What should teachers understand to facilitate success for all students?

Page 7: Socioeconomic Considerations

Just as students will have varied cultural backgrounds, speak many languages, and have different learning needs, they will also come from various socioeconomic levels. A family’s socioeconomic level or status (SES) is defined by the combination of income, education, and occupation of household members and is typically categorized as either high, middle, or low. Households that are usually considered low SES make less than two-thirds of the median income for the area where they reside, and high-SES households make more than double the median income. There are millions of students living in households categorized as low SES.

Just as students will have varied cultural backgrounds, speak many languages, and have different learning needs, they will also come from various socioeconomic levels. A family’s socioeconomic level or status (SES) is defined by the combination of income, education, and occupation of household members and is typically categorized as either high, middle, or low. Households that are usually considered low SES make less than two-thirds of the median income for the area where they reside, and high-SES households make more than double the median income. There are millions of students living in households categorized as low SES.

Why SES Matters

For Your Information

One in six school-age children live in poverty, and over half of all public school students are eligible for free and reduced lunch.

One of the most influential factors in a student’s academic performance is the family’s SES. Often, students living in low-SES households encounter daily challenges that can impact their learning. Although these experiences vary from family to family, many students from low-SES households will encounter at least some of these. The boxes below offer examples of challenges students from low-SES households might experience in their daily lives and the resulting impact that educators might observe in the classroom.

Potential Challenges

Students might experience:

- Not having basic needs (e.g., food, housing, clothing) met

- Inadequate healthcare

- Transiency or homelessness

- Poor nutrition

- Less supervision at home

- Fewer hours of sleep

- Limited access to transportation

- Delayed language development

- More responsibilities at home (e.g., childcare, cooking meals)

- Few educational resources at home (e.g., books, computers)

- Reduced opportunities to participate in extracurricular school or community activities

- Read to less frequently at home

- Less help with homework

- Less access to enrichment (e.g., tutors, museums)

Impact on Students

Students might have difficulty:

- Staying awake

- Concentrating

- Remaining engaged

- Attending school regularly

- Being on time to school

- Communicating with others

- Completing or turning in homework

- Bringing materials to class

- Performing on grade level

- Staying in school and graduating

Note: Because caregivers often work multiple jobs and longer hours, they have less time to spend with their children on academics and are less likely to be involved in school events and meetings.

Research Shows

- By the time students from low-SES households reach preschool, the chronic stress of poverty has already slowed their brain growth and hindered their cognitive development and ability to regulate emotions. This negative effect on brain development may account for up to 20% of the achievement gap between students from low- and high-SES households.

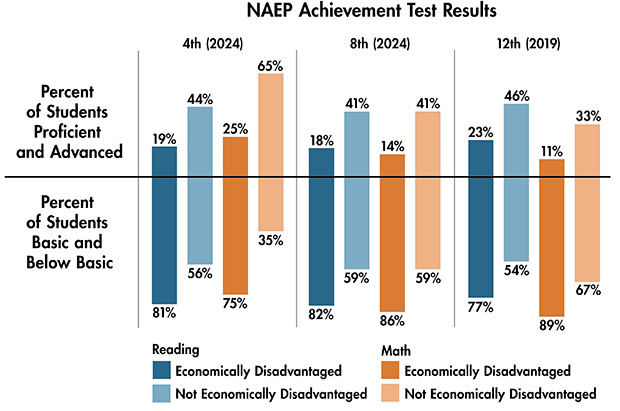

(Hair et al., 2015) - The achievement of students from low-SES households often lags behind that of students from middle- and high-SES households. To measure student academic achievement in the United States, the National Assessment of Education Progress (NAEP) administers reading and mathematics achievement assessments to fourth- and eighth-grade students each year and to 12th-grade students every four years. Student performance indicates the degree to which they have acquired the knowledge and skills expected at their grade level. The results are categorized into one of four levels: Below Basic (little mastery), Basic (partial mastery), Proficient (mastery), and Advanced (beyond mastery). The 2024 reading and mathematics results for fourth and eighth grade were compared in the table below for students categorized as economically disadvantaged and those who were not. The 2019 results for 12th grade reflect students who were eligible for the National School Lunch Program (NSLP) compared to students who were not eligible.

Note: Fourth- and eighth-grade students were considered economically disadvantaged if they participated in supplemental programs for low-income families (e.g., Community Eligibility Provision [CEP], Medicaid), were classified as economically disadvantaged based on a family household income survey, qualified for free meals based on household income, or attended a CEP school where all students are considered economically disadvantaged despite individual household income levels. The data for 12th-grade students reflects those who were eligible for NSLP. Additionally, due to insufficient information, some students were not categorized and thus are not reflected in the graph.

