Classroom Behavior Management (Part 2, Elementary): Developing a Behavior Management Plan

Developed specifically with primary and intermediate elementary teachers in mind (e.g., K-5th grade), this module reviews the major components of a classroom behavior management plan (including rules, procedures, and consequences) and guides users through the steps of creating their own classroom behavior management plan (est. completion time: 2 hours).

Although not required, we recommend first completing the following IRIS Module:

Work through the sections of this module in the order presented in the STAR graphic above.

Related to this module

Copyright 2026 Vanderbilt University. All rights reserved.

Challenge

Review the movie below and then proceed to the Initial Thoughts section (time: 1:41).

Transcript: Challenge

Classroom Behavior Management (Part 2, Elementary): Developing a Behavior Management Plan

For the past two years, Ms. Amry had been working as a substitute teacher in upper elementary classrooms while completing her degree. She enjoyed subbing and had a positive experience overall. Now that she has graduated and been hired as a third-grade teacher, she’s quickly realizing that she took some things for granted, like the rules and routines that were already in place. For the most part, the students understood the expectations and there were few behavioral issues. But as a teacher in her own classroom, she’s having a hard time getting things to run smoothly. Even after a month of school, her students have difficulty completing routine tasks. For example, something as simple as lining up for recess has become a time-consuming activity: some students blatantly ignore directions while others take advantage of this opportunity to talk loudly or goof off. One student even accused her of being unfair after she reprimanded them for not lining up correctly. Ms. Amry is frustrated and eager to get things on track, but she’s unsure how to get her classroom to run smoothly.

Here’s your challenge:

What should teachers understand about effective classroom behavior management?

How can teachers develop a classroom behavior management plan?

For more resources about evidence-based instructional and behavioral practices, visit iris.peabody.vanderbilt.edu or iriscenter.com.

Initial Thoughts

Jot down your Initial Thoughts about the Challenge:

What should teachers understand about effective classroom behavior management?

What should teachers understand about effective classroom behavior management?

How can teachers develop a classroom behavior management plan?

When you are ready, proceed to the Perspectives & Resources section.

Perspectives & Resources

Objectives

By completing this module and the accompanying activities, the learner will be able to:

- List the core components of a comprehensive classroom behavior management plan

- Describe the key features of each of those components

- Understand how to develop, teach, and implement these components

- Consider how culture influences student and teacher behavior

- Develop the components of a comprehensive classroom behavior management plan in a culturally respectful and sustaining manner

- Develop a personalized comprehensive classroom behavior management plan

Standards

This IRIS Module aligns with the following licensure and program standards and topic areas. Click the arrows below to learn more.

CEC standards encompass a wide range of ethics, standards, and practices created to help guide those who have taken on the crucial role of educating students with disabilities.

- Standard 2: Learning Environments

The DEC Recommended Practices are designed to help improve the learning outcomes of young children (birth through age five) who have or who are at-risk for developmental delays or disabilities. Please note that, because the IRIS Center has not yet developed resources aligned with DEC Topic 8: Transition, that topic is not currently listed on this page.

Environment

- E1. Practitioners provide services and supports in natural and inclusive environments during daily routines and activities to promote the child’s access to and participation in learning experiences.

- E2. Practitioners consider Universal Design for Learning principles to create accessible environments.

- E3. Practitioners work with the family and other adults to modify and adapt the physical, social, and temporal environments to promote each child’s access to and participation in learning experiences.

- E4. Practitioners work with families and other adults to identify each child’s needs for assistive technology to promote access to and participation in learning experiences.

- E5. Practitioners work with families and other adults to acquire or create appropriate assistive technology to promote each child’s access to and participation in learning experiences.

- E6. Practitioners create environments that provide opportunities for movement and regular physical activity to maintain or improve fitness, wellness, and development across domains.

Instruction

- INS1. Practitioners, with the family, identify each child’s strengths, preferences, and interests to engage the child in active learning.

- INS2. Practitioners, with the family, identify skills to target for instruction that help a child become adaptive, competent, socially connected, and engaged and that promote learning in natural and inclusive environments.

- INS3. Practitioners gather and use data to inform decisions about individualized instruction.

- INS4. Practitioners plan for and provide the level of support, accommodations, and adaptations needed for the child to access, participate, and learn within and across activities and routines.

- INS5. Practitioners embed instruction within and across routines, activities, and environments to provide contextually relevant learning opportunities.

- INS6. Practitioners use systematic instructional strategies with fidelity to teach skills and to promote child engagement and learning.

- INS7. Practitioners use explicit feedback and consequences to increase child engagement, play, and skills.

- INS8. Practitioners use peer-mediated intervention to teach skills and to promote child engagement and learning.

- INS9. Practitioners use functional assessment and related prevention, promotion, and intervention strategies across environments to prevent and address challenging behavior.

- INS10. Practitioners implement the frequency, intensity, and duration of instruction needed to address the child’s phase and pace of learning or the level of support needed by the family to achieve the child’s outcomes or goals.

- INS11. Practitioners provide instructional support for young children with disabilities who are dual language learners to assist them in learning English and in continuing to develop skills through the use of their home language.

- INS12. Practitioners use and adapt specific instructional strategies that are effective for dual language learners when teaching English to children with disabilities.

- INS13. Practitioners use coaching or consultation strategies with primary caregivers or other adults to facilitate positive adult-child interactions and instruction intentionally designed to promote child learning and development.

InTASC Model Core Teaching Standards are designed to help teachers of all grade levels and content areas to prepare their students either for college or for employment following graduation.

- Standard 2: Learning Differences

- Standard 3: Learning Environments

When you are ready, proceed to Page 1.

Page 1: Creating a Classroom Behavior Management Plan

Behavior management can be challenging for elementary teachers of any experience level, but it’s often especially so for new teachers like Ms. Amry. Although most behavioral issues are minor disruptive behaviors such as talking out of turn or being out of one’s seat without permission, occasionally students engage in more serious behaviors like defiance, verbal threats, or acting out.

Behavior management can be challenging for elementary teachers of any experience level, but it’s often especially so for new teachers like Ms. Amry. Although most behavioral issues are minor disruptive behaviors such as talking out of turn or being out of one’s seat without permission, occasionally students engage in more serious behaviors like defiance, verbal threats, or acting out.

disruptive behavior

glossary

The good news is that many disruptive behaviors can be minimized, or even avoided altogether, if teachers consistently implement comprehensive classroom behavior management. Getting an early start can help, too. The more time teachers spend addressing behavior management before school starts, the fewer behavior problems they are likely to contend with during the school year.

For Your Information

Disruptive behaviors can result in:

- Lost instructional time (according to some sources, up to 50%)

- Lowered academic achievement for the disruptive student and peers

- Heightened teacher stress and frustration

- Decreased student engagement and motivation

- Inequitable and disproportional disciplinary referrals

- Greater teacher attrition

Before they can begin to create a comprehensive behavior management system, teachers must have an understanding of the key concepts related to behavior and of foundational behavior management practices. If you have not already done so, we recommend that you visit the first IRIS Module in the behavior management series to learn more about each of these all-important topics.

