What can teachers do to improve students’ comprehension of content-area text?

Page 13: Modify or Qualify Perspectives

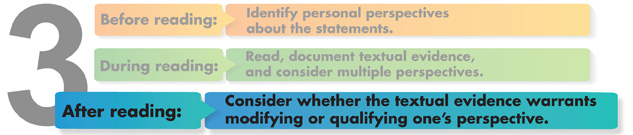

Once they’ve read and reread the text to document evidence relevant to the statements on the guide, it is time for students to reconsider their previous perspectives. During this final step, students learn that sometimes the acquisition of new information or alternate perspectives can alter previously held beliefs, while at other times they can acknowledge a different perspective but still maintain their own.

For this step the students will:

- Review their initial perspectives about the statements.

- Decide whether they still have the same perspective or whether they want to change it. If students change their perspective, they draw an x over their checkmark and then draw a new checkmark under their revised perspective. The x serves as a visual reminder that information from the text significantly influenced their understanding.

- Write a justification for their final perspective in the column titled Reader’s Perspective After Reading. Regardless of whether they changed their perspective, students should still fill out the final column of the guide.

The rationales for the students’ final perspectives should be drawn from both their original perspective and the textual evidence. Their final perspectives may also be influenced by comparing evidence across multiple texts. Initially, the teacher will need to model how to use the information gathered during reading to revisit one’s perspective on an issue. The teacher can demonstrate how one’s perspective may be altered by taking into account things like the source of scientific evidence, the motives of a fictional character, or the historical context of a primary source document. The teacher can also demonstrate that students can maintain their own perspectives while acknowledging—and even respecting—the viewpoints of others. Because linking original perspectives with textual evidence and multiple perspectives can be challenging for some students, they may benefit from hearing how their classmates are aligning or resolving their understandings with what the text presented.

Deborah Reed discusses the opportunities that students have to deepen their understanding of the text during this step (time: 2:15).

Deborah K. Reed, PhD

College of Education, University of Iowa

Director, Iowa Reading Research Center

Transcript: Deborah Reed, PhD

Adolescents can be very opinionated, and to think that they wouldn’t be imposing their own opinions on a text as they’re reading it seems to me to be a missed opportunity to acknowledge them in a way that’s positive and then use it as the basis for at least thinking through: How do you need to present your opinion? What are the ways that strengthen what you have to say? By exploring the way that an author has used textual evidence to support the author’s claim, it’s a chance to look at the author’s craft but in a way that helps the students explore their own thinking and strengthen the way that they present arguments so that they’re not coming from such an emotional place all the time. They have the opportunity during reading and after reading to dig into the textual evidence that’s presented and think about how does that compare with what I thought, with the information that I was bringing into this reading event, and should I be agreeing with this author in this case? Is the author’s evidence compelling enough to convince me to reexamine the way that I thought about this event? Or is the author’s evidence insufficient to really convince me that this point of view is something that I should accept or change my opinion towards? Or can we just agree to disagree? It’s not even that in using the Anticipation-Reaction Guide somebody has to be right and somebody has to be wrong at the end. It’s the value of looking at all of these different perspectives and looking at the strength of the evidence for the different perspectives: the reader’s own, the author’s, and perhaps across text with other authors’ perspectives. What evidence do we have for all of these perspectives? What would the arguments be in each case? And how do they align, how are they different? It’s the value of exploring those perspectives.

In the video below, the teacher guides the students through the process of deciding whether to maintain or modify their original perspectives (time: 4:36).

Copyright © by the Texas Education Agency and University of Texas at Austin. All rights reserved.

Transcript: Anticipation-Reaction Guide After Reading

Narrator: Teacher Gerry Anne Garcia and her students have been using an Anticipation-Reaction Guide for a social studies lesson. This video shows how the class completes the after reading step.