Source: National Assessment of Education Progress. (2020, 2025). NAEP achievement test results. The Nation’s Report Card. https://www.nationsreportcard.gov

This bar graph illustrates the results of the 2024 National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) reading and mathematics achievement test for fourth and eighth grade as well as the 2019 data for 12th grade. The table is divided into three sections—one for fourth-grade results, one for eighth-grade results, and one for 12th-grade results. There is a horizontal line running through all sections. The portion above the line is labeled “Students Proficient & Advanced,” while the lower is labeled “Students Basic & Below Basic.”

The test results are displayed for four categories of test takers: “Economically Disadvantaged in reading,” “Not Economically Disadvantaged in reading,” “Economically Disadvantaged in math,” and “Not Economically Disadvantaged in math.”

For fourth graders, 19% of students who are economically disadvantaged are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 81% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 44% are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 56% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are economically disadvantaged, 25% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 75% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 65% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 35% are Basic & Below Basic.

For eighth graders, 18% of students who are economically disadvantaged are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 82% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 41% are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 59% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are economically disadvantaged, 14% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 86% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 41% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 59% are Basic & Below Basic.

For 12th graders, 23% of students who are economically disadvantaged are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 77% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 46% are Proficient & Advanced in reading and 54% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are economically disadvantaged, 11% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 89% are Basic & Below Basic. For students who are not economically disadvantaged, 33% are Proficient & Advanced in math and 67% are Basic & Below Basic.

Because students living in low-SES households often must take on adult responsibilities (e.g., caring for siblings, cooking dinner), they might be more independent than their peers from middle- and high-SES households. This independent mindset can cause tension in the classroom and can affect how they behave and communicate with authority figures. Listen as Lanette Waddell, former Director of Teaching and Learning in Urban Schools (TLUS), discusses this in more detail (time: 1:29).

Lanette Waddell, PhD

Former Assistant Professor, Former TLUS Director

Vanderbilt University

Transcript: Lanette Waddell, PhD

Poor students, particularly, grow up in a natural growth way. Their parents tend to be directive. They tend to tell them things to do. You know: “Go brush your teeth,” “Go set the table,” “Go wash the dishes.” It’s not a conversation. It’s mostly, let’s do this, let’s do that, let’s move forward. And students follow those directions because it’s their parents. But they also get a lot of free time where their free time is not structured. It’s open. They can do what they want. They make up their own games. They play. They do whatever they want. They also carry a lot of responsibility. They have to get up, make their own breakfast, wash their clothes, clean their house, take care of their siblings, get to school by themselves. They do a lot of independent work, so they come to school with a much more independent mindset than you would see with maybe students who have mother at home and a father who works, or where there’s money so that there’s someone there taking care of them all the time. But it can cause some tension in school because when you go to school, then you’re told what to do. You’re told when to do this, and when you’re going to do that. You’re not independent in the way that you are at home, in your own personal decisions. When you think about students who are independent and are able to do what they want to do when they’re at home, and they are able to take care of themselves, and they bring that independence into school, you have to be able to understand that but also let them know that we are in school with others and we have to follow certain procedures so that everyone is safe and everyone is comfortable and content here so that we can all learn.

To get a better idea of what the impact of living in a low-SES household might look like in the classroom, consider the story of Elijah, a 12-year-old sixth grader. Elijah often falls asleep in class and does not turn in his homework on time. Lately, Elijah seems confused about which bus to ride home. His teacher is concerned about Elijah and is looking forward to discussing her concerns with his parents. When Elijah’s parents miss their scheduled parent/teacher conference, though, she assumes that education is not a priority in his family. After several attempts to reach Elijah’s parents, his teacher finally connects with his mom. Apologetically, Elijah’s mother explains that she was unable to attend the conference because she had to work overtime. She has two part-time jobs, and Elijah’s dad works the evening shift. Because of this, Elijah takes care of his younger siblings, including cooking their dinner, bathing them, and putting them to bed. In addition, Elijah and his family have had to move several times recently, which explains why Elijah is sometimes uncertain about which bus to ride home.

To get a better idea of what the impact of living in a low-SES household might look like in the classroom, consider the story of Elijah, a 12-year-old sixth grader. Elijah often falls asleep in class and does not turn in his homework on time. Lately, Elijah seems confused about which bus to ride home. His teacher is concerned about Elijah and is looking forward to discussing her concerns with his parents. When Elijah’s parents miss their scheduled parent/teacher conference, though, she assumes that education is not a priority in his family. After several attempts to reach Elijah’s parents, his teacher finally connects with his mom. Apologetically, Elijah’s mother explains that she was unable to attend the conference because she had to work overtime. She has two part-time jobs, and Elijah’s dad works the evening shift. Because of this, Elijah takes care of his younger siblings, including cooking their dinner, bathing them, and putting them to bed. In addition, Elijah and his family have had to move several times recently, which explains why Elijah is sometimes uncertain about which bus to ride home.

