What is RTI for mathematics?

Page 4: Instruction

Effective instruction is a cornerstone of the RTI framework. As we discussed earlier, many but not all students who receive high-quality core instruction will succeed in the general education classroom. When teachers implement high-quality instruction at the primary level, inadequate instruction can be ruled out as a reason for students’ poor mathematics performance. Students who do not respond to this instruction should receive more intensive supports. Read on to find out more about high-quality instruction and how instruction is intensified at each of the three tiers of support.

Effective instruction is a cornerstone of the RTI framework. As we discussed earlier, many but not all students who receive high-quality core instruction will succeed in the general education classroom. When teachers implement high-quality instruction at the primary level, inadequate instruction can be ruled out as a reason for students’ poor mathematics performance. Students who do not respond to this instruction should receive more intensive supports. Read on to find out more about high-quality instruction and how instruction is intensified at each of the three tiers of support.

High-Quality Instruction

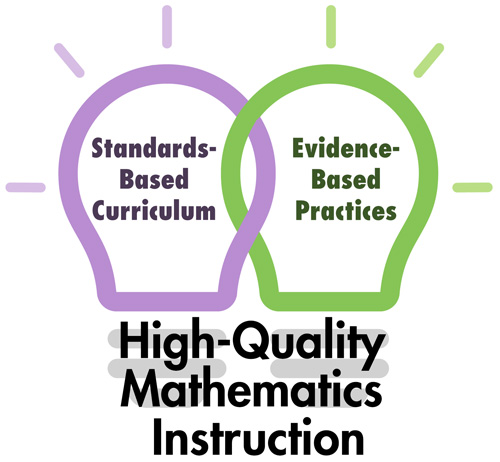

A key feature of RTI mathematics is high-quality instruction. High-quality mathematics instruction involves the combined implementation of:

Standards-based curriculum: The content and skills believed to be important for students to learn. Many states have adopted the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSSM), which are composed of Mathematical Practices and grade-level standards. Additionally, the CCSSM:

Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSSM)

An educational initiative originally sponsored by the National Governors Association designed to create consistent educational standards for mathematics to prepare students across the United States either for college or for post-secondary employment.

- Build upon the strengths of current state standards

- Are informed by instructional practices used in other top-performing countries, so that all students are prepared to succeed in our global economy and society

- Are evidence-based

- Are aligned with college and work expectations

- Are clear, comprehensible, and consistent

- Embrace rigorous content and require the application of knowledge through higher-order skills

- Encourage the use of real-world problems

Evidence-based practices (EBPs): Strategies or practices proven through research to be effective for teaching mathematical concepts and procedures. The use of EBPs is mandated by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). These federal laws require teachers to use, to the greatest extent possible, academic and behavioral practices and programs grounded in scientifically based research. Beyond the issue of legal obligation, however, is the fact that EBPs significantly increase the prospects of student achievement and learning. Among the benefits of using EBPs:

scientifically based research

Research that uses a rigorous and systematic design and high-quality data analyses, and that is published in a peer-reviewed journal.

- Increased likelihood of positive student mathematics outcomes

- Increased accountability because there are data to back up the selection of a practice or program, which in turn facilitates support from administrators, parents, and others

- Less wasted time and fewer wasted resources because educators start off with an effective practice or program rather than attempting to select one through trial and error

- Increased likelihood of being responsive to learners’ needs

- Higher probability of convincing students to try a practice or program because there is evidence that it works

For Your Information

To implement high-quality instruction, teachers need to create a classroom environment conducive to learning. They can accomplish this by establishing a comprehensive behavior management plan that clearly outlines rules and procedures. They should hold high expectations for all students and use a range of instructional strategies and supports. Further, teachers are more likely to create successful learning experiences when they consider factors related to working with diverse students, such as:

- Cultural diversity: Instruction might be confusing to students if their cultural experiences or background knowledge are different from or inconsistent with those of their teacher.

- Linguistic diversity: Mastering academic content might be difficult for students who are not proficient in English.

- Students with exceptionalities: In the event that a disability affects a student’s learning, the teacher might need to make instructional adjustments to help that student to succeed. Similarly, gifted students might require different instructional opportunities like enrichment activities or accelerated learning.

- Socioeconomic diversity: Students might not have access to additional educational resources and supports outside of school.

Increasingly Intensive Levels of Support

All students receive core instruction in the general education classroom, also referred to as Tier 1. Those who do not respond adequately to this instruction receive supplemental support at Tier 2. The small percentage of students who continue to struggle after receiving supplemental support might require more intensive, individualized support at Tier 3.

