How can educators recognize and intervene when student behavior is escalating?

Page 2: Acting-Out Cycle

When they are confronted by challenging behaviors such as yelling, swearing, or fighting, teachers often remark that “This behavior just came out of nowhere!” And though this might seem to be the case, there are typically warning signs that preceded the behavior. To be fair, these signs can be easily overlooked in a busy classroom full of students. However, as teachers learn more about each student, they can become aware of things that are likely to trigger a student’s challenging behavior. In fact, most students who consistently exhibit these types of behaviors typically progress through a seven-phase process known as the acting-out cycle, as described in the table below.

When they are confronted by challenging behaviors such as yelling, swearing, or fighting, teachers often remark that “This behavior just came out of nowhere!” And though this might seem to be the case, there are typically warning signs that preceded the behavior. To be fair, these signs can be easily overlooked in a busy classroom full of students. However, as teachers learn more about each student, they can become aware of things that are likely to trigger a student’s challenging behavior. In fact, most students who consistently exhibit these types of behaviors typically progress through a seven-phase process known as the acting-out cycle, as described in the table below.

| Acting-Out Cycle | |

| Phase | Description |

| Calm Phase | Student behavior is characterized as goal-directed, compliant, cooperative, and academically engaged. The student is responsive to teacher praise and willing to cooperate with peers. |

| Trigger Phase | Student misbehavior occurs in response to an event either within or beyond the school day. When a student encounters a trigger, he may become restless, frustrated, or anxious. |

| Agitation Phase | The student can engage in a variety of off-task behaviors. Some students might dart their eyes, tap their fingers, or start and stop their activities. Others might disengage or stare off into space. |

| Acceleration Phase | The student’s challenging behavior intensifies and is often directed at the teacher. It’s at this stage that a teacher often first recognizes that a problem is occurring. |

| Peak Phase | The student’s behavior is clearly out of control (e.g., yelling at the teacher, hitting others, destroying property) and may create an unsafe classroom environment. |

| De-escalation Phase | The student is less agitated and may be confused or disoriented. Many students will withdraw, deny responsibility, attempt to blame others, or try to reconcile with those they harmed. |

| Recovery Phase | The student is generally subdued and may wish to avoid talking about the Peak incident. The student returns to the Calm Phase. |

Click on the video below to learn about the seven phases of the acting-out cycle (time: 2:25).

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

In general, we encourage all faculty and staff to learn about the acting-out cycle. You can think of this as a seven-step cycle that begins with a calm stage. And although [laughs] not every student comes to school calm every day, we think at some point in their life they have experienced some type of calm. And then something sets that student off and that can be thought of as a trigger. And sometimes those are school-based things like assemblies or schedule change, or could it be a difficult assignment or something like that. And some of those triggers can also be non-school based. It could be coming to school tired or hungry, or having not slept well the night before, or having had an argument with their parents or a conflict with a peer. And then if those triggers aren’t noticed and responded to, then that behavior can shift from signs of agitation and then really ramp up to signs of acceleration. And it’s during that acceleration phase, the behavior can really ramp up. And that’s when it’s easy for teachers to begin to notice these concerns when those behaviors are escalating. And for some students, this acceleration phase can last for several minutes, and then left unchecked, it can continue to escalate if it’s not nipped in the bud right there. And eventually it creates these peak behaviors when behavior is very, very out of control. And that’s when we start to see things like verbal and physical aggression in the classroom in a way that sometimes results in property destruction or harm to others. And then following that, there is a de-escalation and then eventually a recovery phase. So, you’re going up and then you’re coming back down. The good news is that it is possible to interrupt this acting-out cycle much earlier in the chain, long before the student reaches peak behavior, which can be frightening for teachers and students alike, and not just the student experiencing the challenging behavior, but others in the classroom.

In addition, we’ve learned that timing is everything. Meaning that it’s important for adults to understand when low intensity support, such as reminding students of expected behaviors or providing praise when the student meets desired behaviors and even offering choices can be introduced efficiently and effectively, and also knowing when they should not be used. Because used at the wrong time, it could actually have a counterproductive outcome for the student.

