What techniques will help Alexandra and Zach become independent learners, and how can they gain those skills?

Page 4: Self-Monitoring

Self-monitoring is a strategy that teaches students to self-assess their behavior and record the results. Though it does not create new skills or knowledge, self-monitoring does increase or decrease the frequency, intensity, or duration of existing behavior. It also saves teachers time monitoring students’ behavior.

Self-monitoring is a strategy that teaches students to self-assess their behavior and record the results. Though it does not create new skills or knowledge, self-monitoring does increase or decrease the frequency, intensity, or duration of existing behavior. It also saves teachers time monitoring students’ behavior.

Benefits for All Students

Self-monitoring provides more immediate feedback to students than is possible when teachers evaluate the behavior.

Self-monitoring provides more immediate feedback to students than is possible when teachers evaluate the behavior.- The strategy clearly depicts improvement over time in behavior for both the student and the teacher.

- The self-monitoring process engages students.

- Self-monitoring facilitates communication between students and their parent.

- Students can avoid competition because of the individual nature of the strategy.

- Self-monitoring incorporates academic and social skills (e.g., counting, reading, classifying, cooperating).

- The strategy increases students’ awareness of their own behavior.

- Self-monitoring produces positive results.

(Moxley, 1998; Rock, 2005)

Benefits for Students with Disabilities

In addition to the benefits described above, studies on self-monitoring with students with disabilities in inclusive classroom settings have demonstrated positive changes in the following behaviors:

Social behaviors and completion of written classroom work at the high school level

Social behaviors and completion of written classroom work at the high school level- The ability to follow directions in junior high school classes

- Less aggressive behavior

- Academic engagement and fewer disruptive behaviors for elementary-age students

- On-task behavior, less disruptive behavior, and listening skills for grades 7 through 9

- Math fluency

(Gumpel & Shlomit, 2000; Hughes, Copeland, Agran, Wehmeyer, Rodi, & Presley, 2002; McDougall & Brady, 1998; Rock, 2005; Wehmeyer, Yeager, Bolding, Agran, & Hughes, 2003)

Though self-monitoring can be used in many ways for many different behaviors, this module will focus on two of the most common and easiest to use. These are self-monitoring of attention (SMA) and self-monitoring of performance (SMP).

Self-Monitoring of Attention

SMA is great for students who might be easily distracted, get up from their seats, bother other students, or fiddle with objects. The student can monitor the frequency or duration of these behaviors.

Self-Monitoring of Performance

SMP is appropriate for students who need to monitor some aspect of academic performance, such as the rate at which they correctly complete class work or the overall accuracy of their performance. It is especially useful for building fluency.

Alexandra has difficulty paying attention during instruction. Ms. Torri has decided to teach Alexandra the strategy known as self-monitoring of attention.

Alexandra has difficulty paying attention during instruction. Ms. Torri has decided to teach Alexandra the strategy known as self-monitoring of attention.

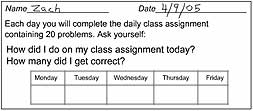

Zach has trouble completing his class assignments, so Ms. Torri has decided to implement self-monitoring of performance with him.

Zach has trouble completing his class assignments, so Ms. Torri has decided to implement self-monitoring of performance with him.

Before Ms. Torri implements these self-monitoring strategies with Alexandra and Zach, she needs to review the five steps in the self-monitoring process.

Steps in Self-Monitoring

Teaching students to self-monitor is a straightforward process. The steps below are the ones teachers should use, and we’ll discuss each of them in turn.

To begin the self-monitoring process, select a behavior for a student to self-monitor. One good way to do this is to remember the acronym SOAP.

To begin the self-monitoring process, select a behavior for a student to self-monitor. One good way to do this is to remember the acronym SOAP.

Specific means that the teacher can tell the student exactly what behavior(s) he or she will self-monitor. Students must be able to determine easily and accurately whether a behavior has occurred. It’s not a good idea to try to self-monitor behaviors like “being good” or “behaving yourself.” Instead, use behaviors like “listening to the teacher” or “doing my work,” which are easy for the student to understand and identify. However, it would be appropriate for a student to self-monitor “talking out” when the teacher is instructing.

Observable means that the student can readily identify the target behavior. For example, the student may not be able to easily observe whether he is “doing better in math,” but he can easily observe whether he got 7 out of 10 problems correct.

Appropriate means that the behavior is a good match for the setting and task. For example, it would not be appropriate for a student to self-monitor “talking out” during a small-group discussion on a topic in which participation is encouraged. However, during a time in which the teacher is instructing, self-monitoring of “talking out” would be appropriate.

Personal means that the behavior is matched to the student’s cognitive and developmental levels. For example, you might expect a seventh-grade student to read independently for one hour, but you would not expect this from a first-grade student.

For Your Information

When students are allowed to help select the behavior to be modified, they are more likely to consider the task important and become more engaged in the self-monitoring process.

