How can educators recognize and intervene when student behavior is escalating?

Page 2: Acting-Out Cycle

When they are confronted by challenging behaviors such as yelling, swearing, or fighting, teachers often remark that “This behavior just came out of nowhere!” And though this might seem to be the case, there are typically warning signs that preceded the behavior. To be fair, these signs can be easily overlooked in a busy classroom full of students. However, as teachers learn more about each student, they can become aware of things that are likely to trigger a student’s challenging behavior. In fact, most students who consistently exhibit these types of behaviors typically progress through a seven-phase process known as the acting-out cycle, as described in the table below.

When they are confronted by challenging behaviors such as yelling, swearing, or fighting, teachers often remark that “This behavior just came out of nowhere!” And though this might seem to be the case, there are typically warning signs that preceded the behavior. To be fair, these signs can be easily overlooked in a busy classroom full of students. However, as teachers learn more about each student, they can become aware of things that are likely to trigger a student’s challenging behavior. In fact, most students who consistently exhibit these types of behaviors typically progress through a seven-phase process known as the acting-out cycle, as described in the table below.

| Acting-Out Cycle | |

| Phase | Description |

| Calm Phase | Student behavior is characterized as goal-directed, compliant, cooperative, and academically engaged. The student is responsive to teacher praise and willing to cooperate with peers. |

| Trigger Phase | Student misbehavior occurs in response to an event either within or beyond the school day. When a student encounters a trigger, he may become restless, frustrated, or anxious. |

| Agitation Phase | The student can engage in a variety of off-task behaviors. Some students might dart their eyes, tap their fingers, or start and stop their activities. Others might disengage or stare off into space. |

| Acceleration Phase | The student’s challenging behavior intensifies and is often directed at the teacher. It’s at this stage that a teacher often first recognizes that a problem is occurring. |

| Peak Phase | The student’s behavior is clearly out of control (e.g., yelling at the teacher, hitting others, destroying property) and may create an unsafe classroom environment. |

| De-escalation Phase | The student is less agitated and may be confused or disoriented. Many students will withdraw, deny responsibility, attempt to blame others, or try to reconcile with those they harmed. |

| Recovery Phase | The student is generally subdued and may wish to avoid talking about the Peak incident. The student returns to the Calm Phase. |

Click on the video below to learn about the seven phases of the acting-out cycle (time: 2:25).

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

In general, we encourage all faculty and staff to learn about the acting-out cycle. You can think of this as a seven-step cycle that begins with a calm stage. And although (laugh) not every student comes to school calm every day, we think at some point in their life they have experienced some type of calm. And then something sets that student off and that can be thought of as a trigger. And sometimes those are school-based things like assemblies or schedule change, or could it be a difficult assignment or something like that. And some of those triggers can also be non-school based. It could be coming to school tired or hungry, or having not slept well the night before, or having had an argument with their parents or a conflict with a peer. And then if those triggers aren’t noticed and responded to, then that behavior can shift from signs of agitation and then really ramp up to signs of acceleration. And it’s during that acceleration phase, the behavior can really ramp up. And that’s when it’s easy for teachers to begin to notice these concerns when those behaviors are escalating. And for some students, this acceleration phase can last for several minutes, and then left unchecked, it can continue to escalate if it’s not nipped in the bud right there. And eventually it creates these peak behaviors when behavior is very, very out of control. And that’s when we start to see things like verbal and physical aggression in the classroom in a way that sometimes results in property destruction or harm to others. And then following that, there is a de-escalation and then eventually a recovery phase. So, you’re going up and then you’re coming back down. The good news is that it is possible to interrupt this acting-out cycle much earlier in the chain, long before the student reaches peak behavior, which can be frightening for teachers and students alike, and not just the student experiencing the challenging behavior, but others in the classroom.

In addition, we’ve learned that timing is everything. Meaning that it’s important for adults to understand when low intensity support, such as reminding students of expected behaviors or providing praise when the student meets desired behaviors and even offering choices can be introduced efficiently and effectively, and also knowing when they should not be used. Because used at the wrong time, it could actually have a counterproductive outcome for the student.

Credit

The acting-out cycle diagram is adapted from Colvin, G. (2004). Managing the cycle of acting-out behavior of the classroom. Eugene, OR: Behavior Associates.