Once teachers feel comfortable with these key concepts and foundational behavior management practices, they are prepared to create a comprehensive classroom behavior management plan (subsequently referred to as a classroom behavior management plan). This plan should be thoughtful and intentional, and it should contain the core components described in the table below.

| Classroom Behavior Management Plan | |

| Core Components | Definition |

| Statement of Purpose | A brief, positive statement that conveys to educational professionals, parents, and students the reasons various aspects of the management plan are necessary |

| Rules | Explicit statements of how the teacher expects students to behave in her classroom |

| Procedures | A description of the steps required for students to successfully or correctly complete common daily routines (e.g., arriving at school, going to the restroom, turning in homework, going to and returning from recess, transitioning from one activity to another) and less-frequent activities (e.g., responding to fire drills) |

| Consequences | Actions teachers take to respond to both appropriate and inappropriate student behavior |

| Crisis Plan | Explicit steps for obtaining immediate assistance for serious behavioral situations |

| Action Plan | A well-thought-out timeline for putting the classroom behavior management plan into place. It includes what needs to be done, how it will be done, and when it will be accomplished. |

As they develop these components, teachers should give them proper and serious consideration in order to minimize the need for subsequent revision, as well as to avoid the need to reteach them to their students in the event they were not clearly articulated in the first place. That said, the components of a behavior management plan are not written in stone. They can and should be revised or adjusted as circumstances dictate.

Listen as Lori Jackman discusses how a classroom behavior management plan can help a teacher enter the classroom with confidence. Next, Melissa Patterson talks about the importance of being flexible and making changes to the plan as needed.

Lori Jackman, EdD

Anne Arundel County Public Schools, retired

Professional Development Provider

(time: 0:42)

Transcript: Lori Jackman, EdD

For an individual teacher who’s just been hired to be able to walk in with a plan of what are you going to do when a kid misbehaves, or what are you going to do for the kids who behave, and what are your expectations, and how are you going to teach it to the kids, so to be able to walk in with that that first day kind of helps them cross the threshold of their classroom a bit more confident than the teacher who’s, like, “I’ll figure it out. I’ll figure it out,” which is what I was told in my teacher prep programs. “Don’t worry. You’ll figure out that discipline thing once you’re there.” I think it gives them an air of calmness when they stand up and introduce themselves to their students those first days of “I’m your teacher, and here’s the plan for helping us all behave.”

Transcript: Melissa Patterson

I think the biggest piece of advice is to have that behavior management plan, but then to make sure that you leave room for flexibility. Because you can create the best plan but then go in and find that it’s not going to work in that specific classroom. So leaving room for flexibility, understanding that things change at the drop of a hat, and that you’re going to have to make changes. But I think the flexibility has to be there for student input as well. You can create a plan, but if you go in and you set all of these hard, concrete rules you’re going to have a lot of student pushback. But if you involve students in creating their environment, you’re going to have a lot more success when the students feel like they have some kind of control over their own space.

Research Shows

Students whose teachers implement the core components of a classroom behavior management plan exhibit less disruptive, inappropriate, and aggressive behavior than do students whose teachers do not use such practices.

(Alter & Haydon, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2017; Simonsen et al., 2015)

Activity

![]() As you work through this module, you will have the opportunity to put each of these components into action. Every time you see the laptop icon displayed on the right, you will be able to create a component of your classroom behavior management plan and save it in the Behavior Plan Tool. When you have finished the module, you’ll be able to print out your plan.

As you work through this module, you will have the opportunity to put each of these components into action. Every time you see the laptop icon displayed on the right, you will be able to create a component of your classroom behavior management plan and save it in the Behavior Plan Tool. When you have finished the module, you’ll be able to print out your plan.

High-Leverage Practices

The practices highlighted in this module align with high-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education—foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. More specifically, these practices align with:

The practices highlighted in this module align with high-leverage practices (HLPs) in special education—foundational practices shown to improve outcomes for students with disabilities. More specifically, these practices align with:

HLP7: Establish a consistent, organized, and respectful learning environment.

HLP8: Provide positive and constructive feedback to guide students’ learning and behavior.

HLP9: Teach social behaviors.

HLPs, which all special education teachers should implement, are divided into four areas: collaboration, assessment, social/emotional/behavioral practices, and instruction. For more information about HLPs, visit High-Leverage Practices in Special Education.

Page 2: Cultural Considerations and Behavior

Culture is a word we use to describe any of the practices, beliefs and norms characteristic of a particular society, group, or place. When cultural practices involve easily observable characteristics such as the clothing people wear, the food they eat, the languages they speak, and the holidays and traditions they celebrate, we often refer to these practices as visible. However, many cultural practices are more subtle: people’s interpersonal relationships, family values, familial roles and obligations, interactions between peers and community members, and beliefs about power and authority. It’s important for teachers to understand that culture can:

Culture is a word we use to describe any of the practices, beliefs and norms characteristic of a particular society, group, or place. When cultural practices involve easily observable characteristics such as the clothing people wear, the food they eat, the languages they speak, and the holidays and traditions they celebrate, we often refer to these practices as visible. However, many cultural practices are more subtle: people’s interpersonal relationships, family values, familial roles and obligations, interactions between peers and community members, and beliefs about power and authority. It’s important for teachers to understand that culture can:

- Influence the behavior of teachers and students alike

- Influence the behaviors and actions that occur daily in the classroom setting

- Affect teacher-student interactions

- Impact the extent to which teachers are able to manage behavior

For Your Information

Race is not synonymous with culture. However, racial identity is the product of social, historical, and political contexts, and thus students’ racial and cultural identities often share many commonalities.

It is also important for teachers to recognize that their students’ cultural practices and beliefs might well be different from their own. These differences, or cultural gaps, frequently lead to disparities in the ways teachers respond to behavior. Click here to review examples that illustrate certain specific perspectives and approaches that might result in cultural gaps.

cultural gap

glossary

| Differing Cultural Perspectives | |

| Respect for authority figures | |

|

Teachers are automatically regarded as an authority figure (based on role/position or age). |

As a new member of the community, teachers must earn respect. |

| Relationships with community | |

|

Teachers are expected to collaborate with family members or community elders. |

Students and families expect teachers to act independently. |

| Interpersonal space | |

|

Standing very close to someone when speaking is seen as violating personal space. |

Standing very close to someone when speaking indicates a close relationship. |

| Eye contact | |

|

Eye contact conveys listening. |

A lack of eye contact indicates deference or respect. |

| Verbal interactions | |

|

Verbally conveying information in a direct and assertive manner is valued. |

Verbally conveying information in an indirect and passive manner is valued. |

| Providing directions | |

|

Providing directions in the form of a question (e.g., “Can you join us for group time?”) implies an expectation to comply. |

Providing directions in the form of a question implies an expectation of choice or an option to decline. |

| Student engagement | |

|

Students who listen and remain quiet are respectfully engaged. |

Students who actively participate are engaged. |

| Family engagement | |

|

Families who participate in school events are considered to be interested and involved in their child’s education. |

There is a clear distinction between the role of the teacher and that of the family: Academics is the sole responsibility of the teachers while families provide instruction on skills and knowledge needed at home and in the community. |

Teachers should identify and anticipate potential cultural gaps that may influence their behaviors and interactions with students. To more effectively do so, teachers should have an understanding of their own culture and their students’ cultures. Click on the tabs below to learn more.

Before teachers can begin to navigate the complexities of the diverse student backgrounds in their classrooms, it is crucial that they take time to examine their own beliefs and cultural practices. Teachers may not realize how much of their daily routines and practices are influenced by their cultural practices and upbringing. From the holidays and traditions they celebrate, to the way they interact with others and show respect to those in positions of authority, many of the choices and actions teachers make each and every day are influenced by culture. These beliefs and actions can affect the way they operate their classrooms, including how they go about creating rules, procedures, and consequences, and execute their classroom behavior management plan.

Listen as Lori Delale O’Connor discusses why it’s important to understand one’s own culture, as well as how the culture in classrooms and schools impacts students.

Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Assistant Professor of Education

University of Pittsburgh School of Education

(time: 2:34)

Transcript: Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

It’s really important to understand one’s own culture and think about the ways that impacts students. I think one of the most important aspects of that is, without the recognition of one’s own culture, we start to see that the practices that we’re engaged in, our ways of being, our ways of knowing as sort of normal. And we may as a result demean ways of being and knowing that are different than ours as abnormal as sub-standard. So understanding one’s own culture allows us to see that culture itself isn’t neutral, that everybody has their own culture and their own ways of understanding, not just people we deem as different than us. And so that supports recognizing the culture of everybody in the classroom, including the teacher. It’s important to recognize that schools themselves have cultures, and classrooms themselves have cultures. Again, it goes back to this idea that when we don’t recognize that there is a culture of a place that has been developed over time and within a specific context, we start to see that as normal or neutral and everything that deviates from that as abnormal, instead of just seeing like, oh, hey, this developed over time and is the product of our expectations, of our ways of being, of our goals and ideas for the purpose of schools and the purpose of education. And those vary across time and space. And I think the culture of schools and classrooms, particularly within the context of the United States, there’s a very strong historical component that often we overlook, that we just sort of accept it as this is the way it is, rather than questioning how did it get this way and does it serve the needs of the teacher, of the building staff, of the students, of their families? Recognizing that every school in every classroom has a culture and that culture arises from the development of school itself within the United States, but also of that particular location is really helpful to recognizing the ways we can change or keep the different practices and policies that serve us well, and we can discard or change the things that aren’t serving us well to reflect the changing culture of the classroom and in the school.

Activity

To gain a better understanding of your own knowledge, attitudes, and practices, as well as to identify areas of strength and growth, complete the Double-Check Self-Assessment. When you are done, click the “Finish” button to get some feedback.

Note: If you have worked through Classroom Behavior Management (Part 1): Key Concepts and Foundational Practices, you may have completed this assessment.

Adapted from “Double-Check: A Framework of Cultural Responsiveness Applied to Classroom Behavior,” by P. A. Hershfeldt, R. Sechrest, K. L. Pell, M. S. Rosenberg, C. P. Bradshaw, and P. J. Leaf, 2009, Teaching Exceptional Children Plus, 6(2).

Students and teachers may have similar cultural backgrounds and experiences, share only certain cultural experiences, or be altogether different from one another. When cultural gaps are present, students may not understand what is expected of them or how to interact with others. Learning about students’ cultures can help teachers:

- Identify areas in which students may need more support and explicit teaching of behavior rules and procedures

- Create rules and consequences that align with students’ cultural beliefs and practices

Following are some examples of how teachers can learn more about their students and their cultural backgrounds, experiences, and practices.

- Instruct students to write an autobiography.

- Have students interview each other about their family’s culture and practices then provide them with an opportunity to share what they learned about their peers with the class. Alternatively, instruct students to interview one or more family member(s) about culture and practices and ask them to share what they have learned with the class.

- Ask students or families for recommendations of books that represent their cultures and languages. Read these books together as a class.

- Encourage students to discuss how their cultural practices or beliefs may differ from how they are depicted in literature and other media.

- Invite family members to teach a lesson or to share something about their culture, traditions, holidays, or cuisine.

Listen as Andrew Kwok discusses the importance of teachers understanding their students’ cultures. Next, KaMalcris Cottrell highlights how her school creates a safe space where students are able to share their beliefs and values.

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of

Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

(time: 1:15)

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

It’s important to understand your students’ culture. Being a good teacher means that you need to understand who you’re going to teach. If you consider many other professions, those who succeed tend to really understand their constituents, and teaching is no different. Teachers need to recognize what makes their students tick and what motivates them and what expectations they may have of themselves and how those expectations can be transferred over into the classroom. And so the more that teachers can invest towards getting to know their students and their cultures, the more that they’ll be able to bring that information into the classroom and be able to apply it in meaningful ways so that their students can engage and participate and feel like a part of that classroom community and feel like they are being integrated and part of the learning process, as opposed to being individuals who are being spoken at and having to do learning one specific way. This opportunity to get to learn about their students opens up a variety of options for expanding their education.

Transcript: KaMalcris Cottrell

A few lessons that I’ve learned instructing or interacting with students from different cultures is to be as open-minded as possible to create a safe space for them to feel like it’s OK to share their different views and culture or their background or activities that their families may participate in that are foreign to me. But, again, if you’re open-minded, I’m always going to learn. And I think our school does an excellent job of providing this safe space. In the mornings, we have a caring community circle, and the teachers invite the students to join this circle and share on certain topics or even just something that the students would like to share that’s important to them. But I believe without this safe space, that sharing can’t take place. We talk about our behavior. What’s the expectation while we’re in the circle. We have the one person speaking. We do have non-verbal signals that the students can show that they agree or that they’ve done the same thing or they’ve had the same experience. We have a quiet hand raised if you would like to ask a question at the end. So I think with these parameters in place for this circle, this structure, this sharing time, it allows students to feel comfortable enough to share their different cultures and backgrounds. In 15 minutes every child has a chance to share, and you can always choose to pass and then at the end we’ll come back around if now you’re comfortable with sharing, you may do that at the end. So it’s very relaxed and nonjudgmental. You can share what you would like to share.

I believe the importance of understanding an individual’s culture is just to continue to give them validity. It’s hard to feel valid if you feel that you’re not understood. So if they are willing to share, I’m willing to learn. And I would hope people feel the same way about my culture. I’m willing to share. And I think if we can see other cultures through their view or from different points of view, it makes us that much stronger of a community.

To learn more about student diversity, view the following IRIS Modules:

Although many different cultures are represented in schools across the country, what is commonly perceived as “appropriate behavior” typically reflects white, middle-class cultural norms and values. These norms are reflected in classroom rules and procedures around behavior, communication, and student participation. Some students (or groups of students) may thrive within a particular school setting because their norms and practices align with these rules and procedures. In other words, they have the cultural capital—the acquired skills and behaviors that are accepted within a group and which give that group an advantage in a given environment. On the other hand, students with different cultural backgrounds may not innately grasp or understand traditional classroom rules and procedures because they do not align with what is considered appropriate or standard behavior in their home or community.

cultural norm

glossary

As noted above, when a student’s culture does not align with that of the classroom, this can result in cultural gaps. Cultural gaps can cause teachers to misinterpret students’ behavior—especially more subjective behaviors (e.g., disrespect, noncompliance)—which can lead to conflict. These conflicts can have a range of effects:

- Students feeling misunderstood or marginalized

- Escalation of misbehavior and aggression

- Higher rates of discipline referrals

- Students leaving school altogether

Let’s explore the effects of teachers misinterpreting student behavior in more depth. Black and Latino students, in particular, are subject to more frequent and harsher discipline compared to their white peers. This holds true starting as young as preschool and continues through high school. Oftentimes, this discipline is the result of subjective understandings of student behavior such as interpreting an action as “rude” or “disrespectful” rather than understanding that the behavior may stem from cultural differences. These subjective interpretations lead to negative outcomes for students that further exclude them from learning opportunities, including higher rates of suspensions, expulsions, and even students leaving school.

Checking in with Ms. Amry

Ms. Amry considers it respectful for her students to make eye contact when she is speaking to them. Jordan, on the other hand, has been taught that making eye contact is disrespectful to adults, and so he looks at the ground when Ms. Amry speaks to him. Ms. Amry’s understanding of culturally based responses is critical to deciphering Jordan’s intent. If the teacher does not understand Jordan’s culture, a seemingly insignificant action like looking at the ground could be misinterpreted as defiance, apathy, or lack of respect and could result in the teacher administering a negative consequence.

