How can educators recognize and intervene when student behavior is escalating?

Page 6: Acceleration

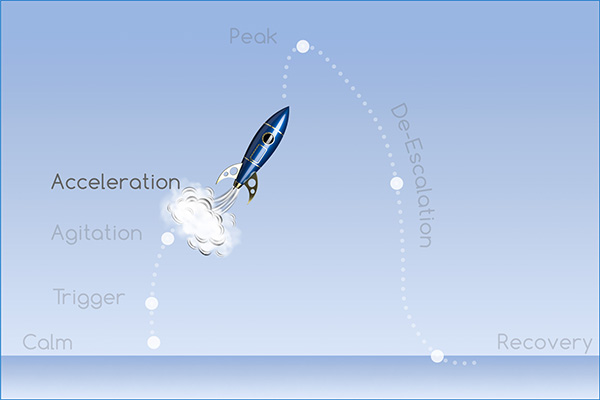

During the Acceleration Phase, student behavior becomes more focused in an effort to engage the teacher. Although the Acceleration Phase is in the middle of the acting-out behavior cycle, indicating that the behavioral concern has been building for some time, this is often when teachers first recognize that a problem is occurring.

During the Acceleration Phase, student behavior becomes more focused in an effort to engage the teacher. Although the Acceleration Phase is in the middle of the acting-out behavior cycle, indicating that the behavioral concern has been building for some time, this is often when teachers first recognize that a problem is occurring.

What a Student Looks Like

During acceleration, students engage in a variety of behaviors that can provoke the teacher and interfere with instruction. These behaviors are more intense than in the previous phase and can include:

- Questioning or arguing

- Unwillingness to rationally communicate

- Off-task behaviors that disrupt the learning environment (e.g., inappropriate noises, loud tapping)

- Refusal to work by:

- Completing required assignments but with poor quality

- Completing only a portion of the assignment

- Not completing any portion of the assignment

- Engaging other students

- Minor property destruction (e.g., ripping up a test)

In this video, note the behaviors that Ava displays during the Acceleration Phase (time: 2:03).

Transcript: Acceleration Phase

Teacher: Please close out of that site and begin working on your project.

Ava: I was looking at videos to research for your stupid class.

[Ava drops the tablet onto her desk.]

Teacher: Hey, we need to have a chat. [Motions for Ava to follow her.]

Class: Ooooohhhh!

[ Johanna Staubitz commentary ]

In this clip, Ms. Harris more directly instructs Ava to stop using the tablet. So note that the reprimand is phrased in terms of what Ava should stop doing rather than what she should do. And Ava is defensive and she calls the class stupid. She calls your class stupid, Ms. Harris. And Ms. Harris then reacts and escalates the situation to a full power struggle by saying publicly while walking away so she has to speak louder so more people can hear it that Ava and Ms. Harris need to have a chat. That implies that Ava needs to get up and follow. And so now she’s put this demand out there where both parties are going to have to dig in if they want to look like they’re in control. It’s important or it’s clear that that’s important to Ava. And we know that’s important to Ms. Harris as a teacher. But unfortunately, being put in this position, Ava’s choice between digging in and not following instructions and publicly following Ms. Harris’ directive, there is kind of a recipe for trouble. Ava, remember, is very competitive, very concerned with winning and coming out on top. So that just particular way of thinking or set of preferences is definitely at odds with a teacher strategy of saying we need to come have a chat, implying that they should go do so. So now her escalation has more to do more to it than simply the difficulty of that transition from high preferred activity to low preferred activity. Now she’s in a relatively public power struggle with Ms. Harris.

Strategies To Implement

Managing the student’s behavior and preventing further escalation is imperative during this phase of the acting-out cycle. Below is a list of strategies and tips to defuse a student’s behavior.

| Strategy | Tips |

| Remain neutral when interacting with the student. |

Note: Because the student is directly attempting to engage the teacher, this can be a tense or stressful situation. |

| Give the student an individual prompt or redirection. |

|

| Allow the student adequate time to respond. |

|

| Reinforce the student for compliance or on-task behavior. |

Note: After praising a student for demonstrating the expected behavior, request additional, limited engagement in the activity. Encouraging the student to solve the next problem or read the next paragraph can defuse challenging behaviors and allow the student to refocus on the task at hand. |

The teacher’s response to a student’s behavior in this phase can greatly influence whether a student returns to the Calm Phase or escalates to the Peak Phase. Although further escalation is sometimes unavoidable, this is the teacher’s last chance to implement strategies to interrupt the acting-out cycle. In this video, Ms. Harris intervenes effectively to interrupt the acting-out cycle at the Acceleration Phase and helps Ava return to the Calm Phase (time: 2:34).

Transcript: Acceleration Phase with De-escalation Strategy

Teacher: Hey, I see what you’re doing. Please close out of that site and begin working on your project.

Ava: I was trying to research for your stupid class.

[Ava drops the tablet onto her desk.]

Teacher: Hey, Ava, I see that you’re getting a little frustrated. Is there anything that I can help with?

Ava: We went from a fun game to this. I’m bored.