Credit

The acting-out cycle diagram is adapted from Colvin, G. (2004). Managing the cycle of acting-out behavior of the classroom. Eugene, OR: Behavior Associates.

Recall from the Challenge that Ms. Harris has two students who exhibit challenging behaviors—Ava and Sam. The first video takes a closer look at what Ava’s behavior looks like within the context of the acting-out cycle (time: 5:37).

Transcript: Acting Out Cycle – Ava

[Calm Phase]

Teacher: All right, everyone. It’s a close race right now. This last question will determine who our winner is. Who led the Nashville sit-in movement?

[Students write their answers on their whiteboards.]

Teacher: Okay, let’s see those answers in three, two, one. Lift up your boards!

[Students lift up their whiteboards.]

Teacher: Great job! The answer was Diane Nash and John Lewis. Alrighty. Looks like… drum roll, please… [Students tap their desks to create a drumroll sound] Ava comes in first place today!

Ava: Oh yeah! Let’s go!

Teacher: With Jeshua coming in second and Sterling coming in third!

[Trigger Phase]

Teacher: All right, everyone, awesome job on that review. You can go ahead and move your whiteboard and your marker to the corner of your table. For the rest of the class, we’ll continue researching the historical figure you all chose for your project. You can go ahead and open your notes and get your tablets and get started on your project. As you all are working, I’ll be walking around the classroom, so if you have a question, just raise your hand for me.

[Ava raises her hand.]

Teacher: Yes, Ava.

Ava: You didn’t assign me a person.

Teacher: That’s because you were supposed to choose a historical figure that we discussed yesterday. So go ahead and open your notes and choose a person so you can get started on your project.

[Ms. Harris circulates around student desks.]

Teacher: Thanks, everyone, for getting started.

[Ava distracts a peer by showing him her tablet. They laugh.]

[Agitation Phase]

Teacher: Ava, again, please start working on your project.

Ava: What? You didn’t say I couldn’t use this site.

Teacher: I said you should be researching the historical figure that you chose.

Ava: I am researching. Look. [turns tablet so that Ms. Harris can see it]

[Ms. Harris gives Ava a stern look and walks away.]

[Acceleration Phase]

Teacher: Please close out of that site and begin working on your project.

Ava: I was looking at videos to research for your stupid class.

[Ava drops the tablet onto her desk.]

Teacher: Hey, we need to have a chat. [Motions for Ava to follow her.]

Class: Ooooohhhh!

[Peak Phase]

Ava: Shut up! I don’t need a f*****g chat! I hate your class!

Teacher: Hey, I need you to calm down! Don’t speak to me like that.

Ava: F**k you!

[Ava storms out of the classroom and knocks over a basket.]

Teacher: I need to take care of this. You all continue working on your own project. [picks up phone] Hey, Ava Jones just left my classroom. She’s headed down Hallway B, and it looks like she’s headed out to the parking lot.

[Some Time Later]

[De-escalation Phase]

Teacher: Class, continue working while I speak with Dr. Wheby.

[Ms. Harris opens the door for Dr. Wheby and Ava to enter the classroom.]

Teacher: Hey.

Dr. Wheby: Ava and I just took a walk to cool down. She’s filled out her debriefing form. I think she’s ready to get back to go to work. I also talked to Dr. Thouman. He knows that she’s going to be late for his class. So you’ll have time to talk with her after this class.

Teacher: Okay, great.

Dr. Wheby: Do you have something you want to say?

Ava: I’m sorry for how I acted.

Teacher: Hey, I appreciate that. We can talk later about what happened. Go ahead and just grab a new tablet and have a seat. And if you have any questions, just raise your hand for me. Okay?

Ava: Okay.

Teacher: All right. Thank you.

Dr. Wheby: Thank you.

[Ava sits down at her desk with a new tablet.]

[Recovery Phase]

[bell rings]

[Students get up from their desks and begin leaving the classroom.]

Teacher: Hey, do you mind staying back for a second? Do you have your debriefing form?

