How can teachers effectively implement RTI for mathematics?

Page 10: Implementation at East High School

Did You Know?

![]() Principals and all school staff must keep in mind that the adoption and complete implementation of RTI requires a change in existing school processes and is a long-term commitment, usually three to five years.

Principals and all school staff must keep in mind that the adoption and complete implementation of RTI requires a change in existing school processes and is a long-term commitment, usually three to five years.

In the Challenge, you learned that for the past two years, the teachers at East High School have been implementing high-quality mathematics instruction in the general education classroom. Although they did see an improvement in student performance, they noted that many students continue to struggle. The staff at East High School have decided to adopt the RTI framework to address the needs of struggling students. Read on to discover how they implement the features of RTI, which aligns with the procedures outlined in the East High School RTI Guidelines. To review these procedures, click the link below.

Universal Screening

To identify students who need intervention, the RTI team at East High School review the students’ scores on last year’s standardized tests, as well as their recent academic records. Based on these data, twenty-percent were identified as in need of academic support in mathematics. Additionally, at the beginning of the school year the teachers administered a universal screening measure to determine whether students are meeting grade-level benchmarks, to verify whether those identified by the standardized test scores actually need intervention, and to identify other struggling students. Through this process, they found numerous additional students—many of them new to the district—who might benefit from support. They administer the universal screening two more times throughout the year: mid-year and again at the end of the year. Two of the students identified among those needing additional academic support were Grayson, who will receive supplemental support at Tier 2, and Imani, who will receive intensive, individualized support through special education services.

High-Quality Instruction

Grayson and Imani are both taking Algebra 1. During the 50-minute course, the teachers use a standards-based mathematics curriculum as well as evidence-based practices such as explicit, systematic instruction; visual representations; schema instruction; and metacognitive strategies. The teachers also employ effective classroom practices like encouraging student discussion.

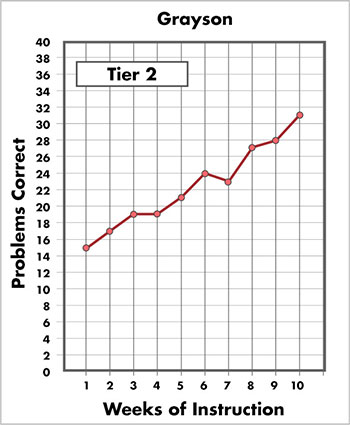

Grayson

In addition to Algebra I core instruction, Grayson receives supplemental intervention in a Tier 2 intervention classroom. The students in this classroom are divided into three groups based on their needs and instruction is led by a highly trained interventionist. This instruction aligns with the core instruction and targets the algebra skills with which he is struggling. Providing Tier 2 intervention that aligns with his core instruction and targets his algebra skill deficits— rather than simply providing remedial instruction on unrelated foundational mathematics skills—will help him master Algebra I content.

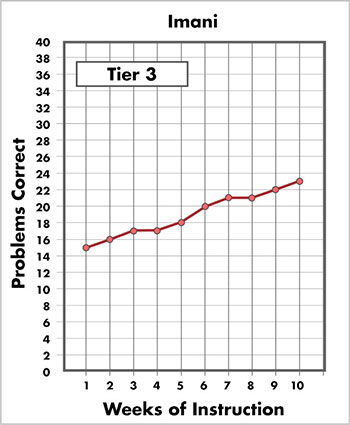

Imani

In addition to Algebra I core instruction, Imani receives Tier 3 intervention. The special education teacher provides intensive, individualized support to Imani and two other students during this intervention time. This individualized instruction targets the algebra skills with which Imani is struggling, rather than foundational skills that she has not mastered.

Brad Witzel discusses the benefits of creating a flextime during the school day to provide instructional interventions. Next, David Allsopp discusses the advantages of scheduling by first taking into account the needs of students who need additional instructional support.

David Allsopp, PhD

Assistant Dean for Education and Partnerships

University of South Florida

(time: 1:01)

Transcript: Brad Witzel, PhD

Structure is an issue when it comes to interventions. Many high schools and middle schools where I’ve had the privilege of working have built in something called a flextime. Initially, this flextime would allow for extracurricular work, as well as academic supports. So a flextime allows for you to do band work during the middle of the day and get tutoring from another. So these flextimes are frequent, and they allow for Tier 2 and Tier 3 intervention times. Students could be assigned a specific intervention during this time. If the intervention is no longer needed, the student could transition to a different setting or take on an extracurricular. Likewise, if a more-intensive intervention is needed then the student could transition into that setting.

