How can faculty present important content to be learned in ways that improve student learning?

Page 2: Learner-Centered Learning Environments

Learner-Centered Learning Environment

In a learner-centered learning environment, the instructor should design ways to uncover the knowledge, skills, interests, attitudes, and beliefs of every learner. Learner-centered instructors know that students are not blank slates—that a conceptual understanding, or misunderstanding, of a subject is based on what they bring with them, including the students’ social and cultural traditions and experiences. Moreover, because people’s thoughts and beliefs are often tacitly held, it is important to create many opportunities to draw those beliefs to the surface and make them visible to the learner, the instructor, and the classroom community, as appropriate. The more visible a student’s thinking becomes, the more opportunity an instructor has to understand the student’s misconceptions and correct them. In this way, the instructor can build upon what the student already knows and is able to do.

In a learner-centered learning environment, the instructor should design ways to uncover the knowledge, skills, interests, attitudes, and beliefs of every learner. Learner-centered instructors know that students are not blank slates—that a conceptual understanding, or misunderstanding, of a subject is based on what they bring with them, including the students’ social and cultural traditions and experiences. Moreover, because people’s thoughts and beliefs are often tacitly held, it is important to create many opportunities to draw those beliefs to the surface and make them visible to the learner, the instructor, and the classroom community, as appropriate. The more visible a student’s thinking becomes, the more opportunity an instructor has to understand the student’s misconceptions and correct them. In this way, the instructor can build upon what the student already knows and is able to do.

Failing to make a student’s thinking visible can be problematic. For example, some students may do well at memorizing content and will score well on a test, but during the next assignment or discussion they might revert to ideas and beliefs that are based on their undiscovered misconceptions. Listen to the audio clip below to further your understanding of learner-centered learning environments (time: 0:48).

Transcript: Amani Reflects on Her Student’s Experience

When Kellie and Amani met to discuss the learner-centered section of the module, Amani shared an incident involving Mark, one of her students who was currently doing student teaching. Mark had previously scored very well on his tests and assignments. However, when he taught his first lesson, it didn’t go well. One of his students had hearing problems, so Mark spoke very loudly and slowly, and he used many hand gestures. The rest of the class laughed and was inattentive. Finally, Mark lost his concentration and then his composure. Later, when he and Amani discussed the incident, she found out that Mark’s only experience with deaf or hard-of-hearing individuals was with an elderly, irascible grandparent who always insisted that he speak up.

Obviously, this type of tacit misconception, whether addressed or not, is likely to have an effect on more than one exceptional student in this future teacher’s career.

A learner-centered classroom seeks to avoid the dilemma of undiscovered thinking by:

- Presenting students with subject-related problems or challenges

- Soliciting their thoughts and ideas about how to solve the problem

- Asking them to explain the reasons behind their thinking

Finally, a passage from the text How People Learn does a succinct job of summarizing an instructor’s role in being learner centered:

“If teaching is conceived as constructing a bridge between the subject matter and the student, learner-centered teachers keep a constant eye on both ends of the bridge. The teachers’ attempt to get a sense of what each student knows, cares about, is able to do, and wants to do can serve as a foundation on which to build bridges to new understandings.” (National Research Council, 2000, p. 136)

Now that you’ve had a brief summary of a learner-centered learning environment, you might like to take a few minutes to interact with the Challenge scenarios below.

Fish is Fish

The Fish is Fish movie (time: 1:34) and audio explanation by John Bransford (time: 2:39) illustrate how we construct new knowledge based on existing knowledge and conceptions.

Transcript: Fish Is Fish

In a moment, I’m going to summarize for you a children’s story written by Leo Leonni. The story is called Fish Is Fish. After listening, I’ll ask you to give reasons why you think it is or is not relevant to learning and, if it is, to give some samples of your own that will illustrate this. A tadpole and a fish live together in a pond. They are intensely curious about the world outside. Eventually, the tadpole grows into a frog and is able to leave the pond and travel onto the land. A short time later, he returns to the pond and tells the fish what he saw. “There are marvelous creatures called birds,” said the frog. “They have beaks and two feet, but most amazingly, they have wings and can fly.” “I’ve got it,” said the fish. “What wonderful information; I know exactly what you mean.” “There are also things called cows,” said the frog. “They have four legs, and some of them have horns, and some have utters, and they chew grass.” “Say no more,” said the fish. “I can see a cow as clearly as if it were right in front of me.” “Well, that’s not all,” said the frog. “Let me tell you about these creatures called people. They walk on two legs, but they also have two arms and come in all kinds of sizes.” “Perfect,” said the fish. “I can picture them now.” There’s more to Leonni’s story, but this is the part that’s important to this Challenge. Do you think it’s relevant to human learning, and, if so, can you give some Fish Is Fish examples of your own that will illustrate this?

Transcript: John Bransford, PhD

Well this story about Fish Is Fish, I think, is really powerful because it illustrates the constructive nature of knowing the fact that the only way we can know something new is to construct an interpretation based on what we already know. And so you can see in the story how the fish did that based on the frog. But there’s many, many real-life analogs to this. So in the book How People Learn, for example, we talk about some young children who initially believe that the earth is flat. And of course that fits all their experiences, and then people say, “No, no, it’s round like a ball.” You can even show them a picture of the earth and space, and so kids go, “Oh, oh yeah, I got it,” much like the fish says. And then if you really probe and get them to draw, what they do is they have this round ball with the flat part on top and we live on the flat part. So they’re preserving their kind of Fish Is Fish construction. You see this in all kinds of areas of science and so forth where people come in with preconceptions like, “Oh, pollution is something that chokes animals or poisons animals, and that’s all it is,” or that “Electricity is like water flow.” And it turns out that unless you directly address these preconceptions that students bring in, you will not stop their Fish Is Fish activities once they leave the course. The other interesting thing is almost any faculty meeting illustrates Fish Is Fish. So you say, “OK, we agreed on something.” And then you say, “All right, what do you think we agreed on?” And someone says, “Point A,” and someone else says, “No, no we agreed on B,” “No, we agreed on C.” And so often this Fish Is Fish can be used to dispel the kind of angst and sometimes even anger that comes up when people: “Oh wait, we’re not understanding,” and you: “Of course we’re not.” It’s hard to do that; this is the constructive nature of knowing. And it also illustrates, then, the importance of working to make everybody’s thinking as visible as possible, because if we don’t do that, then we all end up with different constructions of reality that don’t fit what others intend. And the one other part of this is hugely important is our interpretations of other people, especially people who may be different from us for a number of different reasons, whether they’re from a different culture or whether they have certain disabilities. And it’s amazing the kind of constructions we can make based on stereotypes and assumptions. And one of the things that we need to do, that Fish Is Fish can remind us of, is always actively look for the story behind the story. Question the initial assumptions you have about someone, especially if they tend to be negative, ’cause almost undoubtedly you’ll find that there’s a positive streak there, if you take the time to look for it.

Memory

The following movie (time: 1:03) and audio explanation by John Bransford (time: 1:34) illustrate that making the right instructional decisions will help meet a student’s needs.

Transcript: Identify learning strengths

A seventh-grade girl, Jennifer, is having difficulty in school. Her parents noticed that she has an excellent visual memory. She can watch complicated dance steps and easily repeat them. But her verbal memory seems to be below average. If she hears a typical ten-word sentence, she will not get all of the words. Similarly, she frequently leaves out things when she talks. She might say something like, “Isabelle is different,” but leave out that she’s talking about someone on a TV show. People in the school are concerned with Jennifer’s poor memory and decide to place her in a special class where the curriculum is simplified. The regular science class is rigorous and includes not only lots of reading but time-consuming laboratory experiments. But the simplified science class drops the laboratory so students can concentrate on the facts they need to learn.

What are your thoughts about the school’s reactions to Jennifer’s difficulty?

and

What kinds of theory and research might help us better understand people like Jennifer and the kinds of learning activities they need?

Transcript: John Bransford, PhD

Well, this is a case that a friend of mine, John Black, recently told me about, that he knew about personally. And it really affected the life of this young girl. And she was, he knew he’s actually a learning scientist and he knew that she was very good with visual memory, not that good with language memory. The people in the school said, “Yes, we know that there’s a learning disability here of some kind, and we’re going to fix it by simplifying the science class.” And this is typically the approach that people take for special-needs kids. Let’s “simplify it” without really knowing what does “simplify” mean. And in this case, what they did is put the girl, as I said at the Challenge, into the text-only condition absolutely the worst condition she could ever be in, ’cause that was where her problems were and they took out the lab. He actually was asked to consult on this case, and he eventually talked the school system into taking her out of the quote “simplified course” and putting her in the one that had the laboratory, and in fact she flourished in that. Doesn’t mean she got an A: She got a C, but, boy, that was quite a victory for her. And it was in large part because that lab with the visual aspects and her ability to see things played right to her strength. So, again, this whole idea of what does it means to “simplify” really needs to be looked at very carefully in terms of the special needs of the kids who are really what we care about.

Learner-Centered Example

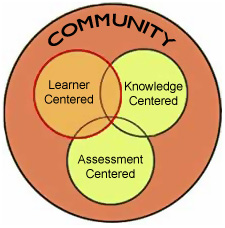

Take a look at the Initial Thoughts questions below from the What Do You See? Perceptions of Disability module on disability awareness. These questions offer one way to get information about a student’s background knowledge, values, and beliefs by asking about her or his personal thoughts, feelings, and perceptions. Incorporating learner-centeredness is foundational to the How People Learn theory and one necessary element to enhancing lifelong learning.

Module: What Do You See? Perceptions of Disability

Initial Thoughts

Write down your initial reactions to the pictures you have just seen by answering these questions:

- What did you see?

- What feelings did you have about the photos?

- What did you think about the individuals in this Challenge?

- Do perceptions matter?