How can school administrators support implementation of high-quality IEPs?

Page 6: Monitoring IEP Fidelity and Student Progress

Procedural Requirements Guidelines

Involve parents in the IEP process

Involve parents in the IEP process- Implement the special education services as written in the IEP

- Adhere to required timelines

Substantive Requirements Guideline

- Document how, and how frequently, a student’s progress toward her IEP goals will be measured and reported

As we covered on a previous page, to ensure the greatest likelihood that the student will make appropriate progress, any services and supports outlined in the IEP must be implemented correctly. To facilitate this outcome, the school administrator needs to confirm that data is being collected on both the fidelity of IEP implementation as well as on the student’s progress toward meeting her goals. By utilizing data-based decision-making processes, the school will be better prepared to respond quickly and efficiently if either fidelity is low or the student is not making appropriate progress.

fidelity of IEP implementation

The extent to which the services and supports outlined in a student’s individualized education program are correctly and fully implemented.

Collect Data on Fidelity of Implementation

Once the IEP has been created and implemented, school administrators need to have procedures in place to monitor whether the IEP is being implemented as planned. Failure to do so may be a denial of FAPE, even in instances in which the IEP is otherwise procedurally and substantively sound. School professionals must understand that failure to carry out the responsibilities and services outlined in the IEP puts the district, and potentially themselves, at legal risk. Below are some guiding questions and information for school administrators to consider when developing procedures to monitor whether the IEP is being implemented with fidelity.

|

Are school personnel implementing the services and supports described in the IEP? |

|

It is the school administrator’s responsibility to make sure all personnel responsible for providing services to the student are aware of their responsibilities. To facilitate this process, the school administrator needs to:

|

|

Are school personnel implementing each service and support in the IEP with the correct frequency and duration? In the correct setting? |

|

Because altering frequency, duration, or setting might severely impact the efficacy of a service or support, it’s important that school administrators verify these aspects of implementation. Failure to do so might result in a denial of FAPE. School administrators might find it helpful to use a checklist (such as the one below) that describes the:

|

|

How often will fidelity data be reviewed and analyzed? |

|

It is helpful to review fidelity data within six weeks to verify whether services and supports documented in the IEP are being implemented with fidelity. In instances of low fidelity, school personnel should identify problem areas and develop procedures to address them. Periodic, unannounced spot checks throughout the school year have proven quite effective for maintaining high fidelity levels. |

|

How will low fidelity of implementation be addressed? |

|

School administrators need to have a decision-making system in place to determine required actions for when services and supports are not being implemented with fidelity. These actions should address the reason the service provider is not implementing with fidelity, such as a lack of understanding, resources, or training. The school administrator’s response to low fidelity should be supportive and provide educators with the assistance they need to implement the IEP as intended. For example, it may be sufficient to offer feedback and conduct further observations soon afterward (e.g., a week later), or it may be necessary for the person demonstrating low fidelity to participate in other activities, such as a booster training session or mentoring. If there are any concerns with the IEP and its implementation, parents need to be informed. |

In the interview below, David Bateman discusses the importance of monitoring the fidelity of IEP implementation and suggests one way to monitor IEP fidelity. Next, Breanne Venios describes the processes that her school uses to monitor and support IEP fidelity. In particular, she discusses the importance of the learning support teacher (i.e., special education teacher) in this process.

David Bateman, PhD

Professor, Department of Educational Leadership

and Special Education

Shippensburg University

(time: 3:08)

Transcript: David Bateman, PhD

Administrators need to monitor IEP fidelity, because if there is a discipline action the first thing we often look at is the IEP being implemented as it’s being written? If there is a complaint from a parent, we look at is the IEP being implemented as it’s being written? If there is a need to think about change in services because the child may need more intensive services, we look at is the IEP being implemented as it was written? So IEP fidelity. We need to remind administrators and teachers that once the IEP meeting is over, that’s just the beginning. We think about getting the signatures on the IEP as the most important part, but actually the most important part is actually the implementation. It’s very similar to, for lack of a better term, campaigns and someone’s running for president. Yeah, they spend an enormous amount of time campaigning, but the big thing is actually the running of the program that they’ve campaigned for afterwards. Similar to an IEP, it’s implementing the program afterwards and making changes as you go through.