This flextime approach may sound ideal for students with academic needs, but there’s even more potential to it. In a large setting like most high schools, the availability of most teachers during this flextime allows for students on different tracks and different needs to receive help even on specific assignments. So during flextime in one room, I might go down the hall to a Tier 2 interventionist. She has eight students who are assigned to her during flextime, and they’re working specifically on a mathematics need. If I look across the hall, there’s 15 students flocked in an AP Physics class getting extra test preparations. Some students will gather in groups to do studying. Other ones will go to a library. So one way to handle this notion of what to do for students who need more support or less support when we have a rigid schedule is to set in a flextime that is not as rigid.

There is an alternative of course. If an intervention takes the role during normal class time, such as second block, there’s little that can be done to make major changes in the student’s schedule during a semester or quarter. Of course, in these situations we ask intervention settings to be flexible enough to provide varied levels of support so that the student can get scaffolds and become successfully independent.

The hardest thing about a flextime is how much time can be devoted to that with such needs during the school day. Because anytime you add this in, you’re taken away from something else. So when you have a flextime in there, there needs to be an agreement that we’re taken away five minutes from every other class so that we can create a 35-minute flextime. This flextime will allow for Tier 2 and Tier 3 interventions to occur. I also worry when you don’t have a flextime and you take them out of things that they may enjoy. So now I have a child who struggles in literacy and mathematics. So they’re going to be getting two extra hours for intervention a day. Well, goodbye, band, goodbye art, goodbye anything that may help them see the bigger picture of life.

In a multi-tiered system of supports, that doesn’t mean we’re just helping out the students who are struggling. I may have advancement in enrichment or acceleration options that could happen during that flextime. So if I have a student who is on a highly gifted measure, I don’t need to say, “Well then you go have a free time during flextime.” No it’s, “You are assigned to this room during that time where you’re going to be working on, for example, engineering mechanisms, and you’ll be creating these new robotic ideas.” So again I like the idea of a flextime, but you know you’re sacrificing something for it.

Transcript: David Allsopp, PhD

The issue of scheduling sounds like a very mundane and basic idea. I was fortunate to work with some folks in several different states at the secondary level. What they thought helped the most is scheduling based on student need first. If targeted, it considers them first and then everybody else. I think if principals and teacher leaders are up front thinking about how these schedules need to play out and then build around that, that’s really important, as opposed to this is a student’s schedule. He’s got an elective in first period. That’s where we’re going to do this. Or he’s got an elective in fifth period. So we’re going to do that. Well, that may not necessarily be the most advantageous way for a student to receive supplemental instruction. It certainly may not be connected to what’s happening in the core course they’re supposedly getting supplemental instruction on.

Progress Monitoring

The Tier 2 instructors conduct progress monitoring with their students every two weeks. The special education teachers conduct progress monitoring more frequently, typically once per week. Following are the results for Grayson and Imani after 10 weeks into the semester.

Data-Based Decisions

At the end of 10 weeks of progress monitoring, the RTI team (which includes the interventionist) meet to review the data for the students receiving additional support. As they do so, they consider both slope and performance level.

Computation Criteria

Benchmark: 34 Slope: 1.15

Grayson’s Data

Performance Level = 29.5

Slope = 1.78

Imani’s Data

Performance Level = 22.5

Slope = 0.67

The table below displays the data-based decisions the team made in regard to Grayson and Imani.

| Student | Does Performance Level Meet Criteria? | Does Slope Meet Criteria? | Data-Based Decision |

| Grayson | No | Yes | Based on the slope of his data, Grayson is making progress. However, his performance level data indicate that he has not yet performing at the expected level. For this reason, the RTI team decides that Grayson should continue to receive Tier 2 intervention. |

| Imani | No | No | Imani’s data indicate that she is not responding adequately to intervention. Therefore, the RTI team suggests that the teacher needs to increase the intensity of the intervention. |

Fidelity of Implementation

East High School has gradually been implementing fidelity checks as they slowly implement RTI. At this point, they are focused on two key areas in regard to implementation fidelity: high-quality instruction at each level of instruction and the administration of progress monitoring measures. This monitoring consists of the RTI coordinator observing the teachers’ instruction and their progress monitoring procedures a minimum of two times per semester.

During the fidelity checks, the RTI coordinator observes that, for the most part, teachers are implementing the standards-based curriculum and evidence-based practices. Fidelity checks of progress monitoring procedures revealed that most Tier 3 teachers are administering progress monitoring probes correctly and at the specified times, but many of the Tier 2 interventionists are inconsistent with their administration procedures. These interventionists will receive ongoing coaching and support to address these issues.

If you would like to learn more about fidelity of implementation, we encourage you to take a look at the following IRIS Module: