What should teachers understand to facilitate success for all students?

Page 5: Language Considerations

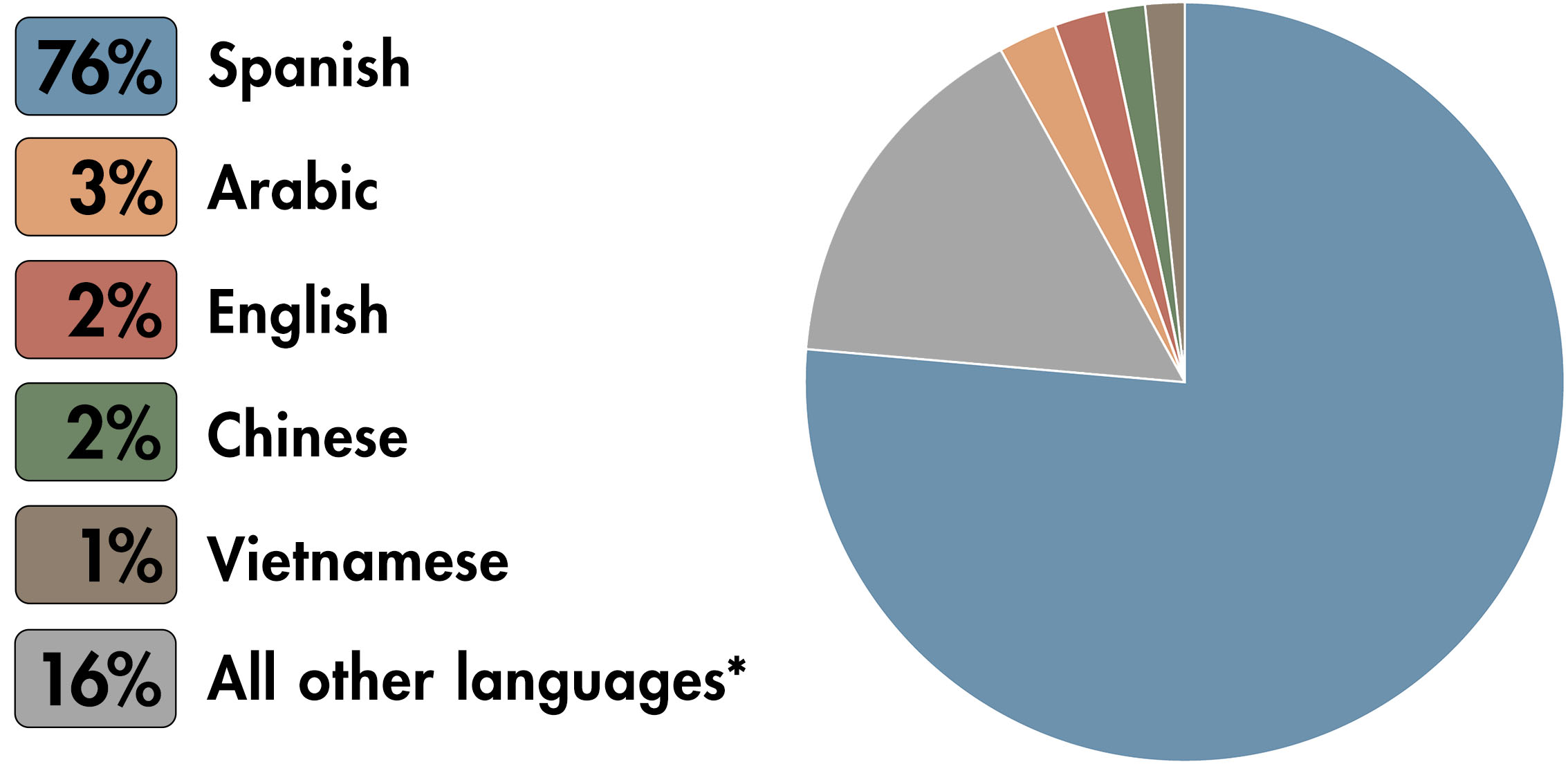

Today’s classrooms are often comprised of students who are fluent in English, learning English as a second language, or bilingual. Approximately one in 10 students in the United States (ages five to 17) speaks a language other than English at home or speaks English with difficulty. This equates to more than five million students. These students are often referred to as English learners (EL), English language learners (ELL), or students with limited English proficiency (LEP)—although the last two terms are used less frequently. Across the nation, more than 400 languages are spoken in schools. Spanish is the most commonly reported home language of ELs, representing approximately 76% of all ELs and 8% of all public school students. As noted in the graphic below, the other top home languages include Arabic (3%), English (2%), Chinese (2%), and Vietnamese (1%).