Recall from the Challenge that Mr. Santini has two students who exhibit challenging behaviors—Nora and Kai. The first video takes a closer look at what Nora’s behavior looks like within the context of the acting-out cycle (time: 4:25).

Transcript: Acting Out Cycle – Nora

Teacher: All right friends, you’ve had time to check your homework. What questions do you have?

Teacher: Yes, Jordan.

Jordan: Can you show me how you solved number three?

Teacher: Number three, sure. Let see, we have 40 times three. Remember, we always start multiplying with the digit in the ones place. So we have three times zero. What is three times zero?

Jordan: Three times zero equals zero.

Teacher: Yes. Three times zero equals zero. And where do we write the zero in our answer?

Jordan: In the ones place.

Teacher: Nice. Three times zero equals zero. Next, we need to multiply …

[Nora sighs heavily in frustration, rolls her eyes, and crosses her arms.]

Teacher: … three times the digit in the tens place which is four. What do we do next?

[Nora sighs heavily in frustration, makes noise expelling through her mouth.]

Jordan: Multiply three times four, which is 12.

Teacher: Nice, three times four is 12, and there we go.

Teacher: Yes, Colin?

Colin: Can you look at mine?

Teacher: Yes, I will be right there.

[Nora sighs.]

Teacher: [To Nora] You know what, I don’t know why you’re being so rude today. What’s going on?

Nora: This is a waste of my time!

Teacher: Excuse me. You need to speak to me with respect.

[Nora sighs loudly.]

Teacher: Friends any other questions before we move on?

Nora: I said, this is a waste of my time!

Teacher: That’s an inappropriate way to speak to the teacher. If you don’t get your tone under control, there will be consequences.

Teacher: [To class] Last call for questions? Otherwise, we’re going to get started on today’s warm-up.

Nora: [pushes over chair] You’re so annoying! I hate this class!

Teacher: [To another student] Take this to Ms. Chen, please.

Teacher: [To class] Class, let’s line up at the door and go next door to Ms. Chen’s just like we practiced.

Teacher: Nora, I see you’re feeling upset. Do you want to go to the peace corner and do some deep breathing? OK. Good call. Thank you.

Teacher: Hey Nora, how you feeling?

Nora: A little better.

Teacher: Oh, yeah? Well, if you’re ready, you can go work on the math review worksheet and I’ll bring the class back.

Nora: OK.

Teacher: All right, cool. Thank you. Here you go. Nice job.

Nora: I’m finished.

Teacher: Great Nora. Thanks for finishing your math activity. I’m going to give you this debrief form, and you can use this to tell me about what happened earlier, OK?

Just let me know when you’re done.

Nora: I’m done.

Teacher: Great! Thanks for completing the debriefing form, Nora.

Hey, let’s talk through what happened earlier. Can we start with your reflection?

Nora: OK.

Teacher: Great! I see that you were frustrated by having to wait to do your math work. It was hard to hear other students ask questions that you already knew the answers to? I can totally understand that, but what did you do?

Nora: I talked out. Then I yelled and I knocked over my chair.

Teacher: I saw that too. How did that work out? How do you feel about the result?

Nora: I feel embarrassed, and I wish I hadn’t done it.

Teacher: I know. What do you think about what you could do the next time? Give me some ideas, I can help you.

Nora: Maybe I could ask to work ahead?

Teacher: Nice. That’s a super idea. How about I find some challenging activities for you to keep at your desk just for times like this?

Nora: OK.

Teacher: Also remember you always have the option to go to the peace corner and use the activities over there.

Nora: OK.

Teacher: Great. Now, here’s the thing: whenever a student shows any unsafe behavior in the classroom, the teacher needs to call home and write an office referral. OK, I just want to make sure you’re aware of that so it’s not a surprise. You have any questions about that?

Nora: No. I get it.

Teacher: Great! Before we move on, is there anything else you need or want me to know? Anything thing else that I could help make you wait better the next time?

Nora: I don’t know. I’m always waiting for adults to help other kids so they can help me.

Teacher: That’s right. You have a baby sister.

Nora: Yeah. She gets all the attention.

Teacher: I’m sorry to hear that. That must be pretty hard. If you ever want to talk about that we totally can.

Nora: OK.

Teacher: How are you feeling now?

Nora: I feel a little bit embarrassed, but I’m feeling a lot better.

