What should educators consider when working with students with autism?

Page 6: The Learning Environment

When developing an IFSP or IEP, the multidisciplinary team must consider how to support the learner’s unique needs within an educational context. All educators need to understand how to create a productive learning environment because most autistic learners spend a considerable amount of time in general education classrooms. As illustrated in the graphic to the right, 76% of students spend 40% or more of their day in general education classrooms.

Especially for children and students with autism, educators must create a learning environment that fosters a sense of security and promotes engagement. They can do this by creating structure and predictability, adjusting the sensory environment, and providing visual supports. These proactive environmental considerations are beneficial not only for autistic students but for all learners.

A chart showing the percentages of students with autism served under IDEA who learn in different educational placements: 41% of these students are placed in a general education classroom for 80% or more of the school day, 17% are placed in a general education classroom between 40% and 79% of the school day, 35% are placed in a general education classroom for less than 40% of the school day, and 7% learn in other environments (e.g., separate school, homebound, hospital).

Create Structure and Predictability

Structure is fundamental to helping autistic people thrive. Maintaining a structured classroom environment can help decrease students’ anxiety that, in turn, can make students more receptive to learning and better able to engage in instruction. To increase structure, educators can:

For Your Information

Educators can proactively support a structured learning environment by developing a comprehensive classroom behavior management plan. This plan should outline classroom rules and establish clear procedures for daily routines and activities.

- Establish a predictable schedule: Ensure that the same activities occur at the same time across days or weeks.

- Maintain consistent routines: Make sure that classroom procedures follow a familiar pattern.

- Keep materials organized: Store items in designated, unchanging locations.

- Maintain a consistent physical layout: Minimize changes to the room arrangement.

- Structure time and transitions: Communicate when activities begin and end, the duration of tasks, and how to move between different activities.

comprehensive classroom behavior management

glossary

When changes inevitably occur, educators can support autistic learners by providing advanced notice whenever possible. For example, a teacher might inform students at the start of the day about a scheduled assembly that will alter the usual routine or give them a few days’ notice about an upcoming change in seating arrangements.

Adjust the Sensory Environment

Recall that learners with autism often experience and respond to sensory input differently than their peers. Some might be hypersensitive (i.e., over-responsive) to aspects of the sensory environment; they might become overwhelmed or distracted by bright fluorescent lights, loud noises, crowded spaces, or certain textures. Others might be hyposensitive (i.e., under-responsive), which can cause them to seek additional sensory input through behaviors like fidgeting, rocking, or making noises. To make their classrooms more sensory friendly, educators can:

- Reduce or remove unnecessary decorations and clutter

- Offer ways for students to control their own sensory input (e.g., alternative seating options, noise-reducing headphones)

- Design multisensory learning experiences (e.g., incorporate touch, sound, or movement into lessons)

- Create a designated space where students can engage in sensory activities (e.g., listen to music, use a weighted blanket) or physical exercises (e.g., stretches, wall push-ups)

Research Shows

Noisy, disorganized, and unpredictable school environments can be stressful and overwhelming for autistic students, often causing them to disengage from classroom activities. Conversely, providing calm and structured environments can lower stress and anxiety.

(Esqueda Villegas et al., 2024)

Provide Visual Supports

For Your Information

For visual supports to be effective, educators must explicitly teach students how to use them.

Educators can support autistic learners by using visual supports—any type of visual item (e.g., photos, picture symbols, written words) that helps a student access information, understand routines or expectations, or independently perform a skill or behavior. These supports should be age and developmentally appropriate and should support the student’s independent functioning to the greatest extent possible. Below, explore three categories of visual supports and examples of each.

These types of supports visually designate areas of the classroom where given activities occur (e.g., circle time, independent work). This helps students understand what happens in a certain location, what the expectations are for the area, and where they are expected to remain for the duration of an activity.

Review the slideshow below for examples of how visual boundaries can be created in the classroom.

Boundary areas might be represented by:

- Furniture arrangements

- Rugs

- Taping off an area on the floor

These types of supports serve as non-verbal reminders or prompts. Visual cues can be created using objects, photographs, illustrations, symbols, text, or any combination of media. Autistic learners often process visual input more easily and quickly than spoken language, making visual cues a beneficial way of communicating meaning, expectations, and instructions.

Review the slideshow below for examples of visual cues being used in the classroom.