Today’s classrooms are often comprised of students who are fluent in English, learning English as a second language, or bilingual. Approximately one in 10 students in the United States (ages five to 17) speaks a language other than English at home or speaks English with difficulty. This equates to more than five million students. These students are often referred to as English learners (EL), English language learners (ELL), or students with limited English proficiency (LEP)—although the last two terms are used less frequently. Across the nation, more than 400 languages are spoken in schools. Spanish is the most commonly reported home language of ELs, representing approximately 76% of all ELs and 8% of all public school students. As noted in the graphic below, the other top home languages include Arabic (3%), English (2%), Chinese (2%), and Vietnamese (1%).

Most Spoken Languages in ELs’ Homes

*This category encompasses all other languages, each representing less than 1% of languages spoken in ELs’ homes.

Note: English is reported by EL students as the third most common home language. This might be attributed to multilingual households or households where a student was adopted from another country.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics. (2024). English learners in public schools. Condition of Education. https://nces.ed.gov/programs/coe/indicator/cgf.

Why Language Matters

Because the enrollment of ELs continues to increase, teachers need to be adequately prepared to work with these students. Educators who understand the developmental language stages are more likely to be better equipped to provide appropriate and differentiated instruction to English learners. Second language proficiency develops incrementally, somewhat like first language development. The table below summarizes the five stages of second language acquisition.

| Stage of Second Language Acquisition | Description of Language Capabilities |

| Stage I: Silent/Receptive or Preproduction Stage (up to six months) | Students typically maintain a silent period. When they interact, they tend to do so by gesturing, nodding, or using yes–no responses. |

| Stage II: Early Production Stage (can continue for an additional six months after Stage I) | Students can speak using one- or two-word phrases and can respond to simple questions (e.g., “who?” or “what?”) to indicate their understanding of novel information. |

| Stage III: Speech Emergence Stage (can last up to one year) | Students employ short phrases and simple sentences, though difficulty with language usage may sometimes inhibit their ability to communicate. |

| Stage IV: Intermediate Language Proficiency Stage (can take another year after Stage III) | Students can formulate longer and more complex statements, request clarification, and express their own thoughts and opinions. |

| Stage V: Advanced Language Proficiency Stage (can require five to seven years to gain proficiency) | Students can use English in a manner similar to their native English-speaking peers. |

Note: In each of these stages, the student’s receptive language (i.e., understanding) is generally better than their expressive language (i.e., speaking).

As students progress through these stages, they develop two types of language proficiency:

- Basic Interpersonal Communicative Skills (BICS)—This refers to a student’s ability to understand basic conversational English, sometimes called social language. At this level of proficiency, students are able to understand face-to-face social interactions and can converse in everyday social contexts. These social language skills—generally acquired in approximately two years—are sufficient for early educational experiences but are inadequate for the linguistic demands of upper elementary school and beyond. Students acquire this social language by interacting with their peers, family members, and playmates.

Example: Maria, who has lived in the United States for only a few months, can already understand her peers when they ask, “Maria, do you want to sit with us?” Maria has learned this quickly because they ask her the same question on a daily basis and use physical gestures to help her understand.

- Cognitive Academic Language Proficiency (CALP)—This refers to a student’s ability to effectively understand and use the more advanced and complex language necessary for success in academic endeavors, sometimes referred to as academic language. Students typically acquire CALP in five to seven years, a period during which they spend a significant amount of time struggling with academic concepts in the classroom.

Example: A student like Maria, who has only been in the United States for a few months, might find it difficult to understand the content-related terms discussed during Mr. Bennett’s science lesson (e.g., the term photosynthesis). She might also struggle with instruction-related terms such as compare and contrast. Finally, her difficulty could be compounded if she hasn’t learned these concepts in her first language.

| Social Language (BICS) |

|

| Academic Language (CALP) |

|

For Your Information

Because social and academic language often develop at the same time, proficiency in social language does not have to be achieved before teachers introduce academic language.