Ava: Yes.

Teacher: Okay, good. [addresses the rest of the class] See y’all.

Teacher: Hey, I’d really appreciate if you would pick up your tablet for me please.

Ava: Okay. [picks up tablet from floor]

Teacher: Thank you. [pulls up a chair to sit with Ava] So how are you feeling now?

Ava: Fine.

Teacher: From your perspective, I’d like to hear about what happened today.

Ava: It’s just that we went from a fun review game to working on our projects. It was just too boring.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand that. Sometimes it’s hard to transition from fun stuff to, into independent work.

Ava: I was just too excited from the game.

Teacher: Yeah, I like to do fun stuff too, but we also have to do projects where we have to focus and do independent work. It’s to prepare you for what comes after high school. So next time, when you’re not quite ready to do independent work, what will you do?

Ava: Play a game on my phone.

Teacher: [laughs] No, seriously. What will you do when you’re not quite ready to work?

Ava: Maybe go get a drink of water to reset and take a break.

Teacher: Hey, that works for me. Um, but there is one more thing that we’ll need to talk about: the tablet. I’ll have to talk with your mom and an administrator about it first.

Ava: Okay. My mom’s going to be p****d.

Teacher: Hey, we can work through it. I just want to make sure that you’re okay and you’re back on track, back on track in this class. Okay?

Ava: I’m good now.

Teacher: Okay. Well, thank you for being able to stay after class and chat. Um, here’s your pass, and I already talked with Mr. Thouman, so he knows you’ll be coming in a little later. Okay?

[Ms. Harris hands Ava the pass.]

Ava: Thank you.

Teacher: Okay.

(Close this panel)

The second video illustrates Sam’s behavior during the acting-out cycle (time: 6:48).

Transcript: Acting Out Cycle – Sam

[Calm Phase]

Teacher: Okay, today we’re going to read an informational text. Before we read the text, I want you all to make predictions about the central idea. Take about 30 seconds and then turn and talk with your partner about your predictions.

[Students talk to their partners sitting next to them.]

Sam: Umm, something about water…

Teacher: Great predictions, guys.

Sam: I’m not sure what exactly.

[Ms. Harris circulates around student desks.]

Teacher: I’m hearing a lot of good predictions.

Sam: Yeah, yeah. That makes sense.

Teacher: Alrighty! Let’s bring it back to the front in five, four, three, two, one. Let’s hear some predictions.

[Weston raises his hand.]

Teacher: Yes, Weston.

Weston: Uhh it seems like there’s a water shortage. The author might be trying to warn us about the possibility of not having enough water to drink or use in certain parts of the country soon.

Teacher: Nice! Great! Did anyone else make the same prediction?

[Students raise their hands.]

Teacher: Great! So today we’re going to be talking about water shortages across the world.

[Trigger Phase]

Teacher: I’ll give you all some time to read through the text by yourself. While you’re reading, I want you to go ahead and take some notes and evaluate the author’s argument using textual evidence. Also, when you’re finished reading, I want you to go ahead and write up a discussion question for me. Okay?

[Sam sighs heavily.]

[Agitation Phase]

[Sam stares into space.]

Teacher: Hey, Sam, are you reading the text? You seem a little distracted.

Sam: Yeah, I’m working on it.

[Sam puts his head down.]

Teacher: Sam, I need to see your eyes on the text.

[Acceleration Phase]

[Sam rubs his eyes and refuses to work.]

[Peak Phase]

Teacher: Sam, can you come chat with me in the hallway for a second?

Sam: No, I’m not going to chat. I’m not doing this f*****g assignment!

[Sam slaps his desk.]

Teacher: Sam, what’s going on with you today? Come out into the hallway.

[Sam rips his text and throws it onto the floor.]

Teacher: Okay, everyone, please continue working. We have about ten more minutes of independent work, and I’m seeing a lot of great note taking going on so far.

[De-escalation Phase]

[Ms. Harris circulates around student desks.]

Teacher: Great job. Great.

[Ms. Harris places post-it note on Sam’s paper that reads, “Hey, I know you’re upset. Take a minute. Is there anything I can do to help?”]

