What should teachers understand to facilitate success for all students?

Page 6: Exceptionality Considerations

As educators, you will have exceptional learners—students who are gifted and talented and students with disabilities—in your classroom. Although both students who are gifted and those with disabilities have unique learning needs that often require teachers to adapt instruction, this module will focus on the latter.

As educators, you will have exceptional learners—students who are gifted and talented and students with disabilities—in your classroom. Although both students who are gifted and those with disabilities have unique learning needs that often require teachers to adapt instruction, this module will focus on the latter.

Approximately 15% of all public school students have been diagnosed with a disability. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)—the federal law that guarantees students with disabilities the right to a free appropriate public education (FAPE) in the least restrictive environment (LRE)—recognizes 13 disability categories:

gifted and talented

Term used to describe students who perform, or have the capability to perform, at higher levels than their peers in one or more domains.

disability

A variety of conditions characterized by a physical, sensory, or mental impairment that makes it more difficult to do certain things (e.g., see, hear, learn, walk) and to participate in typical daily activities (e.g., work, social activities).

free appropriate education

An Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) principle that ensures eligible students with disabilities receive individualized educations that meet their unique needs at no cost to them or their families.

least restrictive environment (LRE)

An Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) guiding principle, which requires students with disabilities to be educated alongside their peers without disabilities to the greatest extent possible.

- Autism

- Deaf-blindness

- Deafness

- Emotional disturbance

- Hearing impairment

- Intellectual disability

- Multiple disabilities

- Orthopedic impairment

- Other health impairment

- Specific learning disability

- Speech or language impairment

- Traumatic brain injury

- Visual impairment (including blindness)

Note: Federal law allows some states to serve students who are not meeting age-appropriate developmental milestones under the category of developmental delay, even though it is not one of the 13 categories in IDEA. Additionally, students who are gifted and talented are not served under IDEA.

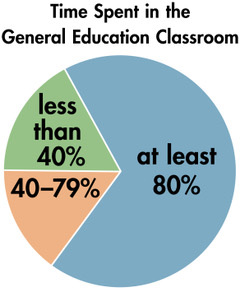

Students with disabilities are served in almost every classroom, not just special education classrooms.

- Approximately 68% of students with disabilities (ages five to 21) spend at least 80% of their time in the general education classroom.

- Another 15% spend between 40% and 79% of their time in the general education classroom.

- Only about 16% of students with disabilities spend less than 40% of their day in general education classrooms.

Source: Office of Special Education Programs (2024).

Why Exceptionalities Matter

A compelling body of research shows that students with disabilities benefit both socially and academically when they are served in general education settings. These benefits include:

- Improved academic performance

- More time spent engaged in academically challenging curricula

- Improved self-esteem and social behavior

- Development of friendships between students with and without disabilities, resulting in opportunities for companionship and increased self-concept

Example of Educator Misconception

Alexa has autism, which her teacher found out the week before school started. The teacher expected Alexa to be non-verbal and engage in self-stimulatory behaviors (e.g., rocking, hand flapping). However, this assumption was completely wrong, as Alexa actively participated in class discussions using oral speech and showed no signs of self-stimulatory behaviors. As is often the case, the teacher relied on stereotypical traits commonly associated with the student’s exceptionality label.

Although the number of exceptional learners is increasing, there are still many misconceptions about these students. For example, educators might make assumptions based on stereotypes. However, no two students with the same exceptionality exhibit the same behaviors or succeed in exactly the same ways. When educators address their own assumptions about exceptionalities, they are better positioned to create an engaging learning environment in which all students feel safe, respected, and valued.

Additionally, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and IDEA have increased the expectation that all students will participate in the general education classroom to the greatest extent possible. As such, educators are responsible for providing high-quality instruction to all students. However, students with disabilities often face challenges or barriers that inhibit or restrict their ability to access and demonstrate learning. These learning barriers can be related to:

Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA)

Federal legislation that reauthorized the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA) and replaced the No Child Left Behind Act (NCLB) in 2015; this reauthorization shifted accountability for standardized testing requirements to the states.

Did You Know?