English learners often struggle to comprehend what the teacher is saying. To get a better sense of what these students might be experiencing, watch the movie below and try to follow along with the teacher’s lecture in Portuguese (time: 0:26).

Were you able to understand the lesson? Imagine how frustrating and exhausting it is for students who are unable to comprehend what their teacher is saying. To further understand what students might experience, translate the following sentences using any foreign language skills you might have.

1. My name is ____. What is your name?

2. I like your sweater. Where did you get it?

3. This weekend I went to a movie and out to dinner with my friends.

4. Answer questions 12 through 15 on page 216 in your textbook for homework tonight.

5. Look at the diagram on Page 96. Which figure has the greater area, the quadrangle or the octagon? Write the formula for determining each area, then calculate each area and show all of your work.

6. Photosynthesis is the process through which plants change the sun’s light into food, consuming carbon dioxide and producing oxygen.

When educators don’t understand the difference between social and academic language, misperceptions can occur. For example, a teacher might overhear a student talking with friends on the playground (social language) and assume they are proficient in English. However, the teacher is confused when the student struggles to communicate and understand content in class (academic language). A lack of awareness about the difficulty of academic language might lead a teacher to believe that the student is not trying or that they have learning difficulties, which could potentially result in:

- Low expectations for students

- Instruction that lacks appropriate scaffolds and supports

- Inappropriate referrals to special education

The late Janette Klingner talks about some common misperceptions teachers have about English learners (time: 3:25).

Janette Klingner, PhD

Former Professor, School of Education

University of Colorado, Boulder

Transcript: Janette Klingner, PhD

We tend to think of English language learners as being sequential bilinguals or, in other words, speaking a different language than English at home and then learning a language, such as English, when they start schools. But in fact, the majority of English language learners in the United States are actually simultaneous bilinguals, meaning that they actually speak another language than English, as well as English, in their homes and so start school speaking some of both. Because if you assess that child in his or her presumed home language, you might find that scores are low. Same thing with English. You might test the child and find out scores are also low. But if we combine all the words the child knows, we find out that the total number is actually higher than his or her peers who are monolingual in one language or another.

Another misconception is that instructional frameworks developed for students in English are appropriate for developing skills in a second language. I think it’s important to realize that although there are similarities, there also are very key differences in learning to read in a second language, and that instruction needs to take that into account. Another misconception is that the more time students spend in English instruction, the faster they will learn English. We know from research that some instruction in the native language actually helps students acquire English faster. Another misconception is that all English language learners learn English at about the same rate. And in fact, what we know is that the length of time students take to acquire English really varies a great deal and really depends on a lot of different factors. Another misconception is that errors are problematic, that when children seem to be confusing language that it’s problematic to be code-switching or mixing English and Spanish. In fact, we know that they are a positive sign that the student is making progress, and that’s very much a normal part of the language acquisition process to be drawing from both grammatical structures, vocabulary, in whatever languages are available to the child. So they should not be considered errors but rather a sign of progress and a natural thing to be doing. I think, perhaps, the most important one of all is the sense that children who are not yet fully proficient in English somehow aren’t as intelligent and also that they’re not ready to engage in higher-level thinking activities until they learn basic skills. What we see in schools is this being played out, where kids need to go through drill, focus on basic skills sort of over and over again until they are asked to engage in higher-level thinking related to content learning, etc. Clearly, English language learners are every bit as intelligent as fully proficient peers, and we need to structure our instruction accordingly.

Research Shows

- English learners perform better when information is scaffolded in their first language.

(August & Shanahan, 2006) - Reading instruction in a student’s primary language promotes higher levels of reading achievement in English and in their primary language.

