What techniques will help Alexandra and Zach become independent learners, and how can they gain those skills?

Page 5: Self-Instruction

Another strategy associated with self-regulation is self-instruction, also referred to as self-talk or self-statements, in which students learn to talk themselves through a task or activity. Young children who talk themselves through the shoe-tying process or a medical student who mentally rehearses the procedural steps while engaged in an injury evaluation are using self-instruction, which uses language to self-regulate behavior. Self-instruction interventions involve the use of self-induced statements to direct or control behavior.

Another strategy associated with self-regulation is self-instruction, also referred to as self-talk or self-statements, in which students learn to talk themselves through a task or activity. Young children who talk themselves through the shoe-tying process or a medical student who mentally rehearses the procedural steps while engaged in an injury evaluation are using self-instruction, which uses language to self-regulate behavior. Self-instruction interventions involve the use of self-induced statements to direct or control behavior.

Listen to Dr. Reid explain why a teacher would want to teach students to use self-instruction (time: 0:30).

Transcript: Robert Reid, PhD

Self-instruction strategies are both powerful and flexible, and they have a well-demonstrated record of effectiveness. Self-instruction strategies can help a student perform difficult tasks, cue them to employ a strategy, or help them remember the steps in a task. Self-instructions can also work on motivational processes and help students deal with stressful situations. Many times teachers will incorporate self-instructions to deal with coping or continuing a task that is difficult.

The Advantages of Self-Instruction

When using self-regulation, teachers may find it beneficial to incorporate components of self-instruction because it:

- Utilizes teachers’ time efficiently

- Provides students with an element of control over their learning

- Requires a minimal amount of time to maintain skills once they are developed

Self-instruction strategies are powerful, flexible, and potentially quite effective. The table below identifies some types of self-instruction. A student may use one of these or a combination. Click the icons below to hear a student using each type of self-instruction.

| Type of Self-instruction | Purpose | Example |

| Problem definition |

Defines the nature and demands of a task “What am I supposed to be doing? Solving these problems. I need my protractor and ruler.” |

|

| Focusing attention/ planning |

Increases attention to a task or to the generation of plans “Am I focusing on the teacher? Did I understand what she just said? Okay, now I have to do six word problems by the end of the period. I need to finish one problem every five minutes to get that done.” |

|

| Strategy |

Explains how to engage and use a strategy “OK, what’s the order for this equation: 2 |

|

| Self-evaluation |

Promotes error detection and correction “Does this answer make sense? Wait a minute…If just one side of this quadrangle is 32 cm, then the whole perimeter can’t be only 35 cm. No, it can’t be right. I need to fix it.” |

|

| Coping |

Teaches how to deal with difficult situations or failures “This is a difficult math equation, and I’m feeling overwhelmed. Just take a deep breath…one step at a time. If I break it down to smaller steps, it won’t be as difficult.” |

|

| Self-reinforcement |

Rewards oneself for accomplishments “Yes! I stayed on task and completed my work, so I’m going to read a Batman comic book when I get home.” |

Students with disabilities approach learning differently than do children without disabilities. Listen to Karen Harris, a researcher from Vanderbilt University, as she talks about research she has conducted where these differences are obvious.

Karen Harris, PhD

Professor and Currey-Ingram Chair

of Special Education

Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN

Differences in Self-Instruction

Karen Harris discusses self-instruction for children with and without learning difficulties (time: 1:49).

The Little Professor

Karen Harris tells a story about a young student with learning difficulties from her study who used self-instruction to calm himself down and remain motivated to complete a frustrating task (time: 1:39).