The team has agreed on what the goals and what the program is for a child. The team has also agreed on how much time that it is going to take for the child to receive these special education services, and we need to at least give it opportune time to be implemented. And if there are changes that need to be made then we make the changes later, but we need to see if we can implement what the team has agreed to. And if it can’t be then we reconvene the team, and we make changes as a result of what we’ve observed. But we don’t have anything to go on unless we’ve at least tried this. So the fidelity of the implementation of the IEP is actually one of the more important parts, because everything legally then will come back to it. Did you implement how many times a child was supposed to receive speech services? Did you actually work on the goals that were listed in the IEP? Did you provide the accommodations in the general education classroom that were listed there? These are questions that will be part of what’s going on. I’m a former due process hearing officer, and I witnessed many times attorneys questioning teachers and administrators about the implementation of the IEP. Yeah, you had a good IEP, but did you actually implement it? And if you have a great IEP and you don’t implement it, that’s not defensible.

Principals should monitor the implementation of an IEP. This might be delegated to a case manager. What I recommend for principals is that they periodically meet with their special education staff. Increasingly, I’m seeing districts that are going on a nine-week schedule with four nine-week marking periods. About halfway through the first marking period after the IEP is being implemented, just sit down with the teachers for five, ten minutes. We’re not talking long. Just pull a few select IEPs and ask the teacher is this happening? If it’s not happening, and if it’s not then what can we do to make sure it does happen? It’s a quick conversation, and it’s not done in a punitive fashion. It’s done just to make sure that we’re implementing what’s going on, because in the end it’s the principals who this comes back on. As the leader of the building, they’re the ones who need to make sure that all the programs within their building are being implemented as they’re supposed to be.

Transcript: Breanne Venios

The processes that our school uses to monitor IEP fidelity are we first-and-foremost have the learning-support teacher on the front lines. They are the ones that see their student the most. They are in different classrooms with their students and with the teachers. If there is a concern, they are the ones that will probably see it first. They might bring that to me, and then I would address the fidelity that way. If we have concerns with the students making progress, we ask ourselves are we following the IEP as we need to be? We do intervention checklists, which often start with are we following the students’ IEPs? Are we giving them extra time when needed? Are we putting them in a small group for testing? Are we eliminating an answer choice? So we have our own checklist to make sure that we’re following those. We also have what we call student-support meetings, which means our director of special ed, the principal, and our school psychologists get together, and our students that have IEPs are discussed, and we make sure that they’re making that progress, and if they’re not then we ourselves put in place things with the teachers or we follow up the next month to see if any changes need to be made or we need to have a team meeting and see where we’re going. So there’s lots of different ways that we monitor the fidelity of the IEP. But, again, it goes back to that team effort, and everybody plays their part, and we all have to be held accountable for that.

There are multiple ways that teachers could improve their fidelity of following the IEP. I’ve had the learning-support teachers sit down with the regular ed teacher and explain some things that they can do, show them how to make accommodations on the tests or on the worksheets or whatever it is. I’ve also had learning-support teachers give them some tips and strategies on how to know when to do those things. I’ve sat down with them. I’ve also had some teachers observe other teachers who do a really good job with that. So if it’s something behavioral or classroom management–if it’s, like, a student with emotional support–how to monitor those de-escalation techniques and observe those so that they can start using those. So we do a couple of different things. I’ve given some books to teachers for them to read specifically, if it’s something that they’re really struggling with to kind of do their own professional learning. So we’ll talk about that book together, so maybe like a book study. So there’s lots of different ways. I’ve even had a teacher go to a training with something that was concerning, and I went with that teacher. I try to do it as a team with them, and if I can’t do it as a team I often try to bring in a colleague so that they can also be part of a team, because I think we learn from each other, and it’s a little less threatening that way if it’s a team effort.

Collect Data on Student Progress

Recall that IDEA regulations require the IEP team to document how they will measure the student’s progress toward meeting her IEP goals. They also need to document how frequently they will monitor this progress.

For Your Information

Monitoring progress and progress monitoring are two terms that are often used interchangeably. In this module, monitoring progress refers to the IDEA requirement to monitor a student’s progress toward meeting his IEP goals. We use the term progress monitoring to refer to a specific type of measurement (e.g., curriculum-based measurement).