Visual cues can include:

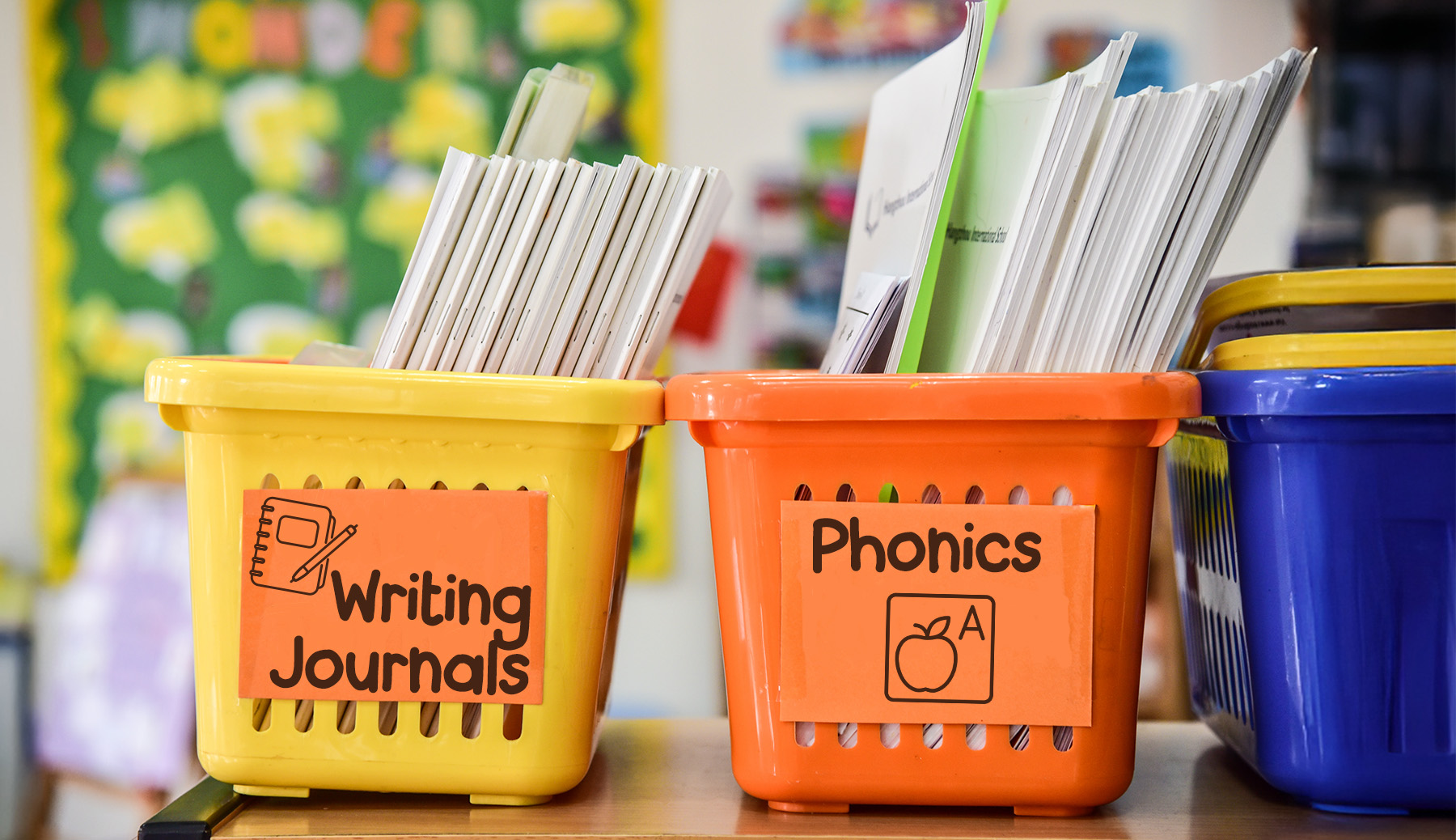

- Labels on items or locations

- Color-coded materials (e.g., by subject area, by individual student)

- Visual depictions of behavioral expectations (e.g., rules posters, volume indicators, sticky note reminders)

- Visual directions for routines or tasks (e.g., steps for washing hands or morning entry routine)

- Visual timers

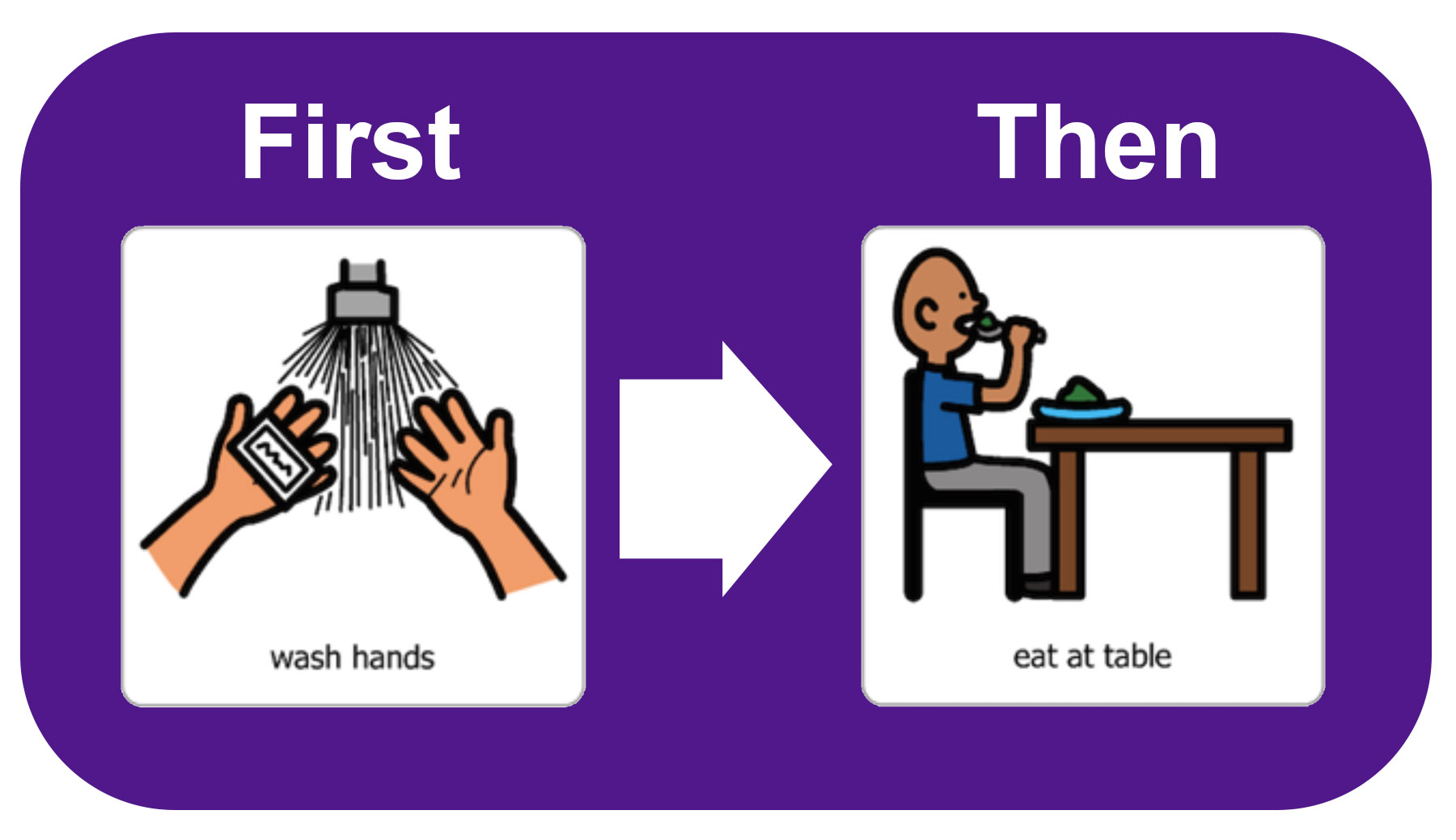

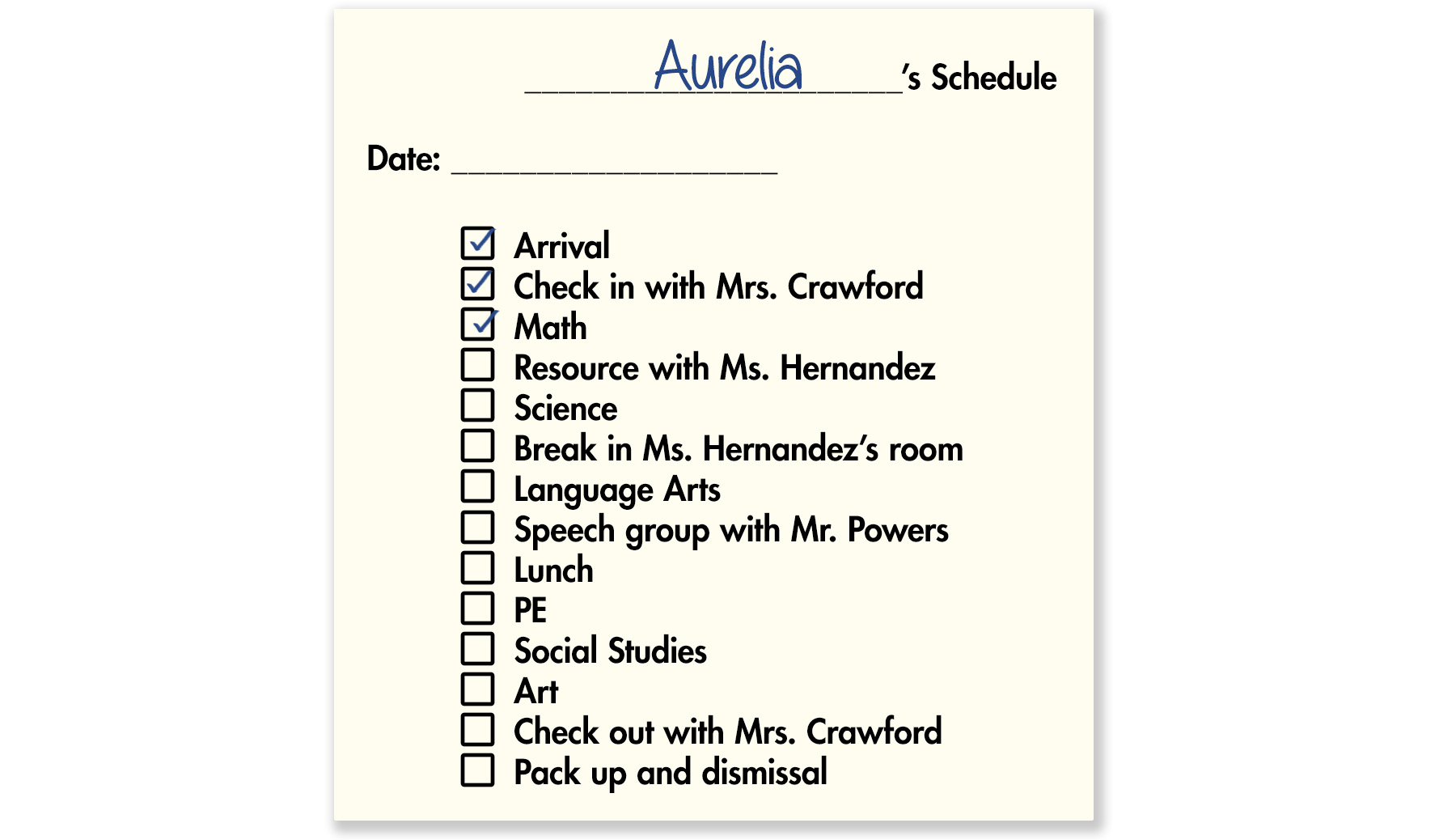

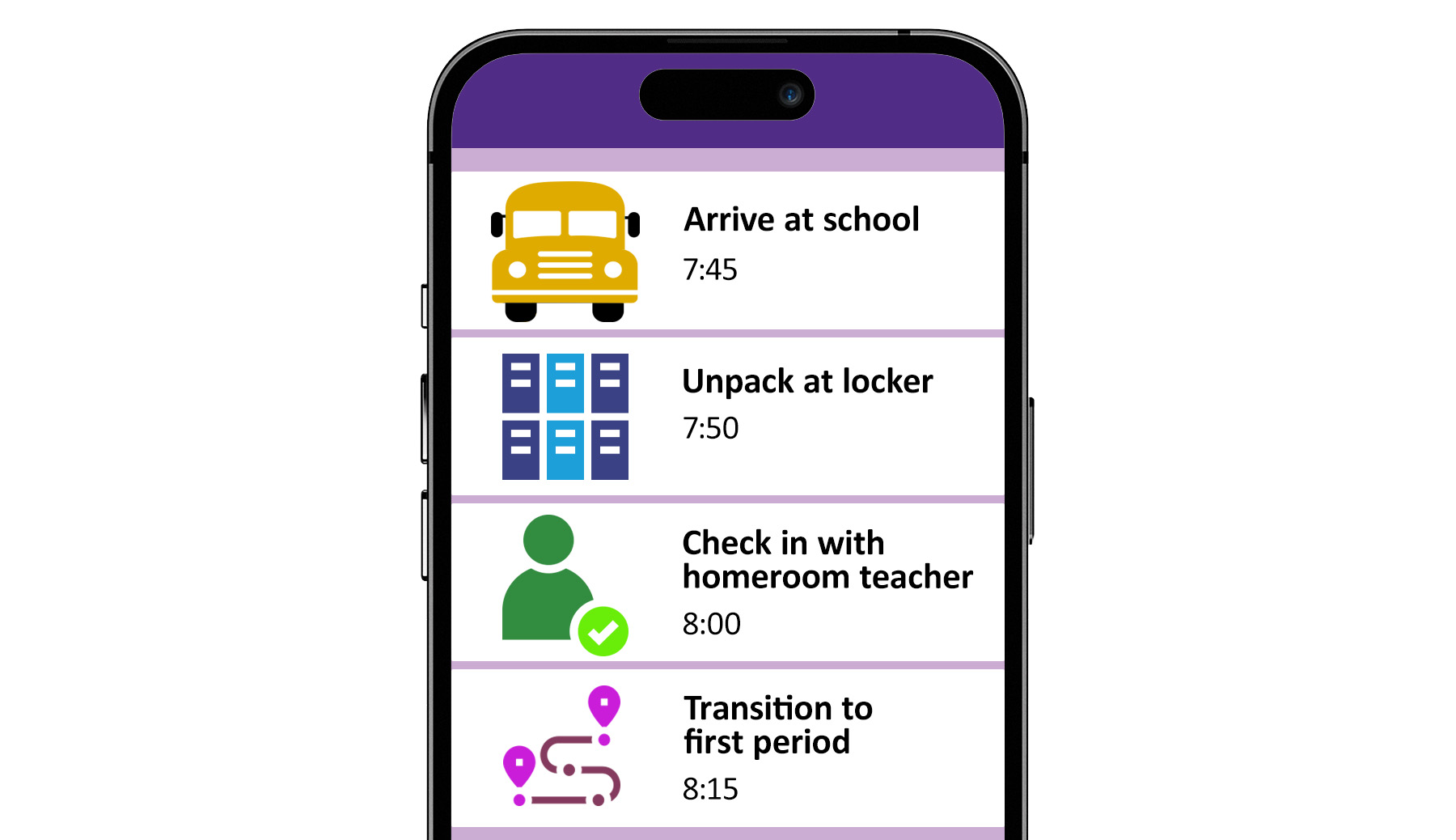

These types of supports communicate a sequence of activities or tasks in a visual format. Visual schedules can use objects, photographs, illustrations, symbols, text, or any combination of media and can span different time frames, from a few activities to an entire day. They help learners with autism understand and anticipate upcoming events, which in turn alleviates anxiety, facilitates smooth transitions, and fosters independence. Visual schedules should be individualized for each learner.

Review the slideshow below for examples of visual schedules for the school and classroom environment.

- First-then boards

- Velcro strips with pictures of activities that can be removed as they are finished

- Written lists of activities with checkboxes to mark off

- Digital schedules on a tablet or other device

first-then board

glossary

Research Shows