Once the target behavior has been identified, the teacher should decide when and where the student should use self-monitoring (e.g., during a 20-minute morning seatwork period). Then the teacher should collect information about the behavior (baseline data) during this setting for several days. She or he can do so in a number of ways, depending on the nature of the target behavior.

This graph, entitled Alexandra’s Attention – Baseline, shows the percentage of time Alexandra is paying attention per day. The vertical axis is labeled “Percent of Time Paying Attention” from 0 to 100 in 10 percentage-point increments. The horizontal axis shows the number of days, from Day 1 to Day 5, in one-day increments. A data point is plotted for each day and the points are connected in a line graph. Alexandra pays attention for the following percentage each day: Day 1–20 percent, Day 2–30 percent, Day 3–20 percent, Day 4–20 percent, and Day 5–30 percent.

- Duration – A measure of the length of time during which the behavior occurs in a given period. This can be gauged by using a stopwatch, egg timer, or hourglass to determine how long a student:

- Stays on task

- Remains in his or her seat

- Frequency – The number of times the behavior occurs. This can be determined by counting the number of times the behavior occurs, as in:

- The number of correctly worked problems

- The number of times the student raised his or her hand instead of talking out of turn

ORIt can also be determined by recording the occurrence of the behavior at the end of a given interval. Such an interval can be signaled by a beep tape (that is, a tape containing beeps or tones at predetermined intervals) or timer. This works well for behaviors such as:

- Listening

- Paying attention

- Staying on task

- Remaining seated

Keep in Mind

Duration and frequency can be used to measure many behaviors. Teachers need to decide how to track behavior based on how often it occurs and on the goal for the behavior. Likewise, teachers should consider what the students’ skills are in terms of self-monitoring.

Once the baseline data are collected, the teacher should graph the results. Collecting baseline data is a crucial step, but one that is quite often skipped. The data allow the teacher and student to compare the behavior prior to and after the implementation of the self-monitoring strategy. The data can also help the teacher to decide whether the targeted behavior is in fact a problem. Once in a while, a teacher will discover that the behavior was not nearly as serious as he or she initially believed it to be.

The next step is to convince the student to cooperate willingly. Remember, the “self” is the active ingredient in self-monitoring. The teacher will need active and willing cooperation from the student if self-monitoring is to be successful. The best way to win cooperation is to address the problem frankly with the student. Talk about how self-monitoring can benefit the student: “Staying in your seat means you don’t lose recess”; “Practicing arithmetic facts each day will help you do better on the test.” Don’t promise the moon. Students are unlikely to respond to exaggerated claims. The key is to be optimistic but realistic.

The next step is to convince the student to cooperate willingly. Remember, the “self” is the active ingredient in self-monitoring. The teacher will need active and willing cooperation from the student if self-monitoring is to be successful. The best way to win cooperation is to address the problem frankly with the student. Talk about how self-monitoring can benefit the student: “Staying in your seat means you don’t lose recess”; “Practicing arithmetic facts each day will help you do better on the test.” Don’t promise the moon. Students are unlikely to respond to exaggerated claims. The key is to be optimistic but realistic.

Review Description

This is a self-monitoring form for Alexandra on 4/10/05. Underneath her name and date is the text, “Ask yourself: ‘Was I paying attention?’” and the following three bullets: in my seat, working on an assignment, listening to the teacher. Below the bullets is the text, “Circle yes or no each time you hear the beep,” and a table numbered 1 through 10 with the options yes or no beside each number. Surrounding the text are Alexandra’s doodles of hearts, a peace sign, a smiley face, and a flower.

Now the teacher is ready to begin teaching the self-monitoring procedures. The process is a simple one that usually takes little time to implement. The teacher explains where and when self-monitoring will be used and teaches the actual procedures used in self-monitoring.

The teacher:

- Defines the identified behavior specifically (e.g., talking to a neighbor) and the student models the desired behavior (e.g., listening to the teacher)

- Models the problem behavior and the target behavior (e.g., talking to a neighbor and listening to the teacher) and lets the student identify which is the desired one

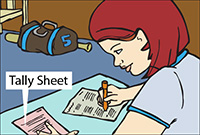

- Explains when and how to record the occurrence of the desired behavior on the self-monitoring form or tally sheet. (Show Example Tally Sheet)

- Role-plays the above self-monitoring procedures with the student

- Specifies when and where the student will self-monitor the behavior

It is important that the student be able to use the procedures effortlessly. Self-monitoring procedures should not be distracting for the student. Rather, they should be almost automatic.

For Your Information

Letting the student personalize the self-monitoring form helps with ownership and makes the process more enjoyable. In addition, tally sheets should be designed to reflect the age, developmental level, and individual needs of the student. SMA (self-monitoring of attention) usually uses cues to remind students to self-assess. For example, a teacher might use an audio tape that contains tones or some other method to signal a time interval. SMP (self-monitoring of performance) usually requires the student to count the occurrence of the behavior.