Transcript: Karen Harris, PhD

Differences in Self-Instruction

Years ago, we were doing a research study that involved having children in kindergarten and first grade do wood-form board puzzles that were actually doable by three- and four-year-old children. We wanted to observe their puzzle-solving strategies and their self-speech or self-instructions while they worked. We looked at both normally achieving children and we looked at children with early and fairly severe language and learning problems. We found very, very large differences between the way these groups of children, in general, approached the puzzle task. The normally achieving children, they usually began by organizing the task: turning the pieces right side up, orienting them, and so forth. And they did talk to themselves out loud. Self-speech is still quite normal at this age, and they felt pretty free to talk while they worked. With this group of normally achieving children, over 85% of their speech was task relevant. They would say things to themselves like, “I need to figure out what this puzzle’s going to be. I need a square shape. I need a green piece.” And they would work through the puzzle. And they would often also reward themselves: “I’m getting it! I’m going to get this.” And they would also say, “Oh, this isn’t really all that hard. This is an easy puzzle.”

And when we worked with the young children with learning difficulties, we found a very different pattern of behavior. These children almost never approached the puzzle systematically. They left pieces upside down. The number-one step taken by almost every child in this group was to grab a piece at random and just use trial and error to try and stick it in the puzzle. In terms of their self-speech or self-statements or self-instructions—all of those meaning the same thing—we had a very dissimilar pattern. About 83% of their speech was off-task and not related to the puzzle or dealing with the challenge of doing the puzzle whatsoever. We had one little boy who sang a song through the whole thing, “Going on a Trip to Idaho.” We had one little girl who talked to herself about Brownies and what they were going to be doing at Brownies.

Transcript: Karen Harris, PhD

The Little Professor

Then in came a little boy who—you just have to picture it—must have been school picture day: crew cut, black glasses, a suit with jacket, bowtie, trousers, and his shoes were so shined that you could see his face in them. He was absolutely adorable, and I instantly nicknamed him “the little professor.” But when he sat down to work, he earned that title even further. I left him, went to do my paperwork, and unlike all the students before him, he looked at the puzzle, but like everyone else, he picked up a single piece and began trying to randomly stick it in. He started to get frustrated, though, and all of a sudden from the other side of the room I see him cross one arm over the other, take a deep breath, push himself back from the table a good couple of feet, and then in a singsong voice say, “I’m not going to get mad. Mad makes me do bad.” He then re-approached the puzzle. He was calm, and he began picking up pieces. He actually turned a few over. He began to get in some of the outside pieces. However, he again got frustrated with the puzzle, and he was not using most of the puzzle-solving strategies, and he again crossed one arm over the other, took a deep breath, pushed away from the table, and in a singsong voice said, “I am not going to get mad. Mad makes me do bad.” Then again he approached the puzzle. Compared to every other child in his group, he worked at the puzzle longer, he got in more pieces. Although no child in this group got all of the puzzle together that was doable, this child did get more pieces than any other child in this group.

Self-Instruction Steps

The ultimate goal of teaching self-instruction is for students to progress from the use of modeled, overt self-statements (i.e., talking aloud to oneself) to covert, internalized speech. Self-instruction can be taught using a simple four-step process. Click on each link to view detailed information about the individual steps in the table below.

| Steps in Self-Instruction | |

| Step 1 | Discuss the importance of what we say to ourselves |

| Step 2 | Develop appropriate self-statements |

| Step 3 | Model and discuss how and when to use self-statements |

| Step 4 | Practice the use of self-statements |

Step 1: Discuss the importance of what we say to ourselves

Students need to know why self-instruction is important. A teacher can explain this concept and offer examples of both positive and negative types of self-talk, discussing the effect of each on a student’s performance.

Example

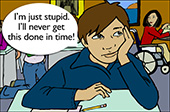

As Zach sits working on his math assignment, Ms. Torri hears him say, “I’m just stupid. I’ll never get this done in time.”

As Zach sits working on his math assignment, Ms. Torri hears him say, “I’m just stupid. I’ll never get this done in time.”

She sits next to Zach and reminds him that when they work the problems together, he is able to complete them, which indicates that he is not stupid. She tells him that saying negative things to himself can cause him to do poorly on assignments. Similarly, making encouraging comments to himself would be more helpful and would have a positive effect on his assignments.

Step 2: Develop appropriate self-statements

Keep in Mind

- It is important to keep the statements at the student’s level.

- Self-generated statements are typically the most powerful for students.

