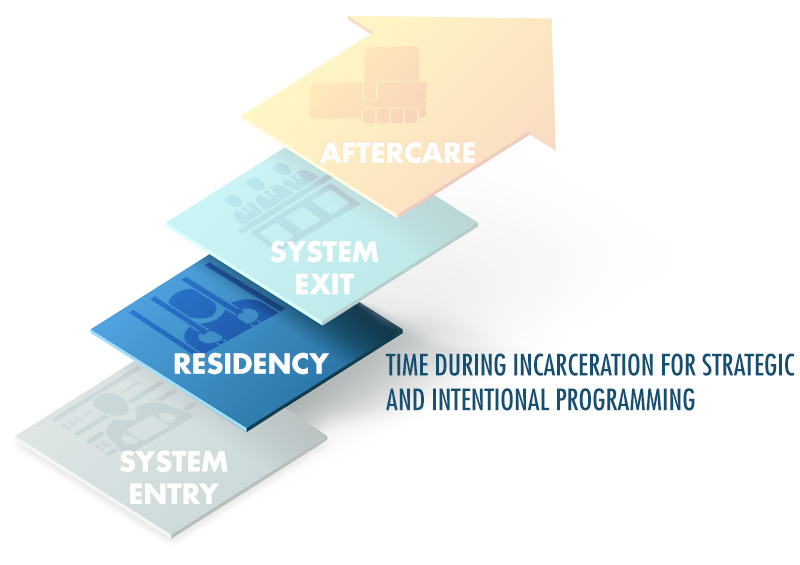

How might transition planning evolve during incarceration?

Page 4: Transition Planning During Residency

A successful transition plan incorporates ongoing, comprehensive assessments of the incarcerated youth’s interests, progress, and challenges. As the youth moves toward the attainment of his or her goals, the transition plan should be adjusted to encourage continued progress. To ensure that this happens, the transition team should meet on a regular basis throughout the duration of the youth’s stay at the JC facility. Because no one person can meet all of a youth’s needs, collaboration and communication are essential elements of effective transition planning. The transition process should also be regularly monitored and the data should be used to make decisions about what is working and what might need to be revised.

A successful transition plan incorporates ongoing, comprehensive assessments of the incarcerated youth’s interests, progress, and challenges. As the youth moves toward the attainment of his or her goals, the transition plan should be adjusted to encourage continued progress. To ensure that this happens, the transition team should meet on a regular basis throughout the duration of the youth’s stay at the JC facility. Because no one person can meet all of a youth’s needs, collaboration and communication are essential elements of effective transition planning. The transition process should also be regularly monitored and the data should be used to make decisions about what is working and what might need to be revised.

Effective Transition Practices

On this page, we will discuss four of the six effective transition practices that are implemented during residency.

| Create a Transition Team | Create a Transition Plan | ||

| Establish Quick Records Transfer | Utilize Evidence-Based Practices |

Addressing Key Areas of Transition During Residency

During a youth’s period of residency, the transition team will need to consider the areas of education, employment, and independent living skills. More information about how those areas can be addressed—in addition to key activities associated with each—can be found below.

![]()

It is crucial that any academic work completed by youth during their period of incarceration should be transferable as credits to the high school they will attend upon their release. A school representative should be on the transition team and take part in developing an appropriate course of study so that the youth in question is able to earn high school credits.

The JC facility should also have the resources available to help youth who wish to pursue post-secondary education or training. Youth will need assistance when the time comes to select appropriate colleges or training programs, complete applications, and secure funding.

Key Activities During Residency

- Staff should provide transition training for all youth, preferably using an evidence-based transition curriculum, to address social skills, decision-making, independent living skills, and workplace skills (e.g., Merging Two Worlds, Expanding the Circle).

- Teachers should provide high-quality, evidence-based instruction for all youth in accordance with their transition goals.

- Staff should collect all education records—including IEPs, credits, courses, and work products/portfolios—in one cumulative file. The transition coordinator should monitor the data in this record (e.g., credit transfer, credit accumulation) and address any issues that may arise.

- For youth with disabilities, teachers should provide evidence-based special education programming in accordance with the youth’s short- and long-term IEP and transition goals. This often includes teaching self-advocacy skills so that youth can identify his or her own needs and request the necessary supports and services.

Leslie LaCroix describes an innovative yet simple method for increasing the number of high school credits youth can earn during their residency (time: 1:27).

