What are some ways to involve students in student-centered transition planning?

Page 4: Taking a Leadership Role in IEP Meetings

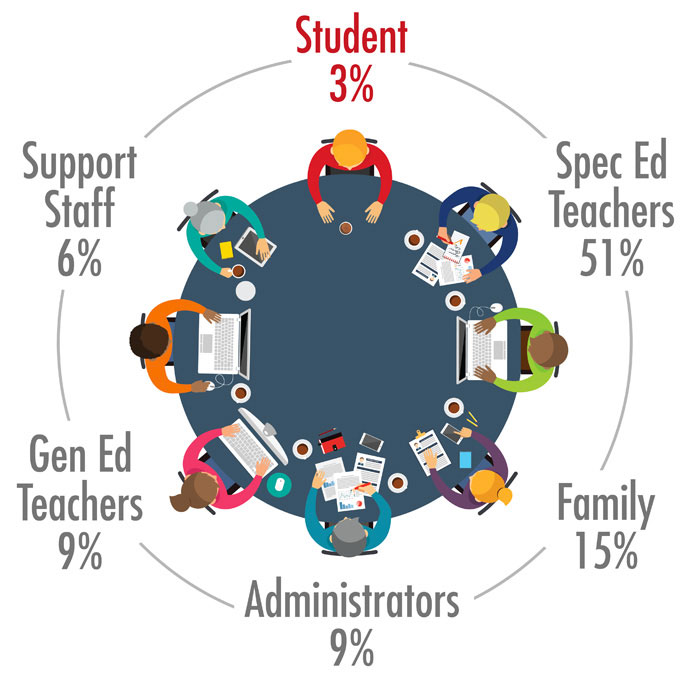

Yet another way educators can involve a student more deeply in the transition planning process is to offer her a leadership role in the IEP meetings. Doing so does not mean that the student will assume full control, nor does it imply that parents and teachers will no longer be able to offer their input. Rather, it means that the student will be allowed to take charge of one or more components of the IEP meeting, for example by introducing the IEP team members or by offering a review of her current performance levels. This type of encouragement takes on additional importance when you recall that students are often not active participants in their IEP meetings or in planning their own futures. In fact, as is illustrated in the graphic below, the average middle or high school student speaks only 3% of the time during an IEP meeting.

Percentage of Speaking Time by Role

This graphic titled the “Percentage of Speaking Time by Role” depicts the percentage of time the various members of the IEP team speak during a typical meeting. The graphic represents a round table with eight people seated with various items in front of them like laptop computers, pens, and coffee cups. Around the outer circle, the role of each of the eight people is indicated, as is the percentage of time each of them spends speaking during the meeting. The roles and percentages are: Students 3%, Special Educators 51%, Family 15%, Administrators 9%, Gen Ed Teachers 9%, and Support Staff 6%.

Note: Although these data were collected over a decade ago, most experts agree that little has changed. Not shown in the graphic: 2% no conversation occurring, 5% multiple conversations occurring at the same time.

When they take on a leadership role in their IEP meetings, students receive real-world opportunities to build self-determination skills that will benefit them far beyond high school into further education or employment. When students develop strong self-determination skills, they are more likely to feel capable of taking control of planning their own lives.

Research Shows

As with their peers, students with significant disabilities who lead their own IEP meetings develop stronger self-determination skills and acquire greater knowledge about post-secondary transition.

To increase students’ level of participation, teachers should familiarize them with the IEP process as well as what they can expect from a typical IEP meeting. Teachers must also make certain that their students are equipped with the tools and supports they will need to take on a leadership role. As always, information should be tailored to meet the needs of the individual students. Click on the headers below to learn more about how teachers can prepare students to lead portions of their IEP meetings.

Before a student can assume any leadership role in the IEP meeting, she first must have a general understanding of both her disability and the IEP process itself. Teachers can help the student to gain this type of understanding by:

- Discussing the student’s disability and how it affects her performance

- Introducing students to applicable laws related to transition (e.g., IDEA, Americans with Disabilities Act)

x

Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA)

glossary

- Providing a basic overview of what is typically discussed during an IEP meeting

- Defining and explaining applicable terms such as IEP, transition, career, and college in language the student can understand

If she is to effectively lead a component of the IEP meeting, a student must first be familiar with the content of the current IEP. To help familiarize the student with the IEP, the teacher and the student together can:

- Review and discuss each section of the IEP

- Discuss which supports and services are beneficial

- Highlight areas of the IEP the student disagrees with or has questions about

To promote student ownership of the IEP meeting, teachers can encourage the student to present assessment data and potential goals. To prepare the student to present this information, the teacher and the student can:

- Review and discuss the assessment data and proposed goals

- Identify how the student can present assessment results using supports that are commensurate with her abilities (e.g., picture cards, a verbal description, a slide presentation)

The level of participation the student will take on should be determined with the student’s strengths, preferences, and experiences in mind. Teachers, in collaboration with the student, should identify the components of the IEP meeting that the student will lead. Some common components that students can take ownership of include:

- Introducing herself or the other team members

- Explaining why the meeting is taking place

- Sharing assessment information

- Talking about strengths, needs, and interests

- Asking questions to clarify information not understood

- Self-advocating for her own interests

- Identifying potential post-secondary goals and supports

- Adjourning the meeting

Once the teacher and student have identified which components the student will direct, the teacher must teach the student the skills necessary to do so successfully. As when teaching any new skill, systematic and consistent approaches tend to work best, although the frequency and intensity of instructional time can vary based on the student’s needs. Skills can be taught in a variety of formats (e.g., in groups, individually) and the frequency of the sessions can vary (e.g., once a week, twice weekly).

Now that the teacher and student have agreed upon which components the student will lead, the teacher should provide opportunities for the student to rehearse what she will say during the meeting. Teachers can make this preparation even more effective by:

- Making the time to practice sections the student will present at the meeting

- Modeling or arranging opportunities for the student to role-play with other students who have previous experience leading their IEP meetings

- Offering corrective feedback and recommendations based on the student’s performance

- Video-taping the student or another student presenting portions of the IEP meeting and allowing the student to watch it while the teacher provides feedback

Teachers should understand that it will take time for students to master the skills they need to lead components of their IEP meetings. They should be persistent and feel confident that their efforts are leading to better outcomes. Teaching the student about the IEP process, selecting which sections she will lead, and providing opportunities for practice are all necessary foundational pieces to helping prepare a student to assume leadership responsibilities. For some students, this might be enough for them to take the lead, whereas for others (e.g., those who are nervous, those with communication challenges) even more supports may be required. As students learn the skills, teachers can offer coaching and support prior to and as needed during the IEP meeting. Forms of support might include:

- Scripts for the student to follow during the meeting

- Picture cards to help the student introduce the sections of the IEP

- Agendas or advance organizers to follow during the meeting

- Technology to support the student’s participation

- Slide presentations to highlight important talking points

- Pre-recorded audio of the student presenting a component of the IEP meeting (e.g., talking about strengths, preferences)

First, Erik Carter discusses some of the ways that teachers can make transition planning more student-centered. Next, he offers greater detail about how to prepare students to take an active role in their transition-planning meetings.

Erik Carter, PhD

Professor, Department of Special Education

Vanderbilt University

Transcript: Erik Carter, PhD (audio #1)

For a teacher who really wants to make their transition planning process much more student-centered, I think the first step is really to make an investment in the preparation of their students and find time within the school day to prepare the students for these kind of meetings. I mean, very few students when even asked about the prospect of coming to a meeting filled with teachers and staff and others are going to probably be excited about that idea. What adolescent would feel really comfortable and confident in that kind of setting? So really preparing students so they understand the purpose of a meeting, the value of their presence and voice in that process, and understanding of the kind of things that would be shared, what their role would be in sharing some of that information and what the roles of others who are going to be invited to that meeting are, it’s really an important part of that preparation.

And I think a second thing for teachers is to think through what kind of process would make sense for students to have that active role in the planning meeting. There are a variety of ways students can be involved in that meeting, everything from having a list of steps that they would work through as part of that process from welcoming everyone to the meeting, making introductions, stating the purpose of that meeting, sharing the progress that they’ve made over the past year, and sharing some of their goals for the upcoming year. That step-by-step process needs to be outlined for students, and deciding what makes the most sense for your students in the context of the meeting is really important.

We encourage teachers to also think about what happens after the meeting. A student-centered planning meeting lasts an hour or two a year, and probably the place where students can have the most benefit and impact is what happens between those meetings. Looking for ways to encourage students’ continued involvement in their own transition plan is a way of making that continue to be student-centered, whether that’s having them self-monitor and self-evaluate their progress and keep track of that over the course of the school year, whether that’s having them share back their progress with team members at various points throughout the school year, or even sharing some of the lessons they’ve learned about having that leadership role with other students who’ve not yet had their transition planning. All those are ways that teachers can prepare and implement and follow-up on this whole idea of student-centered planning meetings.

