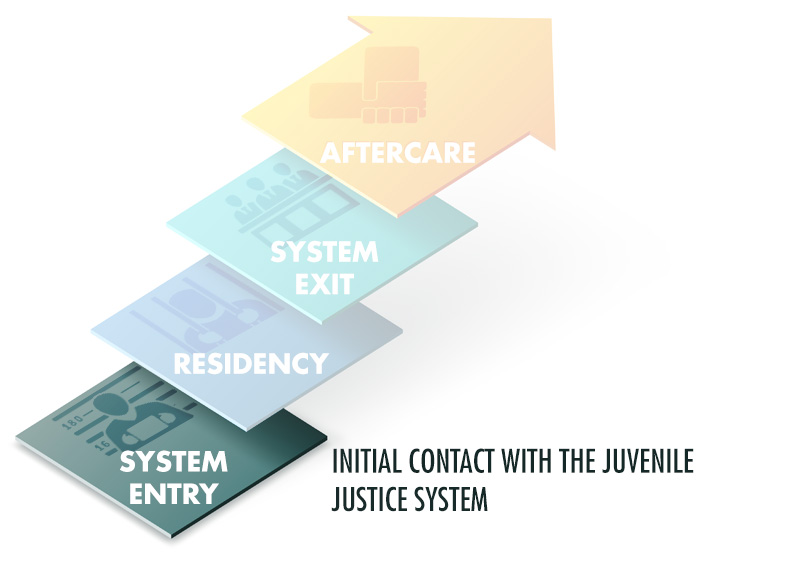

How might transition planning evolve during incarceration?

Page 3: Transition Planning at System Entry

The first transition youth make occurs when they enter the JC facility itself. Typically, on the youth’s first day of incarceration, a facility staff member conducts a lengthy interview to learn more about his or her personal history, including information about his or her educational, employment, and independent living skills, strengths, needs, and goals.

The first transition youth make occurs when they enter the JC facility itself. Typically, on the youth’s first day of incarceration, a facility staff member conducts a lengthy interview to learn more about his or her personal history, including information about his or her educational, employment, and independent living skills, strengths, needs, and goals.

Effective Transition Practices

On this page, we will discuss five of the six effective transition practices that are implemented at system entry.

| Create a Transition Team | Create a Transition Plan | ||

| Establish Quick Records Transfer | Utilize Evidence-Based Practices | ||

| Monitor the Transition Process |

The information gathered at this point will help to determine who should be part of the youth’s transition team, the purpose of which is to determine and oversee the services and supports the youth will receive from the time of system entry through aftercare. Ideally, this team should be led by a transition coordinator or specialist, who typically will be employed by the JC facility. Because the needs of incarcerated youth with disabilities are many and varied, transition teams should include educators, community service providers, juvenile justice officials, the youth him or herself, parents or guardians, and other stakeholders who must communicate and collaborate to help ensure a successful transition. Interagency collaboration—a process in which juvenile justice professionals establish partnerships with personnel from multiple agencies to improve outcomes for students with disabilities—is critical to successful transition planning.

Multidisciplinary Transition Team Members

The members of a given transition team should be selected with the incarcerated youth’s unique needs and goals in mind. Ideally, this team should include the student, a family member or guardian, and relevant juvenile justice personnel (e.g., teachers, probation or parole officer, transition coordinator). In addition to the required team members, other personnel are often needed to address the individual needs of the youth.

| Team member | Role |

| Youth* |

|

| Family member, guardian, or surrogate parent* |

|

| Education representative (e.g., one or more teachers from the facility)* |

|

| Special education teacher or representative* |

|

| A representative of the local school district |

|

| Related service providers (e.g., speech- language therapist) |

|

| Assessment specialist (e.g., school psychologist, reading specialist)* |

|

| Transition coordinator or specialist |

|

| Probation officer |

|

| Mentor |

|

| Workforce development representative or employment service provider |

|

| School counselor |

|

| Social services, foster care representative |

|

| Health and mental health services provider |

|

| Representatives from other community-based organizations (e.g., vocational rehabilitation, social security administration, recreational services) |

|

* Individuals required by IDEA to be in attendance for students with disabilities.

Deanne Unruh discusses the importance of interagency collaboration and provides some strategies that can support youth reentering the community (time: 2:27).

