What should content-area teachers know about vocabulary instruction?

Page 7: Building Vocabulary and Conceptual Knowledge Using the Frayer Model

Within a unit of study are many vocabulary terms that students must learn. Within that list of terms are a few representing key concepts. For example, in a science unit about rocks, the terms in the table below are commonly taught.

| Science, Unit 2 Vocabulary (partial list) | ||

| basalt foliated rocks granite gypsum igneous rocks |

marble metamorphic rocks mineral obsidian pumice |

sandstone sedimentary rocks shale slate unfoliated rocks |

Though students may learn these vocabulary terms independently, they still must understand the relationships between them and thus develop a deeper understanding of the main ideas. Within this vocabulary list, there are three terms that form the foundation for the entire unit: igneous rocks, sedimentary rocks, and metamorphic rocks. Because these terms are central to any substantial understanding of the chapter’s content, teachers might need to spend more time making sure that students really grasp them. In cases like this, using a graphic organizer such as the Frayer Model can be helpful. When used appropriately, the Frayer Model allows teachers to incorporate the elements of vocabulary instruction discussed on previous pages (i.e., selecting words, explicitly defining and contextualizing the term, helping students actively process the word, providing multiple exposures to term).

Introducing and Teaching the Frayer Model

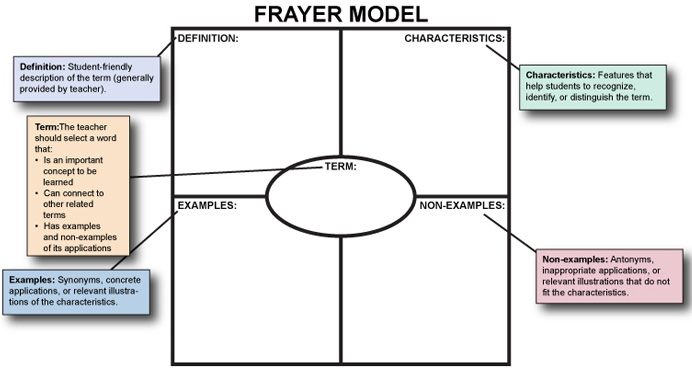

When they introduce this model, it is helpful for teachers to explain why it is useful for building vocabulary and conceptual knowledge. Then they can explicitly teach students what information should go in each section.

Frayer Model

Frayer Model – Completed

- Often have fossils in them

- 75% of Earth’s surface is covered with them

- Coal comes from these

- Layers of sand and mud at bottom of ocean turn into these

- You can usually see them

- Sandstone

- Shale

- Fossils

- Conglomerate rocks

- Gypsum

- Limestone

- Grand Canyon

- Hardened molten

- Lava

- Slate

- Granite

- Pumice

- Obsidian

- Marble

A Frayer model is a square divided into four equal boxes with an oval in the middle. The oval and the four boxes are all labeled with headings. The oval’s heading is “Term.” The upper-left box is labeled “Definition,” the upper-right box is labeled “Characteristics,” the lower-left box is labeled “Examples,” and the lower-right box is labeled “Non-examples.” The term for this Frayer model is “sedimentary rock.” The following text is written under the Definition heading: “Layers of sand of other particles that get pressed together and eventually form a rock; often at the bottom of the sea, rivers, lakes, etc.” Five bullets are listed under the Characteristics heading as follows: “Often have fossils in them; 75% of Earth’s surface is covered with them; Coal comes from these; Layers of sand and mud at bottom of ocean turn into these; You can usually see them.” Seven bullets are given under the Examples heading as follows: “sandstone, shale, fossils, conglomerate rocks, gypsum, limestone, Grand Canyon.” Seven bullets are given under the Non-examples heading as follows: “hardened molten, lava, slate, granite, pumice, obsidian, marble.”

(Close this panel)

Initial instruction about the Frayer Model is heavily teacher-directed and requires teacher modeling. Teachers should demonstrate how to complete the graphic organizer by talking through what they are doing and how they are coming up with the information they enter into the different sections. Teachers should teach students how to use textbooks and other subject-matter materials to generate and discuss the information for each section.

The Frayer Model is not intended to be used as a worksheet for homework, something that would be no more effective than asking students to simply look up the definitions for a list of assigned words. Discussion is an important element of this practice. By filling out the Frayer Model with their classes, teachers help students to apply some of the practices discussed earlier in this module, such as contextualizing terms, actively processing information, and experiencing multiple exposures to terms.