Teacher: Sam, are you feeling okay?

Sam: Yeah. I was just really frustrated.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand. This stuff is hard, and I’m trying to push you because I know how smart you are. Can you go ahead and pick up your text off the floor and fill out this form for me while everyone is finishing up their reading. [Ms. Harris places debriefing form on Sam’s desk.] And then we can talk later about what happened.

Sam: Yeah, okay.

Teacher: Thank you.

[Sam picks his text up off the floor.]

Teacher: Okay, everyone, the bell is about to ring. Make sure you have everything packed up.

[bell rings]

[All the students leave the classroom while Sam remains sitting at his desk.]

Teacher: See y’all. See you later. Bye.

[Recovery Phase]

Teacher: Let’s talk about what happened. The text was hard, and I noticed you got frustrated when you were reading. What happened there?

Sam: I didn’t know where to start. You kept calling me out to get started, but it’s just it’s hard to focus when I couldn’t remember all the things I needed to be doing. And when you wanted me to talk in the hallway, everyone started laughing and I got really frustrated.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand. And I’m sorry about calling you out in front of everyone. I can definitely work on that for next time. So what do you think you can do differently?

Sam: I don’t know. Ask for help.

Teacher: Yeah, that’s a great start. So what can I do differently to help you?

Sam: You could, I don’t know, write the things we need to do on the board.

Teacher: Yes, I can definitely do that in the future. So do you have anything else you want to talk about?

Sam: Yeah. It’s just, it’s kind of embarrassing when I feel like I need to ask for help when other students don’t.

Teacher: Yeah, I get it. Other students need help sometimes too. It’s just how we learn. Everyone’s different.

Sam: Oh, okay.

Teacher: Yeah. And I bet it will also help other students if you ask a question next time.

Sam: Yeah, I know. I’ll give it a shot.

Teacher: Yeah, that works for me. Thank you for staying after class today. How are you feeling now?

Sam: Pretty good. Sorry I ripped up the text. Uhh, I can tape it back together and still use it tomorrow.

Teacher: [laughs] Thanks, Sam, but I already have another copy that you can use. So go on ahead and get out of here and I’ll let Ms. Gaines know that you’ll be coming a little later. Okay?

Sam: Okay.

Teacher: All right.

[Sam gets up to leave.]

(Close this panel)

In this interview, Kathleen Lane offers more information on each phase of the acting-out cycle (time: 1:55).

Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Professor, Department of Special Education

Associate Vice Chancellor for Research

University of Kansas

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

The acting-out cycle is a really wonderful theoretical illustration about how problem behaviors occur. A lot of times teachers will say, “The student just started screaming out of control” or “The student just blatantly refused to do their work” or “just stormed out of the room for no apparent reason.” And what they’ve shown through this acting-out cycle is that behavior actually does occur in a chain. And what most teachers are noticing are either peak behaviors where students are completely out of control, either throwing a chair or using profanity, or being very verbally or physically aggressive. Or sometimes there are actually earlier behaviors that could have been detected before that big acting-out behavior occurred. We can think of this as a precursor behavior. It’s basically important for every educator, those in the general education and special education communities, to be empowered with the knowledge that we can look for these signs of behavioral challenges that show up much earlier in the acting-out cycle, such as being off task, and respond to those smaller challenges before those little things become really big behaviors that can feel pronounced and out of control. And frankly, they’re difficult to manage. Ideally, every teacher could learn about respectful, effective ways to respond to challenging behaviors. That generally begins with showing empathy towards that student that is beginning to show some challenging behaviors. At the same time, they’re maintaining the flow of instruction to keep other students engaged. And then they acknowledge students who are meeting those expectations and provide very clear, kind redirects to teach those students that are struggling the expected behaviors for that moment, and then allowing those students who are struggling time and space to get back on track. And as soon as they do, then reinforcing them as soon as they engage in those expected behaviors.

