How can educators recognize and intervene when student behavior is escalating?

Page 5: Agitation

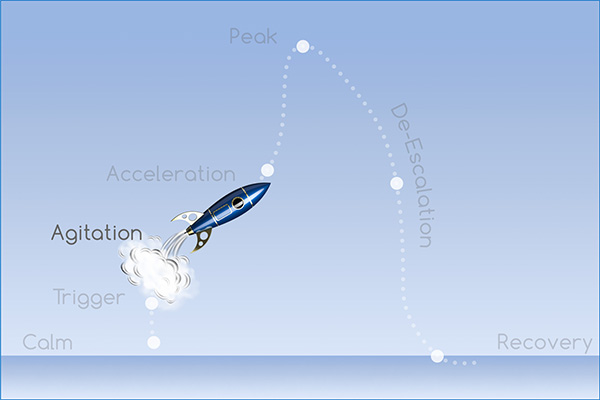

If triggers are not successfully managed, it is likely that a student’s behavior will continue to deteriorate, moving into the next phase—the Agitation Phase. If the cycle is not stopped here, student behavior may continue to escalate, becoming increasingly difficult to manage.

If triggers are not successfully managed, it is likely that a student’s behavior will continue to deteriorate, moving into the next phase—the Agitation Phase. If the cycle is not stopped here, student behavior may continue to escalate, becoming increasingly difficult to manage.

What a Student Looks Like

Agitated behaviors are evidence that the student has disconnected from the learning experience. In general, a student is increasingly off-task and may appear angry, anxious, frustrated, or withdrawn. Students can demonstrate agitation in a number of different ways.

Some students increase behaviors, such as:

- Fidgeting (e.g., tapping hands or feet)

- Pacing

- Shifting from one activity or group to another

- Starting and stopping activities

In contrast, others decrease behaviors, such as:

- Avoiding group work

- Staring off into space

- Putting their head down

- Withdrawing from activities

In this video, note the behaviors that Ava displays during the Agitation Phase (time: 1:59).

Transcript: Agitation Phase

Teacher: Ava, again, please start working on your project.

Ava: What? You didn’t say I couldn’t use this site.

Teacher: I said you should be researching the historical figure that you chose.

Ava: I am researching. Look. [turns tablet so that Ms. Harris can see it]

[Ms. Harris gives Ava a stern look and walks away.]

[ Johanna Staubitz commentary ]

We can see that Ava is continuing to persist in her off-task behavior in this clip. And when Ms. Harris comes over, and that’s a nice job attempting proximity control, she redirects Ava again and it’s positively stated, but Ms. Harris’ irritation is starting to come through in her tone and her facial expression and in the way she walks away. And we see Ava’s agitation in her tone that she’s using toward Ms. Harris, her wish to have the last word, and sort of arguing or looking for the loopholes in the redirection Ms. Harris gave. “I am doing the job you told me,” even though clearly they both know Ava is sort of exploiting the broadness of the instruction to research this historical figure. So she’s increasingly bold with the tablet. These are all signs of agitation. And just keep in mind, that the triggering event was that abrupt transition from an energetic, highly preferred activity that involved her peers to a much less energetic and a much more independent activity. And so the irritated sounding redirect from Ms. Harris doesn’t do anything to ease the difficulty of that transition. It’s kind of separate from it. But what it can do, unfortunately, is really make the problem that needs to be resolved now more complex because now it’s not just the transition that’s the issue. There’s also a power struggle brewing between Ava and Ms. Harris.

Strategies To Implement

During the, often rather long, Agitation Phase, a teacher should carefully select strategies or supports to decrease the student’s agitation. The table lists strategies and tips to best prevent a student’s agitation from escalating. Note that although some of these can be utilized during the Calm Phase, a student who has entered the Agitation Phase will require more targeted support. With this in mind, these strategies should be purposefully and thoughtfully implemented to prevent the student’s behavior from escalating.

| Strategy | Tips |

| Show empathy. |

|

| Use calming strategies. |

|

| Use proximity control with the student. |

x

proximity control In classroom behavior management, a strategy on the part of an instructor to either initiate physical contact or reduce the distance between herself and a student to help the student to control his or her impulses.