For Your Information

It is not necessary to complete the entire Frayer Model in one lesson. Teachers may use the definition portion to first introduce a term to students. Then they can return to complete other sections of the organizer after students have built some conceptual knowledge by reading the text, seeing demonstrations, or working with associated content.

Click here for a pdf template of the Frayer Model for classroom use.

Examples of Frayer Models from Content Areas

Click on the links below for examples of completed Frayer Models.

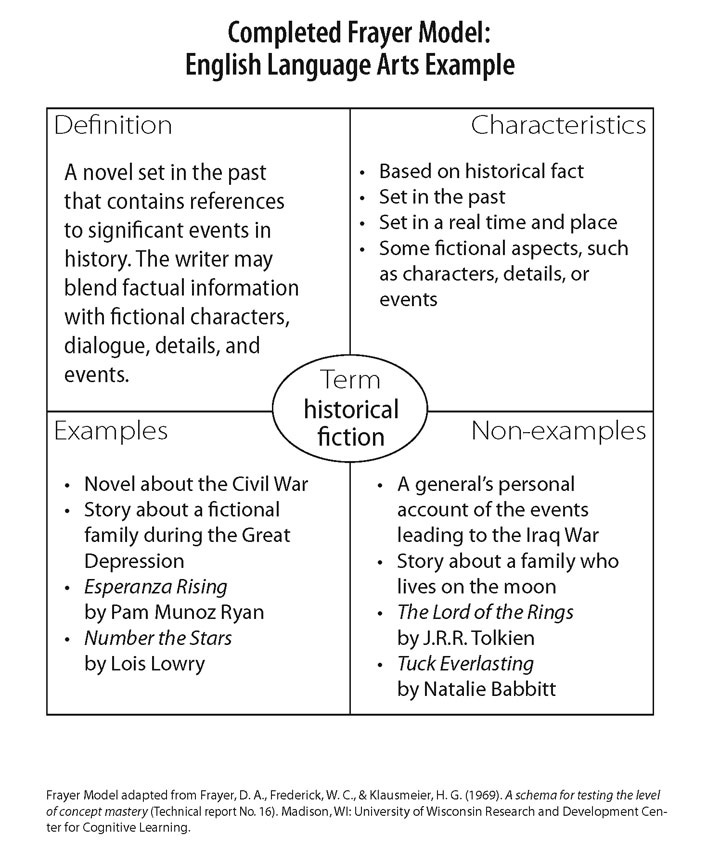

Frayer Model Example: English/Language Arts

English/Language Arts Example: A Frayer model is a square divided into four equal boxes with an oval in the middle. The oval and the four boxes are all labeled with headings. The oval’s heading is “Term.” The upper-left-hand box is labeled “Definition,” the upper right-hand box is labeled “Characteristics,” the lower left-hand box is labeled “Examples,” and the lower right-hand box is labeled “Non-examples.” This is an English Language Arts Example of a Completed Frayer Model, and is titled as such. The Term for this Frayer model, in the oval, is “historical fiction.” The following text is written under the Definition heading: A novel set in the past that contains references to significant events in history. The writer may blend factual information with fictional characters, dialogue, details, and events. Four bullets are listed under the Characteristics heading as follows: based on historical fact; set in the past; set in a real time and place; some fictional aspects, such as characters, details, or events. Four bullets are given under the Examples heading as follows: novel about the Civil War; story about a fictional family during the Great Depression; Esperanza Rising by Pam Munoz Ryan; Number the Stars by Lois Lowry. Four bullets are given under the Non-examples heading as follows: a general’s personal account of the events leading to the Iraq War; story about a family who lives on the moon; The Lord of the Rings by J.R.R. Tolkien; Tuck Everlasting by Natalie Babbitt.