Leslie LaCroix, MAT

Transition Specialist, Project RISE

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College

Arizona State University

Transcript: Leslie LaCroix, MAT

Our partnering facility has done a fabulous job in the last couple of years of graduating more kids with diplomas. They’ve realigned their entire calendar. They used to have very long blocks that were about three months long that mimicked more a traditional school, and what they found was that youth were leaving in the middle of these blocks so they were not able to complete their credit before leaving, and it created a lot of chaos, and it lowered the number of diplomas that they were able to issue. So about two and a half years ago, they revised their entire schedule, and now they have five-week blocks with longer classes. So every five weeks, they have two classes, one in the morning for three hours, and one in the afternoon for three hours. They found that with this new model, kids were able to accrue a much higher number of credits. They’ve been able to have so many more kids graduating with diplomas, which is really fabulous for the kids. So then when they leave, they can just focus on vocational aspects instead of having to worry about going back to school. I think there was a little bit of resistance on the part of the teachers at the beginning because the classes are so long, but that was easily remedied. They have more breaks.

![]()

Job training includes those skills specific to the type of employment the youth wishes to pursue (e.g., welding, nursing), as well as skills related to obtaining a job (e.g., filling out an application, taking part in a job interview). Furthermore, youth will require instruction in some of the “soft skills” related to employment—problem-solving, team work, effective communication, interpersonal skills, reliability, and responsibility, among others. The transition plan needs to describe the evidence-based practices and supports the youth requires to find and keep a good job upon reentry.

soft skills

Non-technical personal skills useful for helping an individual to secure and maintain employment. Soft skills include problem-solving and critical thinking, time-management, communication skills, the ability to work well with others, and the importance of projecting a positive attitude in the workplace.

Key Activities During Residency

- Staff should provide job training relevant to the youth’s transition goals for employment.

- Staff should offer instruction relevant to obtaining a job, such as interview skills.

- Staff should provide instruction in workplace soft skills (often included in a transition training curriculum).

![]()

The transition plan must include the services and supports youth will receive to foster their independent living skills. This information provides a foundation for identifying the community supports and services necessary to help the youth live and participate fully in the community at reentry.

Key Activities During Residency

- Professionals should provide interventions or counseling services to address mental health needs, behavior-management skills, and other necessary skills (e.g., parenting skills for those with children).

- Staff should offer instruction in independent living skills (e.g., banking services, nutrition), social skills, and decision-making skills (often included in a transition training curriculum), among others.

Heather Griller Clark and Jean Echternacht describe the primary components of two different transition training curricula, Merging Two Worlds and Expanding the Circle.

Heather Griller Clark, PhD

Co-Principal Investigator, Project RISE,

Mary Lou Fulton Teachers College

Arizona State University

(time: 4:48)

Jean K. Echternacht, EdD

Co-Principal Investigator, MAP

and Institute on Community Integration

University of Minnesota

(time: 1:29)

Transcript: Heather Griller Clark, PhD

I think that another really important component of transition programming is to have a strong transition training curriculum. And there are a number of different transition curriculums out there. Merging Two Worlds is one of them. It was created here in Arizona, and I was somewhat involved in that, and I have been doing training and evaluation of it for a number of years. The strengths within that curriculum you can find in others as well. I think it’s really important that any transition training curriculum focus initially on what the strengths and areas of needs are for the youth. That really gets the individual looking at what is important to them. What do they value? What are their beliefs? And it has a number of different activities around defining those values and those beliefs and how to put on paper what’s important to you.

So that’s really the basis for building a transition plan, because we want to build plans that are relevant to the youth. If you’re building a plan that is just a boilerplate one for every kid that comes in that facility, it’s not going to have value to that individual. They’re not going to buy into it. They’re not going to be invested in it, and probably your outcomes are not going to be great. That’s the hard thing about transition planning, is it has to be individualized for it to work. It’s a really good way for a teacher to steer them towards long-term outcomes and not short-term. A lot of what we see now are our kids are very impulsive, and that’s kind of the nature of this population in general, but it’s all about immediate gratification and immediate results. So this begins a conversation or a dialogue with the student as to what are your long-term goals, and how do you have incremental objectives that will help you reach that long-term goal. If it’s truly individualized then it’s all about them, and they love it and are invested in it right away. So then you move from “Who am I?” to “Where do you want to go?” And that’s when I think career awareness becomes really important.

Many kids that are in juvenile justice facilities really lack an awareness of the world around them. Their experience has been narrow. Their vision is narrow, and so increasing their awareness as to possibilities for different careers, possibilities for the world of work and where it could take you is something that they generally haven’t thought much about. That’s really when you kind of task-analyze or break down the specific objectives or steps you need to take to make your dream job come to fruition. For many kids, they have some lofty goals. They want to be a professional NBA basketball player, and teachers sometimes struggle with how do I turn that into a long-term goal? You can talk about how NBA players get usually recruited from college. They’re not generally recruited off the streets, and so if you’re serious about being in the NBA you need to get yourself to college. Okay, what do you need to do to get to college? And then you task-analyze or walk it back from there and lay out steps for the individual to get from where they currently are to where they need to be. And now that I’ve gotten this job or now that I’ve enrolled in this program that I want to be enrolled in, how do I manage my time, have healthy relationships with co-workers, manage any medication or health insurance? How do I manage other interpersonal relationships in my life, some of those soft-skills and decision making strategies?

