How can educators recognize and intervene when student behavior is escalating?

Page 9: Recovery

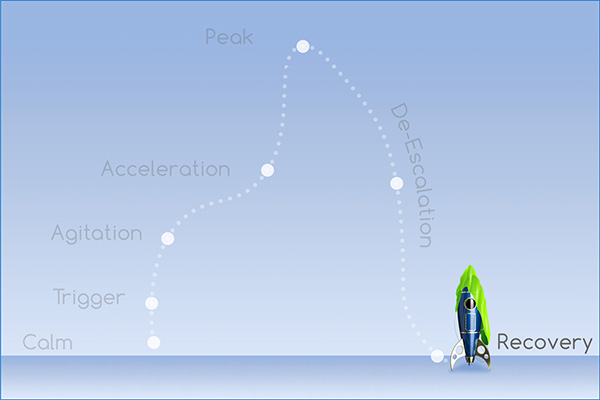

Once the teacher has restored calm to the classroom and the student’s behavior has appropriately de-escalated, the student enters the final phase of the acting-out cycle—the Recovery Phase. This phase marks a transition between the De-escalation Phase and the Calm Phase. The teacher should support the student as he gradually reintegrates into the classroom.

Once the teacher has restored calm to the classroom and the student’s behavior has appropriately de-escalated, the student enters the final phase of the acting-out cycle—the Recovery Phase. This phase marks a transition between the De-escalation Phase and the Calm Phase. The teacher should support the student as he gradually reintegrates into the classroom.

What a Student Looks Like

In this final phase, students are generally subdued. They may:

- Avoid talking about the incident

- Seem guarded

- Prefer working alone on a familiar task

Strategies To Implement

For the most part, strategies used in the initial Calm Phase are also applicable to the Recovery Phase. See the table below for some additional strategies and tips to support the student during the Recovery Phase. The way in which the teacher implements these strategies may vary depending on the nature and severity of the peak behavior.

| Strategy | Tips |

| Conduct a brief (3–5 minute) debriefing session with the student to review the debriefing form the student filled out in the De-escalation Phase. |

x

debriefing session A brief discussion between a student and an educator to review a significant behavioral event, prevent it from occurring again by strategizing different responses, and transition back to normal activities; typically utilized during the Recovery Phase of the acting-out cycle.

Click the form below to view a sample form that teachers can use when debriefing with a student. Note: Though debriefing may take away from instructional time, it is time well spent. Debriefing can help the student and teacher understand the behavior to prevent it from happening again. The absence of debriefing may signify to the student that he got away with the behavior. |

| Conduct a concise debriefing session with the class. |

In instances where the student is removed from the class:

|

| Reinforce the student’s positive behavior. |

|

| Gradually reintegrate the student into normal classroom routines. |

|

| Hold the student accountable for her behavior. |

|

In this video, Ms. Harris illustrates the steps that teachers should take during the Recovery Phase (time: 7:22).

Transcript: Recovery Phase

[bell rings]

[Students get up from their desks and begin leaving the classroom.]

Teacher: Hey, do you mind staying back for a second? Do you have your debriefing form?

Ava: Yes.

Teacher: Okay, good. [addresses the rest of the class] See y’all.

Teacher: Hey, I’d really appreciate if you would pick up your tablet for me please.

Ava: Okay. [picks up tablet from floor]

Teacher: Thank you. [pulls up a chair to sit with Ava] So how are you feeling now?

Ava: Fine.

Teacher: From your perspective, I’d like to hear about what happened today.

Ava: It’s just that we went from a fun review game to working on our projects. It was just too boring.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand that. Sometimes it’s hard to transition from fun stuff to, into independent work.

Ava: I was just too excited from the game.

Teacher: Yeah, I like to do fun stuff too, but we also have to do projects where we have to focus and do independent work. It’s to prepare you for what comes after high school. So next time, when you’re not quite ready to do independent work, what will you do?

Ava: Play a game on my phone.

Teacher: [laughs] No, seriously. What will you do when you’re not quite ready to work?

Ava: Maybe go get a drink of water to reset and take a break.

Teacher: Hey, that works for me. Um, but there is one more thing that we’ll need to talk about: the tablet. I’ll have to talk with your mom and an administrator about it first.

Ava: Okay. My mom’s going to be p****d.

Teacher: Hey, we can work through it. I just want to make sure that you’re okay and you’re back on track, back on track in this class. Okay?

Ava: I’m good now.

Teacher: Okay. Well, thank you for being able to stay after class and chat. Um, here’s your pass, and I already talked with Mr. Thouman, so he knows you’ll be coming in a little later. Okay?

[Ms. Harris hands Ava the pass.]

Ava: Thank you.

Teacher: Okay.

[ Johanna Staubitz commentary ]

Ms. Harris and Ava get to have a debriefing conversation now, now that Ava is in the Recovery Phase. So this happens later. It’s after class has ended. And notice that how even before the class left the room, Ms. Harris privately asks Ava to stay back. It’s really important that’s done privately. Again, the student’s privacy is going to make a big difference in whether behavior re-escalates or teacher and student are moving through Recovery together. So Ava agrees to stay back, and the first thing Ms. Harris has Ava do is restore the space, pick up the tablet. And that’s part of holding Ava accountable for her behavior is having her repair any damage that she’s done, even if it’s just kind of things being on the floor. And then she asks how Ava is feeling, “How are you feeling now?” and then what Ava’s perspective is on what happened. That’s really important to let the student reflect. Sometimes it’s a lot better to ask than to tell, and that can give Ms. Harris the opportunity to really build on Ava’s reflections rather than be the one supplying the information, in which case Ava is going to be a little less bought-in on the conversation. So when Ava shares that she was frustrated by the transition to the less interesting activity, Ms. Harris does really nice job expressing empathy. Again, this is really important. Let’s validate our students’ feelings when they choose to express them. That teaches them to express their feelings, which gives us more information and helps us learn about their triggers so that we can anticipate them next time and ideally prevent them or respond more quickly. And also it just builds trust between teacher and student. And also as a third thing helps to build social emotional skills and self-regulation awareness. Students have to be able to notice their feelings and know that they are valid. So that’s a really important part of this debriefing conversation.

Another important thing that Ms. Harris does that I really, really like is that she includes a rationale for why students have to do that less engaging work sometimes is what prepares us for life after high school. I think if Ms. Harris wanted to do that even better, she would question Ava a little bit about Ava’s values and goals and connect engagement with that independent work to Ava’s values and goals. And that’s a really great way to, in the short term, increase motivation and buy-in on something so that’s very important and it facilitates some language skills as well. So after that, Ms. Harris says, “Well what can we do next time?” And Ava sort of makes a joke. You almost can’t tell she’s joking because she’s playing it really straight, and that’s because she’s still a little down about what happened and probably feeling a little weird, even though she’s feeling better than she had been immediately after the peak when she ran out of the room. But she said, “I could play a game on my phone” and Mrs. Harris jokes back like, “No but seriously,” which again is a good sign they already have a relationship built which is going to facilitate conversations like this. When pressed, Ava suggests, “I could go get a drink of water to reset.” And they agree on that, and I think they probably could have brainstormed some additional solutions as well. So just know you don’t have to leave with just one. And then there are two things left. One is the accountability. So at this point, Ms. Harris says, “All right, there’s one other thing, you know, the tablet. I’m going to have to call your mom about that.” And that’s because Ava threw an expensive piece of school property and you know again, she acknowledges that Ava is a little worried about this. Ava says, “My mom’s going to be mad.” And I would also add that in most schools there are rules about cursing. So if assuming that Ava’s yelling curse words at Ms. Harris prior to running out of the classroom is something that’s a problem and it is in most places, that’s also worth talking about and giving Ava heads up that that’s going to be addressed. Same with running out of the classroom. I mean all of these things might have specific consequences tied to them, and this is the time to communicate that to the student during Recovery. Now, this debriefing conversation in the Recovery Phase closes with Ms. Harris making a supportive statement and thanking Ava for staying afterward to chat. It can be hard to do this as the teacher, especially if you just had a student in the last hour scream curse words at you, tell you your class is stupid, and run out of your classroom. But it’s really important to really reestablish and make it clear to the student where they stand with you and that you care about them, even if that is hard to do. We kind of we are kids aren’t responsible for our feelings, we are, but we are responsible for teaching them how to engage in these conflict resolution conversations. So she’s supportive, thanks Ava for staying. That’s going to make Ava more likely to have a conversation like this in the future and helps develop her self-regulation skills. So very nice, Ms. Harris.

If strategies used in this phase are successful, the student will return to the Calm Phase. First, Kathleen Lane explains more about how a teacher might debrief a student and the class during the Recovery Phase. Next, Pamela Glenn explains her process for the Recovery Phase. Finally, Dr. Gloria Campbell-Whatley discusses the importance of using restorative practices to support students during this phase.

Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Professor

Department of Special Education

Associate Vice Chancellor for Research

University of Kansas

(time: 3:46)

Gloria Campbell-Whatley, EdD

Professor, Special Education

University of North Carolina, Charlotte

(time: 1:41)

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

During the recovery phase, generally, schools will have a debriefing form that allows them an opportunity to have a structure to walk through this problem-solving process with the student, to take a quick look at what just happened, what could be done differently so that it can be prevented next time. And we can think about this as a debriefing activity. Now, hopefully, when you’re sitting down to do this debrief with the student during this time, you’ve been successful in giving them an independent activity that they can do, and the rest of the class is back on track because we do not want all eyes on the student. At this time, the teacher can go back to the student and say, “I know that was really uncomfortable and I’m feeling uncomfortable too with what just happened. But we’re at a time now where we need to talk through it so we can do things better the next time.” If you don’t know what that trigger was, you might say something like, “It seemed to me I didn’t even feel like I saw this coming. I just looked over and I saw you doing this. Can you tell me what happened before that?” And basically what you’re doing in this moment is talking with the student to figure out why did this happen? What set the stage for this to even take place? And the goal is not to blame anybody, but the goal is to learn from it so that we can prevent this from happening again in the future. And it might be something as simple as “When you gave that last answer in class and you said I was wrong, it totally embarrassed me in front of all my friends and I just didn’t feel like doing anything like that. And the more I thought about it, the more frustrated I got because I really felt like you called me out in front of my friends.”

And it may be that the teacher totally missed that and didn’t even realize saying “No that’s not quite right” was offensive to that student or was humiliating in some way. So with that new information together, that teacher and that student can come up with an action plan. And it literally could be as simple as maybe the student needs a little more time to think about questions so that they can have a chance to come up with the right answer ahead of time.

So you might come up with something like, “Tomorrow when you come back to this period, I’m going to ask you a question in our discussion section, and I want you to think about this. And if you want to bounce your ideas off some of your friends or check with me before class starts, I’m happy to do that.” Or you might even say, over the course of a normal conversation, “Hey, Jesse, I’m going to want to get your opinion on something in just a second, but I’m going to go ahead over here and check in with Alexis to get her thoughts first.” And that little interaction gives Jesse an opportunity to think for a couple of seconds. “All right, she’s going to ask me a question and I know this is going to be okay.” Do some positive self-talk. For some students, it’s just really, really hard [laughs] to get corrective feedback or be told that they did something wrong or said something wrong, and it feels much more personal than it was intended to come across. So for those students, you might come over and say, “Hey, I know you’re finishing up that first draft of your college essay right now, and I’m going to come back in just a couple minutes and we’re going to edit your first draft. We’re just going to be looking at it for some basic grammar things. So when you get a chance, just take a quick look over it and double-check your work. And I’ll be back in just a minute.”

So that lets them know I’m about to give you some feedback and then it gives them a chance to double-check themselves so that they can be ready to hear what you have to say. So essentially, this debriefing session gives us a chance to learn about what went wrong from both people’s perspective and come up with a new approach for moving forward the next time. It is not to blame. It is to learn.

Transcript: Pamela Glenn

While that student is having a minute, I’ll go back to the other students. “Is everybody okay? Are there any questions? Do you have a partner that you can work with? Because I have to go take care of this right now. I am so sorry that this is happening and blah, blah, blah. You’re doing a great job. I love how you’re being there for your family member that needs a little extra time.” So they’ll get to work. And then I’ll go back then, and Johnny and I will have a very quick “Are you okay? What do you need? You know, we got to fix this.” Sometimes you can fix it in the moment. Other times you have to come up with a longer plan because you still have a class of students that are working. So, if it’s something that we can just quickly patch up, “Are you good to come back and keep going?” Depending on whatever’s got them agitated, if they can re-convene with the community, we do. If not, then they sit with me. If not, and they need to move out of the room, then I’m going to call for a guidance counselor or somebody. I don’t like for a student to get to that state and then leave and debrief with somebody else because then they have to explain it, and maybe the person doesn’t know them. So, I like to do that myself, but if they just need a time out of the room, then I’ll give them that option. And then we’ll get together. Then we’re going to talk about this. That’s a real one-on-one conversation. For me, the recovery process is… I don’t want to do this lots and lots of times. The first time we do it, it’s going to be deep and meaningful. Is it likely going to happen again? What can we put in place that this does not happen again? And I’m big on writing down a plan. We have something we called a behavior reflection. I’m going to ask you, when you’ve calmed down, “Are you able to speak about this now? What exactly was happening?” My voice is soft. It’s low. I’m listening. I’m doing a lot of reflecting. “I hear you say that the work was hard, and you didn’t understand. I hear you saying…” So, there’s a lot of that happening. Own what you did. We talk about that a lot. You mess it up, you dress it up. You own it. You messed up. So, “What did you do that was wrong?” And you’ll hear them say, “I should have never thrown my chair. They’ll be very remorseful. I’ve had very few students that have gotten to that phase, and they’ve looked and said, “Yeah, I did that. Now what?” I’ve [laughs] never really heard that. It’s been a “I shouldn’t have done that.” What could have happened or what did happen? “I threw the chair and it hit my friends and I didn’t mean that.” “Okay, so now what are the repercussions of that?” “My friend was hurt.” “Now, what have you got to do?” “I’ve got to make that right.” “How are you going to make that right?” We’ll then write down a plan of this is what the behavior was, and this is what I did. So, the next time I feel like this, I’m going to… And then we’ll put 3 to 5 points. And then I have a little column of what am I going to do to help you make sure that this happens. I’ll send it home, a copy, the parent will sign to say, “I understand that this has happened. At home, I’m going to reinforce it.” It’s something between the student, the parent, and me. Nobody else sees it.

Transcript: Gloria Campbell-Whatley, EdD

Now in the Recovery Phase, restorative discipline or restorative justice is very important. Restorative justice or restorative discipline is a way that you can fix whatever wrong that you have done. So you get a chance to look at your behavior, view the behavior, and then correct it. And then you begin to talk about, okay, this is something that you did. It wasn’t right. Now, let’s correct it. What can I do to correct it? And that’s very different from “I’m suspending you, get out of the door, go to in-class suspension.” There is no restoration. And that restoration is important to the student to fix that offense. So you fought in the cafeteria and you slung some food over here, so you go in the cafeteria and you do some duty, you wipe down tables, you sweep or clean it up. You’re still there, you’re not suspended, it leaves you still as part of the class. You’re not thrown out. You are going to fix what you did. And then you begin to handle things in a different way when you are about to commit an offense. You’ll handle it in another way because you fixed it. So you know that there’s another way to handle it. It really works well in that Recovery Phase.

Let students start with a clean slate after the Recovery Phase. Although it can be difficult to move forward, providing the student with the opportunity to start fresh can motivate him to engage in more appropriate behaviors.

Completing the Recovery Phase can be difficult. The teacher must deal not only with the misbehaving student but also with the emotions and expectations of the class. In addition, the teacher must deal honestly with her own mistakes and feelings surrounding the incident. The goal must always be to create a healthier learning environment.

Activity

In the video below, Ms. Harris conducts a debriefing session with Sam.

Transcript: Recovery Phase

Teacher: Let’s talk about what happened. The text was hard, and I noticed you got frustrated when you were reading. What happened there?

Sam: I didn’t know where to start. You kept calling me out to get started, but it’s just it’s hard to focus when I couldn’t remember all the things I needed to be doing. And when you wanted me to talk in the hallway, everyone started laughing and I got really frustrated.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand. And I’m sorry about calling you out in front of everyone. I can definitely work on that for next time. So what do you think you can do differently?

Sam: I don’t know. Ask for help.

Teacher: Yeah, that’s a great start. So what can I do differently to help you?

Sam: You could, I don’t know, write the things we need to do on the board.

Teacher: Yes, I can definitely do that in the future. So do you have anything else you want to talk about?

Sam: Yeah. It’s just, it’s kind of embarrassing when I feel like I need to ask for help when other students don’t.

Teacher: Yeah, I get it. Other students need help sometimes too. It’s just how we learn. Everyone’s different.

Sam: Oh, okay.

Teacher: Yeah. And I bet it will also help other students if you ask a question next time.

Sam: Yeah, I know. I’ll give it a shot.

Teacher: Yeah, that works for me. Thank you for staying after class today. How are you feeling now?

Sam: Pretty good. Sorry I ripped up the text. Uhh, I can tape it back together and still use it tomorrow.

Teacher: [laughs] Thanks, Sam, but I already have another copy that you can use. So go on ahead and get out of here and I’ll let Ms. Gaines know that you’ll be coming a little later. Okay?

Sam: Okay.

Teacher: All right.

[Sam gets up to leave.]

After reviewing the video, answer the following questions. You may type your answers in the field below the video. However, this field is provided for reflection purposes only; your answers will not be available for download or printing.

- Do you think this debriefing session was effective? Is there anything else Ms. Harris should have included in the debriefing session? Explain.

- Do you think Ms. Harris should have debriefed with the whole class? If so, how could she have conducted this debriefing session? If not, why?

- Moving forward, how can Ms. Harris use the information gleaned from the debriefing session to prevent Sam’s behavior from escalating when he encounters a trigger?

Now that you’ve had a chance to reflect, listen to Johanna Staubitz’s feedback.

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Associate Professor, Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

Debriefing session overview

(time: 2:53)

Addressing future triggers

(time: 1:51)

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Debriefing session overview

Some signs that a debrief conversation is effective is the engagement of the student during that conversation and the way the conversation ends. So throughout this conversation, Sam was forthcoming and he volunteered some solutions, like “I could ask for help.” He also volunteered more about his situation and his perspective. “It’s really hard for me to know that I’m the only one who needs help.” And Ms. Harris validated all of these things and also explained “You’re not the only [laughs] one who needs help. Often if you have a question, other people do too.” She went so far as to apologize for calling him out in front of everyone because he said that was something that was hard for him, and asked what she could do differently after Sam said what he could do differently. So they’re having this really collaborative conversation in which they’ve covered what happened, what’s Sam’s take on it, and also what can we do differently in the future to help things go more smoothly. Other signs that this conversation was effective was Sam’s offer to fix the book at the end. That just showed they’re on good terms at the end of this conversation. Ms. Harris demonstrates that repaired relationship too when she says, “Go on and get out of here.” That’s a very familiar way to communicate with a student. It shows they’ve become more comfortable again. And she, of course, takes care of the logistics of getting Sam to his class even though he’s going to be late.

One thing that Ms. Harris didn’t do was address the consequences for Sam’s behavior. Maybe they’re going to do that later. But that really is something that needs to happen in a debriefing conversation. Ostensibly there are school policies or consequences assigned to profanity and property destruction, and the debrief conversation is where those things should be communicated so Sam knows what’s going to happen next and is held accountable. And all that can still be done with empathy.

So another question is, should Ms. Harris have debriefed the whole class? It comes down to the comfort level of the teacher and the students in the classroom and the access the teacher has to those students without Sam present. I don’t necessarily think debriefing the whole class would be necessary in this situation for them. I think, based on their facial expressions, they were probably pretty uncomfortable. But there wasn’t a direct threat to their safety and none of Sam’s behavior was directed toward peers. So it might be okay to just make sure students know that they can come to Ms. Harris with questions or concerns. And I’ll just say one more thing about this [laughs] and it is something about how we can use preventive methods to set the stage for debriefing or to kind of circumvent the need for it sometimes because it is hard logistically to find time with students to do that, especially without the target student present. And that’s simply to talk in advance about how there will be difficult situations and how everybody needs support in different ways at different times, how classmates can support one another, and how if you’re a concerned bystander, you can follow up. That way there are procedures in place and everybody’s crystal clear on how to get their needs met after a crisis.

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Addressing future triggers

Moving forward, how can Ms. Harris use this information that she’s gotten from Sam in the debrief conversation to prevent his behavior from escalating when he encounters a trigger? And one really easy thing she can do is use precorrects. When she’s giving instructions for independent work, it’s a good idea to remind all students that if they miss something, they should ask for help. Ms. Harris needs to make sure to reinforce those requests for help by providing it in appropriate ways that are sensitive to the situation. Student asks for help publicly, provide help publicly. Student asks for help privately, come on over and don’t talk across the room, just to help protect their dignity. Also, Ms. Harris can make sure to give really clear instructions. She did state her instructions clearly, but she stated them once and moved on. A good thing to do, just as a classroom management tactic, is to always check for understanding after delivering instructions. And there are a lot of different ways that can be done. One way is to simply say, “All right, who can tell me the first thing we need to do?” And calling a volunteer to say what the first step of the instruction was. “Who can tell me the second thing to do?” And so on and so forth. Finally, regarding the clarity of instructions, it’s going to be helpful not only to students like Sam, but the other students of Ms. Harris’, if the instructions are accessible throughout the work period. So it’s not a one-time statement. If you snooze, you lose. Write them down on the board, just like Sam suggested in the debrief conversation. Project them on a slide if you’re using a PowerPoint slide deck, and just make sure students have access to them because even if they heard them the first time, maybe they get into the assignment and forget what the next step is. That is good for everyone and certainly going to be good for Sam. And of course, Ms. Harris, now that she knows more about Sam and his triggers, will be more vigilant and looking out for signs so that then she can swoop in and intervene quietly to support him.