Teacher: That’s totally understandable. I’m glad you’re feeling better, and I just want you to know, I’m very glad to have you in my class.

Nora: Thank you.

(Close this panel)

The second video illustrates Kai’s behavior during the acting-out cycle (time: 4:57).

Transcript: Acting Out Cycle – Kai

Teacher: Alrighty friends, we are going to read a passage about the landmarks in Tennessee. Would someone like to volunteer to pass out the readings?

Teacher: Thank you, Kayla.

Teacher: Colin, nice job sitting quietly.

Teacher: Kai, excellent job showing me you’re ready for reading by sitting quietly.

Kai: Thanks.

Teacher: Okay, so today we are going to do a popcorn activity with fun facts you learned about Tennessee and if you want, you can read them right from your book.

Teacher: Okay, let’s see. Diamond, could you start us off?

Diamond: Sure. Tennessee touches eight other states: Missouri, Kentucky, Virginia, North Caro-N-North Carolina, Arkansas, Georgia, Mississippi, and Alabama. Popcorn, Haley.

Haley: Tennessee is tied with Missouri for the state with the most borders. Popcorn, Riley.

Kai: Ugh [puts head down, taps pencil on desk]

Riley: Tennessee is famous for its music, hot chicken, and rolling hills. It’s called “The Volunteer State.” Popcorn, Kai.

Kai: Uh. That’s the one I was gonna say. Umm… Tennessee is pretty moun-mount-uhh-a [puts head on desk].

Teacher: Kai, that word is mountainous, and please keep your head up and keep trying your best.

Kai: Uhh I’m done with this!

Teacher: Excuse me, sir, that’s not how we talk to each other.

[Kai gets up out of his seat and pushes the papers off his desk.]

Kai: Leave me alone! [runs out of classroom]

Teacher: Class, please continue with your reading [looks out the classroom door].

Teacher: [[picks up the classroom phone] Hi. Kai is headed towards the cafeteria. Thank you. [hangs up phone]

[SOMETIME LATER]

Teacher: Hi.

Principal Sanders: Kai is back, and he’s calmed down a little bit.

Teacher: Great. Thank you. Can you take over the reading activity for me?

Principal Sanders: Yes.

Teacher: Sure. [hands Principal Sanders the reading activity]

Teacher: Class, Principal Sanders is going to take over the reading activity, and when you’re done, you can work on your comprehension section.

Teacher: [meets Kai in classroom doorway] Kai, I’m so glad you’re back. This might be a good time to go straight to the Peace Corner. Does that sound cool?

Kai: Okay.

Teacher: Right on. Go ahead. Relax.

[Kai reenters the classroom.]

[10 MINUTES LATER]

Teacher: Hey, Kai. Are you good?

Kai: Yea, I’m good.

Teacher: Awesome, bud. If you’re ready, I have an activity for you to complete at your desk.

Kai: Okay.

Teacher: Okay, cool. Why don’t you pick up your things and get settled and then I’ll give you the directions.

[Kai picks up his things from the floor and sits in his desk.]

Teacher: Great. Thanks so much for picking that up, Kai. [puts worksheet on Kai’s desk] This activity is about the story we read yesterday, so these are pictures of events in the story, and your job is to put them in order.

Kai: Got it.

Teacher: Cool, and just let me know if you have any questions.

[5 MINUTES LATER]

Teacher: Hey, Kai. Do you think you’re ready to give some thought to what happened earlier?

Kai: Yea.

Teacher: Great. [places debriefing behavior form on Kai’s desk] You can use this form to talk about what happened, why, and what we could maybe do differently next time. Okay, and you can let me know when you’re done.

Kai: Okay.

Teacher: Any questions, just let me know.

[5 MINUTES LATER]

Teacher: Hey, Kai. Let’s revisit what happened earlier. Okay?

Kai: Sure.

Teacher: I’m going to use this form to guide our conversation. [touches debriefing behavior form]

Kai: Sure.

Teacher: [picks up debriefing behavior form] Cool. I saw you get upset and run out of the classroom. Umm can you tell me about what happened from your perspective?

Kai: I knew I was gonna have to have a turn. I don’t know how to read all the words, and everyone else knows it.

Teacher: I see. So, you were already upset before you even started and then when it was your turn, you ran into a tough word. What did you do to deal with all of that?