Teacher: We have read our three selections, our three primary sources. We’ve looked at evidence. We have recorded our evidence and our page numbers and paragraph numbers so that if we need to we can go back and find it again. So our last step is we would go back and, based on that evidence, decide whether we want to keep our original opinion, or if now we want to change our opinion. Looking at this first statement: “Native people had a lot to fear from European explorers.” Well, I know that the evidence says whatever their stature they look like giants in our fright. We couldn’t defend ourselves. There were a hundred bowmen. But I still know that the Europeans brought diseases that killed thousands of Native Americans, and they had weapons that the Native Americans had no defenses against. So I’m still going to agree with this statement.

Narrator: The teacher shares her thinking and encourages students to discuss their thoughts about the readings and how the evidence found in the text relates to the statements on the guide.

Teacher: Michael?

Michael: I had it to agree, but reading these documents I changed it to disagree. Because of the Native Americans had a hundred bowmen, and the Europeans had, like, less people, and the Native Americans can get more people to help them. And they were surrounded, the Europeans were surrounded by the hundred bowmen, and they had, like, stronger advantage

Teacher: Remember the process if we’re going to change our answers.

Narrator: The teacher models how to change an opinion on the guide by making an X through the original checkmark and adding a new checkmark in the appropriate column.

Teacher: We want to remember what our original thinking was to see how we might have changed it. Let’s go ahead to the second statement, and look at the evidence and see if now again we want to keep our opinion or if we want to change it. All right, so we have the Spanish gave the natives beads and bells. The natives gave the Spanish each an arrow to show their friendship. Based on that evidence, think about do you want to keep your original opinion whether you agreed or disagreed, or do you now want to change your opinion? So think about it. Did anyone change their opinion after looking at the evidence? José?

José: I changed mine from disagree to agree because, say if the Native Americans were to give them their bows, well, and the Europeans didn’t give them anything, well, it would be hurtful to the Native Americans because, like, they give something for friendship, and they didn’t give anything else so it’s pretty much like saying that you don’t want to be friends with them.

Teacher: Jose, that is an excellent observation, so make sure that you change your original checkmark to an X and then you put your check in the other column. And anyone else that’s now changing their opinion, make sure you do the same thing. Let’s go ahead now with the third statement.

Narrator: The lesson continues as the class considers each statement on the guide. Students deepen their understanding of what they have read, discussing the evidence and deciding if the readings gave them reason to confirm or change their opinions. As the lesson concludes the teacher restates the steps.

Teacher: This Anticipation-Reaction Guide, we used it before reading to get us thinking about what we were going to be reading, during reading so that we knew what to expect, and then the evidence that we would be looking for. After reading, we reviewed the evidence to make sure that we understood what we were reading, and then from there we could decide whether we want to keep our original opinion or if now we want to change it. I want you to make sure that when you come to class tomorrow, you have that Anticipation-Reaction Guide with you and your book in case you need that as well, because tomorrow we’re going to be using this information to write a persuasive essay.

Narrator: The Anticipation-Reaction Guide can be saved and displayed along with other class work as the teacher has done here in the hallway outside the classroom. It provides a visual reference of what students have read and learned.

Teacher: You guys did an excellent job today. I’m really proud of you. This really showed that you were thinking.

(Close this panel)

Note again that the students in the video discuss the reasons for confirming or changing their opinions, but their guide does not have a column for the reader’s perspective after reading. The template provided in this module includes that column.

In her interview, Deborah Reed discusses the feedback from teachers during her research that caused her to insert the Reader’s Perspective columns to the template (time: 1:43).