Reprinted with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

(Close this panel)

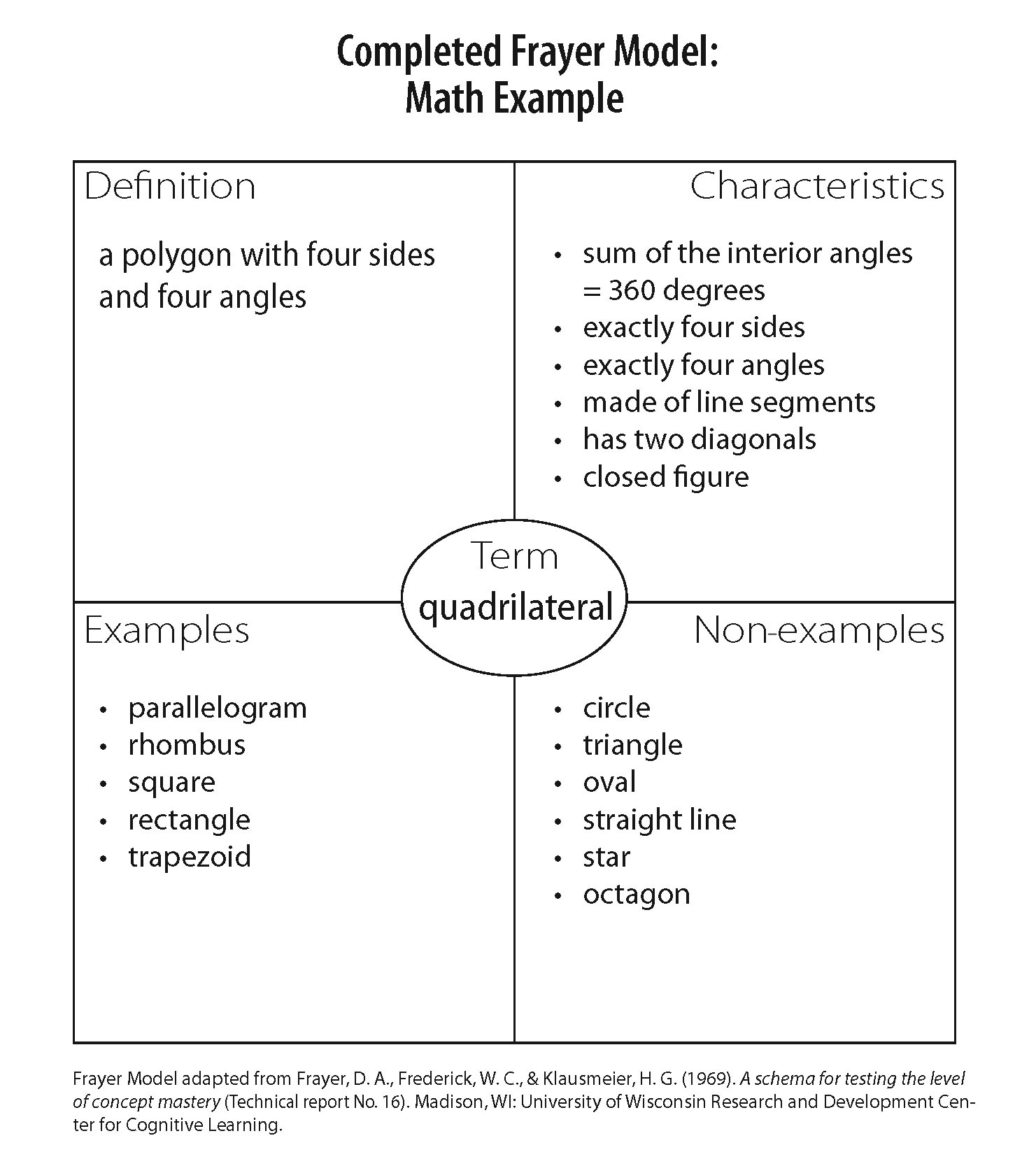

Frayer Model Example: Mathematics

Mathematics Example: A Frayer model is a square divided into four equal boxes with an oval in the middle. The oval and the four boxes are all labeled with headings. The oval’s heading is “Term.” The upper-left-hand box is labeled “Definition,” the upper right-hand box is labeled “Characteristics,” the lower left-hand box is labeled “Examples,” and the lower right-hand box is labeled “Non-examples.” This is a Math Example of a Completed Frayer Model, and is titled as such. The Term for this Frayer model, in the oval, is “quadrilateral.” The following text is written under the Definition heading: a polygon with four sides and four angles. Six bullets are listed under the Characteristics heading as follows: sum of the interior angles = 360 degrees; exactly four sides; exactly four angles; made of line segments; has two diagonals; closed figure. Five bullets are given under the Examples heading as follows: parallelogram; rhombus; square; rectangle; trapezoid. Six bullets are given under the Non-examples heading as follows: circle; triangle; oval; straight line; star; octagon.