Transcript: Jean K. Echternacht, EdD

Our transition curriculum has four different themes. The first theme looks at who am I as a youth, my experience, my background, how do I learn. We work on a variety of skills: decision-making, communication skills, self-advocacy skills. How do you ask for what you need in an appropriate way? Several of those kind of skills that are essential in school and work but are not academic skills. We talk about career skills, career interests, and college and what it takes to be a college student, what it takes to be a good employee, and then going and visiting different sites or having people come in and talk about their college or their worksite and have the students actually practice interview skills. Some of those interview skill questions include things like can I ask if you’ve been adjudicated? They learn which are the questions you don’t have to answer and which you do.

The way we implemented Expanding the Circle in our project was more on a one-to-one basis. When the Check-and-Connect mentor was working with the youth in their preparation for exit or when they’re in that last two-and-a-half to three months, they’re working specifically on skills that seem to be appropriate for that youth.

For Your Information

Typically, when youth reenter their communities, the transition team’s goal is that they should return to their families (e.g., biological parents, grandparents, other relatives, surrogates, or foster families). To facilitate this, communicating with and involving families while a youth is incarcerated can improve the likelihood of a successful transition back into the community and can help also to reduce recidivism. Juvenile corrections staff can involve families by:

- Making available programs for family members, for example training in positive parenting techniques, behavioral management skills, understanding typical youth behavior, and effective communication

- Offering family counseling

- Communicating and treating families with respect—including being sensitive to their cultural and linguistic needs (e.g., providing information in a language that families can understand)—and making certain that they have the opportunity to share their thoughts and concerns

- Including families as active members in the development of the transition plan, as well as accommodating multiple means of communication (e.g., in-person, phone, video conferencing)

Information adapted from NDTAC’s Transition Toolkit 3.0.

Deanne Unruh stresses the importance of including families in the transition planning process (time: 1:10).

Deanne Unruh, PhD

Principal Investigator, STAY OUT

Co-Director, National Technical Assistance Center on Transition

Associate Research Professor

University of Oregon

Transcript: Deanne Unruh, PhD

For the school personnel to work with families is very important. Family involvement is a predictor for post-school success for youth with disabilities and is a critical component for young offenders with disabilities. Oftentimes, when thinking about family for a young offender, the definition of family might be quite broad. It could be the biological family. It could be an intergenerational component of the family. It could be an aunt, uncle, grandmother, or helping identify who is a positive adult within the youth’s life and working with them.

We’ve also found that for youth to be stable within the community that their home environment needs to be stable also. So school personnel might do an assessment of what are the family’s needs. Not that they would provide these services, but they might be a referral source to other types of agencies relative to housing, mental health for family individuals. But I also stress that these agencies need to make sure that the referrals are culturally appropriate and age appropriate.

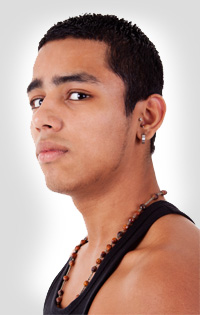

Carlos

Once Carlos’ school records arrive, the team reconvenes. They use the information in his records as well as the assessment data gathered at intake to implement evidence-based instruction, including intensive intervention in reading. The team also uses the information in his school records to determine what credits he has earned and what credits he should work toward during his period of incarceration.

Once Carlos’ school records arrive, the team reconvenes. They use the information in his records as well as the assessment data gathered at intake to implement evidence-based instruction, including intensive intervention in reading. The team also uses the information in his school records to determine what credits he has earned and what credits he should work toward during his period of incarceration.

Meeting on a regular basis, the team monitors Carlos’ progress and revises his transition plan as needed. For example, the team quickly recognizes that Carlos already possesses good social skills—one of the goals in his initial transition plan—and so they decide to place more focus on the soft skills Carlos will likely require if he is to succeed in a work environment (e.g., listening carefully to customers, asking questions when more detail is needed, remaining calm when dealing with an upset client).

Further, the team reviews how Carlos is doing in drug and family counseling. They determine that his drug use was recreational and did not represent a substance abuse issue. Carlos feels that he is learning skills that will help him avoid future drug use. Although he does not plan to live with his father upon release, he acknowledges that he wants to continue to have contact with him. As such, his family counseling programming will focus on improving communication and developing better conflict-resolution skills.