Teacher: Yeah, I understand. I like the review games too, especially when I have such a great student as a champ. Let’s look through your list of people so that we can see who you have, and honestly, some of these people have some pretty cool stories. And because you’re so creative, I think that you’ll do a really good job coming up with something.

[ Johanna Staubitz commentary ]

This time though Ava is still demonstrating behavior associated with Acceleration saying “stupid class,” tossing the tablet aside. Ms. Harris steps in in a more effective way. Instead of moving away from Ava, Ms. Harris moves in closer so that she could speak to her in a way that is much more private. Again all, you know, all students are perceptive to their peers’ perceptions of them and are sensitive to that. But this is particularly important at the secondary level. got to protect students’ privacy if we want to help them manage their emotions in a situation like this. So it’s really nice that Ms. Harris moves in closely. And she listens to what Ava says also. And at this point, Ms. Harris realizes what the trigger was. And she made an empathetic statement saying that kind of transition can be hard for her too, which it’s nice. Validate your students’ feelings when they share them or even validate what you think may be their feelings if you’re making an observation because then they know you’re on their team and you recognize what it is they’re experiencing. And this can just de-escalate their emotionality, which is a big part of their escalation of their external and observable behavior. So after that, Ms. Harris offers a suggestion like, “Hey, there are some people on this list who have some pretty cool stories. I think you actually might be into it.” So now they’re kind of they’re on the same team and she’s encouraging Ava and framing up this assignment in terms of what’s going to be good for Ava about it, which is really smart. “These are cool stories. You like cool stories and you’re really creative.” So she also highlights some of Ava’s strengths, as she reiterates what the task demand is before moving on.

Though it can be quite difficult, a teacher must put away his pride during this phase of the acting-out cycle. Remember, at this point, the situation is not about the teacher but about the student. When dealing with a student in this phase, the teacher must always consider the student’s dignity. The teacher can respectfully address acting-out behaviors by:

- Using the student’s name when prompting or redirecting

- Focusing on the behavior not the student

- Speaking to the student discreetly or privately

- Speaking to the student at eye-level

Kathleen Lane explains more about how a teacher can interrupt the acting-out cycle during the Acceleration Phase. And although it may seem counterintuitive, a teacher may need to overlook some minor behaviors to de-escalate the situation. Next, Pamela Glenn and Janel Brown describe common mistakes new teachers often make when addressing challenging behavior.

Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Professor

Department of Special Education

Associate Vice Chancellor for Research

University of Kansas

(time: 2:53).

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Without any kind of awareness training about the acting-out cycle whatsoever, this is typically the stage when teachers would begin to know for sure that there’s a problem. And this is when the student is trying to take you on as a teacher. And oftentimes in this phase of acceleration, the students are trying to engage you in an argument, and it might come across like, “This is so boring,” or, “I can’t believe I have to do this again,” and they’re intentionally trying to provoke you or capture your attention. Your typical response might be to say something like, “You need to do this because I told you this is what needs to be done.” And then you might find yourself engaged in an argument with a fifteen-year old. But at this point, it is critical that you not engage in sarcasm that way. And instead, we want to reach deep, and we want to show empathy towards them and find a constructive way to move that conversation forward without embarrassing them. So you might say something like, “I know you’re really upset right now, but I really need you to start these problems.” And maybe your intervention at that point is as simple as taking a highlighter and then underlining the first three problems. And then you can say to them, “When you get done with these first three, go ahead and check them with a partner and I’ll be right back to check on you after that.” Even if they make a comment when you start to walk away, that is still not the ideal time to take them on. You’re giving them an opportunity to save a little face there. And this is one of those situations where you’re going to lose the battle to win the war type of a thing. Because if you attempt to engage them, then you’re likely to propel them into that next stage. And instead, when you start to walk away and they make somewhat of a snide comment, just keep going.

Another thing that will show up during this time is that for many students, they will engage in what’s called partial compliance. So if you tell them to do an assignment, they’ll do it in a very, very sloppy or rushed way and just turn it in and think, “Okay, that’s good enough.” And sometimes as a teacher, this is hard to do, but the ideal response might be to say something like this: “I appreciate your turning that in. However, as I’m looking over this last one, I simply can’t read it. Could you go back and redo just this one so I can make sure that I can give you full credit if this answer is correct.” But if you were to go back to them and say, “I need you to redo this whole thing” at that very moment, you would likely push them over the edge and they may move even further up the acting-out cycle into that peak behavior. So in summary, the best way a teacher can interrupt the acceleration phase is to offer a prompt and then walk away. In other words, make the request known and then give them an opportunity to get back on track. And then as soon as they do get back on track, that’s the time you want to give them immediate acknowledgment or reinforcement. As simple as “I really appreciate you getting back on track, that’s awesome.”