Schools are often based around middle-class norms and values. Elijah’s teacher assumed that his parents were home in the evenings and never considered that Elijah might have so many responsibilities at such a young age, which contributed to inadequate sleep and incomplete homework. Like Elijah, students from low-SES backgrounds might display behaviors that interfere with their ability to succeed in school. As Elijah’s teacher did, school personnel sometimes assume that the student in question is unmotivated, lazy, or has an unsupportive family. Alternatively, they might think that the student has a disability that affects their learning or behavior.

What Teachers Can Do

To more effectively teach students from low-SES households, educators should consider the impact that outside factors can have on their students’ academic performance. Although these impacts can be tremendous, there are steps educators can take to mitigate these negative effects, such as those below. However, keep in mind that not all students from low-SES households face the same challenges or behave in the same manner.

Teachers who form strong relationships with their students are better able to recognize students’ individual needs. Although educators might be able to address some of these needs, they are not alone in providing resources and support for students from low-SES households. Other members of the school who have specific expertise (e.g. school counselor, social worker, school nurse, administrator) can help identify a student’s basic needs and link them to resources and services. Many of these can be provided by the school (e.g., school supplies, breakfast and lunch, food bank). In other cases, school personnel can connect students and families to community agencies and groups that offer specialized supports or services (e.g., dental services, vision and hearing screenings). In addition to these school-based supports, educators can also help meet the needs of these students by:

- Building strong, positive relationships with students to gain a better understanding of their circumstances and needs

- Scheduling time for them to access resources (e.g., library, computer, quiet places to study, time) and complete assignments

- Offering help with instructional needs

These students could have low self-esteem and might not receive a lot of positive reinforcement; therefore, educators need to provide positive feedback and establish classroom practices that increase student motivation and engagement. Educators can do this by:

- Providing extrinsic rewards (e.g., pencils, stickers, extra computer time)

x

extrinsic rewards

Reward outside of an individual (e.g., stickers, points, praise) that encourages desired behaviors.

- Providing more frequent praise (note: does not have to be related to a specific task)

- Incorporating students’ strengths and interests into instruction

- Including practical applications to help students understand how the content is related to their lives

- Establishing high expectations and ensuring all students have equal access to rigorous content

Typically, families living in low-SES households are less engaged at school due to many factors (e.g., work conflicts, lack of transportation, negative personal school experiences). Additionally, these families may feel disrespected, uncomfortable, or as if they have little to contribute to their child’s school. However, decades of research have shown that when families are involved in their child’s education, students show improvement in academic achievement, attendance, behavior, social-emotional skills, and graduation rates. Educators can facilitate family engagement by:

- Finding ways to reach families, particularly if they do not have a phone, do not speak English, or cannot read

- Scheduling conferences at convenient times for parents

- Providing food and childcare while parent/teacher conferences are being held

- Meeting for conferences at community centers or other locations to increase attendance among families without transportation

- Emphasizing the student’s strengths when having discussions with parents

- Encouraging family input and ensuring parents know their perspectives are valued

- Recognizing the family could have different priorities for the student

Because students from low-SES backgrounds might display delayed language skills, educators can use evidence-based practices to help improve students’ language skills. This can mediate some of the negative effects poverty can have on students’ academic performance. Listen as Dolores Battle discusses the importance of language for developing literacy and what teachers can do to support students’ learning (time: 2:14).

Dolores Battle, PhD

Professor Emeritus Buffalo State College

Transcript: Dolores Battle, PhD

When the child comes in and this is his first exposure to school, one of the main considerations for the teacher is, What has this child’s exposure been to preliteracy? What kind of language goes on in the home? There’s a lot of studies that show that the lower the income, the lower the education of the parents, the less language the children are exposed to at home—less words, a smaller vocabulary, shorter sentences, less direct questioning, all of the things that contribute to a solid foundation for developing literacy in school. And we don’t want to assume that because the family is low income that they all have come into school with poor skills. The main point is to take a look at what the child brings to school, their background. It’s all about language. It’s knowing how to listen, how to understand the vocabulary, how to ask questions. Many children at home, they’re not allowed to ask questions, particularly for information, from their parents. They’re not allowed to initiate conversations with adults. And here they are in an interaction where they’re with a teacher who is an adult, and a strange adult as it is. So in those early years, it’s all about developing language skills, comprehension skills, and expression skills. So teachers need to be aware that you need to have that very firm foundation in language as a prerequisite for literacy. And if you fail to build that, the child will be forever behind. They need to do a lot of reading, developing vocabulary, making sure the children really understand what’s being read. Not just reading the book once, but sometimes it takes four and five times to read the book. Much as children do in a family where the book is read, the same book, every day for a month, for two months, because that becomes the child’s favorite book. All too often, classroom teachers think that once they’ve read the story, then that’s enough. But if you’re going to develop a basis of literacy, then it has to follow that same rule, where children get the information. They learn to ask questions about it. They learn to predict what’s going to happen, all of which happens in homes where literacy is developed early. That same process has to follow if children who are entering into school who don’t have that foundation.