Deanne Unruh, PhD

Principal Investigator, STAY OUT

Co-Director, National Technical Assistance Center on Transition

Associate Research Professor

University of Oregon

Transcript: Deanne Unruh, PhD

When thinking about the reentry process for a young offender coming back into the community, the community’s capacity to serve this youth is very important. One of the critical features is strong interagency collaboration between the schools and juvenile justice services and many of the other agencies, such as mental health, drug and alcohol addiction services that can support the youth in maintaining their positive engagement. What we have found that supports building the community’s capacity for this is developing some interagency collaboration strategies that really support the youth in their reentry project.

A good strategy for helping support interagency collaboration is to develop a strong record-sharing process. This would include both being able to transfer records from a juvenile correctional facility to the home school and being able to share information across agencies. Another key component is educating all partners about your specific agency. For example, we found it beneficial to educate juvenile services workers about [the] Individuals with Disabilities Education Act, helping them understand what are the laws relative to serving youth with disabilities in schools.

On the other side, it’s also been beneficial for us to educate school personnel relative to the juvenile services component. Oftentimes, assistant principals or the registrars or school counselors may be the first point-of-contact for the young offender re-enrolling back into the school system. Having the assistant principals or school counselors know what the procedures and processes are relative to serving a youth in the community by juvenile services is very helpful in breaking down that stigma of serving a young offender for them.

Another key component is initiating regular planning meetings. Oftentimes, these can be quite useful in helping each agency understand what the eligibly requirements are for each of their agencies so the youth can gain access to service at a much quicker rate. Being able to build that interagency collaboration across agencies is very critical for serving young offenders as they come back into their home community.

For Your Information

A transition plan should not be a static document. Student progress toward transition-related goals should be monitored regularly, and changes to the plan should be made as necessary.

The transition team uses the information gathered at system entry to inform the youth’s transition plan (TP), a written document that will be used to guide all transition-related activities. The TP for each youth should be unique, because every youth has specific strengths, interests, and needs. The plan should actively involve the youth, and his or her family when possible, instead of simply being created for the youth.

Leslie LaCroix, a transition specialist, discusses how information is gathered upon entry and used to guide the development of the translation plan (time: 1:42).

Leslie LaCroix, MAT

Transition Specialist, Project RISE

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College

Arizona State University

Transcript: Leslie LaCroix, MAT

When a youth first comes in, they spend three weeks in what we call RAC, reception and counseling. And they go through a whole battery of surveys and assessments, and one of them, of course, is the credit assessment. So those three weeks that the child is in RAC allows the counselors time to plan out the educational trajectory for the child so that they can achieve their goals, hopefully before exiting, or at least accumulate as many credits as possible before exiting.

Counselors have access to the transcripts, and they actually write out a course plan. They map out what core classes has the child taken, what electives are missing. They get input from the youth about what classes they want to take. Some of the kids, if they’re 17 and they have three credits—which happens, unfortunately, a lot—the counselors will do the very best they can to get them caught up on core things—language arts, mathematics, science, things like that—but often, unfortunately, these kids are leaving with only five or six high school credits, and the likelihood of them wanting to go out into the community and finish their diploma is really pretty slim. Most of those kids would prefer to work. We do account for youth voice. The transition plan is their plan. It’s not my plan. It’s their plan, so whatever it is that they say that they are motivated to do that is what we work on in transition.

Under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act of 2004 (IDEA), youth with disabilities should have a transition plan in place by the time they turn 16 (or as early as 14 in some states or if the IEP team deems it necessary). This plan is called an individualized transition plan (ITP) and is a part of their individualized education program (IEP). The youth’s transition goals related to release to the community from the JC setting should be incorporated into the existing ITP.

Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)

Name given in 1990 to the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHA) and used for all reauthorizations of the law that guarantees students with disabilities the right to a free appropriate education in the least-restrictive environment.

Individualized Transition Plan (ITP)

A statement, included in a high-school student’s IEP, outlining the transition services required for coordination and delivery of services as the student nears adulthood.

individualized education program (IEP)

A written plan used to delineate an individual student’s current level of development and his or her learning goals, as well as to specify any accommodations, modifications, and related services that a student might need to attend school and maximize his or her learning.

evidence-based practice (EBP)

Strategy proven to be effective for the majority of students through experimental research studies or large-scale research field studies.