To learn more about proximity control, view the following IRIS Fundamental Skill Sheet: |

| Help the student with the task. |

|

| Change the student’s environment. |

|

| Offer instructional choices. |

|

| Provide additional time. |

|

| Share your perspective. |

|

Timing is everything. By using relatively simple strategies, the teacher may be able to defuse (or de-escalate) the situation, and help the student get back on track and return to the Calm Phase. In this video, Ms. Harris intervenes effectively to interrupt the acting-out cycle at the Agitation Phase and helps Ava return to the Calm Phase (time: 2:18).

Transcript: Agitation Phase with De-escalation Strategy

Teacher: Ava, again, please start working on your project.

Ava: What? You didn’t say I couldn’t use this site.

Teacher: I said you should be researching the historical figure you chose for your project.

Ava: I am researching. Look. [turns tablet so that Ms. Harris can see it]

Teacher: Hey, I see that you’re having a hard time transitioning over, so if you want to go ahead grab a sip of water to regroup, you can.

Ava: I think that would help. I need a minute.

Teacher: [hands Ava a pass] Here take a pass. Thank you.

[ Johanna Staubitz commentary ]

We see the same interaction between Ava, who’s off-task, and Ms. Harris, who’s redirecting her. They’re both kind of sounding increasingly touchy and Ava’s getting argumentative. However, this time, Ms. Harris, instead of walking away after making a final redirection, crouches down, gets on Ava’s level, and quietly just makes an observation about the difficulty of that transition. And then she suggests getting a sip of water, which is a way that Ava can take a break without standing out to her peers in a way that she might want to avoid standing out. Instead, it’s something that’s totally innocuous and socially acceptable but also just creates some space between the super fun activity and the less interesting activity. And this space is even more important now that Ava’s, you know, behavior kind of demonstrates she’s agitated beyond Trigger. That break becomes even more important. So again, we start out with the difficulty of the trigger being that transition, but it’s made more complex by these interactions between Ava and Ms. Harris. So, escaping the situation is now also something that’s important. And the sip of water allows her to do that. And there are just important nuances that I hope you’re picking up on in the way Ms. Harris delivered that: getting low, speaking quietly where other people aren’t likely to hear it, and offering a suggestion that is subtle or discreet for the student.

In these interviews, Kathleen Lane first addresses the importance of timing and then describes a situation in which a student quickly became agitated when his academic needs were not met.

Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Professor, Department of Special Education

Associate Vice Chancellor for Research

University of Kansas

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Importance of timing

Once you see symptoms of agitation, there are a couple of different strategies and it’s important that you use these early on in the acting-out cycle, such as during or before the agitation phase, because if they’re used later in the acting out-cycle (like when a student’s really ramping up) it could set the student off and set them up to get into that next stage of the acting-out cycle. But one approach is simply to say, “Hey, it seems like you’re really struggling right now and having a hard time staying on task,” or “How can I help you?” Or “Would you like to go take your assignment and work in another location in the classroom? Do you want to go to the back of the classroom?” Or maybe “Would you like to try working with a partner?” Or maybe there isn’t even that dialogue at all. Maybe you as a teacher just simply notice that the student is struggling at this point, maybe they’re tapping their pencil or their eyes are darting around and they’re looking a little agitated. You might just simply write a little note on a piece of paper saying, “Please help [laughs] a student who’s looking a little agitated. Can you just hold them in your classroom for two minutes? And when that two minutes is up, will you just sign here and send him back to my classroom?” And then you can simply fold that note up, staple it shut, and say, “Hey, Mark, could you do me a favor? Can you run this over to Ms. Smith’s classroom next door?” And then that gives him a way to take a respectful break, to walk away from the situation that’s starting to feel a little bit scratchy for him. And it’s not like you’re saying in front of the whole class, “Hey Mark, it looks like you’re about to lose it, so I need you to leave.” Instead, you’re giving them this respectful way to take a break. But if you were trying that very same strategy, when a student is really gaining momentum and getting to that next phase or even the peak stage, that is exactly the wrong time to exit them from the classroom because they would likely not respond very favorably at all. And that could put them into an unsafe situation. When you’ve got this student who is verbally hostile or physically aggressive, we don’t want to do it at that time. That’s not going to work at all. So we want to think about using that type of strategy and thinking about how to support behaviors before they become out of control. And we want to be cautious that we don’t accidentally reinforce out-of-control behavior. So when you’re seeing somebody that’s struggling, they may not even be realizing yet that they’re having a hard time. And so you don’t ask them. You just simply speak up by saying something like, “All right, guys, at this time, we’re going to go ahead and take a break and we’re going to grab a partner and finish up the last half of this assignment. And with your partner, I’m going to ask you to check your work.” And then you might just run around the classroom numbering them off into one, two, one, two, etc., and then pairing them up with a partner. But the idea there would be we want to shift something in your instruction so that we don’t allow that student to get increasingly uncomfortable with the task at hand. And we don’t necessarily always need it to be a change for the whole class, but that is a simple strategy that we could use. But if you have a student who is disengaging and you realize this isn’t the only student that’s struggling, that could be a way to go. And hopefully, as a teacher, you’re really feeling strong and confident enough in your instruction that you feel like, “Man, I really need to think about a shift that I can make in something that I am doing rather than seeing everything as a within-student challenge.” It could be an instructional problem, and it doesn’t mean that you’re not a great teacher. It just means that in that moment I need to make a shift. And when we think about that interaction pathway between the student and the teacher, we know that what we do shapes the next step with the student. And in this case, you might ask yourself, “What is the smallest shift that I can make right now in how I’m teaching to support students to get on track, to stay engaged, and to limit disruption?” And it’s much easier to do that in either the trigger phase or this agitation phase that we’re talking about. Because at this point, that discrepancy between where the behavior is and where we need it to be is most narrow. And it’s much easier to get students back on track at this point. So timing really matters.

