How can educators engage these families?

Page 5: Build Positive Relationships

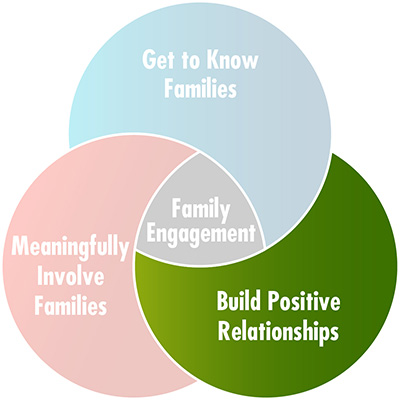

Recall that to successfully achieve family engagement, educators must get to know, build positive relationships with, and meaningfully involve families. Establishing positive relationships creates an atmosphere conducive to family involvement. This is vital in improving outcomes for students, families, and the school, as well as in the greater community. Let’s look at a number of actions educators can take to accomplish this.

Recall that to successfully achieve family engagement, educators must get to know, build positive relationships with, and meaningfully involve families. Establishing positive relationships creates an atmosphere conducive to family involvement. This is vital in improving outcomes for students, families, and the school, as well as in the greater community. Let’s look at a number of actions educators can take to accomplish this.

Creating an accepting and supportive environment is the first step in welcoming families. When families enter a school building, they should feel valued and included. This is especially true for the families of children with disabilities, who may already be grappling with a number of stressors. But a welcoming school environment is more than just a friendly front office staff. The interactions of everyone in the school—administrators, teachers, support staff, students, and visitors—should be caring and supportive. Educators can welcome families by creating opportunities for parents to make positive connections within the school. They can do this by:

- Scheduling events at times convenient for parents

- Hosting special events that foster connections (e.g., Meet the Teacher Night, Coffee and Conversations with the Principal, School Tours, Family Fun Night)

- Hosting parent nights that address parent concerns (e.g., Internet Safety for Children, Free Adult English Classes, Your Rights as a Parent of a Child with a Disability)

- Offering volunteer opportunities for parents (e.g., read to a class, guest speaker, car rider line volunteer)

- Holding a multicultural night to celebrate the different cultures represented in the school

- Providing a translator when necessary and making information available in families’ home language

Listen to Anne Henderson emphasize the importance of welcoming and involving families in an effort to help all children to learn and succeed (time: 2:44).

Anne T. Henderson

Senior Consultant, Community Involvement Program

Annenberg Institute for School Reform

Washington, DC

Transcript: Anne T. Henderson

I do want to emphasize how important it is to make sure everybody in the school community feels welcome and involved. I sometimes worry when we’re sitting down and looking at school data and we say, well, these certain kids aren’t doing well. We really have to raise their achievement, so let’s work with their parents when the school as a whole isn’t working with parents well. We have to create what I would call a family-friendly school that really is open and accessible to families, that reaches out to them, all families, and create a general climate of partnership in the school. And then when we reach out to families whose children are lagging academically or emotionally or behaviorally or whatever it is, you’re going to have the groundwork all laid to make the steps to have that extra collaboration that’s so needed. It’s the school that sets that tone. If the school is really centered on children and children doing well then they run much less of a risk of parents being advocates narrowly just for their own children. And everybody in the school community’s going to be more mindful of what’s happening for all children in the school.

The schools need to make sure that families of children with disabilities feel accepted and welcome and not blamed in any way for their children’s disability. I think it’s very important for schools, school staff, teachers, the principal, counselors, everyone working in a school community understands that it’s their role to make sure that every family whose child has a disability gets strong signals of support, of acceptance, of encouragement, of help, of a shoulder to lean on. I think that that’s vitally important. That’s, like, the first line of approach with families. And it’s very important to build personal relationships with families. It’s nice to be polite and have a website and a phone hotline, and a friendly welcoming-looking building, but we have to go beyond that and make sure that every single family feels welcome and connected to the school and to different people in the school.

Often parents of children with disabilities are struck by how differently their children are described during conversations and conferences with educators. When educators talk about a child who doesn’t have a disability or an identified need, they often focus on that child’s abilities, talents, and progress. Conversely, when they speak of a child with a disability, educators tend to focus on deficits, challenges, or areas that need to be addressed. It is important for educators to recognize that the child has strengths and to communicate that to the families.

In addition to emphasizing the child’s strengths, educators should acknowledge the strengths that families possess (e.g., knowledge about the child’s disability, experience using successful strategies with the child at home). Doing so will establish the basis for a more meaningful partnership between schools and families.

Listen as Aubri Girardeau discusses some of the ways educators have acknowledged the strengths of her child and her family (time: 1:12).

Aubri Girardeau

Mother of a child with autism

and specific learning disabilities

Transcript: Aubri Girardeau

They have been amazing. When she does something new or unexpected, they are so excited. Like, we had one teacher last year that encouraged her to give a book report in front of her peers, and she videoed it and was so proud of her and couldn’t wait to share it with me. And this year it was like a light bulb moment in math. And the teacher was so excited, she couldn’t wait to just call me and say you will not believe what your daughter did today. It was amazing. We were so proud. It makes me feel like they’re as invested in her as we are.

They love to share how much she loves talking about her brother. They always find things to compliment. They’ll say, well, it’s obvious that you’ve taught Claire this at home. We appreciate it so much. It makes our job so much easier. They do definitely seem to notice things. They’ll say, well, she was so excited about the trip that you guys took. I’m so glad ya’ll had fun. They always acknowledged things like that for us. It definitely makes me feel more respected and accepted as well. That they truly see us when they see our family makeup and we know they love our daughter, they truly seem invested in everything about her, which makes us more trusting of them.

No meaningful family engagement can be established until relationships of trust and respect are established between home and school.

Some families might feel hesitant to visit the school because they do not trust educators. This is often the result of families not feeling respected by educators or of past experiences with schools. To begin building respectful and trusting relationships, educators should:

- Be available and responsive — This can be accomplished by simple acts, such as sharing contact information and actively listening to parental concerns. Additionally, educators returning phone or email messages in a timely manner, and following through with what they say they will do also helps to build trust.

- Maintain confidentiality — Educators must be mindful to not share any personal or sensitive information about the family with others except on a need-to-know basis and even then only with the family’s express permission.

- Recognize that families may have different perspectives — These perspectives may be influenced by such factors as background experiences, culture, and educational levels. For example, some people view disability negatively as a condition to “fix,” while others adopt a more positive perspective and think of disability as a characteristic of a person and a natural part of life. Parents will also have different perspectives on school involvement. Some parents will wish to take on the role of active partners with the school, whereas other parents might tend to view educators or schools as experts and assume a more hands-off approach.

For Your Information

Students with disabilities represent different races, ethnicities, cultures, and socioeconomic backgrounds. They also speak many different languages. Educators should not make generalizations about these families. Rather, they should develop an awareness of the desires of each family. The best source of information about the family is the family members themselves. To develop this awareness, educators can:

- Understand how people of different ethnicities and cultures view disability itself (e.g., as a stigma, particularly as pertains to mental illnesses or developmental disabilities; as a gift or blessing). Even if they do not agree, it is essential that educators respect those views to build effective working relationships.

- Learn about the individual family’s values and their expectations and priorities for their child’s educational needs.

- Recognize where there are differences in perspectives regarding the educational system and services.

- Discuss with the family how best to work together.

- Find ways to accommodate family involvement (e.g., transportation, translators).

- Communicate with the family in ways that are respectful of their preferences.

For more information on working with these families view the following information briefs.

Listen to Anne Henderson talk about some other factors that help build trust and foster improved relationships between schools and families (time: 1:13).

Anne T. Henderson

Senior Consultant, Community Involvement Program

Annenberg Institute for School Reform

Washington, DC

Transcript: Anne T. Henderson

Trust tends to exist in a place where people respect one another, when they treat each other with respect and courtesy. That’s so important: to treat everybody in the school community, and that’s students, families, support staff, custodians, teachers, aides, everybody treated with respect and personal regard. Schools with high trust levels tend to feel that the people who work there and the families who send their children there have integrity. And that means they do what they say they’re gonna do. They follow up. They don’t bad mouth you behind your back. And I think that’s very important because educators tend to use labels a lot. And children and families get labeled, and the labels are often not positive. The last element in the trust formula is personal regard. And that means feeling that the people around you will go to bat for you, will go out of their way to help you. Nothing builds trust like that.

