How can faculty present important content to be learned in ways that improve student learning?

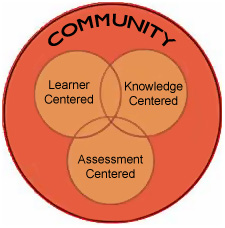

Page 5: Community-Centered Learning Environments

The foundation of a community-centered learning environment is the fostering of explicit values or norms that promote lifelong learning. An example would be students feeling confident to ask questions and not being afraid to say, “I don’t know.” This is in contrast to a course in which the norm is “Don’t get caught not knowing something” (National Research Council, 2000, p. 25).

The foundation of a community-centered learning environment is the fostering of explicit values or norms that promote lifelong learning. An example would be students feeling confident to ask questions and not being afraid to say, “I don’t know.” This is in contrast to a course in which the norm is “Don’t get caught not knowing something” (National Research Council, 2000, p. 25).

Community-centered learning environments also contribute to the aligning of students’ and instructors’ course expectations. On the first day of a course, it is likely that there are as many sets of expectations and assumptions about the course as there are people in the classroom. When instructors take the time to make course goals and expectations explicit, they are taking the first step in gaining their students’ cooperation. When instructors also take the time to elicit their students’ expectations and assumptions, they are starting down the road to a truly collaborative learning environment.

When students understand that their instructor is paying attention to their needs, both individual and collective, they are much more likely to become active participants in the construction of a classroom community that helps all of its members to achieve their learning goals.

Listen to the audio clip below to further your understanding of community-centered learning environments (time: 1:14).

Transcript: Expectations

As Kellie considered what was involved in creating a community-centered learning environment for her courses, she once again remembered “Professor Lecture.” That’s how she’d come to think of him. He had tremendous expertise and gave excellent presentations. But now she realized that he had two well-defined but unspoken expectations. Of himself, he expected to deliver well-prepared monologues, and of his students, he expected attentive note-taking. Excessive questions or discussion were a distraction from what he considered to be learning. These expectations, though unspoken, were nevertheless very real classroom norms. Kellie also began to understand that only those students who excelled under this norm were appreciated and considered serious and capable.

This approach to college instruction left many students behind. Furthermore, the lack of shared expectations and collaborative opportunities created an atmosphere of “everyone for themselves.” The result was a sense that this course was about selecting talent rather than developing talent. And suddenly she wondered how many of her former classmates had left that course feeling discouraged.

It is important to understand that this audio clip does not argue against high standards as defined in the assessment-centered section. On the contrary, a classroom community in which students and their instructor support all class members’ learning highlights a major goal of community-centered learning environments: to help every student to “develop competence and confidence” (Bransford, Bropy, & Williams, 2000).

Bransford, Vye, and Bateman (2002) note several likely positive outcomes for students in classrooms with strong communities. These students:

- Are willing to allow theirs peers to see that they do not know everything

- Improve their abilities to solve complex problems

- Focus their learning goals on mastering the content rather than on learning the material for the sake of a good grade

The authors summarize by stating that, “Classroom communities that provide stimulating, supportive, and safe environments in which students are not dissuaded from challenging themselves due to fear of failure and ridicule are the classrooms in which students become lifelong learners” (Bransford, Vye, & Bateman, 2002).

One way the IRIS Center has attempted to embrace the idea of community-centered learning environments is by creating a community of practice. We have provided our research and implementation sites with conceptual tools, in the form of online modules and materials, and ongoing support in the hope of facilitating a community of practice among faculty and students. It is our hope that the sharing of experiences about their applications will nurture an ever-expanding community of practice and that it will have a positive effect on student learning outcomes.

Now that you’ve viewed a brief summary of a community-centered learning environment, you might like to take a few minutes to interact with the Challenge scenarios below.

What an Answer

The following movie(time: 0:53) and audio (time: 1:12) by John Bransford illustrate how using classroom norms can help to develop problem-solving skills and adaptive expertise.

Transcript: What an Answer

Imagine this classroom scenario. An instructor frequently presents her students with difficult problems and asks them to try their best to generate solutions, even if they fail. After a designated period of time, there’s a class discussion where each student talks about their own answers and strategies. The instructor leads these discussions and does a good job giving feedback to the many ideas and clarifying how the problems she has presented can be solved. However, this problem-solving approach is hard work for everyone and they’re getting impatient. Halfway through the course, they respectfully ask the instructor to tell them how to solve the problems rather than to make them waste so much time trying on their own. After all, they rarely get the answers right anyway. What might the instructor do to convince the class that her problem-solving approach is good for them? Or is the approach not as beneficial as she thinks?

Transcript: John Bransford, PhD

Well, this challenge gets at an issue that so frequently comes up from students, and that is after a while they go, “Come on let’s be efficient, just tell me the answer. You’re supposed to be the teacher, and I’m here to learn.” And in many ways, this absolutely makes sense. I mean, for many things, you know, if you want me to learn how to put together a bicycle, I just want to know how to do it. I don’t need a theory, a lecture on the theory of physics at the same time. But one of the important things in helping people see how they need to be prepared for life goes back to “look at the world outside of school.” And especially what Peter Vail called the “white water world,” and the fact that, if you’re going to be prepared for a white water environment, you gotta be prepared to learn to solve problems on your own. There’s no mentor at whose feet you can sit. There’s no textbook that you can read. You can’t be spoon fed in those situations. So, sometimes, sure it’s fine to sit at the foot of the mentor, just get the information, be efficient. At other times, though, as part of your career you really need to learn how to learn on your own, struggle on your own, and learn as much as possible to solve problems on your own.

Listen to an audio perspective from Peter Vaill about new paradigms for teaching and learning at the college level (time: 0:39).

Peter Vaill, PhD

Professor of Management

Antioch University

Transcript: Peter Vaill, PhD

I think one of the keys to improving teaching is for the professor to become more of a learner. The present culture says the professor is the expert and the student is the learner. And not very many faculty members go into a class expecting to have a powerful learning experience. But the professors who do go into a class as learners and come across to the student as learners come across with this kind of almost childlike openness and wonder and excitement and willingness to explore and willingness to ask questions. Those are the professors that the students really love and relate to.

Community-Centered Example

View a community-centered activity about individual perceptions and beliefs about mathematics in the IRIS Module High-Quality Mathematics Instruction: What Teachers Should Know.

View a community-centered activity about individual perceptions and beliefs about mathematics in the IRIS Module High-Quality Mathematics Instruction: What Teachers Should Know.

Activity

Are the statements about mathematics ability in the boxes below True or False? Read each and click “True” or “False” to find out the answer.

Perceptions and Beliefs Regarding Math

Are the statements about mathematics ability in the boxes below True or False? Read each and click “True” or “False” to find out the answer.

(Close this panel)

After they’ve learned something about individual perceptions and beliefs about mathematics, this community-centered activity will allow students to share something about their own beliefs and how those might influence their teaching practices. Community-centered activities also help students to identify views of their own that might be different from those of their peers, and to decide whether those differences are acceptable. These types of activities are an occasion for students to begin to understand how ideas and misperceptions are socially constructed. By sharing meaningful interactions with one another, they can practice acceptance, tolerance, collaboration, and a shared respect for others.