Kai: I don’t know. I got angry and ran away.

Teacher: Yea. How did doing that work out for you?

Kai: Not good. Now I look bad in all kinds of ways.

Teacher: I can totally understand you feel that way, but I think your classmates like you and appreciate you and you don’t have anything to worry about. But is there something else you could try next time that might work better?

Kai: Can I skip my turn?

Teacher: That’s a great idea. Then next time we can just agree if you come to a word that you don’t know, just popcorn to someone else. Okay?

Kai: Okay.

Teacher: You can also always ask for help. There’s no shame in that. Umm, I’ll also try to give you some time to look at the passages in advance if you want. Okay? Maybe we could practice the first sentence and have you start the popcorn activity the next few times.

Kai: I would like that.

Teacher: Umm. I want you to try writing down these strategies. You can write “Ask for teacher’s help and then keep going from there. Okay. [places debriefing behavior form back in front of Kai]

Kai: Okay.

Teacher: You can let me know if you need any help.

Kai: I’m done. [hands debriefing behavior form to teacher]

Teacher: Alright, Kai. Nice job writing down those strategies we identified. One more thing we need to talk about. Any time a student shows any unsafe behavior in the classroom, like leaving the room without permission, the teacher needs to call home and write an office referral. I just want to make sure you’re aware of that so it’s not a surprise. Do you have any questions about that?

Kai: No, but my mom is gonna be mad.

Teacher: I’ll do my best to make sure your mom understands that this is all part of the process and that you’re learning how to get your needs met. Okay? So, no worries about that.

Kai: Thanks.

Teacher: Cool. And what do you think about making some extra time to practice reading?

Kai: I’d like that.

Teacher: That sounds great. Umm, I’ll talk to your mom about that too, and then really thanks so much for having this conversation. I think you did a great job, and I’m really glad you’re in my class.

Kai: Thanks, Mr. S.

(Close this panel)

In this interview, Kathleen Lane offers more information on each phase of the acting-out cycle (time: 1:55).

Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

Professor, Department of Special Education

Associate Vice Chancellor for Research

University of Kansas

Transcript: Kathleen Lane, PhD, BCBA-D

The acting-out cycle is a really wonderful theoretical illustration about how problem behaviors occur. A lot of times teachers will say, “The student just started screaming out of control” or “The student just blatantly refused to do their work” or “just stormed out of the room for no apparent reason.” And what they’ve shown through this acting-out cycle is that behavior actually does occur in a chain. And what most teachers are noticing are either peak behaviors where students are completely out of control, either throwing a chair or using profanity, or being very verbally or physically aggressive. Or sometimes there are actually earlier behaviors that could have been detected before that big acting-out behavior occurred. We can think of this as a precursor behavior. It’s basically important for every educator, those in the general education and special education communities, to be empowered with the knowledge that we can look for these signs of behavioral challenges that show up much earlier in the acting-out cycle, such as being off task, and respond to those smaller challenges before those little things become really big behaviors that can feel pronounced and out of control. And frankly, they’re difficult to manage. Ideally, every teacher could learn about respectful, effective ways to respond to challenging behaviors. That generally begins with showing empathy towards that student that is beginning to show some challenging behaviors. At the same time, they’re maintaining the flow of instruction to keep other students engaged. And then they acknowledge students who are meeting those expectations and provide very clear, kind redirects to teach those students that are struggling the expected behaviors for that moment, and then allowing those students who are struggling time and space to get back on track. And as soon as they do, then reinforcing them as soon as they engage in those expected behaviors.

To understand and prevent challenging behavior early in the acting-out cycle, teachers must first understand that every behavior is an attempt at communicating something. In many cases, challenging behaviors are an inappropriate way for a student to either:

- Obtain something desired (e.g., attention, a tangible item, an activity)

- Avoid something not preferred (e.g., a difficult task, an activity, an interaction with a teacher or peer, an undesirable situation)

By understanding what a student’s behavior is communicating, a teacher can take steps to prevent or address the behavior before it escalates. Intervening early in the acting-out cycle allows the teacher to address the behavior while it is less serious and when students are more likely to respond to efforts at intervention. If teachers can prevent challenging behaviors from gaining momentum, they can stop more serious behaviors from occurring, and in turn support that student and maintain a positive, productive classroom environment.