Generally speaking, parents are the one constant influence and presence in their child’s life. For many children with disabilities, parents are actively involved in their lives well into adulthood, whereas teachers influence their lives for only one or two school years. When educators recognize parents as the ultimate decision-makers on behalf of their child and view learning as a shared responsibility with families, the child’s educational needs are more likely to be met.

Generally speaking, parents are the one constant influence and presence in their child’s life. For many children with disabilities, parents are actively involved in their lives well into adulthood, whereas teachers influence their lives for only one or two school years. When educators recognize parents as the ultimate decision-makers on behalf of their child and view learning as a shared responsibility with families, the child’s educational needs are more likely to be met.

To respect parents as ultimate-decision makers, educators need to recognize them as advocates for their child (at least until the child reaches the age of majority). For example, when parents are equal and valued members of the individualized education program (IEP) team, they can:

age of majority

glossary

- Offer valuable insight about their children’s skills and abilities, information that educators can use to identify students’ strengths and areas of need and provide them with quality services

- Promote the continuity of services, interventions, and practices

- Between home and school — Parents often serve as the bridge between the school and the community because students with disabilities often require assistance in areas other than academics (e.g., healthcare needs, behavioral therapy, or transitioning from secondary school to employment).

- From year to year — Parents are often the only people (other than the students themselves) who remain part of their child’s IEP team throughout the school years.

Educators can forge increasingly positive relationships by remembering to focus on what they and the parents have in common—a desire to see the child succeed in school. Each encounter with a parent is an opportunity to build the relationship. On occasion, a teacher may not understand or agree with a parent’s decision about how to best address the needs of the child. It might be that the parent’s decision is based on factors, such as past experiences, of which the teacher is unaware. Or it might be that the family doesn’t understand the processes related to the provision of special education services and supports. In such instances, communication is key.

Let’s listen to Aubri Girardeau talk about her experience as a decision-maker and the need for better communication. Then listen to Anne Henderson talk about parents as decision makers.

Aubri Girardeau

Mother of a child with autism

and specific learning disabilities

(time: 1:24)

Anne T. Henderson

Senior Consultant, Community Involvement Program

Annenberg Institute for School Reform

Washington, DC

(time: 1:00)

Transcript: Aubri Girardeau

I guess I am kind of an overseer because no decisions can be made without my approval. And I appreciate that, but it can be intimidating at times. When I’m expected to help with her goals, even though I don’t really have any formal training in developing goals. And sometimes in IEP meetings, I kind of feel more like an interloper. Not because of how they’re making me feel, but they may be using terminology I’m not familiar with, discussing educational settings that I have no knowledge of. It can be a little bit frustrating. But I do see myself as a partner with them.

I’ve always loved my daughter’s team, and we work very well together. But there was some question last year about whether or not it was time to change her setting, and when they called the meeting they presented their ideas and the ideas took me so off guard. I felt blindsided because for some reason in our system, there’s really nowhere you can go to get a breakdown of what this setting is, and this is what this setting is, and this is what this one is. And these are the children that would be here versus here versus here. The first time you hear the terms to describe the settings, very possibly you’re in the meeting where you’re discussing if that’s the best fit for your child. I don’t really know what I would suggest, but just a way to make parents of special education children aware that these are all the various settings we have. These are the schools that house them. These are the types of children that seem appropriate. I feel like maybe communication could be better.

Transcript: Anne T. Henderson

Parents as decision makers can be everything from working with the IEP team to decide what’s the best placement for your child, to sitting on the school council, if there is one, or school committees or the school improvement team and the school parent organization to make decisions about what needs to be done to address different problems and issues and concerns in the school community. It could be everything from how do we have more access to gifted and talented programs for kids with disabilities or kids from low income or families of color? How do we break those barriers? How do we improve the achievement gap? How do we improve science achievement for girls? Or reduce behavioral issues for boys? You know, all the things that come up in a school community, parents need to be part of the problem-solving process, and that means making decisions.