Transcript: Pamela Glenn

I think some of the most common mistakes that new teachers make is getting in a power struggle with a kid. Don’t do it. You’re not going to win. It’s not productive at all. There’s something about knowing when to not speak and let the child get it out. And then wait for the child to have completely depleted themselves [laughs] and then move in. I’ve seen more teachers: Child gets angry, teacher gets angry. And it’s just a spiral of a disaster. My biggest advice is do not get in a power struggle with a child, you’re not going to win. When they are talking and they’re talking back, you’ve set your expectation. That’s when you have to be calm. “This is not the behavior that I expect.” And you’ve got to give them a minute, because if you think about it, when you’re upset, you can’t rationally think through what’s going on to respond in the moment. I know I need a minute to calm down. Especially if they’re in front of their friends, they’ve got to save face. “You need a minute. Go take a minute. I’m not going back in for an argument with you. So just take a minute.” And then afterwards we address, “That’s not how you talk to me.” So, we always address the behavior. Then we look at why were you behaving like that? It’s never a case of “I can throw a chair, and she’s not going to do anything.” We’re going to talk about it. The other thing that I think is also a common mistake that teachers make is we have a lot of preconceived ideas about what a certain type of student is going to do. I think sometimes we’ve already decided in our minds ‘This student is going to do this. I’m going to treat them like this.’ The student’s been treated like that. They lash back and then it’s a never-ending cycle of what is expected or how they’ve been treated. I think everybody just has to judge the child based on who they are in the moment and set the expectation. The children will rise to the expectation if you help them.

Transcript: Janel Brown

As a new teacher coming in, you really cannot take anything personally from your students as far as behavior, lashing out. These kids, they go through so much, and they just don’t know how to express themselves properly. You have to understand your kids’ background, where they’re coming from, what they’re dealing with. Some are dealing with homelessness. Some of them are dealing with not having enough food to eat at home. Dad’s missing, Mom is missing, drugs, just all types of things. The best thing that you can do, as a new teacher coming in, just let a student know that “I’m here for you. If you ever need to talk or anything, I’m not going to force you to talk, but if you ever feel that you want to tell me what’s going on, I’m here to listen. I’ll try my best to do what I need to do to get the help that you need for whatever your issue is.” Just have compassion for the students. If Johnny did something yesterday, don’t hold it against him tomorrow. You give him new grace and new mercies. Just like we get new graces and mercies every day, we have to extend that to our kids as well. Love them. But if you’re constantly just fussing and yelling, and Johnny can’t ever do anything right, this child may be going through this at home. And then at school, which is supposed to be his safe place, he’s getting the same thing. He’s just at a loss. So, yes, grace, mercy, compassion. Don’t take it personal.

Activity

Review the below videos.

Transcript: Video 1—Acceleration Phase

[Sam rubs his eyes and is not working.]

Transcript: Video 2—Acceleration Phase with De-escalation Strategy

[Sam rubs his eyes and is not working.]

[Teacher uses her cell phone to text another teacher and grabs a book.]

Teacher: Hey Sam, Ms. Gonzalez just texted me about needing this book for her next class. Can you go ahead and take it to her? I said she could use it for the next period.

[Sam nods.]

Teacher: Thank you.

Now that you have reviewed the videos, respond to the following items.

- Compare and contrast how Ms. Harris responds to Sam’s behavior in both videos.

- What is another strategy that Ms. Harris could have implemented to de-escalate Sam’s behavior?

You may type your answers in the field below the video. However, this field is provided for reflection purposes; your answers will not be available for download or printing.

Now that you’ve had a chance to reflect, listen to Johanna Staubitz’s feedback (time: 1:53).

Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

Associate Professor

Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

Transcript: Johanna Staubitz, PhD, BCBA-D

In these videos, Ms. Harris responds to Sam’s behavior in two pretty different ways. In the first one—and recall that his behavior is pretty passive, so it’s still easy to miss—Ms. Harris doesn’t intervene at all, even though those signs of a problem are persisting and he looks increasingly distressed, heavy sighs, rubbing his face, total disengagement from the work, which also suggests that Sam is probably more stressed and emotional on the inside in addition to what we’re seeing on the outside. And that’s why what Ms. Harris does in the second video is such a nice fit. Sam, at this point, probably needs a break in addition to a restatement of the instructions. So our problem has been compounded because this has gone on for a while and he’s emotional along with needing to know what to do. What Ms. Harris does is gets her cell phone out, picks up a book and everything, and then makes her way over to Sam and says, “Hey, I need somebody to run this book next door. Can you do it?” And he happily does so because right now he needs a break in addition to clarification on what it is he supposed to do.

There are other things that Ms. Harris could have done to de-escalate Sam’s behavior at this point besides just giving the break. And honestly, she’ll probably still have to do these things once he comes back from delivering the book because, remember, that initial trigger is still not resolved. He doesn’t know what to do. So Ms. Harris could ask him, “Hey, Sam, do you know what the first thing is you need to do to get started?” Or just give him some other form of an individual prompt or redirect. “Hey, the first thing you need to do is start reading this and taking notes.” And that would be enough. Even better, she could write down the steps for him and check for understanding, and that would likely de-escalate Sam’s behavior. She could also offer him choices as part of that redirect, “Hey, I could write the instructions down for you or you could ask me questions about them.” Anytime we can incorporate choice into an interaction with students, we should.