Monitoring a student’s progress is critical to understanding whether the student is responding in a positive way to the services and supports described in the IEP. Data should be collected for every goal listed in the IEP to determine whether a student is making progress toward achieving these goals. The following information brief outlines the process of monitoring a student’s progress toward meeting goals outlined in the IEP.

Monitoring Student Progress Toward Meeting IEP Goals

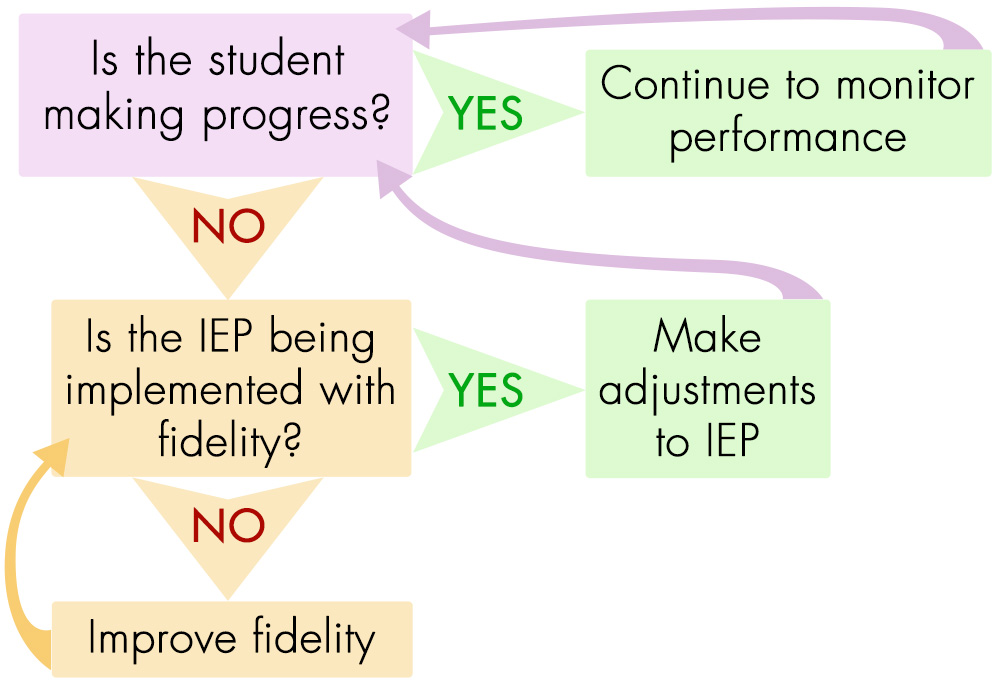

Reviewing a student’s progress at the same time as the initial IEP implementation fidelity check (i.e., after six weeks of implementing the IEP) may also prove valuable. This is an opportunity for the school administrator to informally meet with teachers, individually or as a group, and do the following:

- Check that data on a student’s progress toward meeting her IEP goals are being collected.

- Examine the student’s data to determine whether she is making appropriate progress.

- If yes, continue to implement the IEP and monitor the student’s progress.

- If no, determine:

- Possible reasons for the student’s lack of progress

- Whether adjustments or changes to the student’s instruction or behavior plan can be made by school personnel

- Whether the type or extent of the change(s) that need to be made warrant an IEP meeting

- How these concerns will be communicated to parents so that they remain informed of their child’s progress

By continuing to review a student’s progress throughout the year, school personnel and parents can reasonably predict whether the student will achieve the goals specified in the IEP by the end of the year. Progress reports must be provided to the student’s parents at least as often as those shared with the parents of children without disabilities (e.g., every nine weeks to coincide with report cards).

In the interview below, David Bateman discusses one efficient method to meet with multiple teachers to review progress for multiple students. Next, Breanne Venios shares how her school monitors students’ progress, particularly when there are concerns.