Reprinted with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

(Close this panel)

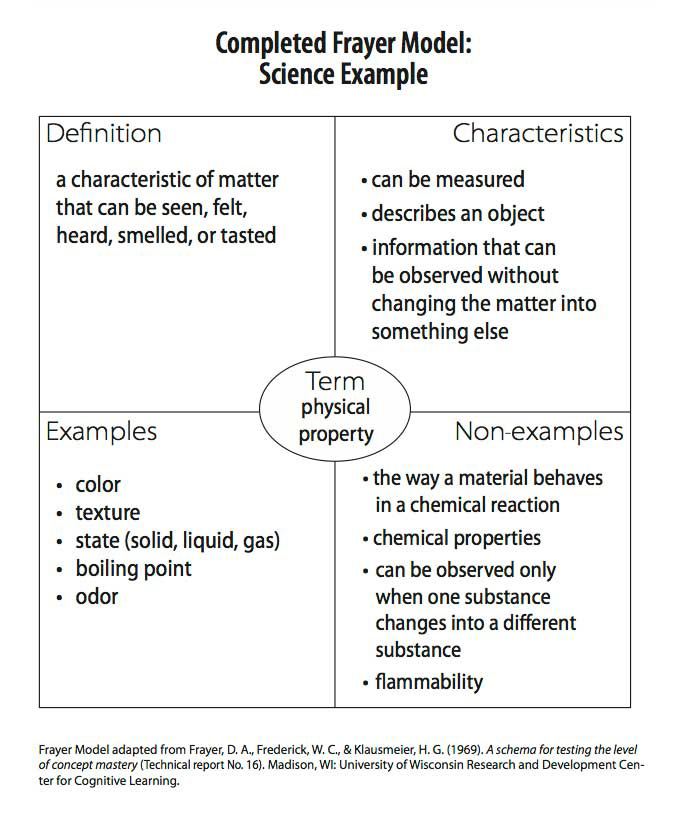

Frayer Model Example: Science

Science Example: A Frayer model is a square divided into four equal boxes with an oval in the middle. The oval and the four boxes are all labeled with headings. The oval’s heading is “Term.” The upper-left-hand box is labeled “Definition,” the upper right-hand box is labeled “Characteristics,” the lower left-hand box is labeled “Examples,” and the lower right-hand box is labeled “Non-examples.” This is a Science Example of a Completed Frayer Model, and is titled as such. The Term for this Frayer model, in the oval, is “physical property.” The following text is written under the Definition heading: a characteristic of matter that can be seen, felt, heard, smelled, or tasted. Three bullets are listed under the Characteristics heading as follows: can be measured; describes an object; information that can be observed without changing the matter into something else. Five bullets are given under the Examples heading as follows: color; texture; state (solid, liquid, gas); boiling point; odor. Four bullets are given under the Non-examples heading as follows: the way a material behaves in a chemical reaction; chemical properties; can be observed only when one substance changes into a different substance; flammability.

Reprinted with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

(Close this panel)