Activity

Three weeks into the school year, Mrs. Arellano, a tenth-grade English teacher in an urban high school, is frustrated that many of her students are still without the required materials, which cost less than $10.

Because of this, her lessons are frequently disrupted as students try to borrow materials from their classmates. Many of the students claim that they don’t have the money to buy the items. Although she knows that many of them qualify for free or reduced-price lunches, Mrs. Arellano wonders how her students can afford expensive clothing items and electronic devices, and she doesn’t understand how their families justify buying these expensive items instead of basic school supplies.

What are your perceptions about the students in the scenario? How would you handle the fact that the students don’t have the required materials?

In the first audio, Richard Milner provides some insights into this situation. In the second, he discusses how teachers might address similar circumstances.

H. Richard Milner IV, PhD

Associate Professor, Department of Teaching and Learning

Vanderbilt University

Transcript: H. Richard Milner IV, PhD (Insights)

I think this is a very important scenario, and it speaks to what many teachers experience. One of the things that’s critical for students to participate in the educational experiences, to participate in interactions with their friends and classmates, is for them to feel good about who they are. And so sometimes that means that students might feel like they have to have the latest fashion, the newest tennis shoes, or the latest polo shirt, or whatever it happens to be. But what’s important to remember is that students are doing that because they want to feel good about themselves. I’ve studied suburban schools. I’ve done work in rural areas. I’ve done a lot of my work in urban spaces. And what we find is that students are grappling with identity issues in all of those spaces. And the ways in which students respond to pressures that they are grappling with—whether it be academic, whether it be in a relationship with a friend or a classmate—they respond to those pressures in different ways.

And so some students might go and do drugs. Some students might stop going to class. Other students might purchase materials—technology, clothes, shoes—that we might see as marginal to what matters in terms of their development. The big piece is that students are grappling with very difficult situations in different contexts, and students’ or parents’ decision to have their children purchase clothing items or shoes is just one form of working on that identity piece.

Transcript: H. Richard Milner IV, PhD (Addressing the issue)

Some students are more school dependent than are other students, and so the school really has to play the vital role of being responsive to the economic and the educational needs of students. On a structural level, this goes beyond the teacher’s classroom. I think the school should be responsible for making sure students have what they need to be successful. The second thing is, if students understand the necessity for them to be actively involved in what’s happening in the classroom and that it’s necessary for them to spend money on resources to be successful, then that’s part of the work that I think needs to take place in an explicit way with the teacher helping students understand why she is pushing them to spend resources on school-related materials rather than on shoes or clothing or whatever that happens to be. But in order for those kinds of conversations to happen, the teacher has to develop solid and sustainable relationships with those students. If the teacher has not developed solid relationships such that she can say, “Listen, guys, I want you to be successful. I care about you, and I really wish you would put your emphasis on your academic development rather than worrying about how you look or the kinds of shoes you wear” and those kinds of things.

Now, in order for her to do that, that means she’s going to have to counter so many things the students have come to believe about themselves and really engaging in conversations and listening to students in terms of why they choose to spend money on clothing or shoes rather than on resources for the classroom. And I think that’s done also in consultation with parents as well. The ability of this teacher to talk with and empathize with the parents is also important so that the teacher and the parents can partner together around what is important. I think the thing that would do more harm than good is for the teacher to go in in a judgmental way with parents about why the parents are making the decisions they are making. So it really has to be a partnership, you know: “I care about your child. I want him or her to be successful. Here’s what you can do to help me with that. Now, I’m open as a teacher to hear what things I can do to complement and supplement what’s necessary for your child to be successful as well.”

For additional information about content discussed on this page, view the following IRIS resources. Please note that these resources are not required readings to complete this module. Links to these resources can be found in the Additional Resources tab on the References, Additional Resources, and Credits page.

Family Engagement: Collaborating with Families of Students with Disabilities This module—a revision of Collaborating with Families, which was originally developed in cooperation with the PACER Center—addresses the importance of engaging the families of students with disabilities in their child’s education. It highlights some of the key factors that affect these families and outlines some practical ways to build relationships and create opportunities for involvement (est. completion time: 1 hour). |