Tiered Systems

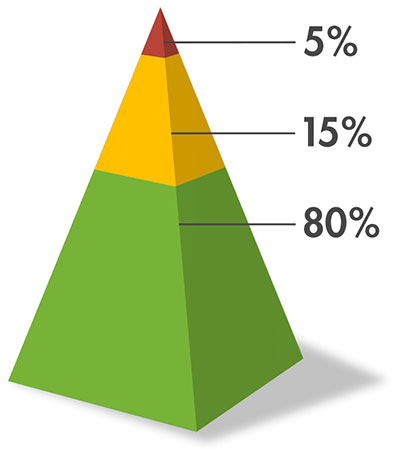

Many schools across the country are embracing a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) to prevent and respond to challenging behaviors. One such approach is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS). This framework provides the structure (broad practices and core principles) around which school-wide expectations are established, taught, and practiced. Within this tiered systems approach, educators identify and use evidence-based practices (EBPs) to improve academic and behavioral outcomes for all students. PBIS consists of three tiers of prevention—Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3—through which educators can provide a continuum of supports and services to promote appropriate behaviors and address challenging ones.

Many schools across the country are embracing a multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS) to prevent and respond to challenging behaviors. One such approach is Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS). This framework provides the structure (broad practices and core principles) around which school-wide expectations are established, taught, and practiced. Within this tiered systems approach, educators identify and use evidence-based practices (EBPs) to improve academic and behavioral outcomes for all students. PBIS consists of three tiers of prevention—Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3—through which educators can provide a continuum of supports and services to promote appropriate behaviors and address challenging ones.

multi-tiered system of supports (MTSS)

A preventive framework that integrates high-quality instruction, assessment (i.e., universal screening, progress monitoring), increasingly intensive and individualized levels of instructional or behavioral intervention, and data-based decision making to address the needs of all students, including struggling learners and students with disabilities. Two examples of MTSS are response to intervention (RTI) and Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS).

Positive Behavioral Interventions and Supports (PBIS)

A three-tiered framework (i.e., primary, secondary, tertiary) that provides a continuum of supports and services designed to promote appropriate behaviors and to prevent and address challenging behaviors.

evidence-based practice (EBP)

Any of a wide number of discrete skills, techniques, or strategies which have been demonstrated through experimental research or large-scale field studies to be effective. Not to be confused with an evidence-based program.

Also referred to as primary or universal prevention, Tier 1 consists of effective school-wide or classroom behavior management practices. Establishing classroom structure and teaching behavioral expectations to all students can prevent or minimize most challenging behaviors. To learn more about this, view the IRIS Modules:

Also referred to as targeted or secondary prevention, Tier 2 offers targeted supports to some students whose needs are not being met by Tier 1 supports. These include self-regulation strategies (e.g., self-monitoring) and check-in/ check-out. To learn more about self-regulation strategies, view the IRIS Module:

self-regulation strategy

Any of a number of instructional strategies designed to help students to select, monitor, and use learning strategies.

self-monitoring

Any of a number of instructional strategies designed to help students to select, monitor, and use learning strategies.

check-in/check-out (CICO)

Strategy designed to decrease chronic undesired behaviors. The student checks in at the beginning of the day or the class period with a designated adult and develops a behavior goal. Throughout the day, other adults indicate progress toward meeting the goal on a point card (sometimes referred to as a “behavior report card”). At the end of the day, the student meets again with the designated adult to review the student’s progress throughout the day and to tally earned points. The parent reviews and signs the card each day. Note: This strategy should not be used to address dangerous behavior.

Also referred to as tertiary intervention or intensive, individualized prevention, Tier 3 offers an individualized support plan to the few students whose needs are not met by Tier 2 supports. This might include a functional behavioral assessment (FBA) and a behavior intervention plan (BIP). To learn more about FBAs and BIPs, view the IRIS Module:

functional behavioral assessment

A behavioral evaluation technique that determines the exact nature of problem behaviors, the reasons why they occur, and under what conditions the likelihood of their occurrence is reduced.

behavior intervention plan

A set of strategies designed to address the function of a student’s behavior as a means through which to alter it; requires a functional behavioral assessment and an associated plan that describes individually determined procedures for both prevention and intervention.

In these interviews, Pamela Glenn and Janel Brown describe how tiered systems of support are implemented in their schools.