Students who are gifted might also have a disability. For example, an individual might be identified as gifted and have autism. These students are referred to as twice exceptional. Although gifted, these students might require additional supports to succeed in the classroom.

- How information is presented (e.g., as text, in a lecture)

- The manner in which students are asked to respond (e.g., in writing, through speech)

- The characteristics of the setting (e.g., the levels of noise and lighting)

- The timing and scheduling of instruction (e.g., the time of day, the length of a given assignment)

Research Shows

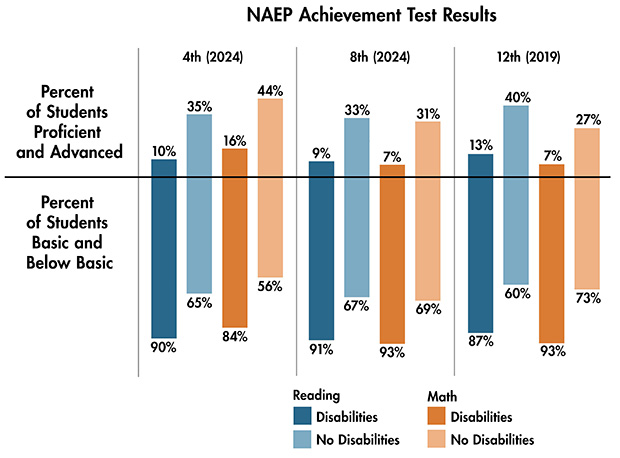

The achievement of students with disabilities often lags behind that of students without disabilities. To measure student academic achievement in the United States, the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) administers reading and mathematics achievement assessments to fourth- and eighth-grade students each year and to 12th-grade students every four years. Student performance indicates the degree to which they have acquired the knowledge and skills expected at their grade level. The results are categorized into one of four levels: Below Basic (little mastery), Basic (partial mastery), Proficient (mastery), and Advanced (beyond mastery). The 2024 reading and mathematics results for fourth and eighth grade (and 2019 results for 12th grade) are compared in the table below for students with and without disabilities.

Source: National Assessment of Education Progress. (2020, 2025). NAEP achievement test results. The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov

This bar graph illustrates the results of the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading and mathematics achievement test for fourth and eighth grade as well as the 2019 data for 12th grade. The table is divided into three sections—one for fourth-grade results, one for eighth-grade results, and one for 12th-grade results. There is a horizontal line running through all sections. The portion above the line is labeled “Students Proficient & Advanced,” while the lower is labeled “Students Basic & Below Basic.”

The test results are displayed for four categories of test takers: “Disabilities in reading,” “No Disabilities in reading,” “Disabilities in math,” and “No Disabilities in math.”

For fourth graders, 10% of students with disabilities in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 90% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in reading, 35% are Proficient & Advanced and 65% are Basic & Below Basic. For students with disabilities in math, 16% are Proficient & Advanced and 84% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in math, 44% are Proficient & Advanced and 56% are Basic & Below Basic.

For eighth graders, 9% of students with disabilities in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 91% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in reading, 33% are Proficient & Advanced and 67% are Basic & Below Basic. For students with disabilities in math, 7% are Proficient & Advanced and 93% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in math, 31% are Proficient & Advanced and 69% are Basic & Below Basic.

For 12th graders, 13% of students with disabilities in reading are Proficient & Advanced and 87% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in reading, 40% are Proficient & Advanced and 60% are Basic & Below Basic. For students with disabilities in math, 7% are Proficient & Advanced and 93% are Basic & Below Basic. For students without disabilities in math, 27% are Proficient & Advanced and 73% are Basic & Below Basic.

What Educators Can Do

Educators must take the time to understand each student holistically, considering both their strengths and areas where they might need extra support. By gaining a deeper understanding of students with disabilities, educators can design classroom environments that support them. Additionally, when a student qualifies for special education services under IDEA, a multidisciplinary team develops an individualized education program (IEP)—a written plan that outlines intensive instructional services and supports necessary to help the student learn. All educators, including general education teachers, are legally obligated to provide the services and supports outlined in each student’s IEP. Let’s look at a couple of ways to support these students in the general education classroom.