To the greatest extent possible, the transition team should be familiar with and use evidence-based practices (EBPs). These interventions and supports can include general and special education practices, career and technical instruction, behavior management, mental-health treatment, and a variety of specialized supports such as anger management or drug-abuse counseling. Each area has different criteria or requirements for what constitutes an evidence-based practice, something that can make transition planning challenging. The following are examples of reliable, searchable indexes of evidence-based practices that might be applicable for those working with youth in JC settings.

| Area | Examples of websites for EBPs |

|---|---|

| Education | |

| Substance abuse and mental health | |

| Juvenile Justice |

*Logo courtesy Juvenile Justice Information Exchange, Center for Sustainable Journalism, Kennesaw State University

Addressing Key Areas of Transition at System Entry

Recall that transition planning should address the areas of education, employment, and independent living. The ways in which each of these areas are addressed at system entry will be discussed briefly below.

![]()

The transition plan needs to include information about the youth’s current level of educational functioning and his or her educational goals. Youth records (e.g., academic records, IEP) give JC personnel the information they need to evaluate and accommodate the needs of youth as they transition into and out of the juvenile justice system. The educational services the youth receives while incarcerated should support his or her long-term educational goals. For instance, does the youth want to receive a high school diploma or a GED? Does the youth want to pursue post-secondary education or training? Does the youth have a disability?

Key Activities at System Entry

- All education records—including IEPs—are requested from their previous school. The quick and efficient transfer of youth records and related information allows continuity of learning, services, and supports.

- The youth is screened for academic difficulties, including disabilities. The law requires that students with disabilities receive adequate educational supports and accommodations while incarcerated.

- The transition team begins meeting regularly.

- The team outlines in the transition plan the specific evidence-based practices that the youth will receive during incarceration to address his or her educational and behavioral issues. This should include general and special education programming, as well as career and technical instruction or training.

For Your Information

- Educational services might be provided by one of several entities, such as the juvenile corrections facility, the local public school system, private contractors, or a charter school. When both education and security are managed by the juvenile corrections facility, there is generally more communication between the education and security staff, something that can help to streamline the transition planning process.

- The team should consider and respect the student’s cultural beliefs and values. Implementing practices that align with the student’s cultural background and differentiating instruction accordingly can help increase student engagement.

![]()

All youth residing in a JC facility could benefit from some kind of employment training, particularly those over the age of 16. Even those returning to school after release might want to obtain a part-time job. Those who are younger might benefit from learning employment-related skills such as being on time and being reliable.

Key Activities at System Entry

- Staff interview the youth about his or her work experiences and future employment goals.

- Using this information, the transition team develops employment goals for the transition plan.

- The transition team outlines in the transition plan the specific evidence-based practices that the youth will receive during incarceration.

![]()

Independent-living skills address a broad range of functional living skills, from basic social skills to finding a place to live and managing a budget. They also include anger-management skills and physical and emotional wellness.

Key Activities at System Entry

- Staff administer screenings for mental health, emotional, and behavioral difficulties.

- Staff interview the youth about any previous mental health or counseling services he or she has received.

- Using this information, the team identifies the youth’s strengths, needs, and goals and develops independent-living goals for the youth.

- The team outlines in the transition plan the specific evidence-based practices that the youth will receive during incarceration to address his or her mental health, emotional, and behavioral issues.

Carlos

During Carlos’ intake interview, he discusses having a learning disability and receiving special education services. He indicates that he struggles with reading and has difficulty in a number of subject areas. Because Carlos’ educational records have yet to arrive, the interviewer was unaware of Carlos’ learning difficulties. The intake coordinator also asks Carlos about his goals once he is released. Carlos responds that he does not want to return to his home or to his neighborhood.

During Carlos’ intake interview, he discusses having a learning disability and receiving special education services. He indicates that he struggles with reading and has difficulty in a number of subject areas. Because Carlos’ educational records have yet to arrive, the interviewer was unaware of Carlos’ learning difficulties. The intake coordinator also asks Carlos about his goals once he is released. Carlos responds that he does not want to return to his home or to his neighborhood.

Later, as the transition team meets and engages in the transition planning process, Carlos’ strengths and interests are considered in regard to education, employment, and independent-living goals. For example, he expresses an interest in working with his hands and in working with computers. Consequently, the team develops a transition plan that includes goals for earning academic credits and at the same time receiving training on computer diagnosis and repair. Because his reading skills are so low, Carlos will require accommodations in most of his classes, as well as intensive reading instruction. The team also determines that Carlos needs a host of independent-living skills (e.g., budgeting, transportation).