Deborah K. Reed, PhD

College of Education, University of Iowa

Director, Iowa Reading Research Center

Transcript: Deborah Reed, PhD

We actually added two columns to that Anticipation-Reaction Guide. The first is where the student records the motivation for their agreeing or disagreeing before they read the text, and then the final column where they resolve the way that they think with what they recorded as textual evidence from the process of going through the text and looking for that in relation to the key theme, idea, concept, or statement that’s on the guide. We added those two columns because previously we encouraged teachers to have students share their opinions in class and discuss it and use it as the basis for interacting with students either peer-to-peer within the class, or student-to-teacher so it could be done in small-group or in whole-group in the class. But there wasn’t a formal structure for capturing that. And so in a case where not all students felt comfortable sharing their rationale for agreeing or disagreeing, the teacher didn’t always have the opportunity to go back and provide feedback to students or to examine their rationale before and after reading the text if they didn’t have the opportunity to share it in the class in some way. So by adding that column, it held students accountable for really being able to articulate their rationale, and it gave the teacher a way to check on all students’ work regardless of whether or not they felt comfortable or had the opportunity to share in the full class.

The Anticipation-Reaction Guide below depicts the continuation of the science example from the previous pages and shows where the student’s perspectives were modified based on the evidence gathered from the text.

| Statement | Reader’s Perspective Before Reading | Textual Evidence and Source/Page # | Reader’s Perspective After Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. It is regrettable that animals lose their homes when we cut down trees to mine natural resources. However, it is more important that we obtain those natural resources to make the things we want and need to live. | √ | There were news reports on the great gray owl being endangered by the fire in the Sierra Nevada forest. If we log the trees, it could become extinct. | Trees and plants of the rainforest are home to animals of many different species. To save trees and animals, we can use alternatives to minerals that must be mined so that trees do not have to be cut down to clear the land for mining. | It is not just logging that destroys the animals’ homes, but also clear cutting for building or for mining. | |

| Digmon & Churchill, p. 320 | |||||

| 2. It is better to eat food that is grown close to your town than to buy bananas grown in South America. | √ | We can only buy locally grown bananas at the farmer’s market, and they are very expensive. My sister does not think they taste as good, so we end up wasting more money when she throws them away after a couple bites. | Some food travels thousands of miles to reach our grocery stores. It takes a lot of resources to ship food from another country to the United Sates. If more people support local farms, prices may become more reasonable. | We can support local farms and also grow some of our fruits and vegetables, which will save money. There are community gardens with people who can help us learn. My sister has to make a choice to not waste the food. | |

| Digmon & Churchill, p. 327 | |||||

| 3. Because renewable resources like food, sunlight, and water will replenish themselves, we can use as much as we want. | √ | There are more and more wind turbines being used for electricity because we cannot use up all the wind like we can oil or coal. If we had a wind turbine in our backyard, my dad said it would not cost us anything to run the electricity in our house. | Sometimes renewable natural resources cannot replenish themselves as fast as we are using them. For instance, if there is very little rain and too much water is used, some people can be left with no water at all. | Wind turbines may harm some birds who run into them or who lose their habitats when trees are cut down to install the turbines. Conserving resources is not only about finding alternatives but also about reducing consumption. | |

| Digmon & Churchill, pp. 323, 325 | |||||

| 4. All paper products negatively affect the environment. | √ | To make paper, you have to cut down trees. It creates a problem for endangered animals and it also affects our air because we need the trees to produce oxygen. | Making paper from alternative natural resources like bamboo and recycled cotton can save trees. It can also save the animals that make their homes in trees. | Some alternatives to trees also negatively affect the environment. For example, trees may be cleared to plant cotton, and the crops may be fertilized. Cotton farming can cause soil erosion, and fertilizer can run off into ground water. Processing any material to make paper still requires energy and can create pollution. | |

| Digmon & Churchill, pp. 321, 328 |

The reasoning skills developed through this process are emphasized by college and career readiness standards, such as Anchor Standard 8 from the Common Core State Standards for Reading:

Delineate and evaluate the argument and specific claims in a text, including the validity of the reasoning as well as the relevance and sufficiency of the evidence.

Notice that, in Statement 4 in the example above, the student acknowledges the textual evidence but is still able to put forth a strong argument to justify his original perspective in the final column of the guide.