Now the student is ready to use self-monitoring independently. The first few times the student uses self-monitoring, it is often a good idea for the teacher to remind him or her about using the procedures. The teacher should also check to see that the student is employing the procedures correctly and consistently.

Now the student is ready to use self-monitoring independently. The first few times the student uses self-monitoring, it is often a good idea for the teacher to remind him or her about using the procedures. The teacher should also check to see that the student is employing the procedures correctly and consistently.

When the student begins to self-monitor, he or she will keep track of the identified behavior on the self-monitoring form. The student or the teacher should plot these data on the same graph on which the baseline data are graphed. This comparison allows the teacher to determine whether self-monitoring is effective. It will also help the student to see the improvement in his or her behavior.

The student and teacher should periodically evaluate the student’s progress. If the self-monitoring is effective, the teacher and student should see a marked change in the target behavior in a short time. Booster sessions may be necessary if the behavior deteriorates.

Now that Ms. Torri is familiar with the steps in the self-monitoring process, she is ready to implement this strategy with Alexandra and Zach.

Click on the movie below to see how Ms. Torri implements SMA with Alexandra (time: 2:57).

Transcript: Select a Behavior to Self-Monitor

Narrator: Ms. Torri has decided to implement self-monitoring with Alexandra to help her pay attention in class and focus on her work. Because she’s noticed that Alexandra spends a lot of time out of her seat, Ms. Torri has defined “paying attention” for Alexandra as “in her seat,” “doing her work,” and “listening to the teacher.” Next, Ms. Torri needs to collect baseline data on how often Alexandra pays attention. She observed the behavior during math class for five days and determined that Alexandra spends on average only 25 percent of the class period paying attention. Now that Ms. Torri has determined that Alexandra does indeed have a problem paying attention, she needs to obtain Alexandra’s cooperation to effectively implement the self-monitoring strategy.

Ms. Torri: Alexandra, I wanted to talk with you today about paying attention in class. I’ve noticed that you’re really having problems staying in your seat and focusing on your work lately. But I think that there may be a way to help you with this. I’ve used something with kids just like you and it worked well. I think it would really help you to pay attention better. Do you think you’d like to try it?

Alexandra: I guess.

Narrator: The next step is for Ms. Torri to teach Alexandra the procedures for self-monitoring.

Ms. Torri: Okay, let’s talk about what it means to pay attention. Here are some things that you need to think about to figure out whether or not you’re paying attention: “Was I in my seat, doing my work, and/ or listening to the teacher?” Now, let’s pretend that you’re doing your math practice in the morning. Show me what you look like when you’re paying attention. Good, now tell me what you’re doing.

Alexandra: I’m doing my math problems.

Ms. Torri: Good! That’s paying attention! Now I’m going to show you how to help yourself pay attention. I’m going to play a tape that has some beeps on it. Every time you hear a beep, you should ask yourself, “Was I paying attention?” Now what do you do when you hear a beep?

Alexandra: Ask myself if I was paying attention.

Ms. Torri: That’s right. Then you use the sheet and circle “yes” if you were paying attention and “no” if you were not paying attention.

Narrator: Ms. Torri role-plays with Alexandra. First, Ms. Torri pretends to be the student and then they switch roles. The last thing Ms. Torri needs to do is establish when and where the student will self-monitor the behavior.

Ms. Torri: Now, Alexandra, tomorrow when you do your math work, we will use the beeps to help you do your work. We will do it just like we practiced today.

Narrator: Alexandra self-monitors her attention for several days.

Ms. Torri: Okay, Alexandra, remember to listen to the beeps. Every time you hear a beep, ask yourself, “Was I paying attention?” and mark your sheet.

Narrator: At the end of each math class, Ms. Torri and Alexandra graph how often she was paying attention.

(Close this panel)

Activity

SMP with Zach

Zach hates math. He’d much rather think about riding his bike than practice math, which in turn means that his scores on daily class assignments are poor. He knows his math facts fairly well, but because his assignments are rarely complete he almost never makes passing scores on them.

Click the pictures below to help Ms. Torri implement self-monitoring with Zach to improve his math performance. Bob Reid, PhD, University of Nebraska, an expert in this field, will offer feedback for each step.

Step 1 |

Step 2 |

Step 3 |

Step 4 |

Step 5 |

|

Step 1

- Number of problems completed

- Number (or percent) of problems correct

- Trying my best

Step 2

Step 3

- A. Zach, I want to talk to you about your math. I know that you don’t like math and that you’ve had some problems on your class assignments. Yesterday you refused to work on it at all.

- B. I think one problem is that you need to practice your facts more. You know that old saying “Practice makes perfect.” Well it’s true for math.

- C. I know a way to help you practice more. I used it with another student last year and now he always made an A on his test and so can you. How about it?

Step 4

Step 5