How can faculty present important content to be learned in ways that improve student learning?

Page 4: Assessment-Centered Learning Environments

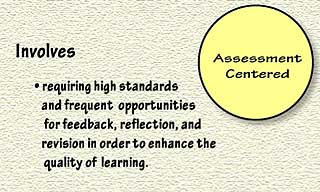

Valuable information for faculty and students may be obtained from assessment measures. Obviously, these can be created in various formats and collected in a number of ways. Important features of an assessment-centered learning environment include:

Valuable information for faculty and students may be obtained from assessment measures. Obviously, these can be created in various formats and collected in a number of ways. Important features of an assessment-centered learning environment include:

- High standards

- Frequent opportunities for feedback, reflection, and revision, in order to enhance the quality of learning

Having high standards means that the instructor expects everyone in the class to succeed, not because expectations are lowered for some but rather because the instructor creates opportunities for each student to meet these standards.

Formative Assessment

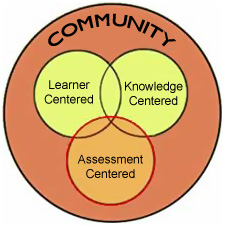

One important way an instructor might create these opportunities is through formative assessment. An environment of formative assessment overlaps a learner-centered environment on the issue of making students’ thinking visible, a prerequisite to helping them meet high standards.

An environment of formative assessment is one designed to provide continual feedback about preconceptions and performances to both learners and instructors. This feedback, which may be from any number of sources including texts, media, instructor comments, and class discussions, allows learners to reflect on and revise not only their proposed solutions to a problem but also the way they approached the problem. The feedback from formative assessments can also help instructors by suggesting ways they might improve their instruction and by identifying where and how specific learners need further help.

A critical function of formative assessment is to help learners develop metacognitive skills. This includes developing students’ abilities to take some measure, over time, of what they have learned and what they are struggling with. It also involves learning to recognize and differentiate between the strategies that are working well for their own problem-solving and those that are not as effective. In other words, helping learners to develop their metacognitive abilities means helping them to develop the “habits of mind” that will allow them to consistently assess and improve their own learning processes and progress, as opposed to always relying on others to assess them (Bransford, J. D., Vye, N. J., & Bateman, H., 2002).

Listen to the audio clip below to further your understanding of assessment-centered learning environment (time: 1:26).

Transcript: Kellie Reflects on Assessments

When Kellie and Amani met to discuss assessment-centered learning environments, they both agreed that grading checkpoints like quizzes, tests, and papers were common practice. They also felt that assessments were needed but that these methods did not allow some students to show what they had actually learned.

Then Amani shared a story about a former student who was an English language learner. It took a few weeks of class for Amani to realize that this student was having some disconnects. So she invited him to meet with her on a weekly basis to review topics he didn’t understand. When other students heard about these weekly gatherings, they asked if they could join in. As the weeks passed, Amani came to realize that many of her students were having trouble grasping all of the important content. She also came to realize that the individual misunderstandings of each student often varied as much as their individual cultures and backgrounds. By the end of the academic term, several things were obvious. First, regulars at the review sessions were scoring well on tests and assignments. Second, those students were now recognizing the misconceptions of their classmates. And, third, the discussion group members were making solid contributions that furthered everyone’s learning and understanding. Amani said it was now clear to her that intentional, individual, and well-designed formative assessment significantly improved her students’ learning.

Summative Assessment

Whereas formative assessment measures learning progress in order to encourage reflection and revision, summative assessment should be designed to measure the results of learning. Thus, formative assessment might be viewed as part of the journey of learning, whereas summative assessment might be viewed as a periodic gathering of data points that provides quality control and serves the important function of legitimizing credentials. For more information about summative assessment see Knowing What Students Know (National Resource Council, 2001).

Now that you’ve had a brief summary of an assessment-centered learning environment, you might like to take a few minutes to interact with the Challenge scenarios below.

Test as a Gift

John Bransford contrasts the difference between formative and summative assessment in the movie “Test as a Gift” (time: 0:35) and in the subsequent audio (time: 1:31).

Transcript: Test as a Gift

During the December holiday season, a local newspaper ran a cartoon showing students in a classroom who had each received a wrapped present from their teacher. Upon opening the present, each student discovered the contents: a geometry test. Needless to say, the students were not pleased with their gift. And people who viewed the cartoon could easily understand the students’ anguish. Tests are more like punishments than gifts. Here’s the question I want you to consider. Is there any way that a test could be perceived as something positive?

Transcript: John Bransford, PhD

Well, this was a very interesting challenge to see people’s answers to, especially, say, students in college because most of them say, “What?! There’s no way a test could be a gift. It’s a test, and we hate them.” And in a sense, they’re right; I mean, they’re thinking of tests like we often give them in classes, as you turn in a paper and get a grade. You take your test, and you get a grade, and then you move on to something else. Well, that’s called summative assessment. And that’s assessment after a unit or a course or maybe the standardized test at the end of the year. A much more interesting one from a cognitive perspective is what’s called formative assessment. This is assessment where what you do is give people feedback about what they’re learning and give them a chance to revise so that they can improve. And that chance to revise and improve is hugely important. But all of us need that all the time, and if you think back to the Fish Is Fish story, it’s one of the best illustrations of why you need to give people a chance to make their thinking visible. For example, see what kind of fish they construct, then give them feedback and help them revise. And it’s useful not only for the student but for the professor, as well. So if you set up those kind of conditions, then I find boy students do treat “tests or formative assessments” as a gift. It’s one of the best ways to help them be sure of what they’re learning and to help you as a teacher understand what they understand, as well.

In the following audio clip, James Pellegrino describes the importance of assessment practices (time: 2:47).

James Pellegrino, PhD

University of Illinois, Chicago

Distinguished Professor in Psychology and Education

and Co-Director of the Center for the Study of Learning,

Instruction, and Teacher Development

Transcript: James Pellegrino, PhD

The point of controversy and I think the point which is of greatest concern to many in the educational community and among many psychologists and educators is the fact that most current assessment practices, including standardized tests, as well as many of the practices of teachers in classrooms, are grounded in outmoded theories of learning and knowing. One way of saying this is that we have developed a technology of testing which is rooted in a simple conceptualization about the nature of knowledge. We sometimes refer to it as the associative theory of knowing, where knowledge is essentially the accumulation of facts and procedures, discrete bits of information that collectively define what it means to know something in a given subject-matter area. The result of that is we create tests that have lots of specific items on them which get at those bits and pieces of knowledge. We sample from the whole universe of what it is that a kid might know, and then we figure that that’s a pretty good estimate of the totality of their knowing. But what’s wrong with that? What’s really wrong with it is that it doesn’t do justice to all the research that we now have about what it means to really know and how people learn. In reality, the nature of knowing and understanding is really rooted in not just having discrete bits of information but how that knowledge is organized, how it’s connected together, how people are able to use that information fluently to solve problems, answer questions, recognize patterns. And it is that aspect of knowing that most current assessments fail to get at. And the primary reason is they weren’t designed using that theory of knowing and the empirical knowledge that we have about how kids understand particular concepts and how that understanding develops to actually develop more refined and more sensitive kinds of assessment instruments. What we’re saying is we have a much more detailed and rich and powerful theory of knowing, which gives rise to ideas for different kinds of observations that we would make if we wanted to get at what students really know. And it supports much more complex and much more interesting and diagnostically useful ways of interpreting that data.

Assessment-Centered Example

Formative Assessment

For an example of formative assessment, view the IRIS Module activity in What Do You See?: Perceptions of Disability. This is an example of formative assessment because the questions posed to students allow them to:

For an example of formative assessment, view the IRIS Module activity in What Do You See?: Perceptions of Disability. This is an example of formative assessment because the questions posed to students allow them to:

- Provide continual feedback about preconceptions and new content learned

- Reflect on their approaches and responses to the activity

- Determine the effectiveness of their learning methods

- Use this information to self-assess their learning

Summative Assessment

View a few of the Assessment questions from the IRIS Module Addressing Disruptive and Noncompliant Behaviors (Part 1): Understanding the Acting-Out Cycle. These Assessment questions allow students to demonstrate subject mastery in both factual knowledge and content application. The instructor and the students can use these results as a measure of student learning.