Youth with Disabilities in Juvenile Corrections (Part 2): Transition and Reentry to School and Community

Wrap Up

In the United States, roughly 54,000 youth aged 10–17 reside in juvenile corrections (JC) settings. These are secure facilities where youth remain from a few months to several years following a judge’s determination that they broke the law and are therefore delinquent. Many of these youth have disabilities; the estimates of the percentage of incarcerated youth with disabilities typically range from 30%–60%, with some estimates as high as 85%.

In the United States, roughly 54,000 youth aged 10–17 reside in juvenile corrections (JC) settings. These are secure facilities where youth remain from a few months to several years following a judge’s determination that they broke the law and are therefore delinquent. Many of these youth have disabilities; the estimates of the percentage of incarcerated youth with disabilities typically range from 30%–60%, with some estimates as high as 85%.

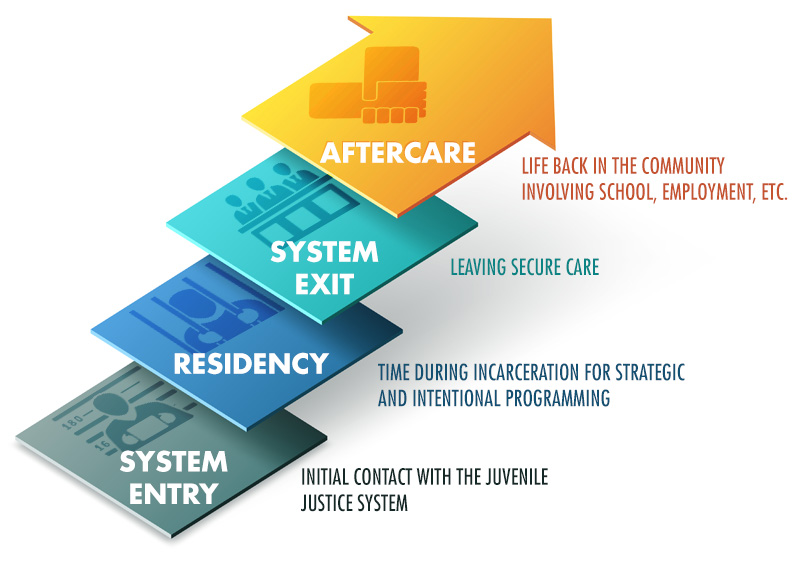

When they become involved in the juvenile justice system, incarcerated youth go through a number of transitions. These include entering the facility, frequently moving from place to place during their stay, and finally returning to the community. Because youth with disabilities, in particular, have a difficult time making the transition back to the home and community setting following incarceration, transition planning should begin as soon as the youth enters the juvenile justice system and continue until (and after) his or her release. Transition planning is carried out by a multidisciplinary transition team consisting of professionals and interested parties and addresses the areas of:

- Education

- Employment

- Independent living

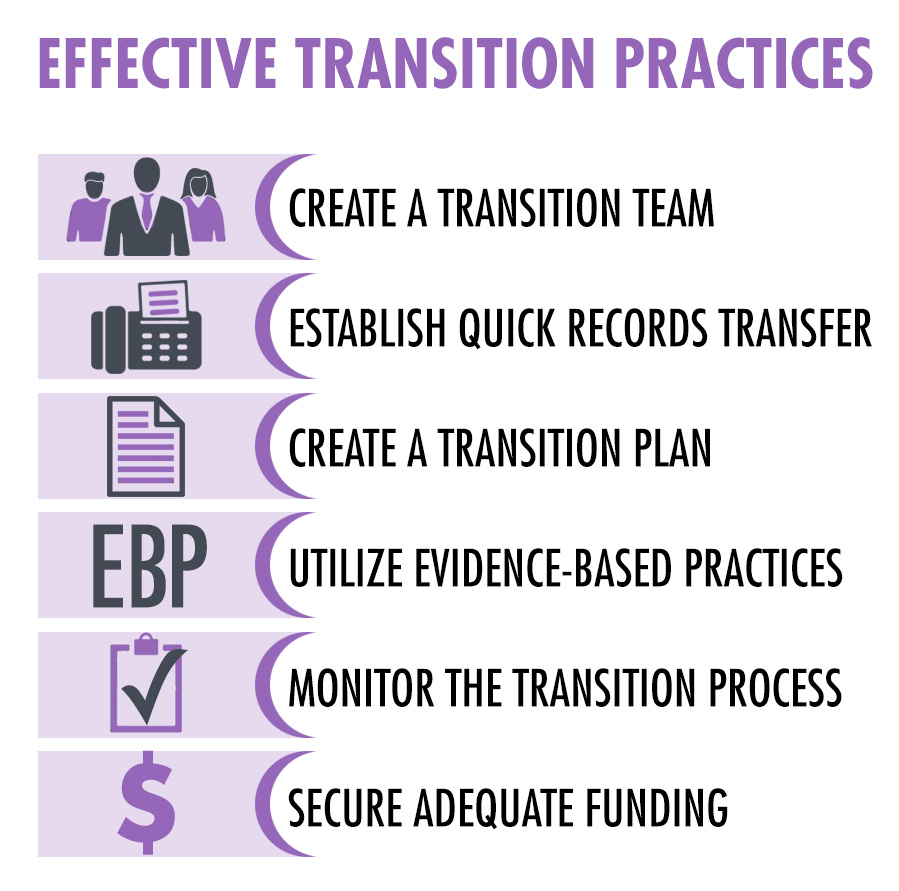

A number of transition practices have been shown to be effective in improving outcomes for incarcerated youth with disabilities. Several model demonstration projects are currently underway whose purpose is to create a replicable, effective transition process for youth with disabilities in the process of returning to their communities. These projects incorporate the effective transition practices listed below.

Carlos

During the year following system exit, Carlos has been fairly successful. During aftercare, his parole officer monitors him and troubleshoots any problems that arise. Additionally, his mentor checks in with him frequently to help keep him on track and to support him when he is facing challenges. As with many youth who exit the system, Carlos has had his ups and downs, as noted in the transition areas below.

During the year following system exit, Carlos has been fairly successful. During aftercare, his parole officer monitors him and troubleshoots any problems that arise. Additionally, his mentor checks in with him frequently to help keep him on track and to support him when he is facing challenges. As with many youth who exit the system, Carlos has had his ups and downs, as noted in the transition areas below.

Education: Carlos’ recent incarceration was a wake-up call. He is now motivated to do well in school and to make something of himself. He is doing better academically and his reading has improved. Even so, he did not pass a couple of classes, something that has put him further behind in earning sufficient credits to graduate. He and the other members of the IEP team are considering options to address this issue.

Employment: Carlos did so well in his apprenticeship that the store owner has hired him to work on Saturdays. In addition, the store owner has become an informal mentor and a positive male role model.

Independent Living: Carlos enjoys living with his grandmother, with whom he gets along well. Although visits with his father have been inconsistent, their relationship has improved. Carlos has managed to stay out of trouble, but this has caused some conflict with members of his former peer group. As a result, Carlos is feeling somewhat socially isolated. Although he has tried several leisure activities, he was not able to maintain any of them due to scheduling, transportation, and financial conflicts. However, he recently started mentoring younger at-risk boys at the neighborhood community center. Though he recognizes that he has a way to go, he wants to help others avoid the mistakes he has made.

Revisiting Initial Thoughts

Think back to your initial responses to the following questions. After working through the resources in this module, do you still agree with your Initial Thoughts? If not, what aspects of your answers would you change?

What is transition planning and why is it important?

How might transition planning evolve during incarceration?

What are some emerging findings regarding successful transition?

When you are ready, proceed to the Assessment section.