The evidence base for visual supports is robust, with studies demonstrating positive impacts on:

- Social, academic or pre-academic, and adaptive or self-help outcomes for autistic students ages 3 to 22

- Communication, play, school readiness, and behavioral outcomes for autistic students ages 3 to 14

- Vocational skill outcomes for autistic students ages 6 to 22

- Motor skill outcomes for autistic children birth to age 2

(Esqueda Villegas et al., 2024)

For additional information about content discussed on this page, review the following IRIS resources. Please note that these resources are not required readings to complete this module. Links to these resources can be found in the Additional Resources tab on the References, Additional Resources, and Credits page.

Classroom Behavior Management (Part 1): Key Concepts and Foundational Practices This module overviews the effects of disruptive behaviors as well as important key concepts and foundational practices related to effective classroom behavior management, including cultural influences on behavior, the creation of positive climates and structured classrooms, and much more (est. completion time: 2 hours).

Classroom Behavior Management (Part 2, Elementary): Developing a Behavior Management Plan Developed specifically with primary and intermediate elementary teachers in mind (e.g., K-5th grade), this module reviews the major components of a classroom behavior management plan (including rules, procedures, and consequences) and guides users through the steps of creating their own classroom behavior management plan (est. completion time: 2 hours).

Classroom Behavior Management (Part 2, Secondary): Developing a Behavior Management Plan Developed specifically with middle and high school teachers in mind (e.g., 6th-12th grade), this module reviews the major components of a classroom behavior management plan (including rules, procedures, and consequences) and guides users through the steps of creating their own classroom behavior management plan (est. completion time: 2 hours). |