Students with disabilities should be accepted, valued, and included as integral members of the classroom. Because this doesn’t always happen organically, educators should:

- Help their students understand individual differences and that students learn, communicate, and participate in different ways

- Teach students how to work together, create opportunities for them to do so, and reinforce students when they do so successfully

- Help facilitate social opportunities in and out of the classroom (e.g., in the cafeteria, on the playground)

As mentioned above, all educators must implement the services and supports outlined in each student’s IEP. Because these are individualized to meet the unique needs of each student, they will vary from student to student. However, they often include:

Accommodation Examples

- Audiobooks (when reading is not the learning objective)

- Frequent breaks

- Extended time on tests

Accommodations—These are adaptations to educational environments, materials, or practices that allow students with disabilities to access the same instructional opportunities as their peers. They do not change what students learn but rather how they access learning. More specifically, accommodations:

- Do not change the expectations for learning

- Do not reduce the requirements of the task

- Do not change what the student is required to learn

AT Examples

- Modified scissors (low-tech)

- Audiobooks (mid-tech)

- Voice recognition software (high-tech)

Assistive technology (AT)—Although AT can be categorized as an accommodation, it typically refers to tools that facilitate the routine aspects of daily life (e.g., work, communication, mobility). These tools, which can help students access, participate in, or demonstrate learning, range from low-tech (i.e., readily available, inexpensive, and typically do not require batteries or electricity) to high-tech (i.e., typically computer-based, likely to have sophisticated features, and can be tailored to the specific needs of an individual student).

Modification Examples

- Alternate assignment

- Fewer homework questions

- Lower-level reading material

Modifications—These are also adaptations to educational environments, materials, or practices. However, unlike accommodations, modifications:

- Do change the expectations for learning

- Do reduce the requirements of the task

Ginger Blalock discusses some key considerations for students with disabilities (time: 2:34).

Ginger Blalock, PhD

Professor Emeritus, Special Education Department

University of New Mexico

Ginger Blalock, PhD

Regarding the education of students with disabilities, their individual education program includes a statement of how the student will be supported in obtaining the annual goals that the team decides is important. Every individual education program has to also include a statement about how the child will be involved in the general curriculum and actually progress in that general curriculum and also, related to LRE, how much the student will be educated and participate with students with and without disabilities. And this access to the general education curriculum is intended to be with appropriate modifications or supports or services that allow the student to be able to access the curriculum, to be able to learn from it, to be able to demonstrate what they know, and to be able to be a part of that curriculum with their peers.

The reason why this provision is so important is because historically many students with disabilities who were in the general ed. settings, classroom or school were still denied access to that general ed. curriculum. There was a tendency for educators to say, “The student cannot learn this, and therefore we’re not even going to bother. We’ll just provide them with their own curriculum, or we’ll unfortunately just kind of let them bide [their time] and not really progress.” And what this does is compel all the planners, all the folks on the team, to make sure that this student is participating as much as possible in what every other kid is learning. And so one of the greatest ways in which you see that facilitated is that now all planning that goes on for these students with disabilities must address the regular content standards and benchmarks that every child is learning at that grade level. It may mean that a student has and needs certain modifications in either the materials or the content or the sequence of presentation, the way that the instruction is delivered, or the way that he or she demonstrates knowledge or competence. So it means making changes to ensure that the kid doesn’t have a cookie-cutter approach. It means designing instruction, carrying it out, and assessing it all along the way to make sure that students are progressing and learning what is most essential for him or her to learn.

For additional information about content discussed on this page, view the following IRIS resources. Please note that these resources are not required readings to complete this module. Links to these resources can be found in the Additional Resources tab on the References, Additional Resources, and Credits page.

Accommodations: Instructional and Testing Supports for Students with Disabilities This module explores instructional and testing accommodations for students with disabilities, explains how accommodations differ from other kinds of instructional adaptations, defines the four categories of accommodations, and describes how to implement accommodations and evaluate their effectiveness for individual students (est. completion time: 2 hours).

Assistive Technology: An Overview This module offers an overview of assistive technology (AT) with a focus on students with high-incidence disabilities such as learning disabilities and ADHD. It explores the consideration process, implementation, and evaluation of AT for these students (est. completion time: 2.5 hours). |