What is RTI for mathematics?

Page 4: Instruction

Effective instruction is a cornerstone of the RTI framework. As we discussed earlier, many but not all students who receive high-quality core instruction will succeed in the general education classroom. When teachers implement high-quality instruction at the primary level, inadequate instruction can be ruled out as a reason for students’ poor mathematics performance. Students who do not respond to this instruction should receive more intensive supports. Read on to find out more about high-quality instruction and how instruction is intensified at each of the three tiers of support.

Effective instruction is a cornerstone of the RTI framework. As we discussed earlier, many but not all students who receive high-quality core instruction will succeed in the general education classroom. When teachers implement high-quality instruction at the primary level, inadequate instruction can be ruled out as a reason for students’ poor mathematics performance. Students who do not respond to this instruction should receive more intensive supports. Read on to find out more about high-quality instruction and how instruction is intensified at each of the three tiers of support.

High-Quality Instruction

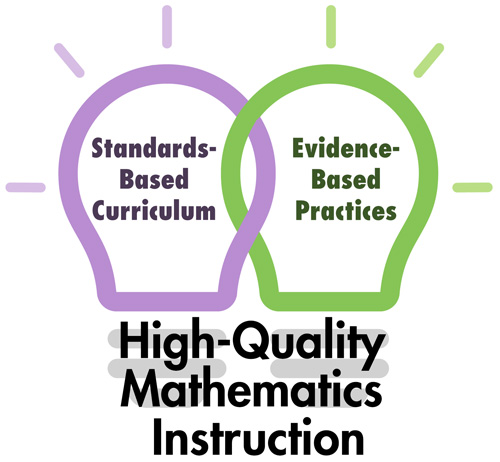

A key feature of RTI mathematics is high-quality instruction. High-quality mathematics instruction involves the combined implementation of:

Standards-based curriculum: The content and skills believed to be important for students to learn. Many states have adopted the Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSSM), which are composed of Mathematical Practices and grade-level standards. Additionally, the CCSSM:

- Build upon the strengths of current state standards

- Are informed by instructional practices used in other top-performing countries, so that all students are prepared to succeed in our global economy and society

- Are evidence-based

- Are aligned with college and work expectations

- Are clear, comprehensible, and consistent

- Embrace rigorous content and require the application of knowledge through higher-order skills

- Encourage the use of real-world problems

Evidence-based practices (EBPs): Strategies or practices proven through research to be effective for teaching mathematical concepts and procedures. The use of EBPs is mandated by the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) and the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). These federal laws require teachers to use, to the greatest extent possible, academic and behavioral practices and programs grounded in scientifically based research. Beyond the issue of legal obligation, however, is the fact that EBPs significantly increase the prospects of student achievement and learning. Among the benefits of using EBPs:

- Increased likelihood of positive student mathematics outcomes

- Increased accountability because there are data to back up the selection of a practice or program, which in turn facilitates support from administrators, parents, and others

- Less wasted time and fewer wasted resources because educators start off with an effective practice or program rather than attempting to select one through trial and error

- Increased likelihood of being responsive to learners’ needs

- Higher probability of convincing students to try a practice or program because there is evidence that it works

For Your Information

To implement high-quality instruction, teachers need to create a classroom environment conducive to learning. They can accomplish this by establishing a comprehensive behavior management plan that clearly outlines rules and procedures. They should hold high expectations for all students and use a range of instructional strategies and supports. Further, teachers are more likely to create successful learning experiences when they consider factors related to working with diverse students, such as:

- Cultural diversity: Instruction might be confusing to students if their cultural experiences or background knowledge are different from or inconsistent with those of their teacher.

- Linguistic diversity: Mastering academic content might be difficult for students who are not proficient in English.

- Students with exceptionalities: In the event that a disability affects a student’s learning, the teacher might need to make instructional adjustments to help that student to succeed. Similarly, gifted students might require different instructional opportunities like enrichment activities or accelerated learning.

- Socioeconomic diversity: Students might not have access to additional educational resources and supports outside of school.

Increasingly Intensive Levels of Support

All students receive core instruction in the general education classroom, also referred to as Tier 1. Those who do not respond adequately to this instruction receive supplemental support at Tier 2. The small percentage of students who continue to struggle after receiving supplemental support might require more intensive, individualized support at Tier 3.

Tier 1: Core Instruction

Instruction at the primary level, or Tier 1, refers to the high-quality core mathematics instruction (described above) that all students receive in the general education classroom for 45–90 minutes each day. This might be provided as whole-group instruction or through the use of flexible grouping strategies, for instance cooperative learning groups, paired instruction, or independent practice. A few of the evidence-based strategies that can be used to teach mathematics at this level of support can be found in the box below.

| Evidence-Based Practice | Definition |

| Explicit, systematic instruction | This strategy involves teaching a specific skill or concept in a highly structured and carefully sequenced manner. |

| Visual representations | This strategy involves creating an accurate representation of the mathematical quantities and relationships described in the problem, sometimes referred to as a schematic representation or schematic diagram. |

| Schema instruction | This strategy involves teaching students the underlying structure, or schema, of word problems and giving them a method for solving that problem type. |

| Metacognitive strategies | These strategies enable students to become aware of how they think when solving mathematics problems. More specifically, metacognitive strategies help students learn to plan, monitor, and modify their mathematical problem-solving approach. |

Approximately 80% of all students are expected to respond to Tier 1, or core instruction. Those who do not respond—as indicated by progress monitoring data—receive supplemental instruction at Tier 2.

More information about high-quality mathematics instruction and evidence-based practices that can be implemented at the primary level can be found in the IRIS Module:

Tier 2: Supplemental Intervention

In addition to core instruction, students not making adequate progress at Tier 1—approximately 15% of the class—receive supplemental instruction that aligns with that core instruction. Typically, in elementary schools a standard protocol is used to provide this additional instruction, which makes it easier to ensure accurate implementation or fidelity, assuming that school personnel receive adequate training and ongoing support. Likewise, in middle and high schools, a standard protocol might be used; however, many of these schools choose instead to implement a problem-solving approach.

Supplemental, or Tier 2, intervention is delivered either by the classroom general education teacher or another trained educational professional like a mathematics interventionist or mathematics coach. The specific details of this delivery varies for elementary and middle and high school.

| Group Size | Length of Intervention | |

| Elementary | 3–5 students |

|

| Middle and High School | Up to 15 students |

|

Brad Witzel discusses the importance of not ending an intervention too soon as well as of providing intervention that meets the needs of individual students (time: 1:27).

Brad Witzel, PhD

Professor of Special Education

Winthrop University

For Your Information

Because scheduling at the middle and high school levels is complex, the RTI team should carefully consider how to provide supplemental instruction in a way that makes sense given their school’s resources. Among the issues the team might wish to consider:

- When to provide supplemental support: Instead of an elective, during a free time, before or after school, within the core instruction class.

- How to create additional time for supplemental support: Shaving five minutes off of each period, reducing transition times between classes.

- How students will earn credits: Will they receive credits for supplemental support classes, and, if so, how many? Will they be able to accrue enough credits to graduate on time?

For students who require additional instructional support, David Allsopp suggests considering the students’ needs and being planful. By doing so, school personnel can better ensure that students get the support they need while at the same time taking required courses. He also discusses making sure that the supplemental intervention is appropriate and adequate for the student to be successful in the core instruction (time: 1:30).

David Allsopp, PhD

Assistant Dean for Education and Partnerships

University of South Florida

To make certain that the intervention can be correctly tailored to meet specific learning needs, students should be homogeneously grouped according to whatever their area of difficulty happens to be. For example, students who struggle with addition problems that involve regrouping should be placed together, as should students who have difficulty with fractions. To meet the needs of all of these students, schools can purchase a variety of supplemental programs to use for Tier 2 intervention.

Center for Data-Driven Reform in Education (Johns Hopkins University)

Center on Instruction

RMC Research Corporation

Doing What Works

U.S. Department of Education

Evidence-Based Intervention Network

University of Missouri

National Center on Intensive Intervention

American Institutes for Research

Promising Practices Network

RAND Corporation

What Works Clearinghouse

U.S. Department of Education Institute of Education Services

Tier 3: Intensive, Individualized Intervention

A small percentage of students who do not respond to Tier 2 intervention—approximately 5% of all students—will require even more intensive, individualized intervention. In the case of elementary students, intervention should be provided in small groups of 1–3 students for at least 20 minutes each day, whereas middle and high school students should receive intervention in small groups of 1–5 students for an entire class period. Instruction at this level is individualized based on the student’s needs. To individualize instruction, teachers can begin with the standard protocol used at Tier 2 and adapt it by making quantitative changes (e.g., changing the frequency of intervention, reducing group size). If the progress monitoring data indicate that the student is not responding, teachers can make increasingly intensive changes to the intervention by making quantitative or qualitative changes—such as those listed in the table below in order of increasing intensity—or using a combination of these changes.

| Change | Definition | |

| Changing the dosage or time | This means changing the:

|

|

| Change the learning environment | Teachers can change the learning environment by:

|

|

| Combine cognitive processing strategies with academic learning | Teachers need to incorporate cognitive processing strategies to address deficits in:

|

|

| Modify delivery of instruction | This can be accomplished by altering:

|

When delivered through the general education program, this instruction is typically offered by an individual who specializes in providing and designing individualized interventions. Alternatively, intensive, individualized intervention may be provided through special education services.

For Your Information

To qualify for special education services, students must meet certain criteria: 1) The student must have a disability, and 2) that disability must significantly affect his or her educational performance. Click here to learn more detailed information about RTI and the learning disability identification process.

To learn more about intensifying instruction at Tier 3, view the IRIS Module:

Comparison of Instruction at Each Tier

The table below provides a side-by-side comparison of the features of instruction at each level of support.

| Tier 1 | Tier 2 | Tier 3 | |

| Who receives instruction? |

|

|

|

| Who provides instruction? |

|

|

|

| How is instruction delivered? |

|

|

|

| How long is the instruction provided? |

|

|

|

Note: The length of the instructional period may be dependent on the instructional program being implemented.