Ms. Amry considers it respectful for her students to make eye contact when she is speaking to them. Jordan, on the other hand, has been taught that making eye contact is disrespectful to adults, and so he looks at the ground when Ms. Amry speaks to him. Ms. Amry’s understanding of culturally based responses is critical to deciphering Jordan’s intent. If the teacher does not understand Jordan’s culture, a seemingly insignificant action like looking at the ground could be misinterpreted as defiance, apathy, or lack of respect and could result in the teacher administering a negative consequence.

Research Shows

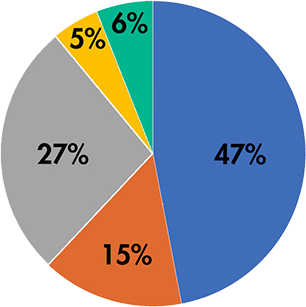

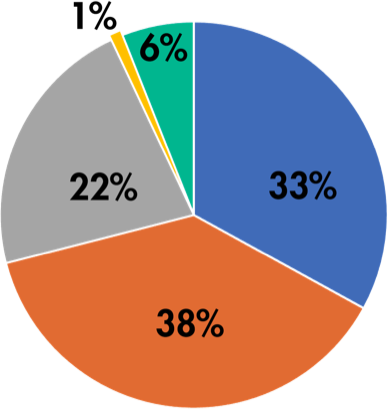

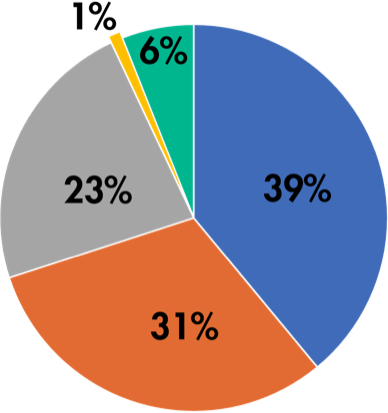

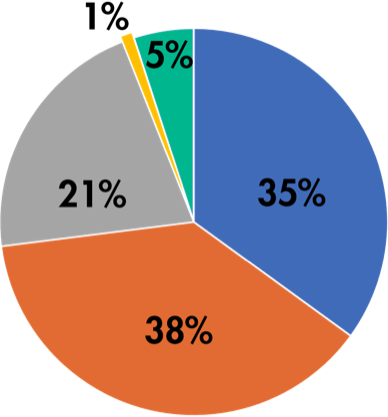

During the 2017–2018 school year, Black students in grades K-12 accounted for approximately 15 percent of total student enrollment. However, Black students were overrepresented in disciplinary actions. They accounted for approximately:

- 31 percent of in-school suspensions (one or more instances)

- 38 percent of one or more out-of-school suspensions (one or more instances)

- 38 percent of all expulsions (with and without educational services)

Students

In-School

Suspensions

Out-of-School Suspensions

Expulsions

Description: Cultural data graphs

The first chart is labeled ‘Students’ and is divided as follows: 47% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 27% Hispanic (gray), 15% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 6% other (green), and 5% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The second chart is labeled ‘In-School Suspensions’ and is divided as follows: 38% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 33% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 22% Hispanic (gray), 6% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The third chart is labeled ‘Out-of-School Suspensions’ and is divided as follows: 39% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 31% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 23% Hispanic (gray), 6% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

The fourth chart is labeled ‘Expulsions’ and is divided as follows: 38% Black/non-Hispanic (orange), 35% white/non-Hispanic (blue), 21% Hispanic (gray), 5% other (green), and 1% Asian/non-Hispanic (gold).

Additionally, data from the 2018–2019 school year indicate that Black students with disabilities ages 3–21 were overrepresented in disciplinary removals—incidences involving a student being taken out of an educational setting for disciplinary purposes (e.g., in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, expulsion, removal to an alternative educational setting, removal by a hearing officer). In the table below, note how the number of disciplinary removals for Black students is twice the average among all racial/ethnic groups and nearly three times the average for White students.

Average Number of Disciplinary Removals Among Students with Disabilities

|

||

| All | White | Black |

| 29 | 24 | 64 |

(Sources: National Center for Education Statistics; U.S. Department of Education, Office for Civil Rights; U.S. Department of Education, Office of Special Education Programs)

When teachers understand how cultural gaps negatively impact some students, they can more effectively develop a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan (e.g., rules, procedures, and consequences). Although the plan should be developed before the school year begins, it is important to be flexible and allow for changes throughout the school year as teachers learn more about their students. Some ways to make the plan more culturally sustaining are to:

culturally sustaining practices

glossary

- Ask for student input — Discuss components of the classroom behavior management plan (e.g., rules, procedures, consequences) with students. This discussion can include:

- Acceptable behavior at home or in their culture

- Fair or appropriate behavior in the classroom that allows everyone to be successful

- Compromises needed to address discrepancies in cultural norms. For example, some cultures prioritize the sharing of resources (e.g., pencils, paper) while others value independent ownership. A good compromise might be to allow both but with criteria for when each is appropriate.

- Seek family input — Learn more about the cultural practices of the student and family and what promotes the student’s success. This information can be gathered formally or informally through:

- Meetings (Meet the Teacher night, parent-teacher conferences)

- Frequent two-way communication (emails, phone calls)

- Build relationships with students — When teachers and students learn more about and develop a mutual respect for each other:

- Teachers gain a better understanding of what students need to engage in class and to succeed

- Students gain a better understanding of why particular rules and procedures are necessary to help the class run smoothly and to help the class succeed

- Encourage relationships among students — When students get to know each other, they are more likely to:

- Understand and respect each others’ differences

- Help one another to learn and grow

Listen as Lori Delale O’Connor discusses cultural capital and what it means for students in the classroom. Next Andrew Kwok discusses the discrepancies that may exist between the school and classroom culture and students’ cultures. Finally, he talks about developing a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan.

Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Assistant Professor of Education

University of Pittsburgh

School of Education

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor

Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

Transcript: Lori Delale-O’Connor, PhD

Cultural Capital

Cultural capital is this idea that students and their families are familiar or are unfamiliar with what is deemed the “legitimate” culture within a society and in particular within a school. So it’s do you know how to engage the way the school expects you to? And if you do you’re rewarded and rewarded in the sense of you might get better grades. You are going to get opportunities because your teachers are going to say, oh, wow, what a great behaved student, what a high-achieving student. And a lot of that stems from not necessarily a student’s ability to do something but their understanding of how school works essentially, and their families understanding of how school works. When I think about families, some great examples are do you know how to contact a teacher in the way that the teacher expects and is deemed appropriate? And you’ll see cultural differences in that. In some cultures, it’s really believed that education is meant to be left to teachers, and there’s a high amount of respect. And so, as a parent, I’m going to trust that you know your job. You’re really good at it. And it would be an insult to you if I came in advocating for my student. Or, similarly, that actually the education is meant to happen between young people and the teacher. And so if there needs to be any intervention or if there needs to be conversation about it, it’s the role of the young person. In white, middle- and upper-class schools, there is a strong expectation that parents know how to intervene on behalf of their children. And the outcome of that often is that families might get what they want. And that might be an intervention in terms of my child needs something else. Perhaps reconsider my child’s grade. And similarly for young people there is an expectation of how you might advocate for yourself. And so they learn to argue in a polite and respectful way for what they want, and they learn to advocate for themselves from a very, very young age. And these sort of things are unstated. And if you are a young person coming from a family where you’re told to be deferent to the educator or to adults in general, and you’re really told not to speak unless you’re asked a question then you’re not going to know to advocate for yourself. And so basically with cultural capital, the idea is that it’s passed through families, and it helps them do better in school. If the ways that families know and value education aligns with the ways that the schools, their young people grow to also know and value education.