David Bateman, PhD

Professor, Department of Educational Leadership

and Special Education

Shippensburg University

(time: 1:48)

Transcript: David Bateman, PhD

At the end of each marking period, they should sit down with their staff individually and go through each child’s IEP and see if the child is making progress on his or her goals. Now, this may sound like a lot of work, but it really isn’t, and it’s not make-work. Teachers have to report to parents their child’s progress on IEP goals and objectives the same frequency that non-disabled kids get reports, so their teachers are already reporting on whether the child is making progress in his or her goals to the parents. The principal should sit down and meet with the teacher and go through every child on the teacher’s caseload and go through every single IEP. Now, this may seem really time-intensive. It’s not. I sat down with a principal where we did this. We went through 25 kids in 22 minutes, where we ask is the first child meeting his goal in this? Is he making progress on this? Is he making progress on this one? Is he making progress on this one? Talked about anything else we need to know. Nothing we really need to know? Moved on to the next kid. We went through this, and we found a few kids who were not making progress, so we scheduled meetings for them, like, a week or two later, where we could then sit down more with more team members and make some decisions. This is really good for principals to understand what’s going on with the students, because, first, they learn all the responsibilities the special education teacher has, they learn the individual needs of these individual students, and then they also can then make changes based on the data that the teachers have about the child and the child doesn’t go too far without having service changes if they’re not making progress. It’s really easy, simple, and there’s no prep really for the teachers, and the meetings do not have to last long, but you can cover a lot of kids in a short amount of time. And if a kid’s not making progress, make changes. That’s what we need to do for these kids instead of just letting them flounder when progress is not being made.

Transcript: Breanne Venios

I collect data through what we call intervention checklists. If a student is getting a D or below, the teachers have to check what they’ve done and when. And these include following the IEP, calling parents, having meetings, re-teaching. It’s a four-page document of a whole bunch of different interventions. The intervention checklist really helps the teachers question if everything has been done on their end, and if they’ve done everything and they’re still seeing a concern then we move to the child-study team. It moves all the way up to the administration and parents and getting everybody involved, making sure we’re doing everything for this child so they can be successful.

Our school monitors student progress quarterly. So every marking period when our report cards go home, the learning-support teachers put in the progress monitoring sheets for the parents. If there’s a concern, we have the at-risk meeting, and we may have to monitor their progress a little more frequently to make sure that they are meeting their goals. If a student is not making appropriate progress, we have other supports that we could reach out to. We oftentimes bring the team together, and we discuss what all of the people on the student’s team are seeing, so that could include the paraprofessionals, the teachers, the administrators, anybody who is part of the student’s day. We try to collect that data and work together to make sure we have all pieces of the puzzle.

Did You Know?

The IEP team should also reconvene in the event that a student is making more progress than expected. In this case, the IEP team might need to make changes to the IEP, such as creating more challenging goals.

An IEP meeting should be scheduled when a student is not making progress and the type or extent of the required changes warrant a meeting. Additionally, an IEP meeting might be scheduled to discuss revising the IEP for reasons such as:

- The student missed a great deal of school (e.g., because of illness) and has fallen behind in her work.

- Data at the end of the marking period indicate that the student needs more help with assignments or instruction.

- A new evaluation has been completed and there is information that could guide the IEP. The new evaluation could come from either the district or the parent.

- The parent requests additional help for their child because they feel she is not making enough progress.

- The student exhibits behavioral issues that need to be addressed.

Evaluate the Relation Between Student Progress and Fidelity

Both IEP implementation fidelity and student data must be collected if informed decisions are to be made about a student’s program. By examining the relation between the two sets of data, the effectiveness of the program can be determined. When the IEP is implemented with fidelity, clear conclusions can be drawn about the effectiveness of the IEP.

Decision-Making Process for Determining Program Effectiveness

- If the services and supports are being implemented with fidelity and the student’s data show a positive change, it is likely the program being implemented is effective for that student.

- If the services and supports are being implemented with fidelity and there is no change in the student’s performance, it can be inferred that the IEP for that student needs to be adjusted.

On the other hand, if implementation fidelity is low, the relation between the services and supports outlined in the IEP and student outcome data cannot be interpreted with confidence because:

- It is uncertain whether lack of improvement is due to low fidelity or inadequacies in the IEP itself (e.g., unrealistic goals, inappropriate supports and services).

- It is uncertain whether positive outcomes might be improved still further if the IEP was implemented with fidelity.

Keep in Mind

Recall that the IEP process involves a series of seven formal steps, each with clear guidelines on when the IEP should be developed. Although not related to IEP implementation and therefore not covered in this module, keep in mind that there are two more steps in the IEP process:

- Annual Review: An IEP should be reviewed within 12 months after the previous IEP was developed.

- Re-evaluation: The student should be reevaluated at least once every three years.