- Depending on the situation, the focus can be on areas related to that situation, with possible self-statements generated for each area.

Example

Ms. Torri and Zach decide that there are four areas in which self-instruction would be helpful: getting started on the assignment, staying on task, coping with difficulties, and giving himself reinforcement. Together, they come up with a list of self-statements for each of these areas.

| Getting started | Staying on task | Coping with difficulties | Giving reinforcement |

|

|

|

|

Step 3: Model and discuss how and when to use self-statements

In this step, the teacher suggests instances in which it would be appropriate to use the generated self-statements and explains to the student how to engage in self-instruction. The teacher then models the self-instruction process, letting the student hear the words she uses to talk herself through a situation.

Example

Ms. Torri tells Zach, “First, we need to think about what you can say when you get ready to do math. Remember that it needs to be positive to help you get through the work. If I’m worried that the work is too difficult, sometimes I like to tell myself, ‘This isn’t that hard. I know I can do it.’ That really helps me. If I can feel myself getting nervous or stressed, sometimes I tell myself ‘Just settle down. Everything’s going to be okay.’ “

Ms. Torri tells Zach, “First, we need to think about what you can say when you get ready to do math. Remember that it needs to be positive to help you get through the work. If I’m worried that the work is too difficult, sometimes I like to tell myself, ‘This isn’t that hard. I know I can do it.’ That really helps me. If I can feel myself getting nervous or stressed, sometimes I tell myself ‘Just settle down. Everything’s going to be okay.’ “

Ms. Torri then acts out several situations, modeling self-instruction for Zach.

Step 4: Practice the use of self-statements

BODAfter the teacher has modeled the use of self-statements, it is the student’s turn to practice. The student should have the opportunity to use the self-statements in a variety of practice situations in order to ensure the acquisition of this skill before she or he is expected to use it independently.

Example

Students who are allowed to help select the behavior to be modified are more likely to consider the task important and become more engaged in the self-monitoring process.

Students who are allowed to help select the behavior to be modified are more likely to consider the task important and become more engaged in the self-monitoring process.

Keep in Mind

The last two self-instruction steps can be combined so that the teacher and the student work collaboratively to model and practice self-statements.

Keep in Mind

Self-instruction alone is useless if the student cannot perform the designated academic or behavioral skill. Be sure that your students are capable of doing the tasks you are requesting.

To use self-instruction successfully, the student must understand why the self-statements are useful. Self-statements should be developmentally appropriate and meaningful to the student.

Activity

Using Self-Instructions

Use the knowledge you’ve gained from this page to answer the following questions.

-

One of your students is always the first one to complete assignments and turn in her tests. Although she is at or above grade level in all academic areas, she rarely gets more than 65% of her problems correct. You suspect that she is getting careless with her work. Which type of self-instructions would be appropriate for her and why?

Click here for one possibility.One Possibility

Self-evaluation statements are used for error detection and correction. Self-evaluation statements could help your student determine whether she is working carefully, whether her work is accurate, and how to correct any mistakes that she finds.

- One of your students refuses to continue reading when he comes across a difficult word. Which type of self-instruction would be appropriate for him and why?

Click here for one possibility.One Possibility

It might be helpful to teach coping self-statements to this student. Coping self-statements are used by students to deal with difficult situations or failures and can help him or her to complete hard or frustrating tasks.

- As you pass out a quiz, you hear one of your students say, “I hate quizzes.” What action could you take to resolve this?

Click here for one possibility.One Possibility

You might want to sit with her and discuss the impact of what she says to herself and the importance of positive self-statements. A next step might be to help her develop possible positive statements she can use instead of negative self-talk.

- You have been working on the use of positive self-instructions with one of your students. You have discussed, developed, and modeled the appropriate use of self-statements with her. After you have gone through this, she responds by rolling her eyes and saying, “Okay, I got it.” What is your next step?

Click here for one possibility.One Possibility

Give her some hypothetical scenarios and suggest that it is her turn to practice using self-instructions. Be sure to give her feedback as she practices to help her improve her self-communication.