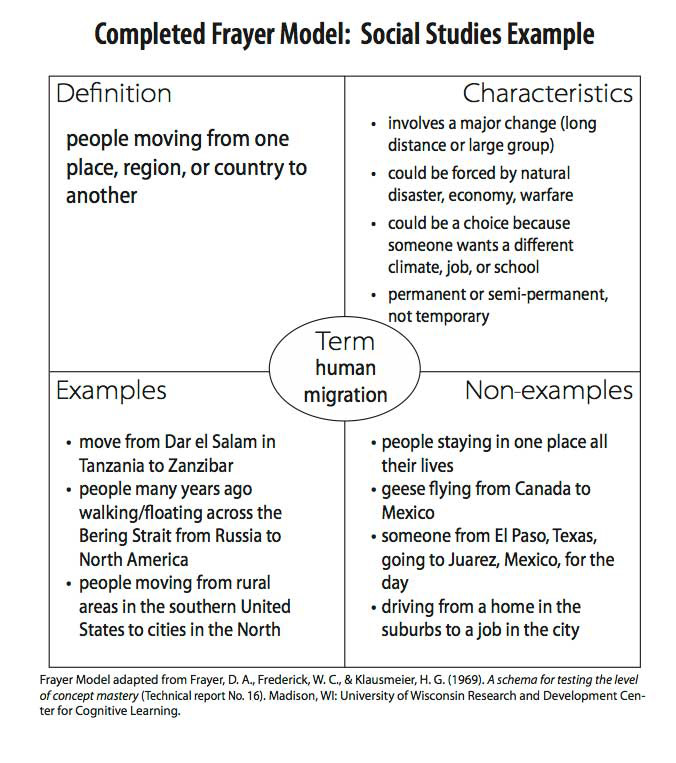

Frayer Model Example: Social Studies

Social Studies Example: A Frayer model is a square divided into four equal boxes with an oval in the middle. The oval and the four boxes are all labeled with headings. The oval’s heading is “Term.” The upper-left-hand box is labeled “Definition,” the upper right-hand box is labeled “Characteristics,” the lower left-hand box is labeled “Examples,” and the lower right-hand box is labeled “Non-examples.” This is a Social Studies Example of a Completed Frayer Model, and is titled as such. The Term for this Frayer model, in the oval, is “human migration.” The following text is written under the Definition heading: people moving from one place, region, or country to another. Four bullets are listed under the Characteristics heading as follows: involves a major change (long distance or large group); could be forced by natural disaster, economy, warfare; could be a choice because someone wants a different climate, job, or school; permanent or semi-permanent, not temporary. Three bullets are given under the Examples heading as follows: move from Dar el Salam in Tanzania to Zanzibar; people many years ago walking/floating across the Bering Strait from Russia to North America; people moving from rural areas in the southern United States to cities in the North. Four bullets are given under the Non-examples heading as follows: people staying in one place all their lives; geese flying from Canada to Mexico; someone from El Paso, Texas, going to Juarez, Mexico, for the day; driving from a home in the suburbs to a job in the city.

Reprinted with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

(Close this panel)

Guided Practice with the Frayer Model

Once students are familiar with using this graphic organizer, they are ready for guided practice. After they’ve discussed the definition as a group, teachers can guide students as they complete the characteristics, examples, and non-examples sections. Watch the video below to see how a math teacher guides her students to generate characteristics of the term dilation and to distinguish examples and non-examples of this word. During this process, students learn to relate dilation to previous lessons and to review their knowledge of other words as they deepen their understanding of the new term (time: 2:05).

Used with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

Transcript: Guided Practice with the Frayer Model

Teacher: I would like for you to use these characteristics to determine if this slide I am going to show you is an example or a non-example of a dilation.

Narrator: The teacher incorporates technology, displaying figures and asks students to use interactive clickers to vote on whether the figures are examples or non-examples of dilations.

Teacher: I just asked you to “Vote A” if it was an example of a dilation or “B” if it was a non-example of a dilation, and here are our results. So most of you voted “B,” which is a non-example. Raise your hand if you can tell me why it’s a non-example. Nicole?

Nicole: Because the shapes are not similar.

Teacher: The shapes are not similar.

Nicole: Because it stretches horizontally but not vertically.

Teacher: Good!

Narrator: The teacher calls on students to explain how they use the characteristics of dilations recorded on their Frayer Model to make their decisions.

Teacher: We just voted that this image is an example of a dilation. Now I want to know who can tell me what type of dilation this is. Raise your hand if you can tell me. Anthony?

Anthony: Enlargement.

Teacher: It’s an enlargement. Very good, yes! And how did you know that?

Anthony: It’s greater than one.

Teacher: Okay, it’s an enlargement because it has a scale factor greater than one. And I see that you’re looking at your Frayer Model and the characteristics. What about the other characteristics? Do they apply?

Anthony: Yes

Teacher: Tell me which ones do.

Anthony: The figures are similar.

Teacher: The figures are similar. Good.

Anthony: The size changed but not the shape.

Teacher: Good! That’s a true statement. The size did change but not the shape. What else, Anthony?

Anthony: The figure doesn’t rotate or flip.

Teacher: Good. You’re right. The orientation stays the same. The figure did not rotate or flip. So those characteristics fit into as to why this is a dilation.

Narrator: As the class discusses, the teacher adds examples and non-examples to the class Frayer Model. Next, the students will work with partners to practice creating examples and non-examples on their Frayer Models.

(Close this panel)

Independent Practice with the Frayer Model

Once students have sufficient experience with the Frayer Model, they should be able to complete sections in class without teacher guidance (i.e., independently, in pairs, or in small groups). When doing so, they should still be required to explain their rationale for the characteristics, examples, and non-examples they chose. It is helpful to ask students to show how they used information from their text or other curricular materials to complete sections. Click on the video to see how small groups of students explain how they came up with examples and non-examples for the vocabulary term dilations (time: 2:07).

