Background knowledge

- Life experiences

- Cognitive abilities

- Maturity level

For example, a fifth grader who has the reading skills needed for The Hunger Games series may understand the overall plot, but may not be emotionally prepared for the poverty or violence depicted in the story or may miss the deeper political and societal points the author makes.

Similarly, teachers should consider the purpose of the reading assignment and what types of tasks the students will be expected to accomplish when choosing a text. Through carefully constructed small-group activities and class discussions, the teacher can help the fifth grader grasp the underlying themes embedded in The Hunger Games that might not be apparent if the book was read independently.

Did You Know?

College and career readiness standards typically suggest that each grade level’s curricular materials fall within a range of complexity that provides students with exposure to texts of increasing difficulty. When working with a class of middle school students who have diverse reading abilities, teachers need to provide supports for students at lower ability levels so that they can successfully learn from the texts while gradually providing resources to help them move up the continuum of complexity. Likewise, students with strong reading skills must be provided with higher-level reading materials that will offer sufficient challenges and motivation at an advanced level.