How do teachers differentiate instruction?

Page 8: Evaluate and Grade Student Performance

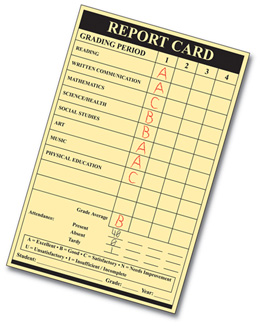

In any classroom, the teacher is expected to document students’ performance. At regular intervals (e.g., six weeks, nine weeks), the results of this evaluation are shared with students and their parents in the form of a report card. When they are first introduced to the concept of differentiated instruction, some teachers, parents, and students might consider it unfair for all students to be evaluated and graded using the same set of criteria when some students are working on complex or advanced tasks and others are learning foundational skills. In other words, they believe that the lower-performing students might receive higher grades than they deserve. However, this belief is often dismissed once it is understood that one of the major goals of a differentiated classroom is to help all students to succeed. Success is defined as a demonstration of growth toward the mastery of a given content or a skill. Because students in a differentiated classroom are often working on different tasks and completing different products to show mastery, several questions arise:

In any classroom, the teacher is expected to document students’ performance. At regular intervals (e.g., six weeks, nine weeks), the results of this evaluation are shared with students and their parents in the form of a report card. When they are first introduced to the concept of differentiated instruction, some teachers, parents, and students might consider it unfair for all students to be evaluated and graded using the same set of criteria when some students are working on complex or advanced tasks and others are learning foundational skills. In other words, they believe that the lower-performing students might receive higher grades than they deserve. However, this belief is often dismissed once it is understood that one of the major goals of a differentiated classroom is to help all students to succeed. Success is defined as a demonstration of growth toward the mastery of a given content or a skill. Because students in a differentiated classroom are often working on different tasks and completing different products to show mastery, several questions arise:

- How will the teacher fairly evaluate each student’s performance?

- How will the teacher assign grades?

Evaluating Performance

Though students will work on different activities and demonstrate their knowledge through a variety of products, teachers can accurately evaluate student performance using one of several recommended methods:

Though students will work on different activities and demonstrate their knowledge through a variety of products, teachers can accurately evaluate student performance using one of several recommended methods:

- Rubrics: A rubric is an objective set of guidelines that defines the criteria used to score or grade an assignment. It describes the requirements of the assignment and clearly outlines the points the student will receive based on the quality of his or her work. Teachers can give students the rubric in advance to help them understand the requirements and expectations for the assignment. Even if the students are completing a variety of products to demonstrate their knowledge of the same content or skill, teachers can use the same rubric for grading all of the students’ products.

The rubric below was developed to grade a product demonstrating knowledge about the burial customs of ancient Egypt. Note that the rubric can be applied to any type of product that the students choose to complete.

1. Define the learning objective

Example: The students will learn about and present information about the burial customs of ancient Egypt.

2. Identify the concepts or skills students need to demonstrate

Example: For their presentations on ancient Egypt, the students will need to demonstrate:

- Organization (e.g., logical structure)

- Subject knowledge (e.g., mention of key points)

- Level of detail (e.g., detailed descriptions)

- Use of multiple sources (e.g., four references)

3. Identify the levels of performance and their point values

In general, it is better to use no more than seven levels, and no fewer than three. Teachers can use a zero as the lowest level of performance, if they choose.

Example: For the Egyptian presentation, the levels of performance are: 1=poor, 2=average, 3=excellent

4. Identify the criteria for each level of performance and create table

For the Egyptian presentation, see the table below:

Presentation on ancient Egyptian burial customs 1 = poor 2 = average 3 = excellent Organization Student presents information in an illogical and uninteresting way Student presents information in a logical or interesting way Student presents information in a logical and interesting way Demonstration of subject knowledge Student mentions or represents three or fewer of the following:

- Sarcophagus

- Canopic jars

- Mummification

- Tombs

- Burial mask

- Funerary art

Student mentions or represents at least four of the following:

- Sarcophagus

- Canopic jars

- Mummification

- Tombs

- Burial mask

- Funerary art

Student must mention or represent all six of the following:

- Sarcophagus

- Canopic jars

- Mummification

- Tombs

- Burial mask

- Funerary art

Level of detail Student presents basic facts of subject knowledge items with little detail Student presents some detailed descriptions or representations of subject knowledge items Student presents very detailed descriptions or representations of subject knowledge items Use of multiple sources Student uses two or fewer references (in addition to the textbook) Student uses three references (in addition to the textbook) Student must use four references (in addition to the textbook) 5. Create a grading system based on possible points earned

For the Egyptian presentation, the grading system is:

Points Grade 12 A+ 11 A 10 B+ 9 B 8 C+ 7 C 6 D+ 5 D 4 F - Portfolios: A portfolio is a collection of artifacts, or individual work samples, that represent a student’s performance over a period of time. In general, this type of assessment allows teachers to more accurately evaluate a student’s mastery of content or a skill than a single assessment such as a test that captures one moment in time. A portfolio also allows a student to reflect on his or her performance over time and to perhaps establish future goals.

Different types of portfolios serve different purposes. Common types of portfolios include:

Did You Know?

Working folders are not the same thing as portfolios. They are a simply a place to store a student’s work.

- Achievement—a collection of representative work samples that demonstrates how a student is performing at a given point in time

- Growth—a collection of items from before, during, and after learning to show progress across time

- Project (or process)—a collection of artifacts that documents the process used or the steps taken to complete a project

- Competence—a collection of items that documents the highest level of achievement in a given area

- Celebration (or showcase)—a collection of items that the student is proud of

First, the teacher needs to identify the type of portfolio that would best evaluate the student’s performance. Next, to use the portfolio effectively, the teacher needs to address the factors in the table below.

Learning objectives - Define the learning goal(s) or objective(s) that the portfolio will address, or, in the case of project portfolios, the stages of the process.

- Clearly state the learning goals(s) or objectives(s) using language that students and parents can easily understand.

Inclusion criteria - Specify the types of artifacts that should be included (this may vary by the type of portfolio).

- Decide who will select the artifacts for inclusion (i.e., student, teacher, both).

- Indicate the number of artifacts to include.

Self-reflection - Include an annotation (or comment) for each item selected for the portfolio. The portfolio creator can write down things such as the learning goal or objective that is being addressed, why he or she chose the item, something that was learned, or what he or she needs to improve.

- Require students to review the items in their portfolio as a whole and write down things such as what they have and have not learned, how much they have improved, what did and did not work, and what they need to work on in the future.

Communicating - Determine who the audience will be (e.g., teacher, parents, other students).

- Discuss the contents of the portfolio when conferencing with a student.

- Consider sending the portfolios (perhaps with the exception of project folders) home each grading period to share with the parents.

Organization - Identify artifacts the students can include. Work samples may include hard copies, electronic copies, audio recordings, videos, and photographs of projects that cannot be stored in a portfolio.

- Determine how to organize the artifacts. These items may be housed in folders, binders, notebooks, etc.

- Determine how and where to store the students’ portfolios so that they are easily accessible by the students. These may be stored in file drawers, crates, boxes, etc.

- Provide time for students to select artifacts and write annotations and self-reflections.

Teachers can examine the portfolios to evaluate student performance, but how they conduct that evaluation depends on the type of portfolio. The graphic below suggests some evaluation guidelines for each type.

Growth

Achievement

Competence- Evaluate artifacts prior to or during the selection process.

- Examine the annotations students write for each item and their self-reflections for the overall portfolio.

Project- Evaluate the final project.

- Use the annotations and self-reflections as an assessment.

Celebration- Evaluate annotations and self-reflections only.

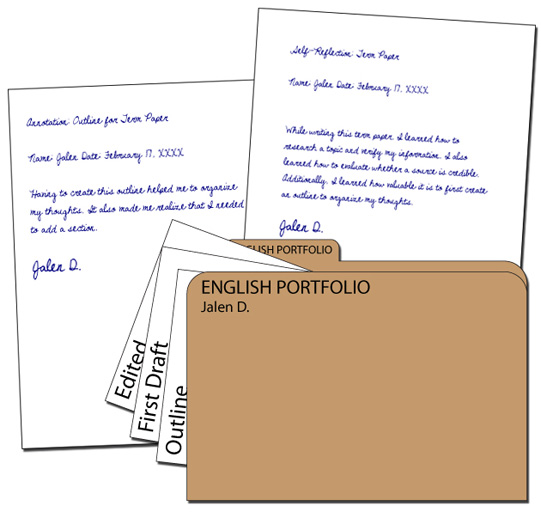

In the example below, a twelfth-grade English teacher has assigned a project portfolio so that she can evaluate whether the students have mastered the process of writing a research paper. The teacher asks that the students include a number of items to demonstrate that they understand the steps required to write a term paper (e.g., list of sources, outline, first draft, edited version). For each artifact, the students must include an annotation. Additionally, when students turn in their final term paper, they will include a self-reflection describing what skills they have developed during the process.

A graphic represents the English portfolio belonging to a twelfth-grade student named Jalen D. Inside the portfolio are a number of pages. One is labeled “Edited,” another “First Draft,” and a third “Outline.”

Jalen D. has also written an annotation for his term paper outline. His annotation reads as follows:

Annotation: Outline for Term Paper

Name: Jalen Date: February 17, XXXX

Having to create this outline helped me to organize my thoughts. It also made me realize that I needed to add a section.

Jalen D.

Finally, Jalen D. has written a self-reflection to sum up the experience of writing his term paper. His self-reflection reads as follows:

Self-Reflection: Term Paper

Name: Jalen Date: February 17, XXXX

While writing this term paper, I learned how to research a topic and verify my information. I also learned how to evaluate whether a source is credible. Additionally, I learned how valuable it is to first create an outline to organize my thoughts.

Jalen D.

- Self-assessment: Student self-assessment is the process of students using specific criteria to evaluate and reflect on their own work. In doing so, students become more responsible for their own learning and may be more prepared to work with the teacher to develop individual learning goals. For students to effectively evaluate their own work, teachers should provide them criteria to evaluate themselves against.

Self-evaluation can be an effective means of gauging performance and can have a positive effect on student outcomes. However, for students to evaluate their own work accurately and benefit from the process, teachers must first instruct them how to do so. Teachers might want to start by having the students complete short self-evaluations on small assignments (e.g., daily homework). In general, for student self-assessment to be effective, teachers should:

Self-evaluation can be an effective means of gauging performance and can have a positive effect on student outcomes. However, for students to evaluate their own work accurately and benefit from the process, teachers must first instruct them how to do so. Teachers might want to start by having the students complete short self-evaluations on small assignments (e.g., daily homework). In general, for student self-assessment to be effective, teachers should:- Allow students to participate in developing the criteria that will be used to evaluate their work.

- Demonstrate how to apply the criteria by providing examples and modeling.

- Offer feedback on their self-assessments and discuss any differences of opinion. Feedback can be provided by the teacher or a classmate.

- Using the self-evaluation data, help students develop appropriate learning goals.

Teachers can provide students with rubrics and checklists with which to self evaluate their work. Teachers also might want to use strategies such as those highlighted in the table below.

Strategy Suggestions Surveys - Use a Likert scale.

- Use text (e.g., disagree, unsure, agree) or symbols, depending on the students’ reading level.

Self-reflection prompts - Provide fill-in-blank statements or a list of questions (e.g., Can I explain this concept to someone else?).

Journals - Provide sample prompts (e.g., I learned…, I’m having difficulty understanding…).

Interactive notebooks - Allow students to write about what they have learned, including a personal reflection, and then respond.

Adapted from Wormeli (2006). - Achievement (i.e., how the student is performing in relation to expected grade-level goals)

- Growth (i.e., the amount of individual improvement over time)

- Habits (e.g., participation, behavior, effort, attendance)

Assigning Grades

In addition to evaluating performance, teachers must also assign grades for each instructional period. Typically, teachers consider three factors when they assign grades:

In a traditional classroom, teachers usually report one grade that reflects all three factors. Although achievement is important in a differentiated classroom, growth is also critical; it is a measure of success and teachers want to communicate to students and to parents how much growth the student has experienced. In a differentiated classroom, teachers grade these factors separately. They report grades based only on achievement and report information about growth and habits in other ways, such as in the notes section of the report card, sending a letter or email home containing this information, or discussing at a parent-teacher conference.

For Your Information

In a traditional classroom, it is often the case that students with the greatest ability easily achieve the top grades with little effort, while students who struggle often receive poor or failing grades even if they have worked hard and shown great improvement. This frequently results in the top students not applying themselves because they can easily master the work with little or no effort and in the struggling students giving up because no amount of effort will lead to success.

When they assign grades, teachers should keep several principles in mind. First, teachers should understand that an assessment is a means of collecting information about their students and that every assessment does not have to be graded. Second, grades should be based on a student’s performance in relation to grade-level standards. Next, as mentioned above, grades should only reflect student achievement, not student growth or habits. Finally, students should be graded against established criteria and not in relation to the performance of their peers. In addition to these principles, teachers should consider practices related to grading. Click on each item below to learn more about how to address it in a differentiated classroom.

The primary purpose of preassessments and formative assessments is to guide instruction. Preassessments and homework should never be graded. Formative assessments should rarely be graded, and only when students are informed ahead of time. The reason for this is that, if teachers grade these types of assessments early in the grading cycle, some students’ grade averages will be lowered because they are unable to perform well on a task that they have just been introduced to. Instead, summative assessments should be graded to determine whether students have mastered the content.

formative assessment

A system of providing continual feedback about preconceptions and performances to both learners and instructors; an ongoing evaluation of student learning.

summative assessment

An evaluation administered to measure student learning outcomes, typically at the end of a unit or chapter. Often used to evaluate whether a student has mastered the content or skill.

Grades should be an accurate reflection of student achievement. Teachers should not adjust a student’s grades either higher or lower based on other factors such as effort, bonus points, and behavior. Similarly, teachers should not grade on curve.

Because students learn at different rates, some might not perform well on the summative assessment. However, this does not mean that students cannot master the content or skill; they might just need more time. Teachers should give students another chance to demonstrate mastery without being penalized (e.g., deducting points for a second attempt). Teachers should give students full credit if they master the content on subsequent attempts.

Because students learn in different ways, some require more supports to successfully learn content or a skill and to demonstrate their knowledge. If teachers provide supports (e.g., graphic organizers) to help students master the material, they should also provide these same supports when students are being assessed (without adjusting the grade).

Assignments or tests evaluate students’ mastery of specific content or skills. Although typically not recommended in a differentiated classroom, if a teacher awards extra credit or bonus points, they should only be awarded if the extra credit assignment or bonus activity assesses this same content. If extra credit assignment or bonus point items are unrelated, students’ grades will be inflated and not an accurate reflection of mastery.

When cooperative learning activities are used to teach students about a topic, the teacher should not grade this activity. Teachers should avoid assigning a single grade to all of the students who work together on a group project because such grades will not reflect an individual student’s mastery of the topic at hand.

cooperative learning

Instructional arrangement in which heterogeneous (mixed-ability) groups are employed as a method of maximizing the learning of everyone in those groups; also helps students to develop social skills and has been demonstrated to yield especially favorable results for students in at-risk groups, such as those with learning disabilities.

Traditionally, teachers record a zero for students who do not turn in an assignment. Even for students who generally receive good grades, a single zero can significantly lower their overall average. This is also true for students who receive a very low grade on a test or assignment (e.g., 20%). Some teachers who differentiate instruction record a grade that will indicate that the students are not proficient in a given topic (e.g., 50% or 60%) without skewing the student’s overall grade average.