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Discrepancies between classroom and students’ cultures

The culture of schools and classrooms is really important for teachers to consider, particularly in thinking about the structures that make up education and schooling. What we already know about the cultural gap within the classrooms between teachers and students, we need to think about ways to alleviate that gap and allow primarily minority students to learn within a predominantly white and female school. The discrepancy means that the faculty and the teachers need to actively consider the environment that students are placed in and then think that it comes from mostly one or two traditional ways of understanding learning but more specifically as it relates to classroom management. One or two specific ways of how to behave and how to act within a classroom or a school environment, those sort of ways of acting and behaving does not necessarily always align with how other cultures think about or process appropriate behavior. The idea of misbehavior has multiple different definitions, and the way it can look in one certain classroom or within one certain school can differ, and without specifically aligning that or coming to an understanding of what that can look like there’s going to be discrepancies. And for teachers to be more culturally responsive, they need to understand that there are traditional structures within the school and within the classroom that need to be addressed, whether it needs to be changed directly or incorporate students’ voices and their opinions and perspectives so that the students can succeed within that environment.

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Developing a culturally sustaining classroom behavior management plan

Many teachers are often wanting to establish a certain type of classroom without any sort of flexibility. They have an idea of the classroom, and they want to stick to that and make all students within that classroom abide by that particular structure. Beginning teachers in particular, they’re often focused on maintaining authority and being able to essentially control the kids, be able to have them listen and do what they want to do in order to follow through on their lesson plan. But that’s not necessarily culturally responsive in the sense that it’s not necessarily considering what the students need in order to succeed within the classroom. So in order to consider a culture within these behavior management plans, often the easiest way to integrate that is through student input, being able to allow for opportunities for students to help create some of the structures, whether it’s the rules or procedures, and thinking about what it is that not only allows the teacher to succeed in the classroom but also what it takes for those individual students to engage with the material and be able to be as successful as they want in the classroom.

Other ways that behavior management plans can be more culturally sustaining would be to have the teacher build relationships with the students or to have the students have positive interactions with one another. In order to incorporate student input, the teachers really need to know their students and be able to understand what helps them to learn. And so, in order to do that, teachers often just rely on a beginning-of-the-year get-to-know-you paper, but students’ needs are individual and they are evolving and developing over the course of the year, and so the teacher constantly needs to check in and to get to know them and even share bits about themselves with the students so that they can build a strong bond that can then allow the teacher to understand what allows those students to engage with the material. And the same goes for allowing opportunities for the students to build relationships with each other, to get to know one another so that they can collectively learn, as well. It’s difficult for the teacher to be able to differentiate one lesson 20, 30 different ways for each individual within the classroom, but if they can think about collective similarities across students and see how they interact with one another and how they can help one another to learn and grow, that will allow for opportunities to change and adapt these structures within the system. Then the last bit would be to also consider families and community and peer teachers in considering additional factors that can help teachers succeed in building an effective classroom management plan.

Keep in Mind

Many classrooms include English learners (ELs) who are in the early stages of learning English or are still acquiring academic English language skills. What may appear as noncompliance to a verbal/written instruction or rule may in fact be a language misunderstanding. To support ELLs in understanding classroom rules and procedures, teachers should:

English learner (EL)

glossary

- Model appropriate behaviors and expectations

- Use pictures or other graphics to support language comprehension

- Use positive statements (e.g., “You can sit down.”) instead of negative statements (e.g., “Don’t get up from your seat.”)

- Use peers/school staff who speak the student’s home language to help explain rules and procedures

- Provide the rules and procedures in the student’s home language (when possible)

To learn more about English learners, visit the following IRIS Module:

For more information on cultural influences on behavior, view the following IRIS Module:

Page 3: Statement of Purpose

An effective classroom behavior management plan begins with a statement of purpose—a brief, positive statement that conveys the reasons various aspects of the management plan are necessary. You might think of this like a mission statement that guides the goals, decisions, and activities of the classroom. Because it lays the foundation for the rest of the plan, the statement of purpose should be the very first thing the teacher writes. The four criteria below are key to communicating the statement of purpose to education professionals, parents, and students.

An effective classroom behavior management plan begins with a statement of purpose—a brief, positive statement that conveys the reasons various aspects of the management plan are necessary. You might think of this like a mission statement that guides the goals, decisions, and activities of the classroom. Because it lays the foundation for the rest of the plan, the statement of purpose should be the very first thing the teacher writes. The four criteria below are key to communicating the statement of purpose to education professionals, parents, and students.

| Criteria | Description |

| Focused |

|

| Direct |

|

| Positive |

|

| Clearly Stated |

|

Andrew Kwok discusses how a teacher can create a statement of purpose that is culturally respectful and responsive. Next, KaMalcris Cottrell describes her classroom’s statement of purpose.

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of

Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

(time: 0:50)

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

In terms of a statement of purpose, all teachers should think about what they want to accomplish in the classroom, but they also need to consider what the students and the parents and others, the actual constituents of the classroom, want to accomplish as well. And there should just be a merging of those goals and objectives, as opposed to having the teacher create something and assuming that one box fits all students. Being able to allow space for it to incorporate the individuals that it’s working with will allow it to be more respectful and responsive, as opposed to creating a definitive statement that does not allow for the flexibility of those who it is currently teaching.

Transcript: KaMalcris Cottrell

My classroom statement of purpose aligns with our school-wide statement of purpose. It gives us our expectations for the day from the student side and from the teacher side. And this mission statement covers our four Be’s: respectful, responsible, ready, and safe. There are the things that we’re saying we’re going to be every single day. And with this in place, I also incorporate myself into this. I tell the students, I will be respectful, I will be safe, I will be responsible, and I’ll be ready. So when you come to my group, I’m going to be ready for you, and we’re going to be responsible, and we’re going to work on the skills that we need to work on. And I think this is important because this is throughout our entire school. So even when we come together as an entire school body, everyone knows what the four Be’s are. So if we say, “I will be ready,” students start to check themselves. Oh, am I ready? Am I sitting safely? Is my voice off? Am I paying attention? Are my eyes on the speaker? So just the four cue words. But I think it also covers individual work in the classroom. It covers group work in the classroom. It also covers outside of the classroom.

Checking in with Ms. Amry

Ms. Amry developed the statement of purpose below. Review it and determine whether or to what extent it is focused, direct, positive, and clearly stated.

Ms. Amry developed the statement of purpose below. Review it and determine whether or to what extent it is focused, direct, positive, and clearly stated.

Our classroom is a safe, positive place where everyone works together, is creative, and is respectful. All students will participate in learning and do their very best.

| Focused |

|

| Direct |

|

| Positive |

|

| Clearly Stated |

|

Research Shows

A statement of purpose (or mission statement) is an important tool for shaping practice and communicating core school or classroom values. When stated in a clear, succinct, and positive way, this statement serves as a foundation for developing a classroom behavior management plan and cohesively ties the components of the plan together.

(Algozzine, Audette, Marr, & Algozzine, 2005; Stemler, Bebell, & Sonnabend, 2011)

Activity

![]() Now it’s your turn to create a statement of purpose. You can develop it for your classroom (current teachers) or for the grade level you hope to teach someday (future teachers).

Now it’s your turn to create a statement of purpose. You can develop it for your classroom (current teachers) or for the grade level you hope to teach someday (future teachers).

Click here to develop your own statement of purpose.

Note: If your school has a school-wide statement of purpose or mission statement, be sure your classroom statement aligns with it.

Page 4: Rules

Now that the teacher has created a statement of purpose, she should consider how she expects her students to behave. These behavior expectations can be defined as broad goals for behavior. Because behavior expectations are often abstract for young students, the teacher should create rules to help clarify their meaning as they are applied within specific activities and context. Rules are explicit statements that define the appropriate behaviors that educators want students to demonstrate. Rules are important because they:

Now that the teacher has created a statement of purpose, she should consider how she expects her students to behave. These behavior expectations can be defined as broad goals for behavior. Because behavior expectations are often abstract for young students, the teacher should create rules to help clarify their meaning as they are applied within specific activities and context. Rules are explicit statements that define the appropriate behaviors that educators want students to demonstrate. Rules are important because they:

- Allow students to monitor their own behavior

- Remind and motivate students to behave as expected

Although rules vary across classrooms, they often address a common set of expected behaviors:

- Be respectful

- Be responsible

- Be ready

- Be safe

Developing Rules

For Your Information

Classroom rules should align with school-wide behavior expectations. Creating rules that apply in the classroom as well as other parts of the school (e.g., Use inside voices) will also help reduce the number of individual rules students need to remember.

When developing classroom rules, elementary teachers should make sure they are easy for students to understand and remember. For this reason, teachers should limit the number of rules to no more than five. Additionally, teachers should make sure the rules adhere to the guidelines in the table below. Examples and non-examples are provided.

| Guidelines | Example | Non-Example |

| Convey the expected behavior | Follow directions. | Be respectful. |

| State positively | Use safe speed. | No running. |

| Use simple, specific terms | Keep your hands and feet to yourself. | Respect the physical and psychological space of peers. |

| Make observable and measurable | Be in your seat when the bell rings. | Be ready when class starts. |

In addition to adhering to these guidelines, teachers need to ensure that their rules are culturally sustaining. To do this, teachers can:

- Create classroom expectations with the values of students, families, and their communities in mind

- Create rules and expectations that foster learning for the diverse group of students in the classroom

- Seek student input to ensure rules address the variety of student backgrounds

- Be open with students about differences in school rules and expectations and those in the home or community

- Consult with cultural liaisons and community outreach specialists who have personal knowledge and understanding of the cultures represented in the school

Listen as Andrew Kwok discusses some of these strategies in more detail. Next, he discusses strategies for ensuring that rules are not culturally biased.

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

Strategies to ensure that rules are culturally sustaining

(time: 1:27)

Strategies to ensure that rules are not culturally biased

(time: 3:10)

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Strategies to ensure that rules are culturally sustaining

One thing that teachers can do is spend time to define different words. So the word “respect,” what does that mean for each individual, and how can those different definitions be shared and encapsulated within a specific rule? One person may define respect as keeping your hands and feet to yourself, whereas another student can define it as in not talking while the teacher is talking. And so being able to hear all of the students’ beliefs and being able to create something that is comprehensive enough that all students feel heard throughout. Another word could be “engagement.” What does it look like for these students to engage? Some students may want to shout out their answers. Other students may want raised hands. And so providing spaces for each of those types of students to be able to participate in the activity without it being a detriment to others and being able to find compromises throughout that allow all students to feel like they’re in a safe learning environment so that they can learn and grow as much as possible. Students often just want to be heard, and I think the teacher has an obligation to provide the students voice in the classroom and be able to build an environment based off of their needs, rather than focusing specifically on what the teacher wants to accomplish.

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

Strategies to ensure that rules are not culturally biased

Oftentimes, I see rules that are biased when they define structures only one way, whether it’s the idea of engagement or learning or respect or interactions. It’s only when the teacher accounts for the students and thinks about multiple ways for things to be accomplished do I then consider things to be a little bit more culturally considerate. But beginning teachers in particular, they want to establish one type of authority, one type of control. And in order to do that, the students must follow one way of doing it. Oftentimes, that’s the way of being silent, quiet at your desk with only the teacher’s instruction being heard and being the one to delegate information. It may be easier in the sense that it’s quiet and silent and what the teacher had always envisioned. But just because they’re silenced doesn’t mean students are learning. They need to really think about what it is the students need to succeed and to engage with the material. I think students can share what it takes for them to engage and to learn. But I think if you have the opportunity to also ask them, what does it take for others within your classroom to learn so that they can kind of step outside of themselves and really consider their peers and being able to recognize that most students are pretty honest in saying, “Well, I know for me I need this, but I know other people, they may need something a little bit different.” So is there a way to bridge and compromise those sort of differences? I think another way would be to have the teacher consider certain times that prioritize certain structures and other times that prioritize other structures. So the idea of engaging in classroom, some students like to yell out the answers because to them they’re so excited they have it they just cannot wait, as opposed to others who want the opportunity to raise their hand and be able to be called on. I think there’s value in both, but I think there is a time and place for both. And so the teacher can preempt lessons or discussions and saying, “At this time, we are going to accept hands raised only” or “At this time, I just want to hear you shout out the different answers.” I think that allows students to be able to feel accepted in certain places. And I think the teacher also has the opportunity to share with the students the pros and cons of both types of modalities, because to some extent the students need to be able to understand these different structures. They need to be able to recognize that it’s appropriate to do certain types of actions and not so much in the others. Being able to work between different environments can equip the students to be able to succeed in multiple contexts, but also recognize the value of different types of participation in this example so that they can continue to grow as learners.

For Your Information

Students can be invited to help develop or define their classroom’s rules. The ability of the group to offer input can help build classroom community and encourage student ownership of the rules. It’s not unusual for students to come up with the very same rules that the teacher would have written, but they’ll have greater respect for them if they’re allowed a say in their formation.

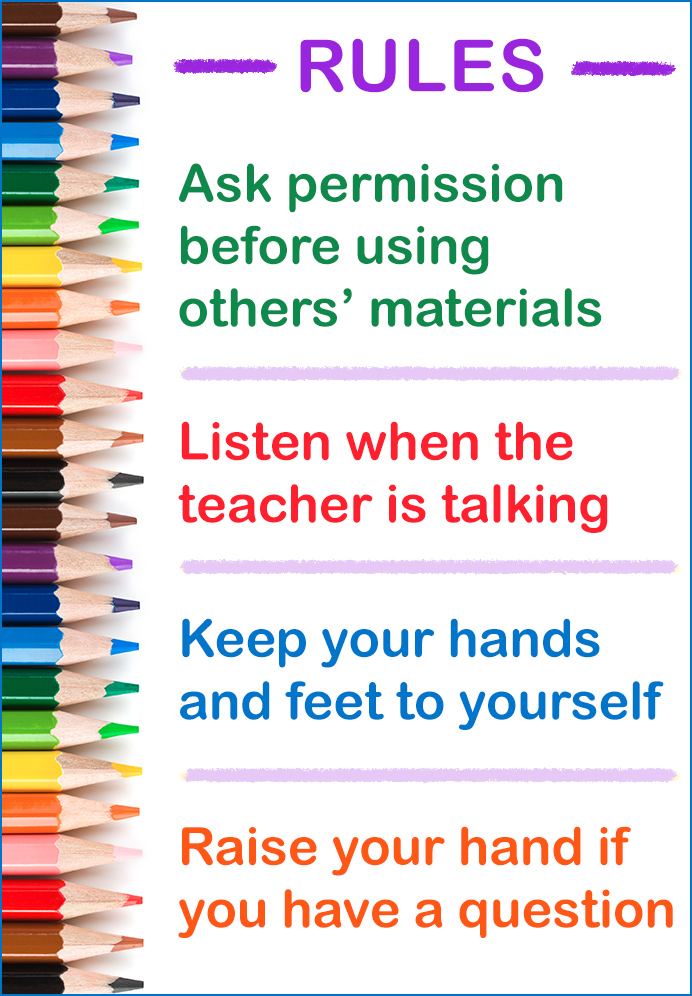

Just as every teacher and classroom is different, so, too, will classroom rules differ across teachers and grade levels. And because rules should be based on realistic, age-appropriate expectations, the way in which they are written and the need for visual cues may likewise vary.

Primary (e.g., grades K-2): These students benefit from brief statements and visual supports like photographs or illustrations.

Intermediate (e.g., grades 3-5): These students typically need only a list of written rules posted in the classroom.

As you compare the two sets of classroom rules below, one for a primary classroom and one for an intermediate classroom, notice how each set follows the guidelines while taking students’ ages into account. Also note the difference in the way the rules are written and the use of visual cues.

Mr. Nichols’ Rules (1st grade)

Ms. Amry’s Rules (3rd grade)

For Your Information

As the use of technology increases in the classroom and personal devices (e.g., cell phones) are used more often by younger students, teachers may need to consider rules for how and when these devices can be used. Again, when doing so, teachers must make certain they align with district and school-wide policies.

Teaching Rules

Developing rules is an important first step to help students understand what’s expected of them in the classroom. However, for students to learn the rules and follow them every day, teachers must intentionally and explicitly teach them. They can do this using the following four steps.

Step 1: Introduce — State the rule using simple, concrete, student-friendly language. For English learners, introduce the rules in the students’ home language when possible.

Step 2: Discuss — Talk about why the rules are important (e.g., “Why is it important to use walking feet?”).

Step 3: Model — Demonstrate what it looks like to follow the rule, using examples and non-examples. For example, for “Use walking feet,” demonstrate walking as an example and running and skipping as non-examples.

Step 4: Practice — Have students role play following the rule in different contexts (e.g., large group versus independent work).

Step 5: Review — Teaching the rules is not the end. Make sure you are reviewing them frequently. This is especially the case during the following situations:

- During large-group activities during which daily reminders about the rules can be especially important

- Prior to transitions when students often have difficulty remembering the rules (e.g., “Remember our lining up rule, ‘Quiet voices.’”)

- When one or more students are having difficulty following the rules (e.g., “I see running in the classroom. Remember, our rule is ‘Use walking feet.’”)

Tip

Rules should be displayed so that the teacher and students can easily view and refer to them throughout the day.

Listen as Lori Jackman describes how the posting of classroom rules allowed her to address behavioral issues more efficiently. Next, KaMalcris Cottrell explains how she gives her students the opportunity to help develop classroom rules. Finally, Ashley Lloyd explains how she teaches rules.

Lori Jackman, EdD

Anne Arundel County

Public Schools, retired

Professional Development Provider

(time: 0:45)

Transcript: Lori Jackman, EdD

When I was in the classroom, one of the things I would have posted on every wall was a list of the rules, positively stated. If I had someone who was doing an exceptional job at one of the rules, I could say, “Hey, so-and-so is doing a great job with rule number two. They’re following directions, and they’re on task,” and I could just touch and point to that poster to remind them of what they’re doing right. But also to use that “Hey, class, let’s take a look at rule number three. What are we supposed to be doing? That’s right. Get back on track.” And I could nonchalantly, as I walked around the room and as needed, point to it to remind them either what they’re doing, what I want them to continue to do, or what it is that they should start to do so that they can get back on track.

Transcript: KaMalcris Cottrell

I think it’s important to set rules early in your school year and maintain a consistent basis for these rules. I believe it creates an effective learning environment by setting expectations and structure for how the class will flow and proceed. I do have a few rules that are staples, but I give my students the opportunity to share what they would like to see happening in our classroom, ways that we can be respectful, responsible, and we list out things. And it allows students to have a conversation. If Johnny says, “Oh, I think we should chew gum in school. I don’t think that should be against the rules.” Sally might say, “Well, if we chew gum at school, what if it falls out of our mouth and gets stuck on a desk or stuck on shoes?” So it allows within the peer group a conversation of pros and cons. And I think it’s great because they both have valid points. So we talk about it as a class and we say, “Well, as a school, the rule is we cannot chew gum,” and it covers safety issues and cleaning issues. So we agree upon the no-gum-in-school, but I love the opportunities that pop up with the students giving their suggestions and students agreeing or not agreeing. And we do talk about it’s OK not to agree, but we’re going to do it respectfully, and if you have something you would like to say, we don’t have to agree with you. We will respect you, but we don’t have to agree with your statement, such as the gum incident. But it gives the students ownership for the classroom that they’re going to be in all year. So they’re setting these expectations. I hold them to those expectations. And, of course, I make sure that the foundational ones are in there, but they do a great job of covering most of them. And it gives an easier redirect to say, “Look, we agreed we’re going to do this. Are you doing this right now? Take a minute and think about it,” and I’ll leave it at that because they have the chance to see the rules that are in our room hanging on the wall for everyone to see. We write it nice and big as a reminder. It is an easier redirect, even it could be non-verbal, which is even better because then everything keeps flowing. There’s no interruption.

Transcript: Ashley Lloyd

Classroom rules are the key to maintaining an effective learning environment. When children know what is expected of them, introducing and teaching classroom rules is a multi-step process in my classroom. It always starts with explicitly teaching the rules through words and pictures and then we take some time to role play, and that includes examples and non-examples. So we make sure that everyone understands what is appropriate and what is inappropriate. Then we move on to the guided practice steps where children are guided through the rules and expectations and then rewarded for those small things, whether it be a high-five, whether it be some extra time outside because everyone figured out that rule. But it really is important to give them that guided practice. We make sure that we hit back on these things after every transition, every time we’ve been out on a break. Every Monday when we come back children need to be taught. So we make sure that we’re going through those things and that the expectations are visual and posted at all times so they can always be referred back to. I invest instructional time in teaching rules because it actually saves so much time throughout the year. If children know what’s expected of them and we can just get to work, we don’t have to take time to stop, reassess, and get back on track because everyone knows what is expected of them.

Research Shows

- When teachers create classroom rules that are stated positively and describe expected behavior, students engage in disruptive behavior less often.

(Alter & Haydon, 2017; Reinke et al., 2013) - When teachers develop clear rules and procedures, students feel more confident about their ability to succeed academically.

(Akey, 2006) - Rules are most effective when they are directly taught to students and when they are tied to positive and negative consequences.

(Alter & Haydon, 2017; Cooper & Scott, 2017)

Activity

![]() Now it’s your turn to create your own set of rules. You can develop rules for your classroom (current teachers) or for the grade level you hope to teach someday (future teachers).

Now it’s your turn to create your own set of rules. You can develop rules for your classroom (current teachers) or for the grade level you hope to teach someday (future teachers).

Page 5: Procedures

In addition to creating rules, effective teachers develop procedures—the steps required for the successful and appropriate completion of a number of daily routines and activities. Procedures are particularly important for routines and activities that are less structured and during which disruptive behavior is more likely to occur (e.g., morning arrival, dismissal).

In addition to creating rules, effective teachers develop procedures—the steps required for the successful and appropriate completion of a number of daily routines and activities. Procedures are particularly important for routines and activities that are less structured and during which disruptive behavior is more likely to occur (e.g., morning arrival, dismissal).

Developing Procedures

Rule number one: Keep it simple. Teachers should develop easy-to-follow procedures for only those routines and activities for which it is necessary. Excessive or cumbersome procedures can be confusing and counterproductive. To help determine whether a procedure is warranted, teachers can consider the questions in the table below.

| Why | is this procedure needed? |

| Where | is this procedure needed? |

| What | is the procedure? are the steps for successful completion of the procedure? |

| Who | needs to be taught this procedure? will teach this procedure? |

| When | is this procedure needed? will the procedure be taught? will the procedure be practiced? |

| How | will you recognize procedure compliance? |

Following are some common elementary routines or activities that might benefit from procedures. Click on the links below to view sample steps for each.

For Your Information

As you might expect, different teachers and grade levels will have different classroom procedures. Additionally, the way in which the procedures are written and the need for visual cues may vary. Regardless, these should be realistic and age-appropriate. Primary students benefit from brief statements and visual supports. Intermediate students typically need only a list of written procedures.

Morning arrival

Procedure:

- Greet teacher and classmates

- Hang up backpack and coat in your area

- Place homework folder in desk and book to read on desk

- Get breakfast and quietly read while eating

- When breakfast ends, gather trash to put in bin

Morning meeting

Procedure:

- Eyes are watching

- Ears are listening

- Hands in lap

- Legs are crossed

Dismissal

Procedure:

- Clean up area around your desk

- Grab coat and backpack

- Teacher will call on row (or group) that is packed up, silent, and ready to line up first

- Walkers and car riders exit through hallway A

- Bus riders exit through hallway B

Walking in the hallway

Procedure:

- Eyes forward

- Hands to self

- Voices silent

- Feet walking

Turning in Assignments

Procedure:

- Double check for name at the top

- Pass assignment forward

- Student at front of the row collects assignments and hands to teacher

Restroom use

Procedure:

- Raised hand with fingers crossed

- Wait for teacher to nod yes

- Take bathroom pass

- Walk to the restroom quickly and quietly

- Wash hands

- Return to class and begin working again quietly

Throwing away trash/recycling

Procedure:

- Make a pile on your desk

- Wait for the trash helper to come around

- Gently put your pile into the trash can

Asking for help

Procedure:

- Silently raise hand

- Wait patiently for teacher

- If teacher is busy, try working on the next question or problem

Getting/Returning Laptops

Procedure:

- Quietly stand and walk to the cart

- Gently unplug/plug in your laptop

- Hold it with two hands

- Walk back to your seat

Lining up

Procedure:

- Facing forward

- Silent mouths

- Hands to yourself

Going to lunch

Procedure:

- When called, get your packed lunch, and get in line

- Walk down the halls quietly, keeping feet and hands to self

- Enter cafeteria and if getting lunch get in line

- Once served, sit at your assigned table

- Remain seated until signaled to clean up

- Throw away trash on way to lining up by exit door

Sharpening Pencil

Procedure:

- Silently hold up one finger

- Wait for your teacher to nod yes

- Walk to the pencil sharpener and sharpen pencil

- Return silently to your desk

Fire and disaster drills

Procedure:

- Stop what you are doing

- Voices off, ears listening

- Quickly and quietly line up at the door

Tip

For best results, write each procedure in the form of a numeric list indicating the correct sequence of steps.

It’s important to remember that although certain procedures might work in some classrooms, they may need to be changed or modified in others. It’s completely normal (and recommended) to adapt a procedure to best meet your needs and the needs of your students.

Listen as Andrew Kwok discusses developing procedures that are culturally responsive or sustaining.

Andrew Kwok, PhD

Assistant Professor, Department of Teaching, Learning, and Culture

Texas A&M University

(time: 2:52)

Transcript: Andrew Kwok, PhD

The main goal for procedures is ways to expedite regular processes within the classroom and being able to maximize the time students have to learn and to engage. I think that requires student input not for all procedures, but for certain ones that are particularly difficult or challenging or may just benefit from having other perspectives in order to solidify some of these classroom procedures. The one that really stuck out to me is the idea of tardies or absences because it’s going to happen within the classroom and teachers need to really consider what that may mean for student learning. Oftentimes, teachers just outright penalize students for coming late to the classroom. But I think it’s different when you start considering the student and the root of that challenging action. Maybe their parents are working multiple jobs and getting them to school in time isn’t a possibility, or there’s just some lag in terms of the priority of being right on time. And so being able to work with that student and work with the family to share your view of punctuality but also being flexible and saying, “Well, I understand you just can’t come on time because you’re getting off of a night shift.” Is there a way to not penalize the student? Can we spend additional time after school? Can we spend time during lunch in order to make up for the missed learning or the curriculum that is occurring? I don’t think students should be penalized for things that are definitely out of their control. And so the more the teacher can work with them in order to solidify things and understand the background of what’s happening will allow for structures within the classroom to be more culturally responsive.

In general, being culturally responsive towards aspects of classroom management really comes down to understanding the root of these behaviors or potentially misbehaviors. To you, it may be a misbehavior, but the more that the teacher can dig in and understand why things are happening, that can allow for changes to happen within the classroom that are more responsive to those students. So part of it is an individual consideration, but it can be a cultural difference that is occurring that certain groups of students are acting a certain way. And so it’s up to the teacher to understand why, as opposed to forcing those students to learn or to engage in the way that only the teacher wants. And so the more that they can find out the why of things happening, the better they will be at being able to manage the classroom.

For Your Information

Throughout the school day there are many transitions, both big (moving from class to class) and small (ending math and starting science). Unplanned or unsuccessful transitions can lead to disruptive behaviors and lost instructional time. Much as when they develop procedures for routines and activities, teachers should provide clear, consistent steps for transitions. Below are some possible steps and examples to help successfully prepare students to transition to the next routine or activity.

transition

glossary

| Transition Steps | Example |

|

“I need all eyes on me in 5 – 4 – 3 – 2 – 1.” (Hand raised in air, counting down) |

|

“In one minute, we will go to lunch.” |

|

“When I say ‘start,’ I need everyone to close your notebooks, put everything in your desk, push in your chair, and line up at the door.” |

|

“Shelby, will you please repeat my directions?” |

|

“Start.” |

|

“Thank you to my students who were silent as they lined up. Unfortunately, a few students were talking. I also see that a few chairs are not pushed in. Please go back to your desks. Let’s try lining up again.” |

The Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) has developed a guide that recommends teachers use student specific transition signals (e.g., use of home language, call-and-response, song lyrics). This practice ensures that all students’ cultures, lives, and home languages are reflected in the classroom each day.

The Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS) has developed a guide that recommends teachers use student specific transition signals (e.g., use of home language, call-and-response, song lyrics). This practice ensures that all students’ cultures, lives, and home languages are reflected in the classroom each day.

PBIS Cultural Responsiveness Field Guide: Resources for Trainers and Coaches

Teaching Procedures

Keep in Mind

Procedures cannot be taught (and memorized by students) in one day or even one week. Because there are multiple steps required to successfully complete a procedure, learning them takes time and practice. Teachers should review procedures throughout the year, but especially when one or more students are having difficulty following them (e.g., “Remember, our procedure for turning in homework is to put it in the basket.”).

Although developing procedures that appropriately allow students to complete daily routines and activities is an important first step, teaching procedures is critical to the creation of a calm, consistent classroom environment that maximizes instruction and minimizes disruptive behaviors. Below is a list of recommended steps for explicitly teaching classroom procedures:

Step 1: Introduce — Outline the steps necessary to successfully complete a routine or activity.

Step 2: Discuss — Talk about why the procedures are important (e.g., to make sure everyone has the supplies they need at the beginning of a lesson).