How can school leaders prepare for the changes required to create inclusive school environments?

Page 5: Establish a Sense of Urgency

The first step toward building an inclusive environment is to establish a sense of urgency––to help school staff embrace the need for change on both a rational and an emotional level. When establishing a sense of urgency school leaders need to:

The first step toward building an inclusive environment is to establish a sense of urgency––to help school staff embrace the need for change on both a rational and an emotional level. When establishing a sense of urgency school leaders need to:

-

- Help staff recognize the need for change

- Identify barriers to creating a sense of urgency

Recognize the Need for Change

Principals can help staff recognize the need for change by 1) presenting them with data, 2) highlighting realities currently facing the school, and 3) encouraging self-reflection. A rule of thumb is that 80% of any presentation should address why the school needs to change and only 20% should address how to achieve that change.

Principals can help staff recognize the need for change by 1) presenting them with data, 2) highlighting realities currently facing the school, and 3) encouraging self-reflection. A rule of thumb is that 80% of any presentation should address why the school needs to change and only 20% should address how to achieve that change.

Present data

To establish a sense of urgency, principals might find it helpful to present current school data to confirm or support a need for school change. Three possible organizing questions and the data that can be used to support them are in the table below.

| Who are we? |

Student demographic data | |

| How are we doing compared to others? How are we doing compared to others like us? |

Data in areas such as academics, discipline referrals, attendance, or parental involvement |

Highlight current realities

To establish a sense of urgency for staff not yet convinced that changes are needed (and to strengthen the sense of urgency for those who are convinced), principals may need to highlight current realities facing their school. Principals should point out that ignoring current realities may create a potential crisis (e.g., not meeting AYP, rising discipline referrals) and that making the desired change may help the school avoid such a crisis.

AYP (adequate yearly progress)

Measure by which schools, districts, and states are held accountable for student performance under the No Child Left Behind Act of 2001 (NCLB); AYP is used to determine whether schools are successfully educating their students.

Elaine Mulligan discusses two current realities faced by schools that often create a sense of urgency (time: 0:52).

Transcript: Elaine Mulligan

When your budget is slashed and you have to lose staff, this is a way that you can restructure things to support kids in ways that are actually better for kids. It takes a lot of work, but restructuring for a budget change always takes a lot of work. So budget is one way that can be a spark, and another one is a subgroup who’s really not performing. It may be kids with disabilities, it may be English language learners, or it might even be a particular ethnic group who are just not measuring up, and you’re being looked at for not meeting AYP. So this usually can start that conversation where we need to meet the needs of these students. So we need to look at doing things differently. So it’s coming to it from a negative standpoint. But you got to work with what you have, and what we have are a lot of pressures on schools.

Encourage self-reflection

Principals can help staff recognize the need for change by asking them to reflect on and honestly answer questions about their school, such as:

- Do you believe that every student has the ability to grow and learn?

- Are all students, including those with disabilities and with diverse cultural or linguistic needs, integral members of the learning community? If so, in what ways do all students benefit?

- Do all teachers embrace a shared philosophy in which all members of the learning community (students, parents, and staff alike) are valued? If so, in what ways do all teachers benefit?

- Are we preparing all of our students to be college- or career-ready?

Barriers to Creating a Sense of Urgency

As part of their effort to foster a sense of urgency, principals should identify and discuss with their staff what beliefs, ideas, and practices might hinder the change effort. Some principals conduct informal surveys to identify the current beliefs, ideas, and practices of the staff. Through these data, principals can make themselves aware of barriers to creating a sense of urgency about inclusion. These may include:

- Low expectations and standards for students, especially those with disabilities and English learners. The existence of this barrier is supported by a study conducted by America’s Promise Alliance, which found that more than two-thirds of high-school teachers surveyed do not believe that all students can meet high academic standards.

- Teachers’ belief that student’s ability to learn is innate and fixed and, therefore, cannot improve as a result of hard work and effort. This mindset often leads to teachers’ low expectations for students’ performance.