Transcript: Pamela Glenn

As a school, we do have a tiered behavior system and we do work with the PBIS system. We have the Tier 1, where everybody has the same level of instruction and the same level of behavior expectations. We have what we call SOAR. We’re Eagles. It’s being safe, being on-task, accepting of responsibility, and being respectful. That’s what S-O-A-R stands for. We all work on the same premise that we are striving to soar and be eagles because eagles were made to soar. Then at the Tier 2, you have those students that are not quite making it and go from like the 70, 80% down to the 20%. Then there’s the additional supports, and we have lesson plans in place to reteach the lessons for the behaviors that we’re seeing that are not being mastered. For example, if Johnny is not being safe in the classroom, it would be a moment to, “Okay, what’s going on, Johnny? We’re having this problem where everybody else is on-task and doing their work, and you’re running around. Talk to me and let’s see what’s going on. Maybe we need to put something in place for you.” And then we monitor that. At the Tier 3, it would be that 3 to 5% of students that need additional supports. Do they need an IEP? Do they have an IEP? Are we following their 504? And then honing in on what supports does the student need. Do we need to get the parents involved? And then that would be a specific behavior plan that we would put in place for that specific student. We have a lot of PBIS celebrations. Every quarter there is something that the students are working towards, be it ice cream party, a dance party, a field day. And then in between each quarter, there’s a mini celebration. It may be a T-shirt day or something that the students are working towards, and we promote that throughout the weeks leading up to. And I usually have a sticker chart, or they have a little card that they’re checking off. We all support each other, and everybody helps each other out so that they can participate in those celebrations.

Transcript: Janel Brown

We have MTSS, which is multi-tiered systems of support. There’s three levels. There’s Tier 1, which is the entire school. There’s Tier 2, which may be a select group of students. And then we have Tier 3, which is more one-on-one with students. And we also have PBIS, Positive Behavior Interventions and Supports. We have what we call here Eagle Bucks. If kids are adhering to the expectations in class, they’re on task. Whatever that teacher has posted in her classroom, if they’re doing that, she passes out Eagle Bucks. At one month, there’s a reward if you have a certain amount of Eagle Bucks. At the end of the nine weeks, there’s a big reward. Tier 2 will be those students who need maybe just a little support academically, emotionally, socially. They may go and see the guidance counselor for social emotional learning. And, they have their little group, and they talk about things that are going on or what they need help with. Here at my site, we had a program called Drumbeat. Once a week, we got together in one of the classrooms and every kid had a drum. So, the opening would be, Rumble if… So, every child got to make a statement, Rumble if… you ate breakfast this morning. So, all the kids would rumble the drum, and if they didn’t, that gave the leaders an opportunity. “Okay, so Susie, what happened that you didn’t get to eat breakfast this morning?” And it may be that Susie didn’t have anything at home to eat for breakfast. That gives us an idea. Okay, Susie may need help. And anything that was talked about within that class, stayed in the class. So they couldn’t go outside of the classroom, discuss anything that we talked about, because some students did share personal things and we didn’t want it shared about campus. Tier 3 is more the one-on-one. Over the years I’ve had plenty Tier 3 students. One-on-one would be like Check-in/Check-out. I’ll have to check in with them at breakfast time, lunch time, and before they went home and sometimes in between. It was just a constant check-in activity to make sure they were on track, to make sure they were on-task if they had any issues. Perhaps they needed to just come and talk for a minute. They could come, they were allowed to get a pass and they would come and just have conversation about something that was bothering them in the moment. And those students were some of our more severe behavior students. It would get them out of the classroom for a bit to even give the classroom teacher a break and for the students to get a break.

To learn about two models of tiered systems of support, visit the following centers.

Center on Positive Behavioral Interventions & Supports (PBIS)—As mentioned above, PBIS is a framework that provides foundational systems and identifies key practices of Tier 1, Tier 2, and Tier 3 to improve academic and behavioral outcomes.

The Comprehensive, Integrated Three-Tiered Model of Prevention (Ci3T) is an integrative model that incorporates academic and behavioral supports, with the addition of supports to address social and emotional well-being.

By working through this module, you’ll learn more about the different phases of the acting-out cycle. For each phase, you will be introduced to some strategies and tips that can help you address student behavior proactively, appropriately, and respectfully.