To understand and prevent challenging behavior early in the acting-out cycle, teachers must first understand that every behavior is an attempt at communicating something. In many cases, challenging behaviors are an inappropriate way for a student to either:

- Obtain something desired (e.g., attention, a tangible item, an activity)

- Avoid something not preferred (e.g., a difficult task, an activity, an interaction with a teacher or peer, an undesirable situation)

By understanding what a student’s behavior is communicating, a teacher can take steps to prevent or address the behavior before it escalates. Intervening early in the acting-out cycle allows the teacher to address the behavior while it is less serious and when students are more likely to respond to efforts at intervention. If teachers can prevent challenging behaviors from gaining momentum, they can stop more serious behaviors from occurring, and in turn support that student and maintain a positive, productive classroom environment.

Tiered Systems

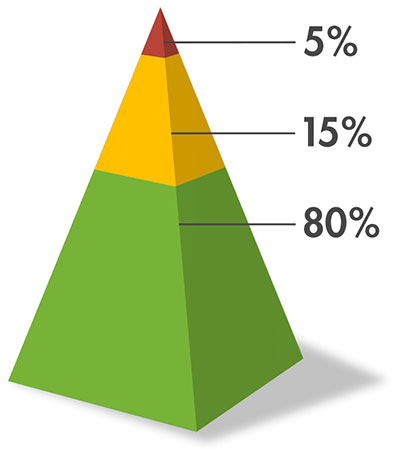

Many schools across the country are embracing a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) to prevent and respond to challenging behaviors. One such approach is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS). This framework provides the structure (broad practices and core principles) around which school-wide expectations are established, taught, and practiced. Within this tiered systems approach, educators identify and use evidence-based practices (EBPs) to improve academic and behavioral outcomes for all students. PBIS consists of three tiers of prevention—Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3—through which educators can provide a continuum of supports and services to promote appropriate behaviors and address challenging ones.

Many schools across the country are embracing a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) to prevent and respond to challenging behaviors. One such approach is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS). This framework provides the structure (broad practices and core principles) around which school-wide expectations are established, taught, and practiced. Within this tiered systems approach, educators identify and use evidence-based practices (EBPs) to improve academic and behavioral outcomes for all students. PBIS consists of three tiers of prevention—Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3—through which educators can provide a continuum of supports and services to promote appropriate behaviors and address challenging ones.

multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS)

A preventive framework that integrates high-quality instruction, assessment (i.e., universal screening, progress monitoring), increasingly intensive and individualized levels of instructional or behavioral intervention, and data-based decision making to address the needs of all students, including struggling learners and students with disabilities. Two examples of MTSS are response to intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS).

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

A three-tiered framework (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary) that provides a continuum of supports and services designed to promote appropriate behaviors and to prevent and address challenging behaviors.

evidence-based practice (EBP)

Any of a wide number of discrete skills, techniques, or strategies which have been demonstrated through experimental research or large-scale field studies to be effective. Not to be confused with an evidence-based program.

Also referred to as primary or universal prevention, Tier 1 consists of effective school-wide or classroom behavior management practices. Establishing classroom structure and teaching behavioral expectations to all students can prevent or minimize most challenging behaviors. To learn more about this, view the IRIS Modules:

Also referred to as targeted or secondary prevention, Tier 2 offers targeted supports to some students whose needs are not being met by Tier 1 supports. These include self-regulation strategies (e.g., self-monitoring) and check-in/ check-out. To learn more about self-regulation strategies, view the IRIS Module:

self-regulation strategy

Any of a number of instructional strategies designed to help students to select, monitor, and use learning strategies.

self-monitoring

A cognitive training technique that requires individuals to keep track of their own behavior and record it in writing.

check-in/check-out (CICO)

Strategy designed to decrease chronic undesired behaviors. The student checks in at the beginning of the day or the class period with a designated adult and develops a behavior goal. Throughout the day, other adults indicate progress toward meeting the goal on a point card (sometimes referred to as a “behavior report card”). At the end of the day, the student meets again with the designated adult to review the student’s progress throughout the day and to tally earned points. The parent reviews and signs the card each day. Note: This strategy should not be used to address dangerous behavior.