Used with permission from the Vaughn Gross Center for Reading and Language Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, copyright © [2010].

Transcript: Independent Practice with the Frayer Model

Narrator: Eighth-grade students in Alma Perales’ class have been using a Frayer Model to increase their understanding of math vocabulary and concepts. In this video, students practice creating examples and non-examples of dilations.

Student 1: So what shapes should we do?

Student 2: Rectangles.

Student 1: Rectangles.

Student 2: Yeah.

Student 1: Okay.

Student 2: We should do a smaller one, 1 x 2.

Student 1: 1 x 2. Make it bigger?

Student 2: Yeah, we should go to an enlargement.

Student 1: Enlargement? Okay.

Student 2: Yes, 2 x 4.

Student 1: Let’s check the characteristics.

Student 2: The size changes but not the shape. A scale factor greater than one is an enlargement. The figure does not rotate or flip. A five…I mean a scale factor between zero and one, creates a reduct.

Student 3: Reduction.

Student 2: My bad. The figures are similar so square, I mean rectangle and rectangle are similar and the size changes but not the shape, so…

Student 1: It’s an enlargement.

Student 2: Yes. And then non-examples.

Student 1: What should we do on non-example? What shape?

Students 2 & 3: Rectangle.

Student 1: We keep that. And let’s check the characteristics. The size changes but not the shape. This is a non-example, because it’s not that. It’s wrong.

Student 2: Yes, this is rectangle, and this is a square.

Student 1: Yes.

Student 2: It went from a rectangle to a square. That’s why it’s a non-example, because the shape changed.

Narrator: The teacher calls the class back together and gives students an opportunity to share their explanations of examples and non-examples. Later, she wraps up the lesson by restating the primary focus.

Teacher: Our main objective today was to generate similar figures using dilations, including enlargements and reductions. And we incorporated the Frayer Model to help build our understanding of the word dilation. And we will continue to use the Frayer Model to increase our understanding of other math concepts in this class.

(Close this panel)

Now listen as Deborah Reed talks about how much of the Frayer Model students can complete on their own (time: 2:50).

Deborah K. Reed, PhD

College of Education, University of Iowa

Director, Iowa Reading Research Center

Transcript: Deborah K. Reed, PhD

In terms of how much of the Frayer Model students should complete or which particular squares they could complete on their own, it depends on a few things. First of all, it depends on their understanding of the format and the function of the Frayer Model. The other thing it depends on is their familiarity with the content of what you’re using the Frayer Model to address. If it’s the first time that students are experiencing that target term that you’re putting in the center of the Frayer Model, and you know that you haven’t taught anything about this concept yet, I’m not sure how students would come up with the information in the squares all on their own. That would be the same thing as assigning the list of words on Monday that the students look up in the glossary or the dictionary and then we take the test on Friday. The purpose of the Frayer Model is to go deeper with the words. If you’re using it to introduce for the first time, it’s incumbent upon the teacher to provide the student-friendly definition. Kids don’t have enough information yet to give you any sort of definition.

Now, you could be going through a text together in which the definition is somewhere embedded in that text, and so it might be a guided instructional activity where we find the definition embedded within this text that we could include on the Frayer Model. And then maybe later on in the reading we’ll find some characteristics. So as we read we’ll pull out these characteristics, and we’ll put them into that square of the Frayer Model and then maybe later on, or while they’re giving us characteristics perhaps, they’ll also show us some examples of the application of it, and so as we read we’ll find those and pull those out and put them onto the Frayer Model. If you’ve covered some instruction in this concept and you’re using the Frayer Model as kind of a cumulative review of what they’ve learned then it’s possible that students could complete more of the Frayer Model on their own, including the definition. By then they’ve built background knowledge, they’ve done some work, they’ve had these multiple exposures and different contexts, they’ve been discussing this in class, and so by then the expectation might be that they should be able to identify, or come up with the definition, be able to list all the important characteristics that will help us recognize this concept, and generate some examples and non-examples. That would be much later in the lesson. Earlier in the lesson, it would be much more teacher-directed.

In the next section of this module, you will learn about reading comprehension, another essential component for developing knowledge in content areas.