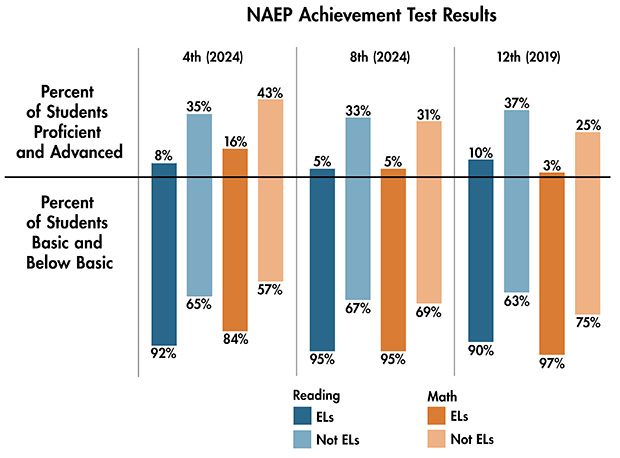

(Goldenberg, 2008) - ELs do not perform as well academically as students who are not English learners. To measure student academic achievement in the United States, the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) administers reading and mathematics achievement assessments to fourth- and eighth-grade students each year and to 12th-grade students every four years. Student performance indicates the degree to which they have acquired the knowledge and skills expected at their grade level. The results are categorized into one of four levels: Below Basic (little mastery), Basic (partial mastery), Proficient (mastery), and Advanced (beyond mastery). The 2024 reading and mathematics results for fourth and eighth grade (and the 2019 results for 12th grade) are compared in the table below for ELs and those categorized as not being ELs.

Source: National Assessment of Education Progress. (2020, 2025). NAEP achievement test results. The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov

This bar graph illustrates the results of the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading and mathematics achievement test for fourth and eighth grade as well as the 2019 data for 12th grade. The table is divided into three sections—one for fourth-grade results, one for eighth-grade results, and one for 12th-grade results. There is a horizontal line running through all sections. The portion above the line is labeled “Students Proficient & Advanced,” while the lower is labeled “Students Basic & Below Basic.”

The test results are displayed for four categories of test takers: “ELs in reading,” “Not ELs in reading,” “ELs in math,” and “Not ELs in math.”

For fourth graders, 8% of ELs in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 92% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in reading, 35% are Proficient & Advanced and 65% are Basic & Below Basic. For ELs in math, 16% are Proficient & Advanced and 84% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in math, 43% are Proficient & Advanced and 57% are Basic & Below Basic.

For eighth graders, 5% of ELs in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 95% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in reading, 33% are Proficient & Advanced and 67% are Basic & Below Basic. For ELs in math, 5% are Proficient & Advanced and 95% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in math, 31% are Proficient & Advanced and 69% are Basic & Below Basic.

For 12th graders, 10% of ELs in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 90% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in reading, 37% are Proficient & Advanced and 63% are Basic & Below Basic. For ELs in math, 3% are Proficient & Advanced and 97% are Basic & Below Basic. For Not ELs in math, 25% are Proficient & Advanced and 75% are Basic & Below Basic.

What Educators Can Do

ELs often receive services from a bilingual or English as a Second Language (ESL) teacher to help them learn English. At the same time, general education teachers should promote the success of EL students in mastering academic content by using effective supports and strategies to strengthen students’ learning outcomes.

Sheltered instruction involves integrating academic content with English language instruction and incorporating support for language and content objectives into lessons. This includes facilitating student comprehension by:

- Speaking more slowly and clearly

- Monitoring vocabulary

- Using multimodal techniques (e.g., visuals, role-playing, video)

- Keeping clauses and sentences short

Provide more context to make a difficult task that requires higher-level thinking skills less cognitively demanding. Teachers can do this by providing:

- Visual cues to help students learn new words or content. For example, teachers can label items around the room both in English and in the students’ native languages.

- Real objects, pictures, and graphics that support the information presented in an existing lesson plan (e.g., identifying the basic parts of plants)

- Manipulatives that help students understand abstract concepts (e.g., fractions)

Using information gathered from students, their families, or a bilingual liaison, build on or connect instruction to students’ knowledge, cultural backgrounds, and previous experiences to help them understand new concepts and vocabulary terms. For instance, educators can:

- Use graphic organizers and other visuals to show the connections between students’ prior experiences and new knowledge

- Develop learning activities that are relevant to students’ cultural experiences

- Teach new vocabulary words by making connections to students’ background knowledge

Provide explicit vocabulary instruction with guided practice and frequent opportunities to practice using new words. Educators can help ELs acquire new vocabulary by:

- Using graphic organizers to help students learn new vocabulary terms, learn the relationships between different words, and make connections with previous knowledge

- Showing pictures, diagrams, illustrations, and real objects to teach vocabulary

- Providing examples of vocabulary words to differentiate when they have several meanings

- Posting words on a word wall to learn (e.g., content-area vocabulary words, commonly used words or phrases)

Help students understand what they read by teaching them strategies to use before, during, and after reading, such as those below.