One of the things that I want to emphasize is that the investment that we’re making of teachers in preparing students for this once-a-year planning meeting really does have a long-term ripple effect on students for the rest of their lives after they’ve exited school. They’re going to be part of these kinds of planning meetings, and the degree to which they’re prepared to contribute to those, to be able to advocate for what they need, communicate the supports and opportunities and linkages that they need to support them is going to be really important for living well long after graduation. So it’s easy for us to think in the very short term, wow, this requires my time and investment that we may struggle to make right now. That investment’s going to have a much longer term impact on students even after the meeting’s done and after they have graduated, so it’s worthwhile.

Transcript: Erik Carter, PhD (audio #2)

It definitely takes time to prepare students for these roles. I would emphasize that it’s not without benefits. It certainly has payoffs. We know that youth who are more actively involved in their own transition planning are ultimately more motivated to work towards those goals and ultimately accomplish those goals. But they have to be equipped with the skills and the knowledge and the attitudes to participate meaningfully and effectively in those kinds of planning meetings.

One approach, I think, is to simply draw upon the growing number of existing programs and curriculum materials that are already out there that have already been designed to equip students in exactly this way, a number of them that offer fairly structured approaches, things like the Self-Directed IEP, the Who’s Future Is It Anyway? curriculum, Take Charge for the Future, Next Steps, and a number of others that have already been evaluated students with disabilities and really lay out a step-by-step what’s involved in leading an IEP meeting. I think incorporating out of those curricula into your class or drawing upon components that you know would be really helpful for a particular student can at least make the planning aspect of that much more efficient for you as a teacher.

There’s also ways that you can involve students in things like role-playing as a group for an upcoming transition planning meeting followed by a time of discussion and reflection on how that went. You might have students who have either graduated or who are a little further along in their transition process share with younger students about their experiences leading their own transition planning meetings, or you could even connect students to any number of community organizations or self-advocacy groups that also gives students opportunities to build those self-advocacy skills and skills they would need to ultimately lead their own planning meetings.

To learn more about involving students in the overall planning for their transitions and preparing them to be active participants in their IEP meetings, we encourage you to listen to Kelly Smoak in the following IRIS Interview:

For Your Information

A variety of resources are available for teachers who wish to prepare their students to assume more leadership responsibilities in their own meetings. Some recommended resources are readily available at the Zarrow Center for Learning Enrichment.

Revisit the Challenge: Donzaleigh

Before the IEP meeting: Mr. Longoria knows that Donzaleigh, a high school junior, needs to practice speaking for herself, a skill she will need when she gets out of school and finds a job. One way he can help her with this is to prepare her to assume more responsibilities in her IEP meetings. With this goal in mind, they meet individually near the end of class once a week for a couple of months to:

- Discuss disability law, the purpose of the IEP, and how leading portions of the IEP meeting provides practice speaking in front of others about her disability and her interests

- Determine what parts of the meeting she is comfortable leading. (Donzaleigh decides to introduce the team members and share her assessment information.)

- Practice conducting introductions and presenting assessment information

During the IEP meeting: Donzaleigh led the parts of the meeting she had practiced, while Mr. Longoria provided needed support (e.g., verbal prompts, an occasional thumbs up). He also encouraged her to speak up about her interest in pursuing a job in fashion design after high school. The team agreed that the goal Donzaleigh proposed would be an important one to include in her IEP.

Revisit the Challenge: Jeremy

Before the IEP meeting: Because several ninth graders, including Jeremy, have never attended an IEP meeting, Mr. Longoria conducts:

- Group meetings for six weeks with these students during the regular school day to provide a basic overview of what an IEP meeting is and what is typically discussed during one

- Individual meetings with each student to talk about his or her current IEP, what supports and services might be needed, and what parts of the meeting he or she is comfortable leading

For his first IEP meeting, Jeremy decides to introduce himself and the other team members, as well as to share his interests. He practices these introductions during the group meetings, and he works individually with Mr. Longoria to create a slide presentation about his interest in working with animals.

During the IEP meeting: Jeremy introduces himself and the other members of the team. He presents his slide show. Mr. Longoria makes certain that the team members are addressing Jeremy and he helps Jeremy respond to their questions. Mr. Longoria also provides whatever support is needed to help Jeremy remain on-task.