- General education teachers’ belief that they cannot adequately meet the needs of all students, especially those who require additional supports

- Teachers’ belief that they are only responsible for students in their own classrooms

- Teachers’ negative attitudes about inclusion

- The perception that there is insufficient time or resources to make changes

Resistance, reluctance, and skepticism are normal and predictable reactions to any kind of major change effort in a school. And though these forms of opposition might seem like significant barriers, principals can actually use them to their advantage. In general, principals should confront resisters in a straightforward, timely, and respectful manner; approach them about their concerns in a non-threatening way; and ask them for ideas about resolving the concerns they have with the change effort. Some prevailing myths related to educating students with disabilities in the general education classroom often serve as barriers to change. Principals who have the facts are prepared to dispel myths. Click on each myth below to learn the facts.

Fact: The intent of inclusion is not to “dump” students but to meet the needs of every student in the least-restrictive environment. Most students with special learning needs can be successful in the general education classroom with appropriate supports and services. In an inclusive classroom, the general education teacher collaborates with and receives support from other educational professionals (e.g., special education teacher, related service providers).

least-restrictive environment

One of the principles outlined in the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act requiring that students with disabilities be educated with their non-disabled peers to the greatest appropriate extent.

Fact: Federal law requires that students with disabilities are provided the services and supports that they need to succeed in school. In fact, through strategies such as flexible scheduling, collaboration among special and general education teachers, and partnering with families, students may receive higher quality services and supports in an inclusive environment.

Fact: Inclusion doesn’t mean that students must spend all day in a general education classroom. The amount of time is determined by the student’s individual needs. The focus should be that students with disabilities have the opportunity to learn, along with their peers, the skills typical of a given age group.

Fact: Students with and without disabilities have the opportunity to interact with one another and can build long-lasting and meaningful friendships. In inclusive environments, students with and without disabilities who are taught to treat others with kindness, compassion, and fairness become more comfortable with and less fearful of one another.

Fact: Research has demonstrated that all students in inclusive classrooms benefit academically. All students’ learning needs are met when teachers have high expectations for all students and employ inclusive practices such as collaborative teaching arrangements and individually tailored learning.

Fact: In inclusive schools, roles are redefined so that teachers no longer work in isolation. There is an organizational shift from individual teachers being responsible for their own students to a team that works collaboratively to meet the needs of all students.

Adapted from NIUSI, Misperceptions About Inclusive Schools and The Handbook of Inclusive Education for Educators, Administrators, and Planners: Within Walls, Without Boundaries (2004).

Matt Montoya created an inclusive school environment at Pima Butte Elementary School. Listen as he talks about the barriers he experienced trying to create a sense of urgency (time: 0:51).

Matt Montoya

Principal, Pima Butte Elementary School

Arizona

Transcript: Matt Montoya

Creating that urgency or that need to really make that happen was somewhat difficult with some of the staff members. There’s always staff members that are very hesitant to change. They’ve had their lesson plans done, and they’re ready to go for the following school year and probably the school year after that. So it was more difficult for some of those veteran teachers who were set in their ways. But getting parents on board was also a challenge. The way that it was was working for them, and they were comfortable with that, then getting people out of their comfort zone was probably the biggest challenge and just always bringing back as much data and research that I could find. I think that that probably helped me win over a good handful of parents as getting their child out of that special ed classroom.

Research Shows

- A national survey of 400 general education teachers and 400 special education teachers indicated that only 37% of general education teachers and 59% of special education teachers reported that they felt very prepared to teach students with disabilities in accordance with a state standards-based curriculum.

(Voltz & Collins, 2010) - A survey of teachers’ attitudes on inclusion conducted with 343 teachers in a rural school district revealed that, on average, more than 70% of them expressed negative feelings or uncertainty about inclusion.

(Hammond & Ingalls, 2003) - A synthesis of the research from 1996 through 2010 demonstrated that general education teachers report that they do not have adequate time, training, or support to instruct students with disabilities in their classrooms.

(Scruggs & Leins, 2010)

To build a sense of urgency about creating an inclusive school environment, Ms. Lawrence shares several things with faculty and staff over several weeks:

To build a sense of urgency about creating an inclusive school environment, Ms. Lawrence shares several things with faculty and staff over several weeks:

- Reading data for the last two years

- Discipline referral data for the last two years

- The director’s concern regarding the reading data

- The possibility of Central Middle not meeting AYP

- Her encounter with Tim, a former student

- Important details from her conversation with the principal at Monet High

Reading Data for the Last Two Years

| Central Middle School Reading Scores | ||||||||

| YEAR ONE | YEAR TWO | |||||||

| % Below Proficient | % Proficient | % Advanced | % Tested | % Below Proficient | % Proficient | % Advanced | % Tested | |

| All Students | 24 | 47 | 29 | 100 | 19 | 51 | 30 | 100 |

| White | 15 | 44 | 41 | 100 | 11 | 44 | 45 | 100 |

| Hispanic | 29 | 50 | 21 | 99 | 23 | 57 | 20 | 100 |

| African American | 33 | 52 | 15 | 100 | 25 | 57 | 18 | 100 |

| Native American | 18 | 50 | 32 | 100 | 11 | 50 | 39 | 100 |

| Asian/ Pacific Islander | 13 | 34 | 53 | 100 | 6 | 38 | 56 | 100 |

|

|

||||||||

| Economically Disadvantaged | 33 | 55 | 12 | 100 | 25 | 56 | 19 | 100 |

| Students with Disabilities | 54 | 36 | 10 | 95 | 60 | 33 | 7 | 97 |

| Limited English Proficient | 30 | 57 | 13 | 99 | 29 | 54 | 17 | 100 |

Adapted from the Tennessee Department of Education

| Average Reading Scores for the District | ||||||||

| YEAR TWO | ||||||||

| % Below Proficient | % Proficient | % Advanced | % Tested | |||||

| All Students | 12 | 48 | 40 | 100 | ||||

| White | 8 | 45 | 47 | 100 | ||||

| Hispanic | 19 | 53 | 28 | 100 | ||||

| African American | 23 | 57 | 20 | 100 | ||||

| Native American | 12 | 50 | 38 | 100 | ||||

| Asian/ Pacific Islander | 4 | 32 | 64 | 100 | ||||

|

|

||||||||

| Economically Disadvantaged | 19 | 56 | 25 | 100 | ||||

| Students with Disabilities | 45 | 42 | 13 | 97 | ||||

| Limited English Proficient | 26 | 53 | 21 | 100 | ||||

(Close this panel)

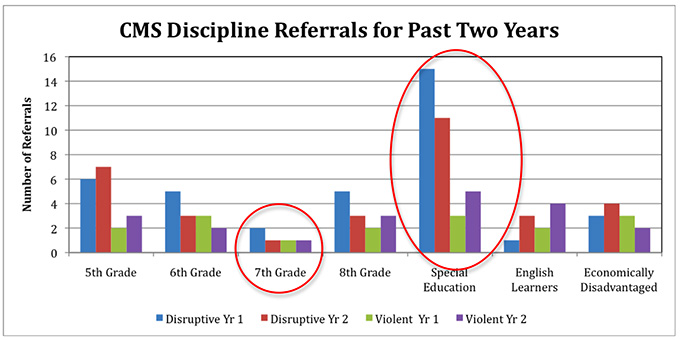

Discipline Referral Data

As she reviews the discipline data for the last two years, Ms. Lawrence notes that the seventh graders received fewer discipline referrals than any other grade level. She also observes that the special education students received more discipline referrals than any other group of students.

Additionally, she conducts an informal survey to assess whether teachers believe there is a problem that requires change.

Ms. Lawrence spoke to 20 of the 36 teachers at Central Middle School. Of the 20 teachers,

- 75% felt that the school could do more to improve the reading skills of all students, particularly those with disabilities.

- 50% felt that by focusing on students with disabilities, the entire school would benefit.

- 35% felt there were risks involved in focusing on students with disabilities (such as that the effort would take too much time or cost too much money) and that such risks would have to be addressed before the school would be successful at this endeavor.

- 40% felt that they did not have the skills to teach students with disabilities.

- 25% expressed negative attitudes about inclusion.

- 95% felt that it was appropriate to present this problem to school personnel.

The reactions of her staff and additional conversations with Principal Sherman in mind, Ms. Lawrence concludes that a sense of urgency does in fact exist. She decides to move forward with creating an inclusive school environment.

Activity

It’s your turn to practice establishing a sense of urgency for your school related to inclusion. If you are not currently a principal, you can consult your state department of education’s website to choose a school.- Examine existing school data (e.g., student performance data, school discipline data). Compare your school’s data to district or state data.

- Identify a gap or problem area related to one of the student subgroups at your school that you feel needs to be addressed.

- Create a survey of five to six questions to determine whether school personnel agree that the problem you have identified needs to be addressed. Conduct this survey with a sample of at least 20% of your school personnel.