Tier 1: Core Instruction

Instruction at the primary level, or Tier 1, refers to the high-quality core mathematics instruction (described above) that all students receive in the general education classroom for 45–90 minutes each day. This might be provided as whole-group instruction or through the use of flexible grouping strategies, for instance cooperative learning groups, paired instruction, or independent practice. A few of the evidence-based strategies that can be used to teach mathematics at this level of support can be found in the box below.

| Evidence-Based Practice | Definition |

| Explicit, systematic instruction | This strategy involves teaching a specific skill or concept in a highly structured and carefully sequenced manner. |

| Visual representations | This strategy involves creating an accurate representation of the mathematical quantities and relationships described in the problem, sometimes referred to as a schematic representation or schematic diagram. |

| Schema instruction | This strategy involves teaching students the underlying structure, or schema, of word problems and giving them a method for solving that problem type. |

| Metacognitive strategies | These strategies enable students to become aware of how they think when solving mathematics problems. More specifically, metacognitive strategies help students learn to plan, monitor, and modify their mathematical problem-solving approach. |

Approximately 80% of all students are expected to respond to Tier 1, or core instruction. Those who do not respond—as indicated by progress monitoring data—receive supplemental instruction at Tier 2.

More information about high-quality mathematics instruction and evidence-based practices that can be implemented at the primary level can be found in the IRIS Module:

Tier 2: Supplemental Intervention

In addition to core instruction, students not making adequate progress at Tier 1—approximately 15% of the class—receive supplemental instruction that aligns with that core instruction. Typically, in elementary schools a standard protocol is used to provide this additional instruction, which makes it easier to ensure accurate implementation or fidelity, assuming that school personnel receive adequate training and ongoing support. Likewise, in middle and high schools, a standard protocol might be used; however, many of these schools choose instead to implement a problem-solving approach.

standard protocol

A validated intervention, selected by the school (often for the secondary intervention level), to improve the academic skills of its struggling students.

problem-solving approach

An approach which assumes that each student will respond to an intervention differently and thus warrants an individually tailored, evidence-based intervention. Additionally, by using this approach, educators can group students with similar needs to provide small-group instruction.

Supplemental, or Tier 2, intervention is delivered either by the classroom general education teacher or another trained educational professional like a mathematics interventionist or mathematics coach. The specific details of this delivery varies for elementary and middle and high school.

| Group Size | Length of Intervention | |

| Elementary | 3–5 students |

|

| Middle and High School | Up to 15 students |

|

Brad Witzel discusses the importance of not ending an intervention too soon as well as of providing intervention that meets the needs of individual students (time: 1:27).

Brad Witzel, PhD

Professor of Special Education

Winthrop University

Transcript: Brad Witzel, PhD

Most interventions have a beginning and ending. Some are designed for four weeks; others are designed for eight weeks. There really is no magic time that an intervention is needed for a specific student to catch on. Some students need to have longer interventions than others. They may even come in a group of eight, maybe brought in for a Tier 2 intervention, and they have the same general content need. However, Student A needs a lot more time to establish that intervention and make sense of it. Don’t set up intervention times that are designed for real short durations. If you set up an eight-week intervention time, make sure that you have some extra weeks set aside in there so the student can continue with that intervention.

Therefore, you’ve got to be flexible enough within this group to work with different student needs. I think some people hear that you’ve only got eight students in the class and they go, “Oh, what a dream life that would be.” But you really don’t have a group of eight students. You have eight individuals going through that intervention. Some schools will immediately turn to computers, but I don’t think that’s exactly the answer yet. I still want to see a lot of teacher-student interaction and forced activity by the student. Because we don’t just want them to obtain and answer questions. We want them to truly have reasoning in mathematics, and at this point it’s hard to establish reasoning on a computer interface.

For Your Information

Because scheduling at the middle and high school levels is complex, the RTI team should carefully consider how to provide supplemental instruction in a way that makes sense given their school’s resources. Among the issues the team might wish to consider:

- When to provide supplemental support: Instead of an elective, during a free time, before or after school, within the core instruction class.

- How to create additional time for supplemental support: Shaving five minutes off of each period, reducing transition times between classes.

- How students will earn credits: Will they receive credits for supplemental support classes, and, if so, how many? Will they be able to accrue enough credits to graduate on time?

For students who require additional instructional support, David Allsopp suggests considering the students’ needs and being planful. By doing so, school personnel can better ensure that students get the support they need while at the same time taking required courses. He also discusses making sure that the supplemental intervention is appropriate and adequate for the student to be successful in the core instruction (time: 1:30).

David Allsopp, PhD

Assistant Dean for Education and Partnerships

University of South Florida

Transcript: David Allsopp, PhD

One way to think about it is, if we know coming in that we have a subgroup of students coming in 9th grade who are going to need more-intensive levels of support in mathematics, we need to look at the minimum they’re going to need in order to graduate and how does that relate to their goals after high school? Is their goal to go to college? Is their goal to start a career? Then, in terms of looking at the four years, where might they best take the courses in mathematics that they will need? If they’re in a state where they have to have Algebra and Algebra 2 to graduate then where might we have kids taking those courses? Now, the second piece is how do you construct supplemental instruction? And is that a course? Many high schools conceptualize it as they’ve got to take a course in remedial math, and then they get to take algebra. But what we oftentimes see is that that remedial course really isn’t what that student needs in terms of being successful in Algebra 1 or being successful in Algebra 2. It might make sense to think about, if we’re going to engage students in the core content, how might we engage students in that course content while at the same time using time to provide more supplemental support?