Before reading

- Preview words from the passage, using visuals whenever possible.

- Activate background knowledge by asking students to brainstorm what they already know about a topic.

During reading

- Teach students strategies to use context clues and knowledge of word parts to determine the meaning of unknown words.

- Ask students to identify the main idea for each section of text they read.

- Use literature that incorporates students’ interests.

After reading

- Ask students to summarize or retell what they read.

- Teach students to use or create visuals (e.g., charts, diagrams, timelines) to improve their understanding.

Provide ample opportunities for students to practice both their academic skills and their use of the English language while providing corrective feedback. For example, educators can:

- Allow ELs to work in pairs or in small groups

- Encourage ELs to discuss what they are learning

Create activities that require students to work in small groups. Working with peers provides academic supports and creates more opportunities to practice language skills. Cooperative learning also supports students from cultures that value collaboration over independent effort.

Something to Consider

One common misperception is that students who are learning English should not have difficulty with mathematics. Teachers often think of mathematics as being purely symbolic, a sort of universal language, and that an inability to speak English should not interfere with mathematics instruction.

Diane Torres-Velasquez explains why the belief that mathematics is a universal language is false and what teachers need to consider when teaching mathematics (time: 1:55).

Diane Torres-Velasquez, PhD

Associate Professor, Teacher Education Department

University of New Mexico

Transcript: Diane Torres-Velásquez, PhD

A lot of people think that mathematics is a universal language and that it’s something that can be taught without any difficulty for someone who’s arriving from another country and doesn’t speak our language. And there’s a couple things that I would want to caution teachers about. It’s important to consider what the profession is viewing as mathematics instruction these days, as a science of pattern and order. And mathematics is really looking at the world around us and making sense of it. And so as we’re looking at this type of perception of mathematics, then it’s really important for us to understand that it’s much more than just computation and learning to add and subtract and multiply and divide just by learning the steps. We’re looking at mathematics in a way that involves children at a much deeper level. They are active participants in their learning and their experience of mathematics. And when we look at the content of mathematics, we have five general areas, and one of them is number and operations. Another is algebra. We have geometry, measurements, data analysis, and probability. And when we’re looking at the verbs of what it is to do mathematics, we are looking at words like explore, solve, justify, develop—words that are action words and not just the directional words that we used to associate with arithmetic. Sometimes vocabulary has different meanings, and so when you just translate things for a student into English, they may have a different understanding of the word. For example, table. If you’re looking at data and you have it in a table, and you use the word table, and you’ve got a student who’s just learning English and they’ve learned table is that object that has a flat top and has four legs, then there’s going to be some initial confusion. And, obviously, that vocabulary needs to be taught.

For additional information about content discussed on this page, view the following IRIS resources. Please note that these resources are not required readings to complete this module. Links to these resources can be found in the Additional Resources tab on the References, Additional Resources, and Credits page.

English Learners with Disabilities: Supporting Young Children in the Classroom This module offers an overview of young children who are English learners. Further, it highlights the importance of maintaining children’s home language at the same time they are learning a new or second language, discusses considerations for screening and assessing these children, and identifies strategies for supporting them in inclusive preschool classrooms (est. completion time: 1.5 hours).

Teaching English Learners: Effective Instructional Practices This module helps teachers understand second language acquisition, the importance of academic English, and instructional practices that will enhance learning for English learners (est. completion time: 2 hours).

English Learners: Understanding BICS and CALP This activity helps educators gain a better understanding of the difference between basic interpersonal communication skills (BICS) and cognitive academic language proficiency (CALP) and how language differences affect classroom learning (est. completion time: 20 minutes).

English Learners: Understanding Sheltered Instruction This activity explains how English learners (ELs) might have difficulty comprehending new information and how sheltered instruction can be used to support their learning (est. completion time: 30 minutes). |