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Student observation

Several years ago, I had the opportunity to be a behavior specialist and my function was to teach teachers about how to manage challenging behaviors and promote very strong, positive relationships between teachers and students and help students to engage in really constructive, appropriate behaviors both within the classroom and outside of the classroom. And in addition to teaching teachers about those strategies, my second part of my job was to assist those situations in which students were having challenging behaviors that the teachers didn’t yet know how to manage. And one day in particular just still sticks out in my mind all these years later. There is a teacher and she was in a self-contained classroom and the teacher was finishing her lunch at her desk, and she then passed out a bunch of papers back to students in the class. And these were papers that had been graded. I was only there to see one student. And when he got all of his papers back, there was a red line through literally every single problem on every single worksheet. And then she said to him, “Now, as soon as you get all these corrected, you can go to the assembly this afternoon. But if you don’t get them corrected, you cannot go to the assembly.” And then she went back and sat down. So he raises his hand and he said like, “I need some help on this. I’m serious. I got every one of these wrong.” And he was obviously upset. And she said, “You just need to try harder.” And he was starting to show signs of frustration. He’s like, “I cannot do this.” And she said, “Well, then you’re just going to have to try.” And she started eating her lunch again. And finally, he escalates in this voice and he’s on the verge of tears. And then he stands up and he rips all the papers and throws them at her in what felt like a million little pieces. And he yells as if he was using a megaphone, “Hello? If I can’t do one, I can’t do 500. Somebody needs to teach me,” which, frankly, at the time I thought was quite profound. And when we took one of the problems that I had found on that torn-up piece of paper, what I learned in looking at some of these, that the pattern was subtracting across zeros. He didn’t understand that concept so that if you were taking like 501 -199, he didn’t know what to do when there was a zero in the tens place. It was simply one correction. And as soon as he learned how to subtract across zero, he had what he needed to do. He can complete the items on the worksheet and he was able to go to the assembly, but he had also earned a detention along the way. And that whole experience really bothered me at the time because his behavior went from what felt like 0 to 100 in a really short period of time, and it really didn’t need to. And I think it created some embarrassment for the teacher and for the student themselves.

Next, Pamela Glenn discusses processes she has in place to prevent behaviors from escalating. Finally, Janel Brown describes calming strategies teachers can use to de-escalate student behavior.

Transcript: Pam Glenn

We’re going to defuse the situation when I can clearly see agitation. We’ve already decided in the room that there are certain spots that you can go without question. We have a signal, and they’ll just give me the signal, whatever it is. And certain students have their own specific signal that they can just go to, regardless of what’s happening. Now there’s some rules to this one. They have to be respectful. They have to be quiet. The class knows, and we’ve built that family. If Kim’s gone to the corner or the center or wherever it is, leave her alone. She needs a minute. You have to come back, and then I’m going to get with you. They know that they’re going to get some kind of “Are you good?” or “Are you all right?” “Do you need a minute?” I think for me, we’ve already established: People get mad, and [laughs] we know that. Recognize when you get mad. What are your triggers and when you get past that, when do you know you’re agitated and it’s going to happen? What can we do to stop that from happening? We talk a lot about using words and just saying, “I cannot” or “No,” or “Leave me alone.” We just know that that person needs a minute. I do a lot of reflecting with the kids. “I hear that you’re upset because of… I would be upset about that, too. What can I do to help you? How can I help you? What do you need from me?” And then I’ll ask them, “What are you going to do? Do you know yet? Do you need a minute so we can figure it out together?” We have a lot of those fists balled up, or somebody’s tapping a pencil or banging their foot, or you see somebody get up. “How can I help you? Because this is not the acceptable behavior. And there’s nothing wrong with being mad. It’s how we deal with it.” So, we do have a lot of those conversations. It usually works. If it doesn’t happen lightning fast. But usually, if you’re vigilant enough to know your students and you know that Johnny struggles with the test, and I know Friday we’re taking the test— we prep that as well. So, we talk a lot about testing, not so that it becomes this big “Oh, my gosh, I’ve got to take a test. I’m going to fail” or “Oh, my gosh, I got to take a test and I have failed them in the past.” “Yes, you have, but now I’m here to help you. And you are so much better than you were. Do I expect A’s? No, I expect you to do your best. So, there’s a lot of realistic expectations, but the bar is still set high. So, you can defuse a lot of those things.

Transcript: Janel Brown

We have to understand that we’re working with kids. Kids come to school with a lot of baggage. You have to have empathy. You have to feel for some of these students because mom and dad might have had a fight before they came to school, and it just really disrupted the start of their day. And if they’re not knowing how to deal with the emotions, you see them getting agitated, “Okay, let’s take a break.” We have what we call brain breaks. Some teachers have what they call a calming corner. They will do breathing exercises, talk about what could you have done differently. Make the kids have ownership for their behavior and come up with ways that they can handle these behaviors differently.

Activity

Watch the following videos, which both illustrate Sam in the Agitation Phase but with different responses from Ms. Harris. Next, from the options provided, select the behavior that signals Sam’s agitation.

Transcript: Video 1—Agitation Phase

[Sam stares into space.]

Teacher: Hey, Sam, are you reading the text? You seem a little distracted.

Sam: Yeah, I’m working on it.

[Sam puts his head down.]

Teacher: Sam, I need to see your eyes on the text.

Transcript: Video 2—Agitation Phase with De-escalation Strategy

[Sam stares into space.]

Teacher: Hey, Sam, are you reading the text? You seem a little distracted.

Sam: Yeah, I’m working on it.

[Sam puts his head down.]

Teacher: Hey Sam, [Teacher places note on Sam’s desk.] I know this text is a little hard but to help get you started I went ahead and wrote down a list of things that I want you to do. Does that help?

Sam: Yeah. That does help actually. Thanks.

- For each video, describe how Ms. Harris responds to Sam’s acting-out behavior.

- Which of Ms. Harris’ responses will most likely de-escalate Sam’s behavior and help him return to the Calm Phase? Explain your answer.

Now that you’ve had a chance to reflect, listen to Johanna Staubitz’s feedback (time: 1:09).

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Assistant Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

In this clip, the activity is continuing, and Sam is still disengaged. He’s withdrawn from the activity, leaning back, looking at the ceiling, and when Ms. Harris checks in on him, he responds in a pretty harsh tone, which is another sign of agitation. In the first video, Ms. Harris responds to Sam’s acting out behavior by approaching him and observing that he seems a little distracted and asking, “Are you reading the text?” And when he responds, “Yeah, I’m working on it,” she reacts with a somewhat irritated tone and says, “I need to see your eyes on the text” before she moves away. And in the second video, instead of saying, “I need to see your eyes on the text,” Ms. Harris notices something’s up, crouches down, speaks quietly with Sam, and shares a list of written instructions. And that of course, is much more likely to de-escalate Sam’s behavior. It’s matched to the problem. Reacting in a way—even if you do it nicely, even if you do it in a joking way, or things that work for the same student in other situations—if they’re not matched to the problem, they’re not going to effectively de-escalate it. Written instructions, perfect solution in this situation.