To make certain that the intervention can be correctly tailored to meet specific learning needs, students should be homogeneously grouped according to whatever their area of difficulty happens to be. For example, students who struggle with addition problems that involve regrouping should be placed together, as should students who have difficulty with fractions. To meet the needs of all of these students, schools can purchase a variety of supplemental programs to use for Tier 2 intervention.

Center for Data-Driven Reform in Education (Johns Hopkins University)

Center on Instruction

RMC Research Corporation

Doing What Works

U.S. Department of Education

National Center on Intensive Intervention

American Institutes for Research

What Works Clearinghouse

U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Services

Tier 3: Intensive, Individualized Intervention

A small percentage of students who do not respond to Tier 2 intervention—approximately 5% of all students—will require even more intensive, individualized intervention. In the case of elementary students, intervention should be provided in small groups of 1–3 students for at least 20 minutes each day, whereas middle and high school students should receive intervention in small groups of 1–5 students for an entire class period. Instruction at this level is individualized based on the student’s needs. To individualize instruction, teachers can begin with the standard protocol used at Tier 2 and adapt it by making quantitative changes (e.g., changing the frequency of intervention, reducing group size). If the progress monitoring data indicate that the student is not responding, teachers can make increasingly intensive changes to the intervention by making quantitative or qualitative changes—such as those listed in the table below in order of increasing intensity—or using a combination of these changes.

| Change | Definition | |

| Changing the dosage or time | This means changing the:

|

|

| Change the learning environment | Teachers can change the learning environment by:

|

|

| Combine cognitive processing strategies with academic learning | Teachers need to incorporate cognitive processing strategies to address deficits in:

|

|

| Modify delivery of instruction | This can be accomplished by altering:

|

When delivered through the general education program, this instruction is typically offered by an individual who specializes in providing and designing individualized interventions. Alternatively, intensive, individualized intervention may be provided through special education services.

For Your Information

To qualify for special education services, students must meet certain criteria: 1) The student must have a disability, and 2) that disability must significantly affect his or her educational performance. Click here to learn more detailed information about RTI and the learning disability identification process.

RTI and the learning disability identification process

The RTI approach provides educators with a wealth of information about a student’s academic performance under increasingly intensive levels of instructional support. These data can be used as part of the process to determine whether a student has a learning disability and is eligible for special education services. The eligibility process consists of three basic steps:

- Referral

- Evaluation

- Determination of eligibility for special education

Referral

When a student does not respond adequately to supplemental instruction (i.e, Tier 2), school personnel might refer him for special education services. School personnel should meet with parents to review the student’s performance (e.g., progress monitoring data, work samples) to decide whether an evaluation for special education services is warranted.

Evaluation

The purpose of the evaluation is to rule out other possible factors that could account for the student’s poor mathematics performance, and, in turn, to indicate whether the student does in fact have a learning disability (LD). Factors to rule out include:

- A lack of appropriate math instruction

- Vision or hearing loss

- A low level of English proficiency

- An environmental or cultural disadvantage

- Low motivation

- Situational trauma (e.g., the death of a parent)

Ruling out these factors will require school personnel to make use of multiple sources of information, including school records, parental reports, and vision and hearing screenings. The existence of other disabilities—intellectual and developmental disabilities, visual impairment, hearing impairment, or emotional or behavioral disorder, among them—also needs to be ruled out as an explanation for the student’s poor mathematics performance. The assessments described below can be used to rule out such factors.

| Assessment | Purpose |

|

To eliminate intellectual and developmental disabilities as a cause of learning problems |

|

To eliminate speech or language impairments as a cause of learning problems |

|

To eliminate an emotional or behavioral disorder as a cause for academic failure |

Though they often begin by administering the assessments noted in the table above, the IEP team can request additional assessments to gain further information. Because the student’s progress monitoring data can serve as a measure of achievement, an achievement test is often not included in the evaluation. However, the specific measures required as part of this evaluation vary by state.

Determination of Eligibility for Special Education

Once the evaluation process is complete, the IEP team and the parents meet to review its results. If the team determines that the student meets the criteria established by the state for a learning disability, the student will receive more intensive, individualized intervention (i.e., Tier 3). Before this intervention can begin, however, an individualized education program (IEP) must be developed to address the student’s learning needs.

For Your Information

The formal process for referring a student for an evaluation and determining whether she meets the criteria for special education services requires school personnel to communicate with parents in order to:

- Request referral to evaluate the student for special education services (can be initiated by parent or school personnel)

- Provide written prior notice of the action the school is taking or refusing to take (e.g., evaluating or determining that there is not enough evidence to proceed)

- Inform parents of their procedural safeguards and their legal rights and protections under IDEA

- Invite parents to participate in the IEP planning process

For more information on the special education process, view the IRIS Module:

(Close this panel)

To learn more about intensifying instruction at Tier 3, view the IRIS Module:

Comparison of Instruction at Each Tier

The table below provides a side-by-side comparison of the features of instruction at each level of support.

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | |

| Who receives instruction? |

|

|

|

| Who provides instruction? |

|

|

|

| How is instruction delivered? |

|

|

|

| How long is the instruction provided? |

|

|

|

Note: The length of the instructional period may be dependent on the instructional program being implemented.