Also referred to as tertiary intervention or intensive, individualized prevention, Tier 3 offers an individualized support plan to the few students whose needs are not met by Tier 2 supports. This might include a functional behavioral assessment (FBA) and a behavior intervention plan (BIP). To learn more about FBAs and BIPs, view the IRIS Module:

functional behavioral assessment

A behavioral evaluation technique that determines the exact nature of problem behaviors, the reasons why they occur, and under what conditions the likelihood of their occurrence is reduced.

behavior intervention plan

A set of strategies designed to address the function of a student’s behavior as a means through which to alter it; requires a functional behavioral assessment and an associated plan that describes individually determined procedures for both prevention and intervention.

In these interviews, Pamela Glenn and Janel Brown describe how tiered systems of support are implemented in their schools.

Transcript: Pamela Glenn

As a school, we do have a tiered behavior system and we do work with the PBIS system. We have the Tier 1, where everybody has the same level of instruction and the same level of behavior expectations. Then at the Tier 2, you have those students that are not quite making it and go from like the 70, 80% down to the 20%. Then there’s the additional supports, and we have lesson plans in place to reteach the lessons for the behaviors that we’re seeing that are not being mastered. For example, if Johnny is not being safe in the classroom, it would be a moment to, “Okay, what’s going on, Johnny? We’re having this problem where everybody else is on-task and doing their work, and you’re running around. Talk to me and let’s see what’s going on. Maybe we need to put something in place for you.” And then we monitor that. At the Tier 3, it would be that 3 to 5% of students that need additional supports. Do they need an IEP? Do they have an IEP? Are we following their 504? And then honing in on what supports does the student need. Do we need to get the parents involved? And then that would be a specific behavior plan that we would put in place for that specific student. We have a lot of PBIS celebrations. Every quarter there is something that the students are working towards, be it ice cream party, a dance party, a field day. And then in between each quarter, there’s a mini celebration. It may be a T-shirt day or something that the students are working towards, and we promote that throughout the weeks leading up to. We all support each other, and everybody helps each other out so that they can participate in those celebrations.

Transcript: Janel Brown

We have MTSS, which is multi-tiered systems of support. There’s three levels. There’s Tier 1, which is the entire school. There’s Tier 2, which may be a select group of students. And then we have Tier 3, which is more one-on-one with students. And we also have PBIS, Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports. If kids are adhering to the expectations in class, they’re on task. Whatever that teacher has posted in her classroom, if they’re doing that, at one month, there’s a reward. At the end of the nine weeks, there’s a big reward. Tier 2 will be those students who need maybe just a little support academically, emotionally, socially. They may go and see the guidance counselor for social emotional learning. And, they have their little group, and they talk about things that are going on or what they need help with. Here at my site, we had a program, and anything that was talked about within that class, stayed in the class. So they couldn’t go outside of the classroom, discuss anything that we talked about, because some students did share personal things and we didn’t want it shared about campus. Tier 3 is more the one-on-one. Over the years I’ve had plenty Tier 3 students. One-on-one would be like Check-in/Check-out. I’ll have to check in with them at breakfast time, lunch time, and before they went home and sometimes in between. It was just a constant check-in activity to make sure they were on track, to make sure they were on-task if they had any issues. Perhaps they needed to just come and talk for a minute. They could come, they were allowed to get a pass and they would come and just have conversation about something that was bothering them in the moment. And those students were some of our more severe behavior students. It would get them out of the classroom for a bit to even give the classroom teacher a break and for the students to get a break.

To learn about two models of tiered systems of support, visit the following centers.

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS)—As mentioned above, PBIS is a framework that provides foundational systems and identifies key practices of Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 to improve academic and behavioral outcomes.

The Comprehensive, Integrated Three-Tiered Model of Prevention (Ci3T) is an integrative model that incorporates academic and behavioral supports, with the addition of supports to address social and emotional well-being.

By working through this module, you’ll learn more about the different phases of the acting-out cycle. For each phase, you will be introduced to some strategies and tips that can help you address student behavior proactively, appropriately, and respectfully.